Ephemeron is a fleeting thing, such as printed items, on paper, doomed to be thrown away.

This was mostly true until an eccentric bunch – with the time and inclination – began choosing not to discard the stamps, labels and scraps ejected from the inky back-end of the industrial revolution.

But here and now, in an increasingly oversaturated matrix, does the definition hold up at all? Tracing a line from a 1990s boom in antique roadshows and guidebooks on collectables, through to the petabytes of printed tat – digitised and beamed from Discogs, Instagram and eBay pages – might lead you to this question: for something supposedly transitory, how come there’s all this old ephemera still knocking about?

The cluttered core of my hoarder’s psyche recoils. “What harm can it do?” I wheeze amongst the musty crates at the collector’s fair. “Besides, it’s print, right, the bedrock – the foundation of all knowledge? And these records – surely they’re not ephemera? Don’t their data-etched surfaces impress as something so much more? Aren’t they actually cultural artifacts?”

After the half-baked justification I take a few moments to willfully ignore the horror of millions of broken 78s, unspooled tapes, scratched LPs and compact discs buried deep in the world’s landfills. For now I’m home, above ground, with a mug of tea steaming. As the needle drops into the groove I reach for a record’s scuffed and sellotaped sleeve and begin looking and listening; lost in music, a fleeting thing.

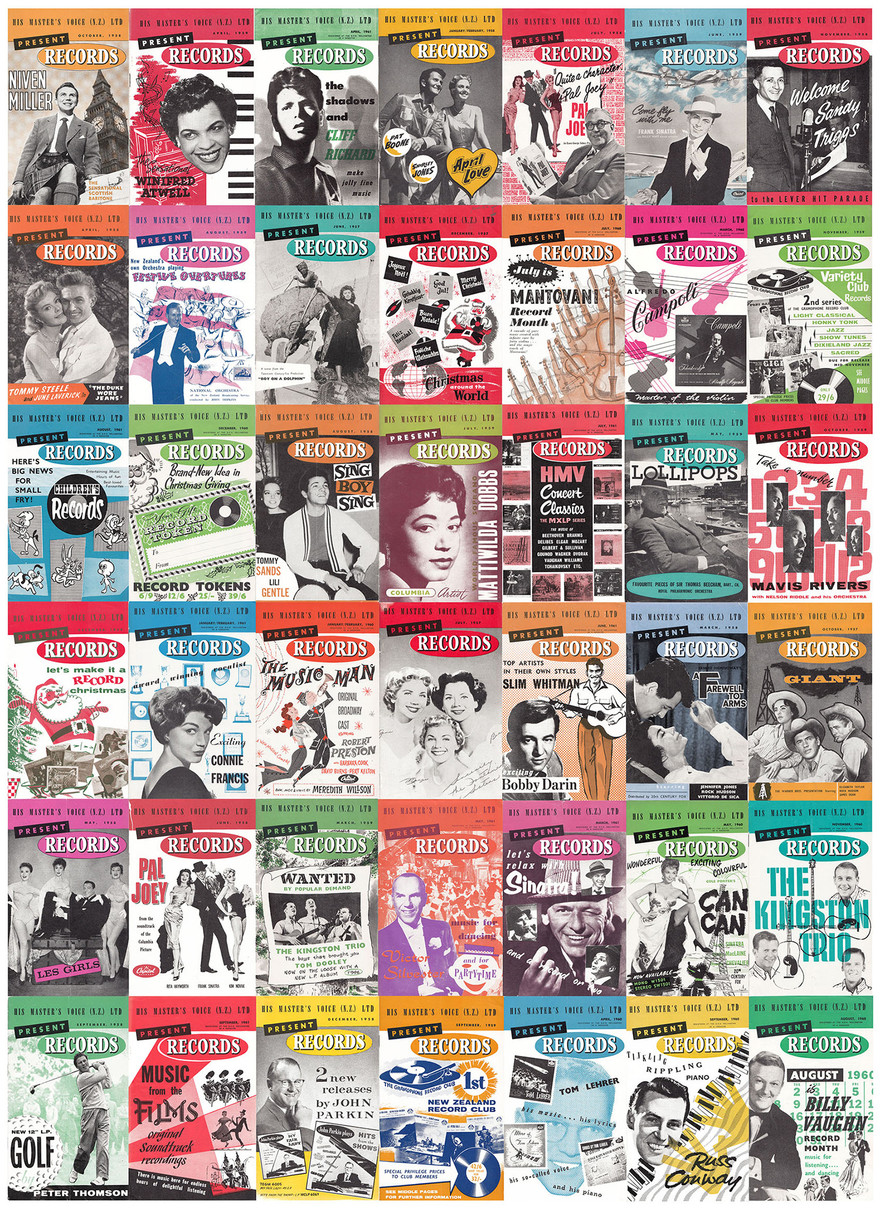

HMV Catalogue covers 1957-1961.

This stack of His Master’s Voice (N.Z.) Ltd Present Records magazines are a perfect example of ephemera. They’re printed in budget-conscious two-colour letterpress and at 5” x 8” (approx 13cm x 30cm) neat enough to fit an imperial US letter envelope

The monthly catalogue was mainly sold to retailers through subscription at sixpence a copy ($2.50 in 2021 money). They are basically lists of forthcoming record releases from HMV (NZ) and its associated labels; early in its history, HMV (NZ) Ltd distributed 80% of the world’s record labels. Upon receipt of the following months’ lists, previous issues would be redundant – a publication with inbuilt obsolescence.

The magazines are a delight to look at – their muted greens and dusty blues evocative of vintage motorcars in colours you never see now. As well as the itemised record releases there are also marvellously recherché advertisements for fridges and radiograms.

The series started in August 1956 and is nearly complete up to 1961. The years covered are New Zealand’s post-rock-pre-beat transition: a societal period full of twists and tumult.

For a long time the magazines lived in my cupboard. I’d flick through them occasionally, doing a double take when coming upon some esoteric jazz listing – “That was released in New Zealand?” – but imagined them being fairly common, the sort of periodicals filed in wooden boxes next to old postcards on second-hand bookshop counters.

It was only when I hauled them out during a spring clean and showed them to AudioCulture’s Chris Bourke and Simon Grigg that I began to understand they might actually fulfill one of ephemera’s most prestigious attributes: apparently, they’re quite rare.

What’s the story behind them? G.A. Tait, in an authorised history from the 1959 book Manufacturing In New Zealand, breathlessly detailed the rapid growth of HMV (NZ)’s post-war record production:

“The demand for discs also mushroomed as music lovers sought new records almost in vain. Licence-control of imported goods stopped them from getting the discs they wanted, and to overcome this problem a factory was established in Kilbirnie, Wellington, in March, 1949.” Phew!

But this was not quite as valiant as it appears. HMV (NZ) was a branch of a multinational company and it wanted to dominate the local market. In 1951 it showed its hand by attempting to stifle booming homegrown labels Tanza and Zodiac.

“Pistol-to-the-head-persuasion” claimed the Auckland Star as dealers’ supply lines of HMV-controlled imports were threatened should they dare stock the local labels. Luckily the commercial popularity of the maverick indies saw the big boys’ bluff called.

By 1954 HMV’s Kilbirnie factory was at capacity forcing the company to expand into a leased building in Lower Hutt. Workers were chivvied into double shifts to cope with the rocketing demand for the new fangled EP and LP microgroove formats.

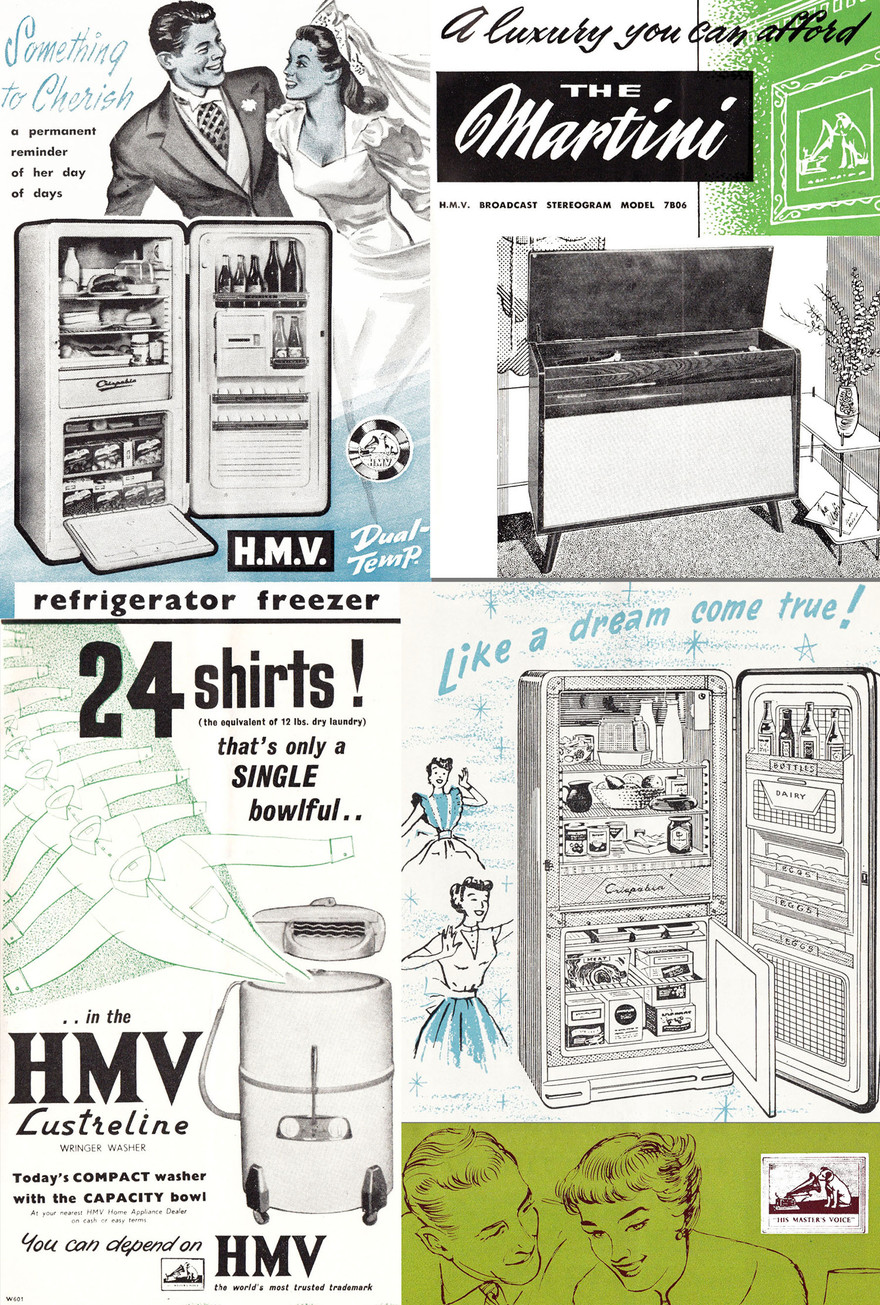

The company’s Present Records magazine was launched in August 1956 from a template set by head office in the UK. It differed from the British magazine however by featuring adverts for washing machines, fridges and radiograms – now being manufactured in increasing numbers on New Zealand soil. The company likely saw the publication as a useful tool to consolidate the marketing of both discs and home appliances, going to press shortly after the 1955 opening of a new South Island distribution centre in Christchurch.

HMV appliances: a fridge is “Something to cherish: a permanent reminder of her day of days.”

In an early example of brand synergy this was HMV (NZ) propagating the “design-for-living” ethos, a fantasy import from mid-century America where wasp-waisted housewives lived the populuxe dream via self-cleaning ovens and giant refrigerators. Meanwhile, in a haze of martinis and warm vacuum tubes, their husbands slumped in front of exotically veneered hi-fis, lulled by the dying embers of the Great American Songbook.

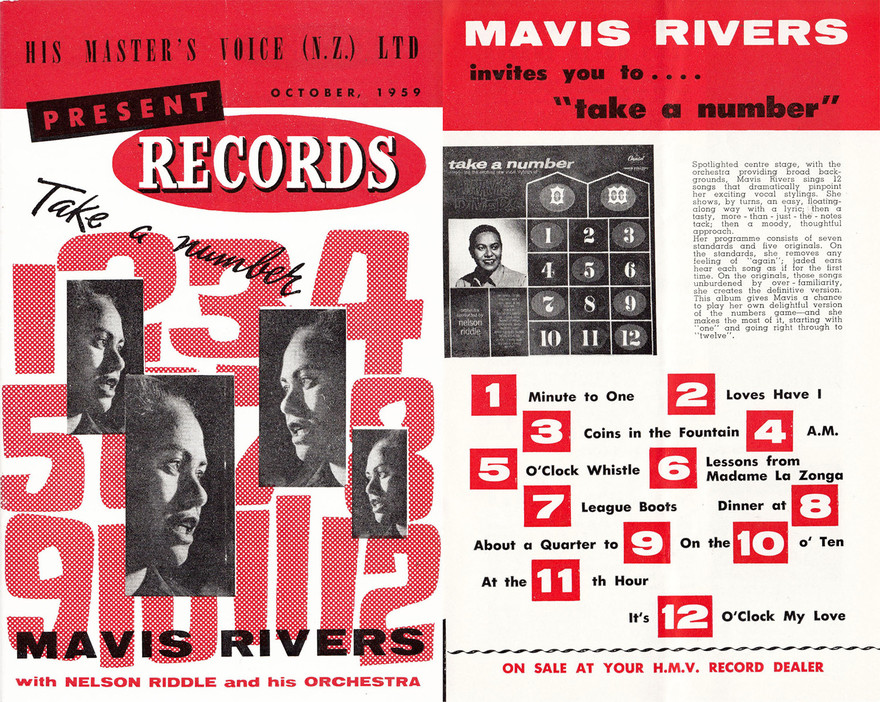

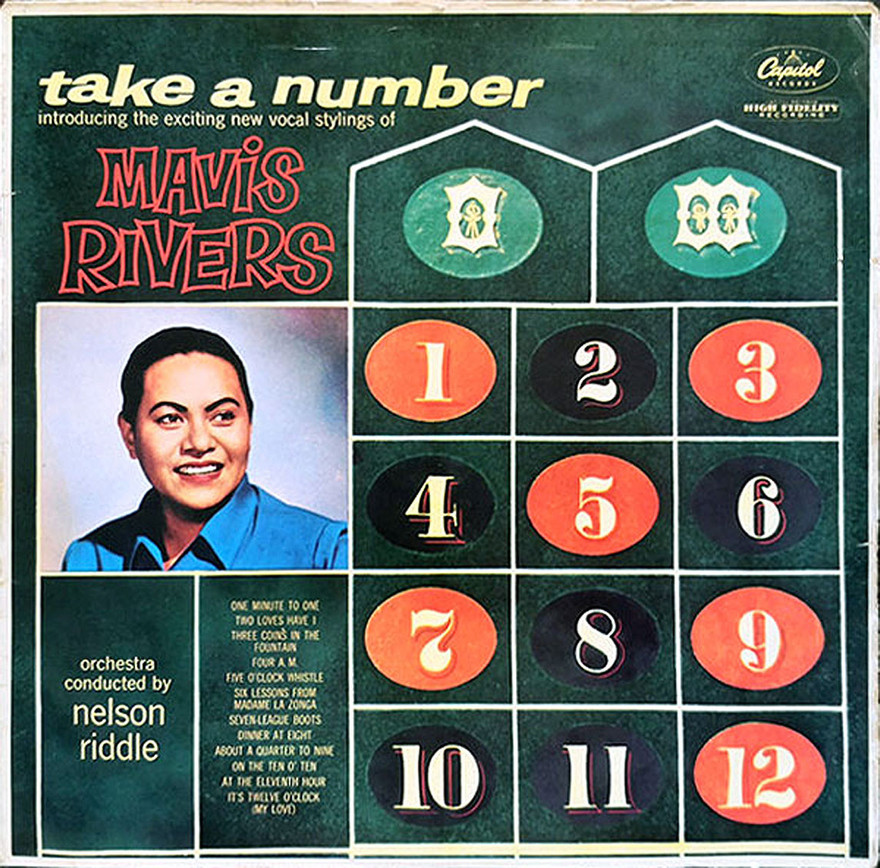

Possibly spinning on just such a hi-fi might have been the first LP from Samoan-born Kiwi nightclub star Mavis Rivers. Take A Number is featured on the October 1959 cover of Present Records magazine with a striking montage created expressly for the local readership.

Mavis Rivers.

Informed by the US Capitol LP’s back cover, the uncredited designer in HMV’s art department manages to create a more concise layout for the magazine than the busy, rather contrived original sleeve. The US Capitol artwork was already dark and this was only emphasised on the domestic pressing by being re-photographed and reprinted. Due to import restrictions HMV (NZ) was obliged to house all overseas recordings in sleeves produced from local film and plate, a clause the New Zealand Printing Union very much approved of.

Mavis Rivers - NZ edition of Take A Number

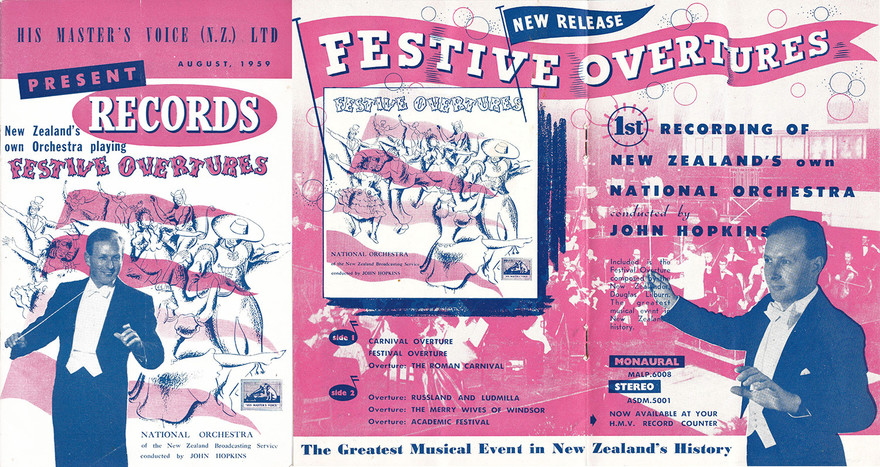

The less-is-more qualities of the magazine’s designs are impressive. The two-colour printing process – sometimes known as spot colour – used black plus one other colour for the letterpress’s ink trays. Occasionally the designers plumped for two spot colours – red and green ink for a Christmas special or the royal blue and pink combination for the August 1959 issue promoting the National Orchestra of the New Zealand Broadcasting Service’s recording of Festive Overtures.

August 1959 cover and double-page-spread composite.

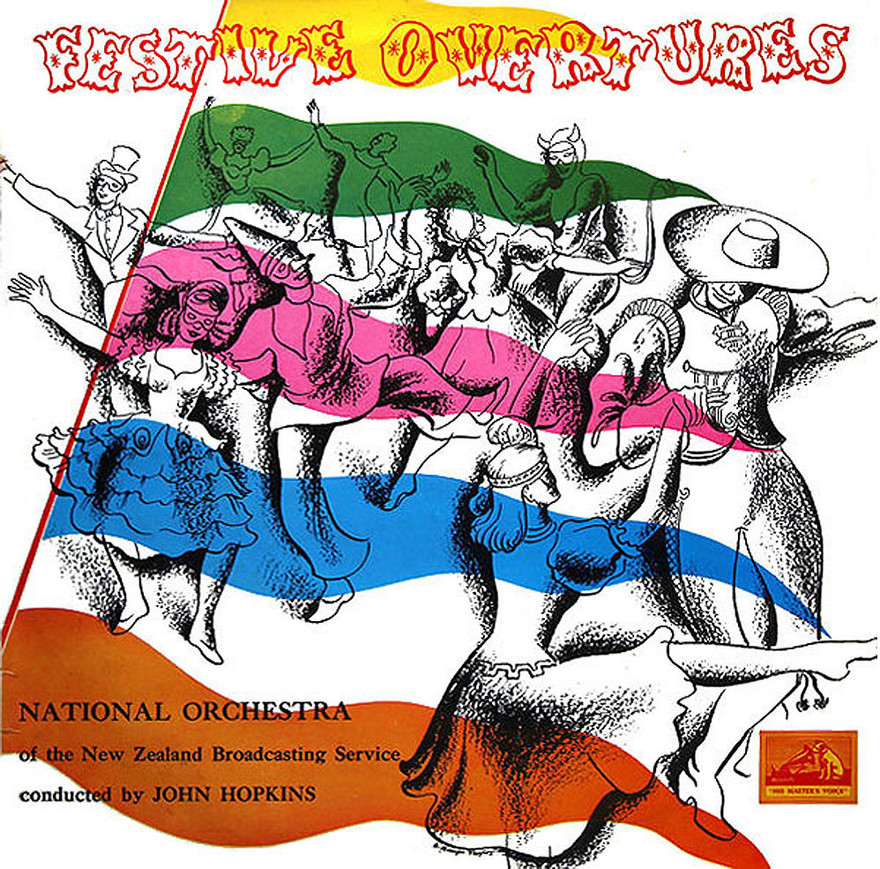

There’s some splendid work here both in design and printing. As with the magazine’s Mavis Rivers layout the necessary restriction of working with just two colours – as opposed to the four-colour offset litho process used on the album cover – produces, in my opinion, a more cogent result. The LP’s somewhat garish banners are now converted to a 20-30% halftone pink with the formerly black line work rendered in 100% blue.

Festive Overtures Cover

Printing work for the magazine – as well as all of HMV’s 7”, 10” and 12” picture sleeves of this period – was done at Coulls Sommerville Wilkie Ltd. Their handsome building on the corner of central Wellington’s Johnston and Featherston St (still extant but disfigured by awnings and a dowdy paintjob) was just a few blocks from HMV’s Wakefield St office.

Artwork and layouts (known as “paste make-ups”) for both magazine and record covers could be easily transported between the two offices. At Coulls Sommerville Wilkie Ltd they would be typeset and processed by the pre-press department, then printed and fabricated before being trucked off to Lower Hutt or Kilbirnie for filling, packing and distribution.

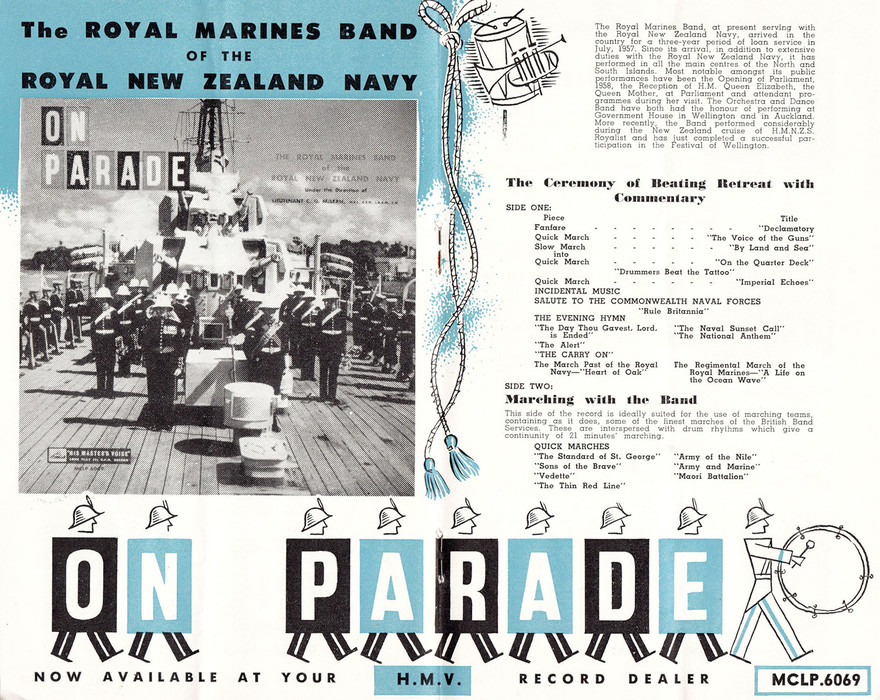

Incorporated in 1922 – but with roots in the early colonial settlement of Otago – Coulls Sommerville Wilkie Ltd was a respected commercial print company. As industry leaders in modern photolithography they were, by the late 1950s, well placed to capitalise on a soaring demand for records packaged in high quality colour sleeves. On Parade – a 1959 LP by the Royal Marines Band of the Royal New Zealand Navy – is something of a showcase for their technical skills.

On Parade

The marines on the scrubbed deck of HMNZ Royalist have an almost toy soldier-like rectitude. Beneath powder-puff clouds and cerulean sky the glittering Waitemata harbour competes with the glittering brass on the band’s uniforms.

Printed on a coated card stock – laminated for a full gloss – the LP cover is a jolly good show that must have made bandleader Lieutenant C.G. McLean a damned proud chap. The title is spelled out in what appears to be a variation of Commercial Grotesque, reversed from rectangles that bring to mind maritime signal flags or possibly bunting.

For the LP’s promotional centrefold in June 1959’s Present Records the cover is reconfigured, making explicit the toy box militaria with the additions of eyes-to-the-front and marching feet to top and tail the title.

It all seems rather lovely but the tin-soldier charm is somewhat deceptive. Shortly after On Parade’s cover shoot HMNZ Royalist was steaming to Singapore waters to bombard villages deep in the Malaysian jungle – part of the Commonwealth’s response to the MNLA’s struggle for independence from British Colonial rule.

DPS of On Parade (1959)

Military bands, whiteware, radio orchestras and torch singers – it’s the definition of an older generation, the conservative New Zealand society bracing itself against the rumbling youthquake. They were too late, the seismic event had already occurred.

Early 1956 saw the local release of a blue and silver labelled 78 featuring a Memphis guitar-slinger named Elvis Presley. “Pressed in New Zealand by His Master’s Voice (N.Z.) Ltd.,” heralded the disc’s sugar-paper sleeve. But the company’s grip on their new star was brief and by 1957 it was RCA NZ who had Elvis firmly in hand.

In Part 2 of Sound and Vision 7 we’ll look at how HMV (NZ)’s magazine framed Kiwi musician’s response to rock and roll, and the company’s launch of the parlour-shaking audio breakthrough of 1959: S T E R E O!