In November 2007 Pat McMinn shared memories and images from her photo album.

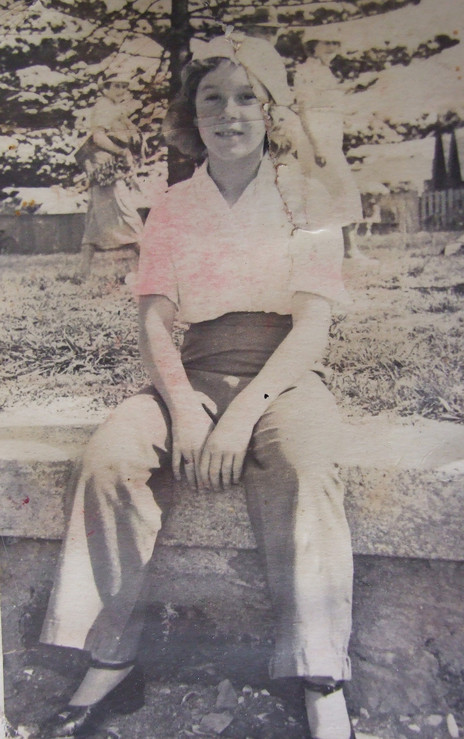

Pat McMinn, mid-1930s. As a young dancer she won 300 medals and 100 cups, and she was teaching dance from the age of 16. - Pat McMinn collection

You started off as a singer aged nine, in 1936, with the 1ZB radio programme Neddo’s Jolly Pirates. What was the show like?

It was a children’s show. Uncle Tom’s bring-your-own choir was about the same time: catering for children. It was a Saturday afternoon and it had lots of young people in it. A woman called Pixie used to play the piano and we’d just sing songs. I remember I sang ‘Alexander's Ragime Band’ and the songs of that era, and they’d just say “This is Pattie McMinn and she's going to sing so and so” – and the piano would go and I’d sing. It was all unrehearsed, straight to live. It was down in the Kings Arcade where the ZB studio was.

You toured with JC Williamson’s as a young dancer.

Yes, I was a dancer, I was only about seven or eight in The White Horse Inn. Everybody was from Australia except Bill Edgerton was in the band. [Edgerton was later an Auckland bandleader and president of the Musicians’ Union.] We travelled for about four months, right around New Zealand. We went to school at the different places we went to. [For example] we went to Wellington and Palmerston North – it was a big show – and to local schools. The roles for the young dancers weren’t very big but it was important enough so they had to have the experienced children. They couldn't pick them up in the different centres, there was too much to do. I had to have my hair cut all short because I took the part of a boy. [I played] mostly boys.

At age 16, in 1942, McMinn became the singer at the Dixieland cabaret on Queen Street, Auckland. “My grandmother entered me in this competition; they were looking for a new vocalist. And she put my name down. We lived in Wellington Street [Freeman’s Bay] at the time. I was annoyed about this because it was done unbeknown to me, but I won the competition. I had to go along and sing in the Cabaret: I was only about 15 or 16, the youngest one in the competition. I sang with Johnny Madden and Jack Thompson was playing the piano.”

She was paid 15 shillings a night. Between sets, McMinn would stay in the dressing room, knitting. “I wasn’t supposed to mix with the customers.” McMinn moved to the Trocadero, further up Queen Street, playing six nights a week. Len Hawkins took over as band leader, and from there the band moved to the Orange Ballroom on Newton Road. “I was manpowered [during the war]. I used to get up in the morning and work at a sack factory. I worked there and then went straight across the road and started to teach dancing. Then I’d get myself all dolled up in my long frock and go to the Orange and sing. So that was my life.”

Pat McMinn with the Trocadero band, Auckland, c. 1943. From left: Len Hawkins, Ernie Butters, Bill Egerton, unknown, Pat McMinn, Thomson Yandall and Jimmy Johnson. - Pat McMinn collection

Pat McMinn bought her frocks at a shop on Karangahape Road, which would phone her when new stock arrived. - Pat McMinn collection

What were the audiences like in the cabarets?

I used to get a little bit put out the way some of those women used to drink. They’d come in dressed all beautifully with their hair all done, and towards the end of the evening they’d be all tousled and staggering around.

Were the Americans well behaved?

Yes [though] we’d get a few who got a few under the belt, and I think that’s what put me off. I was invited to go down to a table by an American captain – “Come down and have a drink honey”. So I went down and it was, “What would you like to drink?” I said, I’m sorry I don't drink. “Have a cigarette”. I’m sorry I don’t smoke. “You don't drink and you don't smoke?” No. “Well you must be hell on the men.”

As well as singing at the Trocadero, McMinn took part in floor shows. She was also part of a singing/dancing duo with Toni Savage, a blind girl who played the accordion. - Pat McMinn collection

Ted Croad’s band at the Orange Coronation Hall, Auckland, late 1940s. From left: Crombie Murdoch, piano; Pat McMinn, vocals; Eddie Croad, drums; Ted Croad; George Campbell, bass; Tommy Simpson, tenor; unknown trumpet; Jim Watters, tenor; Lou Campbell, trumpet; Jim Warren, trumpet; Gordon Lanigan, alto; unknown trombone and tenor. - Jim Warren collection

After the war McMinn joined the Ted Croad big band, which had a residency at the Orange Ballroom on Newton Road. Croad paid well, so he was able to hire the best musicians. “People would stand along the front. You know how people do? Instead of dancing they would just sort of stand in front of the stage.” Among the musicians was Croad’s son Ed Croad, a drummer who would become McMinn's first husband. However Croad senior was a stickler as a band leader, insisting on punctuality, good deportment – and he forbade McMinn from dancing while the band played without her. “He was a horrible man,” she recalled with a laugh. “He finished up being my father-in-law and they used to call him the penguin because he always wore tails.”

Each summer Auckland's leading musicians headed to the Bay of Plenty to perform for holiday makers. An unforgettable gig was at Whangamata in late December 1953, just after the Tangiwai train disaster. Despite the national feeling of gloom, McMinn, her musicians and the audience donned fancy dress.

Among the musicians in McMinn’s band at Whangamata in summer 1953-54 were saxophonist Colin Martin, trumpeter Murray Tanner, and pianist Crombie Murdoch. “He was an out-and-out jazz pianist but he could play honky tonk which, as it proved [with his song ‘Opo the Crazy Dolphin’], made him more popular than for the jazz. Although people respected him as a jazz player, he made more of a name for himself with his recordings.”

Revelry in Whangamata, late December 1953. Pat McMinn with Murray Tanner on trumpet, Brian Spence on drums. - Pat McMinn collection

After the Korean war, in 1953 and 1954, Pat McMinn made two tours of duty to entertain the New Zealand troops stationed there. The entertainers had to be multi-talented as they performed comedy skits, magic tricks, as well as playing music, singing and dancing. The 1954 contingent included Johnny Cooper, the “Māori Cowboy”. She recalled, “I was a pretty tough sort of cookie, I put up with most things. I’d been brought up in the hard world of not rich, you know having to put up with things, and I was able to cope. I didn’t get sick or anything like that. And we were under very trying circumstances. No privacy.”

New Zealand entertainers in Korea, 1953. From left: Ulric Williams, Pauline Ashby, Pat McMinn and Des Begg.

Pat McMinn takes part in a singalong at the New Zealand base camp, Hiro, Korea. - Pat McMinn collection

Pat McMinn visits the 38th Parallel while visiting Korea to entertain New Zealand troops, 1953. - Pat McMinn collection

In 1969 Pat McMinn was a guest on the NZBC TV series A Girl to Watch Music By. The hosts were Max Cryer and Ray Columbus, whose ventriloquism skit became legendary.

In 1976, Pat McMinn was awarded a prestigious Benny Award by the Variety Artists’ Club of New Zealand. At the presentation, Lou Clauson adjusts the microphone for a speech by Prime Minister Robert Muldoon. - Pat McMinn collection

The VIPs assemble in 1976, the night the Variety Artists’ Club of New Zealand presented Pat McMinn with her Benny Award for services to New Zealand entertainment. From left, Thea and Robert Muldoon PM, Lorna and Lou Clauson, Pat McMinn, Auckland Mayor Sir Dove-Myer Robinson and Mayoress, his niece Barbara Goodman. - Pat McMinn collection

In 2002, when a digitally remastered CD of Pat McMinn’s 1950s recordings was released as Still Entertaining, she told the Sunday Star-Times, “I've never stopped entertaining.” The compilation “sounded like a good idea, I thought. I was a bit of a pop idol in my time and lots of people still remember me so perhaps there’s a market for this.

“At least I’ll sell seven copies. My nieces and nephews will have to buy one.”

--

With thanks to Michael Colonna of the Variety Artists' Club of New Zealand