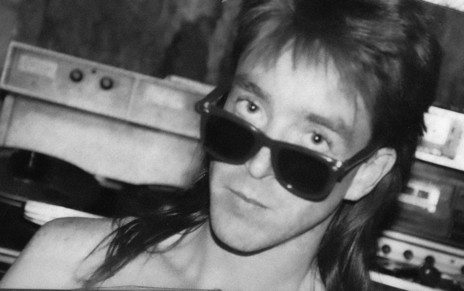

Paul Streekstra during the recording of Hello Sailor's 1986 album Shipshape and Bristol Fashion - Photo: Harry Lyon

When a band plays live, their sound is regulated by the person standing behind a mixing desk back in the crowd. In a studio, sound recordings are made by the artist, a producer and a recording engineer. From the late 1970s Paul Streekstra played a big part of New Zealand’s recording and live music industries, recording some of our best-known songs and musicians, and touring the country with all kinds of acts as their sound engineer. The recording sessions included Blam Blam Blam, DD Smash, The Screaming Meemees, The Topp Twins, Graham Gash, Hip Singles, The Gurlz, the Web Women’s Collective, Daggy and the Dickheads, Big Sideways, the Willie Dayson Blues Band, Mahinaarangi Tocker, Katango, Soul on Ice, and Hello Sailor. Paul passed away on 8 August 2025, from cancer.

Paul Streekstra's parents Klaas and Althea. - Streekstra family

Most people pronounced Paul’s last name incorrectly. Streekstra’s ancestry was not Dutch, he often said, but Frisian, and he pronounced it “Strake-stra”. His Frisian father, Klaas, moved to New Zealand after the Second World War with his wife Althea and farmed at Rimu, 16km east of Invercargill. – Bryan Staff

Mark Mckenzie – on the school bus

I first met Paul when we started high school which must have been in 1970. We both went to James Hargest High School in north Invercargill, and travelled daily into Invercargill on the same bus from rural Southland. We would talk and laugh but we were always in different classes and so had different friends at school.

Paul and I stayed at each other’s farms over the odd weekend. We would just do farming things. His father would enjoy having us on a bit with a cheeky smile. I enjoyed talking to Klaas about his upbringing in Frisia, especially over the Second World War. He would recount watching the Allied bombers returning at dawn from a bombing raid, hugging the ground to avoid German radar detection. I had the impression that Klaas would have preferred Paul to have a career in farming than in music. They would sometimes rub each other up the wrong way, but I think in many ways they were pretty close. Paul must have picked up the veggie-growing bug from his father.

Paul Streekstra on cello, age 11. - Streekstra family

Paul introduced me to heavy rock which we both loved; we’d listen to Pink Floyd, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin. I never learnt music but Paul played the cello in the Invercargill Youth Orchestra. I remember him having an electric guitar but I’m not sure if he had borrowed or owned it. My mother was keen to hear some classical cello pieces from Paul but instead was aghast to be confronted with the loud bass guitar picking along to Black Sabbath’s ‘Fairies Wear Boots’ playing on vinyl.

I remember we went to a Split Enz concert in Invercargill together: the tailored bright costumes, music, and robotic dancing were fantastic. After he left school Paul got a job with the Invercargill radio station 4ZA. I think Paul was still living at home while working at Radio New Zealand; I was still at school. But I remember visiting him the odd evening at work at 4ZA, once was when he told me he was babysitting the “pissed” evening announcer.

Bryan Staff – late nights in Durham Lane

I came up to Auckland as a relieving announcer at 1ZM in June 1977, taking up a full-time position a couple of months later. Apart from doing a shift on air, announcers recorded commercials and other snippets with a technical operator. There were two of those servicing 1ZM and 1ZB and one was Paul Streekstra. He often came in at nights with his friend Ian Morris who worked as a recording tech at Stebbings. 1ZM was presenting Radio Workshop concerts featuring local bands in the Radio Theatre in Durham Lane where both stations were situated. Peter Fyers, a programmes officer, would also run cables across to His Majesty’sTheatre, and Paul became interested in recording bands.

Peter Fyers – sounds of the city

Paul Streekstra and Peter Fyers at 1ZM radio station, 1977 - Peter Fyers Collection

We recorded about 30 bands in the Radio Workshop studio [RNZ, Durham Lane, Auckland] during the mid to late 70s, starting with Street Talk, Hello Sailor, and Th’ Dudes. These recordings were a mix of studio and live-in-concert sessions; the studio sessions were broadcast in a series called Sounds of the City, and the live sessions as Radio Workshop concerts. The bands used the tapes themselves as demos to solicit work in other venues, and ZM used the best tracks as playlist material in general programming. As a result, many of these bands gained popularity, signed contracts with record companies, and forged long term careers in the music industry.

Bruce Duske and Paul Streekstra in the control room of RNZ's Radio Theatre, Durham Lane, Auckland, 1978. - Photo by Bryan Staff

Initially, Bruce Duske and Keith Jolly were the engineers for these sessions. Paul was a young operator recording interviews and commercials upstairs for 1ZM and 1ZB. He was interested in the bands we were recording downstairs and wanted some training on the multi-track desk in the Workshop. He got pretty good at this and later took over from Bruce and Keith as the go-to engineer.

Paul Streekstra in 1977. - Streekstra family

Paul wasn’t involved in the original Street Talk-Sailor-Dudes sessions, but we did record these bands more than once over several years so he may have been involved later on. I did bring Paul in after-hours one night to play all our tapes for American record producer Kim Fowley. This resulted in a record contract and album for local band Street Talk.

Paul was really good at his work and very enthusiastic. We spent a lot of time in the studio after hours, recording, remixing and reviewing the tapes. The day-to-day details are a bit hazy some 50 years later, but the highlights are pretty clear. Whenever I think about Paul, I just get a warm glow and remember what a great guy he was.

Rikki Morris – use your f’n ears!

My first memory of Paul was seeing him at that Dudes live show at 1ZM in 1978. I could see him up in the rafters, through a glass window, which is where the control room must have been. He ventured down to check the mics on stage just before the band came on. Paul may have been picking up a few pointers from Ian at Stebbing’s, but he was pretty handy by that stage himself.

Ian Morris of Th' Dudes soundchecking at Island of Real with sound engineer Paul Streekstra, May 27, 1979. - Murray Cammick

Then of course in early 1979 Th’ Dudes hired Paul to be their live sound engineer. I had been the band’s roadie for a couple of months when Paul joined the crew. Along with me, lighting guy Murray Gray and road manager Keith McKenzie, Paul instantly brought a high level of professionalism to the band’s live shows. Paul insisted the band hire the best possible PA and mics (from Greg Peacocke and Paul Jeffery at Oceania). We toured relentlessly during 1979 and into 1980. Paul became a close friend.

Paul Streekstra setting up a rooftop gig. - Streekstra family

In early 1980, Paul decided he had had enough of the constant touring and the madness that came from that. We were on tour in the South Island – Oamaru, to be precise. Paul took me aside and told me he was “going home tomorrow, and Rikki, YOU are going to be the new sound guy!” So, one afternoon at the Bryden Tavern, Paul taught me how to set up the Dudes’ PA system and gave me a crash course on how to operate the mixing desk. “It’s all about the gain structure!” “Use your fuckin ears!” These are two things that have stayed with me over the years.

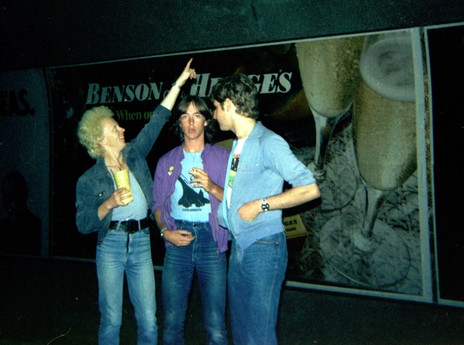

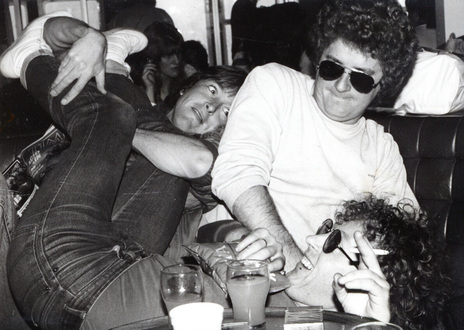

Rikki Morris and Paul Streekstra in Sydney, 1982.

In 1980, after Th’ Dudes broke up, I was mixing Lip Service and Paul was mixing Coup D’Etat. We were out one night and decided we would quite like to “swap bands”! So we did! When I moved to Sydney with The Crocodiles in 1981, Paul came and stayed at my house when he travelled across to master the Blams’ album Luxury Length.

Doug Rogers – great sounding records

Paul worked at Harlequin on Albert Street from the beginning until developers shut us down and never built the replacement building, so New Zealand lost a great studio where great records were made.

Beginning in 1983 Harlequin Studios was contracted to record Radio With Pictures’ Live at Mainstreet concerts so that they could be released on disc. Seen here at the cabaret, with a desk borrowed from Harlequin, are the studio’s engineers including Doug Rogers (centre) and Paul Streekstra (in stripes).

We worked together on many of the biggest projects for over five years, he was a major part of our success at Harlequin, he had incredible ears. [He was] New Zealand’s best recording engineer at the time in my opinion, and a really nice gentle person. It’s so sad and tragic he passed away at a relatively young age, and will be missed by so many. The good news is all those great sounding records he made for the New Zealand artists will live on forever. Unfortunately, our Harlequin inner circle is fading away. In addition to Paul we have lost Rhys Moody (also to cancer), Ian Morris, Graham Brazier, Dave McArtney … these wonderful people were highly influential in New Zealand in the 70s/80s/90s.

Tim Mahon – a lovely noise

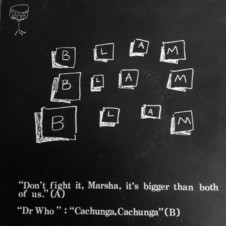

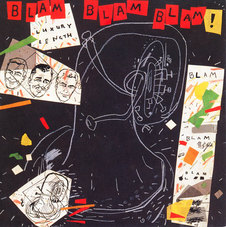

I feel like I knew Paul Streekstra all my life but we first met at Harlequin Recording studios in 1980. Blam Blam Blam was the reason. He was our engineer and producer for all our recorded product except ‘There is No Depression in New Zealand’ – that was done by Doug Rogers.

Blam Blam Blam - 'Don't Fight It Marsha, It's Bigger than Both Of Us' b/w 'Dr Who', 'Cachunga Cachunga' (Propeller, 1981). Sleeve art by John Reynolds. Produced by Paul Streekstra.

Paul had an incredible work ethic; he would work till he dropped then he’d have a cuppa and continue. Midnight-to-dawn sessions were the name of the game in those days.

Paul was a perfectionist and really did get a lovely noise for us. During the Harlequin days he was often working 18-hour days. He engineered and did live sound for The Gurlz, and he came on tour with the Blams and the Gurlz.

Fast forward to London in the mid 1980s, when Paul recorded a demo for Carol [Varney, ex-Gurlz] and I on my cassette 4-track, using brand new digital gear from Dream Hire – great times.

Fast forward another decade and Paul and I had a band called South that comprised John Wallis on vocals, Ian Gilroy on drums, Paul on guitar, and myself on bass. We played a couple of gigs including Mountain Rock. Paul was an exquisite guitar player.

Fast forward again and there’s Paul helping me with mixes for my brand-new material by me sending WAV files and him adding his magic.

Aotearoa has lost one of our very best engineers but more than that we have lost an extraordinary human being. His legacy will continue forever as Kiwis listen to DD Smash, Exponents, Blam Blam Blam, Gurlz, Topp Twins and his many other projects both published and non-published.

Paul built an aqueduct for our listening.

Don McGlashan – sense of play

Paul had this amazing childlike energy about him. You can hear it on Luxury Length. ‘Respect’ is a really early one, which is essentially just a rant, we’d come home from a school concert – a strange PEP gig in the community, that era’s counterpoint to WINZ. We told them we were a music theatre group; we weren’t at all. There were some sketches, very rough. One was a fairly feeble but pointed anti-Muldoon sketch. The deputy headmaster had a go at us, and I went home and wrote it down verbatim, it’s just a groove with this authority figure ranting over the top.

Paul Streekstra with Harry Champion and Don McGlashan at Blam Blam Blam's Paekākāriki gig, 2019.

Paul just ran with it, it wasn’t really a song. I was interested in rhythm delays on percussion, delays that fed back, like you get in dub music. He just ran with that and had a ball with it. Ended up with a strange sounding track we hadn’t anticipated, that was all Paul. ‘Luxury Length’ – he puts a vocal in at one point, around where Mark’s singing “my fingernails” – a strange lead comes in there and it’s Paul. He wasn’t a normal producer, he was jumping round studio, getting on mic and being part of the action.

That was the first serious album any of us had made. That idea of no-holds barred, anything goes, set the tone. We didn’t know what we were doing, we had drunk quite deep from the punk ethic: “too many chops were untrustworthy”. In spite of that, we loved the studio, and what we could do with it. With Paul’s help we set off fireworks, inside, and he recorded them all. We were goofing around.

It was finding delays and finding weird sounds. I think he came into his own when we were doing Luxury Length, there was a little bit of a gap when [Queen producer] Roy Thomas Baker and his main engineer came and did a workshop in Auckland. We did ‘Time Enough’, which ended up on the album. That’s quite different – everything’s tripled, played quite precisely. We didn’t like his mix, so Paul re-did it with us. All I can remember is questioning everything, pulling apart the drum set, recording every bit of it separately; banging on a carpet or door as a kick drum. Screwing around with sound.

He certainly deserved the co-producer credit, he put so much energy into it. There was this marvellous sense of play, and later on he ended up teaching recording engineering: I can’t imagine a better person. You’ve got to have an open mind. There are so many orthodoxies – “you’ve gotta play this way to get a hit”. Where’s the fun in that?

He was a real gentleman, he had a big generous heart, I’m so glad that in our early days when we were quite raw – and would have been susceptible to bullying or flattering or all the other things that happen when you’re young in rock’n’roll – that the guy helping us to realise our ideas had such a good heart.

Dave Dobbyn – in his element

Th’ Dudes met Paul at Radio New Zealand’s Durham Street radio workshop – a building that is no more, a crying shame – and he ended up working for us long time. He came to Australia when we went over there. The Australian road crew gave him a hard time – punched him out – but he was a real joy to have around, he got a great sound. Times were lean but we had this team, and we kept touring, though I felt desperately homesick.

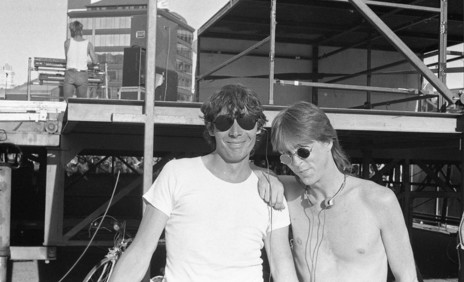

Paul Streekstra in Sydney with Th' Dudes' Dave Dobbyn and Lez White, 1979. - Ian Morris

He had such a grounding at RNZ, and to him it was a lot of fun adapting to what bands were doing – us and other artists. He took a shine to it; it was less constricting than working in radio. A lot more fun, and he was into the party of it all, which was good.

Paul Streekstra with Th' Dudes' bassist Lez White, 1979. - Ian Morris

Paul made sure the PAs were good. Murray Gray was our lighting man, and he’d make sure we disassembled the sound meters at every gig so we didn’t freak out the men in white coats who would take decibel readings – it was a game. Paul went to great lengths to improve the sound. We would hire our PAs from his connections at Oceania. We knew he was the man when it came to sound. He was invaluable that way, and it was confirmed from all the reports that came back.

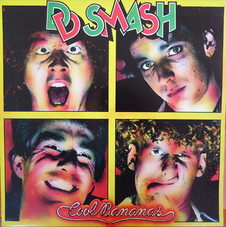

We were working on Cool Bananas at Harlequin when Roy Thomas Baker came in. Baker bumbled his way through things – at super top volume, the loudest I’ve heard anything – and when he left, we were happy to carry on with Paul. I remember having a great time. We must have recorded the album in about a week, it wasn’t much more than that, because we’d been playing the songs live. We got it down fairly quickly, which is what you want.

DD Smash - Cool Bananas (Mushroom NZ, 1982)

I think he had a good feel for it, and he knew all the gear very well, he could separate the guitars and make sure we had good things happening. Just to get the sourced sound as clean as possible.He had his desk tricks, double tracking, all sorts of things. He was in his element. We trusted him implicitly, and it paid off.

Thinking of Paul, he had a green/hippie philosophy, which was good. I remember him being quite urbane, and quietly cultured. He knew his stuff and he didn’t mind telling you. We never really had disagreements, but I remember shouting at him one night after a concert at Mainstreet. I was in a shitty, it wasn’t a good gig, and he was very forthright. He stood his ground. It makes for a healthy adversarial relationship.

DD Smash on tour: Paul Streekstra (soundman, producer), manager Roger King, Dave Dobbyn, circa 1983 - Photo by Kerry Brown, Murray Cammick Collection

Sound engineers Roland Morris and Paul Streekstra backstage at the Thank God It's Over concert, Aotea Square, Auckland, 7 December 1984. Paul was working as sound engineer for DD Smash. - Photo: Bryan Staff

He was someone you could really rely on. That’s important to us, especially back in Australia with Th’ Dudes, it was quite fraught most of the time. All those thousands of miles and RSL gigs – it’s just really taxing on the crew. But he bore it well.

He had a great, big, loud laugh. I trust a man with a loud laugh.

Debbie Harwood – without ego

I drove up to Auckland wanting to sing – having been in a band for two years, working every weekend, in Hawke’s Bay. I turned up at Harlequin within days to ask if they had any work there ... they didn’t but they needed their walls painted. So, up the ladder I went. I met Paul Streekstra on the first day. The engineers were all freelance ... I remember they were paid $10 an hour and Paul was a brilliant engineer and producer.

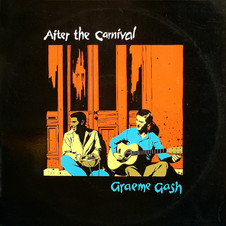

Graeme Gash - After the Carnival (Siren, 1981), engineered by Paul Streekstra

He had a calm about him ... a knowing – which I realise now was rare in such a young man. He didn’t doubt himself for a second but sans ego. His work on After the Carnival by Graham Gash was astonishing.

I saw Paul as a friend first and foremost ... such a nice man who didn’t seem to get bruised and battered by the rigours of live sound or the insane working hours of a studio engineer.

Simon Grigg – elevating the standards

I’m not sure when I first met Paul, but I believe it was during his time with Th’ Dudes. We became mates a couple of years later – a couple of years? It felt like decades later at the time – when I started working regularly at Doug Rogers’ Harlequin Studios in Auckland’s Albert Street.

Paul learnt engineering at Radio New Zealand in the 1970s, but it was at Harlequin that he was encouraged to hone and broaden those skills. Propeller was a young record label with some successes already, and Harlequin was the studio we chose to extend those. We needed allies, and two young, talented, and adventurous engineers provided just that: Steve Kennedy and Paul Streekstra.

In Rip It Up’s June 1982 edition, Don MacKay, in his review of Blam Blam Blam’s Luxury Length, talked of “the first blast in earnest of the independent label assault on the album market,” which that album was crucial to. His review was strong but, in particular, he called out Paul’s production skills, which elevated the record.

The John Reynolds designed sleeve for the 1982 Blam Blam Blam album Luxury Length.

This was no accident. Both the band and the label quickly came to depend on these skills. Once we bit the (very risky) bullet and decided to jump into the recording of Luxury Length, there was never any doubt about his role in the recording.

However, it was more than that. Paul had, in turn, elevated the standards for a new, younger generation of audio engineers and producers. One of those, Nick Morgan, who would go on to establish his name as a significant engineer and producer in later years, recalls: “I worshipped Paul Streekstra’s work and thought he was the greatest engineer I’d ever heard. The kind of free and flowing style he had as an engineer was unique.”

Nick was not alone. In the years that followed, countless aspiring studio boffins would similarly talk about Paul’s skills and how they had transformed the way we make music in New Zealand.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of that generation of young, risk-taking, and inspired music producers and creative engineers to our industry’s aspirations. Led by Paul and a handful of others, they helped elevate the recorded music we were making in Aotearoa to a level where we could take it to the world—which we did. We owe them.

Lisa McKelvey – connection

I met Paul on the 28th of November 1985, almost 40 years ago. I’d been invited to Rip It Up magazine’s 100th issue party by my good friend Michelle Tucker, who was working for her dad Glyn Tucker at Mandrill studio. It was held at the Six-Month Club above the old Cook Street Markets and I was 20 years old. I’d gone up to the bar to get my round of drinks for Michelle and our mate Murray Couling.

Paul Streekstra and Graham Brazier. - Streekstra family

The most handsome man I’d ever seen was standing at the bar between two friends (Dave McArtney and Graham Brazier from Hello Sailor. I think they’d come up to the party for a break from working on Shipshape and Bristol Fashion).

I fell for Paul right away – truly love at first sight! This beautiful man with intense blue eyes, sharp cheekbones and stunning mullet offered to buy my drinks in his deep, melting voice. When I went back to Murray and Michelle they told me his name. I’m afraid I was shameless and stalked him – I went to a record shop in Queen Street (when they had such things) to find Harlequin studio’s address to send Paul a letter to ask if I could buy him a drink or two to pay him back. So we ended up going for evening drives up Maungakiekie – or One Tree Hill as we called it then – whenever he had a break from the studio.

Then Paul went off for his OE in London for three years, I moved to Wellington, and life happened. He wrote beautiful long letters filled with poetry and funny observations about life for a while but then we drifted apart.

Carol Varney – all about the sound

“Size 10 ears” – I don’t know if he coined it, but Paul – certainly he said it and absolutely it applied to him. He was all about the sound, generous and patient. It didn’t matter if it was Doug Roger’s fancy pants Harlequin studio, he gave us Gurlz – who had been playing our instruments for a couple of minutes – exquisitely shiny, newest of new, punkster-perfect pop waves. I still love ‘Six Million Dollar Man’. Thanks Paul.

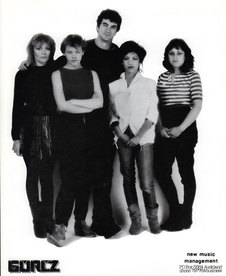

The Gurlz were a popular live band in Auckland in the early 1980s, releasing an Ian Morris and Paul Streekstra-produced EP on Harlequin's Ze Disc label in 1982. From left: Carol Varney (drums), Kim Willoughby (vocals), Greig Blanchett (guitar), Debbie Chin (bass), Shelley Pratt (keyboards/vocals). - Roy Emerson

In London, working in the confines of our centuries-old squat on Tim [Mahon]’s four track, I remember Paul obsessing over a terrible little new invention: a drum machine. It was to demo songs for Dead Sea Scrolls [which featured Mahon, Varney and others]. He never once said to me, “You’re a foghorn, stick to drums and lyrics.”

Mark Mckenzie – London calling

We met Paul again in Dunedin I think in the late 80s on his return from London. He looked very cool in his tight jeans, nice shirt, maybe a bandana around his neck and coloured shades. We were planning to also go and work in London and he told us about it. He’d had to talk his way into staying longer with British immigration. The officer liked that he had a Frisian name. He thought he was hard working so allowed him to stay on working for longer than the normal two years for Kiwis.

Dave Gent – why does love do this?

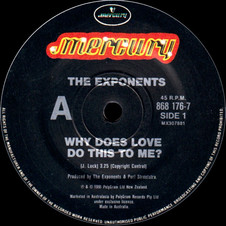

The Exponents had just arrived back from rock’n’roll oblivion in the UK. Adam Holt from Polygram had given us a deal based on the demos we had recorded and suggested we use Paul as he was recording all the best music in New Zealand at the time.

The Exponents' 1991 hit single 'Why Does Love Do This To me', produced by the Exponents and "Porl" Streekstra, who also engineered.

For the single we decided on ‘Why Does Love Do This To Me?’ and pretty much played it as we would have played it live, Paul left in all the crazy drum fills and bass intro, not to mention the arrangement – which didn’t make commercial sense. However Paul had great ears and understood what made the Exponents tick. I’m chuffed he kept my intro which is like a half-arsed rip off of the bass on ‘Don’t Dream It’s Over’. I hope he had fond memories of that session; it’s our biggest song and he was a big part in it.

Rikki Morris – that laugh!

In the late 90s Debbie Harwood and I hired Paul to come and help us set up The Bus studio in Devonport, in an advisory capacity – choosing speakers, a mixing console, compressors and preamps, and a top-quality vocal microphone. Some of that gear is still being used today in my home studio. Paul was an absolute whizz in the studio, quickly learning how to use our brand-new digital recording system, Soundscape. Paul also taught me how to use Soundscape during that time.

He did a fair amount of engineering at The Bus, working on all sorts of different projects, including a commissioned album for the 1999 Netball World Champs. Paul also brought quite a few artists and bands to record there. Kāren Hunter and Terra Firma are two I remember off the top of my head. When I bought a new Soundcraft TS12 console for The Bus in the early 2000s, Paul helped me install it. “THAT fuckin’ console!” he used to call it! Lovingly, of course!

In later years, we met up and texted far too infrequently, mostly to talk about our love of cricket! We went to a few one dayers at Eden Park together and would occasionally drive to Hamilton to watch a day of test cricket at Seddon Park. Paul was such a lovely man. He was kind, intelligent, clever, talented, charming, sometimes LOUD, and he had a wicked sense of humour. That laugh!!!

Harry Lyon – passion and humour

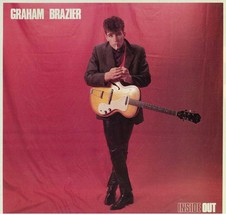

I really got to know Paul when I managed Harlequin Studios in 1984-85 where he was the senior and go-to engineer. I did a lot of recording with Paul over the years. He worked on Graham’s Inside Out, Dave’s The Catch, Hello Sailor’s Shipshape and Bristol Fashion and The Album. He was a perfectionist with a great sense of humour – having both made him wonderful to work with. He worked at MAINZ [the Music and Audio Institute of New Zealand] for many years with Dave and I, inspiring countless aspiring audio students with both these qualities.

Graham Brazier's classic 1981 album Inside Out, recorded at Harlequin Studios, Auckland. The album was produced by Graham Brazier and Dave McArtney and engineered by Paul Streekstra.

As the Dean at MAINZ, I was privy to all tutor student evaluations and staff performance appraisals, so I know that his students and colleagues loved and respected him. He was a regular for Friday after work drinks at the bar on the corner in what I know we all thought was a golden era for a few years when we had the place rocking – good times and cherished memories.

Paul Streekstra mixing Hello Sailor's Shipshape and Bristol Fashion album with producer Liam Henshaw. - Harry Lyon Collection

I looked back over my message thread with Paul that goes back to our days at MAINZ. It includes his offers of heritage tomato seedlings, enthusiasm and help with re-mastering of Sailor albums for vinyl and digital release, cricket, our shared interest in lawn-edging perfection, and his prowess, how our post-MAINZ lives were going – and increasingly his health issues that he approached right to the end with grace and humour. We’re going to have a get together at that bar on the corner to remember what a key role Paul played in our lives. Arohanui old chum.

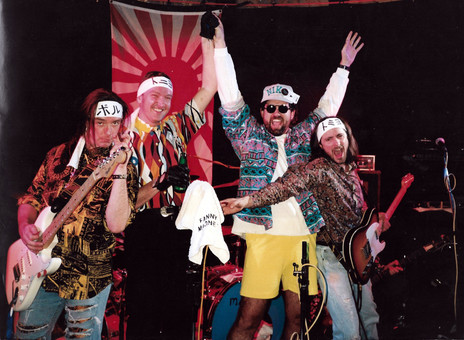

In the early 90s, Paul Streekstra worked at Radio Hauraki. While there, with colleagues on the station, he was a member of the band Fanny Magnets. This photo is from their last gig, July 1992.

Jean McAllister – MAINZ memories

By the time I joined the teaching staff at MAINZ, in 2004, Paul was a MAINZ stalwart, having taught audio engineering since the mid-90s when it operated out of a leased building on Symonds Street. He had seen the rise and rise of MAINZ as it moved into new Auckland city premises in Rainger House in 2000, with purpose-built studios, classrooms, rehearsal rooms, and an impressive line-up of music and recording gear. MAINZ was the place to be for any young person who had ambitions in the New Zealand music industry.

Paul Streekstra and Jean McAllister - Jean McAlister

My job was, at first, part-time – helping out on the Foundation programme. I had been a musician for many years, played in bands and had finished training as a primary school teacher when the job at MAINZ came up. Foundation was then a year’s course of study and designed to give students who didn’t have the required academic or music qualifications an opportunity to lift their skills, become better musicians, work in a live sound crew, get familiar with computer technology and record their original songs. The aim was for Foundation graduates to then go on to enrol in the higher-level programmes. Every year we would help produce an album’s worth of songs written by Foundation students and recorded in the MAINZ studios by groups of audio students with the supervision of their tutors. It was an ambitious and challenging project and the original setting for Paul and my working relationship.

Paul was usually working with capable and motivated audio students. They would have to have completed high school with a University Entrance qualification as well as produce some of their recordings as evidence of their suitability to be accepted into the audio programme. Foundation students on the other hand came from a huge range of backgrounds. We had kids who had no clue what they wanted to do, had hated school but loved music, older people who had worked but wanted to try music for the first time, youngsters who had been kicked out of home, some who had been in trouble with the law. There were the earnest kids who had five-year plans, kids who had fragile mental health, and gifted musicians and songwriters who needed a year to find out how much work they still needed to do. Every one had their own story. Our job as tutors was to give all our students the opportunity to develop their creativity, work together on something they could be proud of and learn a whole lot in the process.

Paul Streekstra considers his mic setup for a grand piano.

To his great credit, Paul understood the personal and professional dynamics involved in getting decent recordings of songs, some of which were just sketches of ideas when first presented. He gave respect and kindness and expected it in return. Everyone in a studio run by Paul understood that this was a place of work, where ideas could be explored but not necessarily make the final cut unless they had earned their place. I sat with Paul one day as he painstakingly edited and mixed one of our student’s songs and made it sound better than anyone could have imagined. That was just one of his great skills.

Having come from working in radio and in recording studios engineering albums by some of New Zealand’s most celebrated artists from the 1980s and 90s, Paul came to MAINZ with an enviable reputation and a wealth of experience. He was a microphone enthusiast and an expert in choosing exactly the right one for the task at hand. Students learned from him the science of putting a microphone in the right place to capture the essence of the sound.

Paul Streekstra, far right, with the MAINZ crew, 2018. - Jean McAllister

Musicians and audio engineers are both involved in the world of music but I have found that they tend to approach it in quite different ways. Often, audio engineers are excellent musicians but are more interested in sound quality and listen with a technical set of ears using a specialised vocabulary for describing music in those terms. Sometimes at MAINZ when I would hear audio tutors and students talking about a particular recording I would wonder if they were hearing the same things as I was! Paul knew the power of getting the details right but also managed to operate as a music fan who could hear what a song was trying to be and make it as close to that piece of art as possible.

Very soon after I met Paul it was clear we were going to be friends. We both shared a love of The Beatles, guitars, word games, and cricket. At that stage there were only a few other women on the teaching staff at MAINZ and at times it could feel like a bit of a boys’ club. Paul seemed to effortlessly understand that and made an effort to bridge the gap. We bonded over cryptic crosswords, funny spelling mistakes, misplaced apostrophes.

MAINZ felt like an independent entity but had always been governed by another polytechnic in the South Island and there were inevitable disagreements between the Auckland staff and those in charge about how to run the place. When one of our managers visited in 2018 and delivered the news that the economic picture was grim and jobs would be lost, there was stunned silence. As soon as we returned to our offices Paul sent us all an email with two biting, witty, hilarious versions of the manager’s name – as anagrams.

Paul Streekstra plays a tiny violin. - Harry Lyon Collection

In 2019, the audio engineering degree and certificate programmes at MAINZ in Auckland were cut. It was a huge loss. Audio had been for many years the flagship programmes at MAINZ and now all that talent and expertise was leaving the building. Paul moved to the Kāpiti Coast with Lisa and bequeathed the Foundation project studio his beautiful harmonium, which was played often by curious students who had to pump their feet to make it work.

Paul was a wonderful colleague and friend. He cared deeply about people and made it clear that he was on your side. It was so lovely when Lisa came back into his life in the 2010s and they were married in one of his favourite parts of the country – Central Otago. Paul was a happy man! He was fun to be with; his laugh would boom through the halls at MAINZ. Many of his students remained friends with Paul after they left and made their own careers. We all had a drink at the corner pub next to MAINZ as we had on many other occasions to say goodbye.

After he left Auckland, Paul and I stayed in touch, messaged and exchanged photos. We shared stories about what we were doing in our post-MAINZ lives. Our last conversation by text was just a few days before Paul died. I sent love and Paul expressed his delight that I had become a grandmother. I miss him dearly.

Lisa McKelvey – reconnection

In 2009 I stalked him again; this time, thanks to the internet. I looked up his name; by now he was working at MAINZ. We reconnected, I moved back to Auckland, and we got married at his parent’s place of worship, St Enoch’s church in Alexandra, Central Otago on 7 January 2014. Our brother-in-law the Rev Andrew Doubleday married us.

Paul Streekstra and Lisa McKelvey at home. - Streekstra family

After Paul’s redundancy from MAINZ we moved to Wellington (my family all live here, and my son David had recently married Lauren). Paul so enjoyed the gentle Kāpiti Coast lifestyle, especially when we moved into Manly Street in Paraparaumu Beach just before the second lockdown in 2021. Paul set up a studio in our house for his business – birdsongaudio.com is his website. He created adverts for local business with Hugh Walsh, continued to work on music production and voice work, and for the last few years was doing the sound for Pat McIntosh’s film about Coral Trimmer.

Paul decided to buy a lawnmowing business two years ago and his clients adored him. He’d take the time to chat to people as well as making their lawns look immaculate. When he’d finished for the day he’d do his maintenance with the garage door open and that’s when our neighbour from across the road, [publisher] Roger Steele, would pop over for a chat and a beer with Paul – they clicked right away.

Pat McIntosh – a musician at heart

We were The Susans, in Palmerston North, and we supported Hello Sailor on the 20th anniversary tour. Paul was on the sound desk. After our set we chatted about recording original stuff. It’s how he connected to people, he wanted them to record things: “Just come up into a studio.” He was really focused on getting people’s music on tape.

Meeting him there was no ego, it was about the music. We did an EP at York Street and I came back a year later, as a solo artist, dGARE. The album was 360 Degrees, he was producing it with me writing the songs. We brought him into one of the songs, which we played at his send-off; he wanted it.

We just connected, the creativity of what we were trying to say, the politics. We hit it off: two creatives that get each other. I loved his edge, his politics. He played the guitar like it was a cello. He loved his atmospheric edge when we were writing together.

What was it that Paul so special in the studio? He was a musician at heart. He was behind the desk, but a musician at heart. So, you weren’t intimidated, he made it really safe, and a lovely space to create.

He was so technically up there, on microphone placements, the grand piano at York Street sounding gorgeous. He loved microphones and miking things. He wasn’t in it for the rock stardom, he was in it to get people’s music recorded and to leave a legacy. But if he passionately thought the Paul way was the right way, he’d stand up and say it. He was adamant.

--

Paul Streekstra, interviewed by Pat McIntosh and Val Little on the Vinyl and Proud Show, Pae FM, Paekākāriki, 2021

--

A Paul Streekstra playlist

Paul Streekstra engineered and/or produced countless recordings of New Zealand artists, though not all are on Spotify. This is a selected playlist.

Contributors

Mark Mckenzie is a childhood friend of Paul Streekstra’s from Invercargill

Bryan Staff is a writer, photographer, radio host and founder of Ripper Records

Peter Fyers is a former Radio New Zealand producer

Rikki Morris is a singer, songwriter, and sound engineer

Doug Rogers is a sound engineer; he founded Harlequin Studios

Tim Mahon is the bass player of Blam Blam Blam

Don McGlashan is a solo artist, formerly with Blam Blam Blam, The Front Lawn, and The Mutton Birds

Dave Dobbyn – now Sir Dave – first worked with Paul Streekstra as a member of Th’ Dudes

Debbie Harwood is a singer, record producer, and co-founder of When the Cat’s Away

Simon Grigg founded Propeller Records and AudioCulture

Lisa McKelvey married Paul Streekstra in 2014

Carol Varney was drummer with The Gurlz

Dave Gent is bass player with The Exponents

Harry Lyon is a founding member of Hello Sailor, and was Dean of MAINZ

Jean McAllister was in Red Alert and The Drongos, and worked at MAINZ

Pat McIntosh is a musician and a host of Pae FM’s Vinyl and Proud Show, Paekākāriki

--