“I’ve been singing those sad, sad songs. Sad songs, all I know” – Otis Redding

Rick Bryant must be the hardest worker in local rock music. Talk about a busman’s holiday: for relaxation on his nights off with The Neighbours, his band with Sam Ford and Trudi Green, he has formed another band, The Jive Bombers.

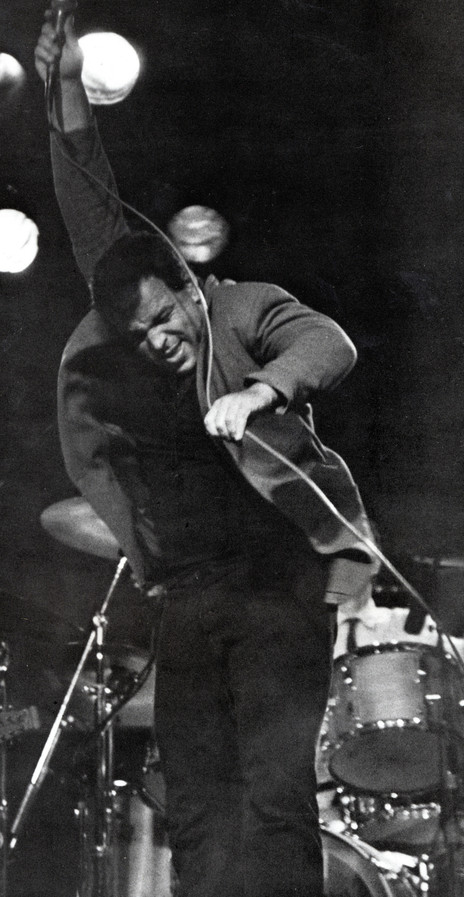

Rick Bryant with the Neighbours, Mountain Rock festival c.1982.

With Bryant in charge you know that you’re in for a heavy dose of R&B, and the Jive Bombers’ repertoire of “pure, unadulterated soul” gives him the opportunity to cover many of the classic soul tunes of the last 30 years.

That’s how it’s worked out. Because the Jive Bombers come from many other bands, they have only managed a half-dozen performances so far, but they have been so successful that they will soon get together for a short North Island tour. There is also talk of a live cassette being released.

The project is one Bryant has been planning for a long time. Still addicted to soul music after nearly 20 years in various bands, he’s finally doing something to satisfy his purist streak. During his Wellington childhood in the 1950s an obscure record of Caribbean jazz got him listening to music, and then he became aware of tunes on the radio such as Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’ and Elvis Presley’s ‘All Shook Up’.

“But obviously the Rolling Stones were the great popularisers of the music. Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley – they wrote the songs, so you checked them out. There was also a very specialised radio programme in Wellington run by a real music person [Arthur ‘Cotton-Eye Joe’ Pearce] who played all sorts of obscure pop music, which of course in those days that meant popular black music.”

“I read about Howlin’ Wolf on the Rolling Stones’ covers, and shortly after I heard him on this programme, and that was one of the things that changed my life.”

After playing British and American R&B in his early bands, Bryant progressed to a highly regarded country-blues band, the Windy City Strugglers, run by Bill Lake – now with The Pelicans – using mainly acoustic instruments.

Bryant then moved on to some of the legendary New Zealand bands of the early 70s: Mammal, who used to do gigs with a young poet called Sam Hunt, and of course the mythical Blerta.

While playing in Mammal, Bryant was earning his living as a junior lecturer in English at Victoria University. “I needed the money to pay for the band’s gear,” he says. “The dough was alright, but I’d rather do a good day’s work for a living.” He left when he became bored, and also because Mammal was about to go full-time. “We just about cracked it, but the bass player pulled out. We were bloody good, by the standards of the time.”

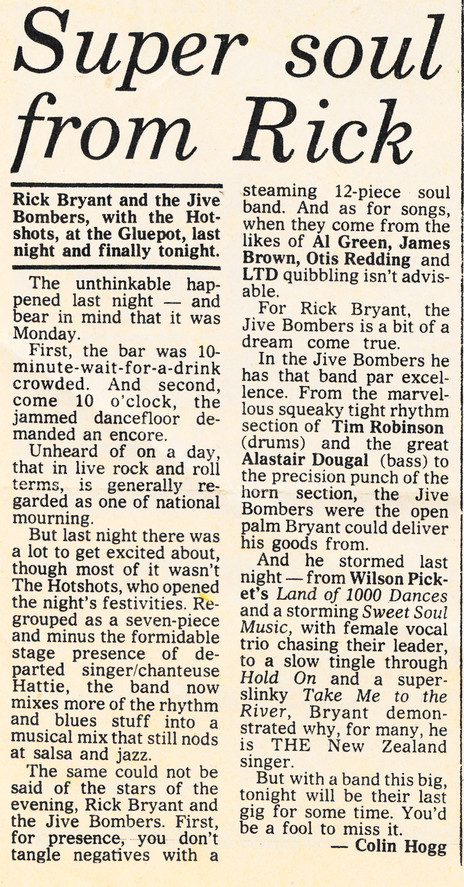

Colin Hogg reviews the debut performance of Rick Bryant and the Jive Bombers, Auckland Star, 1983

Bryant is considering releasing compilations of his old bands on cassette: “It won’t be an economic operation. There are a few people around interested in collecting New Zealand music. What we were doing then is comparable to what Flying Nun has done over the last two to three years – not upmarket, but underground. Quite a lot of musical effort and experimentation went into it.”

After a short period of what he calls “a sabbatical on a Justice Department fellowship” Bryant found himself without a job. So he formed Rough Justice and once more hit the State Highway in a bus: “I really had to go for it, it was just desperation,” he explains. “I figured it had to be very organised and look structured, partly for reasons of probation.”

Since then, it has been constant touring, with Bryant covering the country about four times a year. There is hardly a small town The Neighbours haven’t played.

Bryant leans his weight onto his back leg, taps the beat, and fills his barrel-chest with air.

Rather than occasionally slipping out of the horn section to sing a number, Rick Bryant takes centre-stage at a Jive Bombers’ gig. He takes the microphone in his hand and puts the stand to one side. The band has just completed its introductory vamp, but the dance-floor is already full. Bryant leans his weight onto his back leg, taps the beat with his other knee, and fills his barrel-chest with air.

“Raise your hand!” Bryant exhorts soul-lovers to stand up and be counted, in the words of Eddie Floyd. The horns are dancing, the organ swirling. Bryant has an ecstatic grin on his face.

In James Brown’s upbeat ‘I Can't Stand Myself’ Bryant stabs his mic into the air for emphasis and sways from side to side to the recurring guitar line. With a plaintive horn line, the band slows down and segues into the ballad ‘Pain in My Heart’ with its tortured crescendo: “come back, come back!”

Once again the band changes gear without a pause. “Do you like good music? (Yeah, yeah!)” Three female backing vocalists run on stage and immediately start twisting in their miniskirts. With their shrill response lines the pure soul sound of the mid-60s is complete.

The repertoire of classics doesn’t let up: an ominous ‘I Heard it Through the Grapevine’, ‘Chain Gang’ thrusting on the backbeat, and a jazzy ‘Hold Back The Night’. Each band member makes a subtle but vital contribution to the music. The horn section and the backing vocalists steal the limelight, but behind them the excellent rhythm section, keyboards and guitar, are the unsung heroes of the group.

Bryant’s vocal showpiece is Billie Holiday’s ‘God Bless the Child’. With closed eyes and a loose jaw, he concentrates on maintaining a strong, true, clear voice in the light jazz texture. Here, his playing with the rhythm is Sinatraesque, adding another style to his many influences: throaty Wilson Pickett, intense Otis, but most of all, the brilliance of Aretha.

In a well-paced, diverse set, the band takes more risks and gets more funky as the evening progresses. Finally they all take the frontline at the climax of Pickett’s ‘Land of 1000 Dances’, singing the chorus together.

Besides the total enjoyment of the band and the audience, the image one is left with is the total satisfaction on Bryant’s face. In the words of the silky Al Green number, “You make me feel brand new.”

IN CONVERSATION, THE TOPICS AND THE SPEED AT WHICH THEY ARE DISCUSSED IS BREATHTAKING

Behind the desk in his book-lined study, Rick Bryant is the image of both an Oxford and a Sicilian Don. He’s a fascinating conversationalist and the variety of topics and the speed at which they are discussed is breathtaking.

At one point he’ll burst into an R&B melody to explain an analytical point about soul; then he’ll leap up and consult Evelyn Waugh’s diaries to clarify an issue in the Waugh/Mitford relationship, his chosen field of speciality.

His day is filled with music, and listening to a Walkman while driving, cooking, or at his relaxation, gardening, is the only way he fits it all in. He acts as a mentor to young musicians, listening to their demo tapes, offering advice and encouragement to new artists.Whilst talking, he is monitoring the radio stations for New Zealand music. The godfather inference is not sinister, but reflects generosity: visitors call by constantly to discuss, say, Shakespeare – or to report on the door-takes of other bands that weekend.

As with all musicians, the conversation turns sadly to the politics of the local industry. With the lack of support from the major record companies, the answer for New Zealand music lies in the musicians organising themselves with the help of a few idealistic independents. “A quota for the radio-play of local product is a good idea, but an obstacle to it is the lobbying power of the radio people as compared to that of the local musician,” says Bryant.

Meanwhile the anecdotes and opinions keep flowing. With his constant travelling, New Zealand seems like one big town, and he remarks on the deviant sociology of some of its outer suburbs. “I envisage the possibility of a native-New Zealand style [in music] emerging. Music is the main communication between different social types who might otherwise fight. When you see people who are natural social enemies – disadvantaged whites and disadvantaged blacks – get on, it’s frequently through music. There are forces trying for interested reasons to increase racial tension, and music is going against that.”

“Do you like good music? (Yeah, yeah!)”

--

First published in Metro, December 1983