I would have been 16 or 17 when my mates and I wandered into Atlantis Market, a long-gone hippie emporium in Christchurch's Cathedral Square, and spied a stack of newsprint near the door. I picked up a magazine from the top of the pile and furtively left with it, unsure whether or not I was stealing it. I could hardly have known that three or four years later I would be in Auckland, working as Rip It Up's deputy editor.

Rip It Up is not the first writing about music that I recall reading. That would be Gordon Campbell's column in the NZ Listener (of all things, the one I really remember is his sharp review of a Billy Joel album). I have always been able to write, and this seemed like a way to write strongly, and with style.

I was still at school when I had my first work published, in Gary Steel's Wellington-based In Touch magazine (a review of a gig at the local teachers' college, headlined by a band called The Phantoms). But things really took off when I started as a cadet reporter at the evening daily Christchurch Star in 1981. By then, I was buying and reading the three-months-late NME most weeks, and I had my style heroes there, some of whom (come on down, Paul Morley) may not actually have been a good influence.

Moreover, there was so much to write about. My friends and I were already buying the records being released out of Auckland by Propeller and Ripper, and Christchurch itself was entering a golden era. We'd moved on from under-age gigs in suburban halls to sneaking into the Gladstone and the Hillsborough Tavern, which were pulling crowds not just at the weekend, but midweek. Word got about that year that Roger, the slinky dude who managed the Record Factory, one of the record shops on either side of the Square, was launching a record label to capture some of the local bands. Flying Nun, he called it.

I am greatly indebted to Rob White, the Star's music writer, for generously giving the new kid the chance to propose stories. One of the first was an interview with The Androidss, a lovely bunch of geezers who were only too happy to take the cadet journalist to the pub for the afternoon. Meanwhile, over at The Press, a young guy called David Swift was covering much the same beat.

At the end of 1981, I got the news I'd been dreading. Every year, the Star's most junior reporter was dispatched to work in the paper's Timaru branch office. And for 1982, that was me. It turned out okay. On a weekend back up in the city (which was actually most weekends), I went to a bizarre gig at Lincoln University. While the sons of farmers trashed the dining room – I think more food went on the walls than anywhere else – The Clean opened for the new band everyone was talking about: The Dance Exponents.

I wrote an … impressionistic review and sent it off to Rip It Up. The editor, Murray Cammick, published it and sent me an encouraging letter, politely noting that the review wasn't Rip It Up's usual style. What I didn't know was that he'd looked at my formatting and the particular imprint of my typewriter and realised that this was the kid who had a year earlier sent him a fairly pompous letter declaring that Rip It Up had become "paid advertisement for the record industry." ("I thought, better that than an unpaid advertisement," he told me later.) He could have been forgiven for filing my review in the bin, but he didn't.

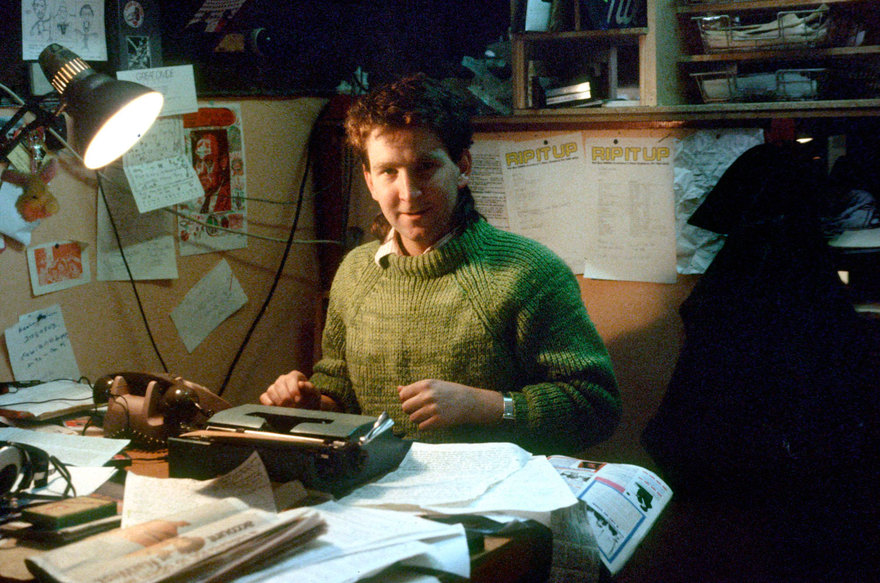

The young man with a mullet - Russell Brown in the Rip It Up offices circa 1984-5

Later that year, on another weekend in Christchurch, I ran into the Dance Exponents (who I'd got to know in Timaru) and their manager Debbie Harwood told me that Murray was hoping I'd apply for the new job of Deputy Editor. I had seen the ads and thought I couldn't possibly be qualified, but with this news I sent off my application. And so it was arranged. Murray would come to Timaru and interview me.

He arrived on the train and, we had dinner at a steakhouse and then went back to where I was living. In a brilliantly misconceived attempt to demonstrate my hip credentials, I put on Orange Juice's debut album, You Can't Hide Your Love Forever. Murray hated that record, largely for its cover of Al Green's 'L.O.V.E. Love'. Eventually he asked if I wouldn't mind taking the damn thing off.

Fortunately, this misstep didn't blow my chances, and I think he basically offered me the job that evening. The next day, my friend (and later, love of my life) Fiona Rae and I accompanied Murray to Dunedin, to see The Clean play what was supposed to be their last gig, at the Cook.

I broke the news to my bosses, wrote my first feature for the mag (a Hunters and Collectors interview), packed my car and headed for Auckland with a dreadful hangover. In that journey I went from being bored, frustrated and not entirely fitting in with the newsroom, to a life right in the middle of the culture I was defining myself by.

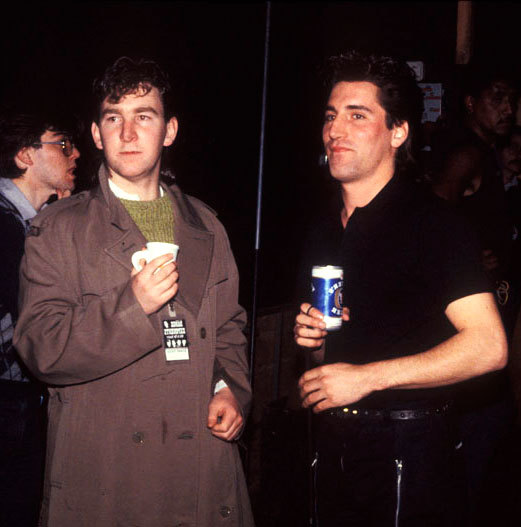

Chris Sheehan, Russell Brown, Jordan Luck, Brian Jones - October 1983 - Photo: Murray Cammick collection

I did feel I was part of the same creative pool as the people I was writing about – especially the Flying Nun bands. We were the same age, had the same interests (not least, getting wasted and seeing other bands) and even lived together. On one notable day, I met and interviewed a band called Children's Hour, went back to their house in Grafton, and, by the end of the evening, was their flatmate.

The Rip It Up office itself is now but a memory. The Darby Street building it was in has long since been replaced by a banking tower. Denis Cohn ran his gallery on the first floor, Snake T-Shirts had a booming business on the next and our space in the attic was shared by a young fashion designer called Ngila Dickson. Simon Grigg and Paul Rose ran Propeller Records from an office just across Queen Street. They were all kind to me, especially Ngila, who always called me "Rascal".

I do feel lucky to have been doing that job not only at a time when the music scene was flowering, but when Rip It Up was at its zenith. 30,000 copies were distributed for free every month, and it seemed like everyone read it. Some months, it felt like I wrote nearly everything in the mag. After we switched to computer typesetting, I certainly typed everything in it.

I discovered I was a decent, untutored sub-editor and that (when I wasn't too dazed and confused from the night before) I had a fair capacity for work. But most of all, I learned how to interview. I had the most marvellous subjects on whom to practise the trade. Malcolm McLaren gave me a wonderful, generous (and in retrospect, highly prescient) interview. I experienced the star power of Nico and grappled verbally with John Cale and Elvis Costello. I met Nick Cave and Michael Hutchence. I wrote about many people who would become my friends. I interviewed Wayne Elsey just a couple of days before he was tragically killed in a train accident.

I've often described Murray as the best boss I ever had, and I still think that's true. Working at Rip It Up nearly ruined me for conventional office jobs. We would have our bust-ups but they'd be over quickly. I think there was a degree of indulgence in him printing a few things I wrote. And he let me write at such length.

There was also the welcome chance to write for a pop audience, after Murray launched Shake! magazine, a local stab at a Smash Hits that, if I recall rightly, I came up with the name for.

Eventually, it was time to move on, and in 1986, I gave notice and headed for London, where I very nearly landed my dream job straight off the plane. David Swift kindly set me up for an interview at NME, where he worked as a sub-editor. I didn't fully grasp it at the time, but the paper was in turmoil. Its more intellectual writers were losing touch with the paper's audience, sales were slipping, and there was a furious internal debate about whether to cover hip hop or stick to white boys with guitars.

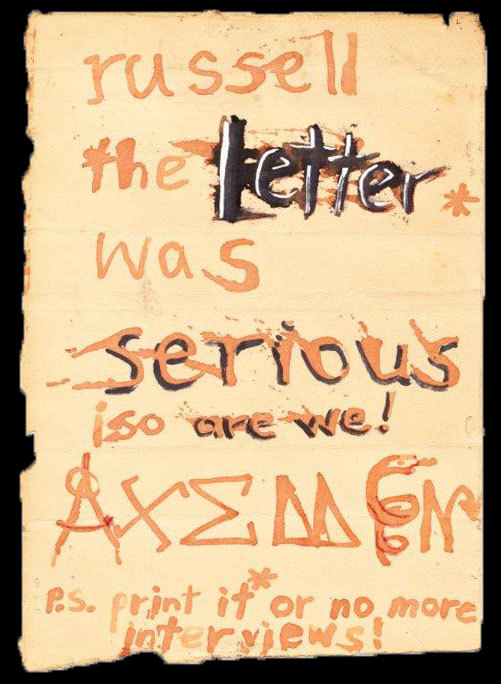

The Axemen write to Russell Brown at Rip It Up. The letter itself is lost in time.

They were impressed by the fact that I'd done Rip It Up's typesetting (British publishing was weirdly low-tech in those pre-Wapping days), but noted that I didn't have the layout skills they required. It was also pointed out, and they weren't entirely joking, that they had filled their quota of New Zealanders, thank you very much. Ironically, the former Mockers drummer, Brendon Fitzgerald (who I'd given a start to at Rip It Up) and Andy Fyfe (my old flatmate from Timaru) subsequently got sub-editing jobs there.

Instead, I wound up working nights at the HMV store in Piccadilly, and that was probably for the best. Journalists shouldn't be journalists all their lives. I had the chance to work out who I was, and continued to do the odd story for Rip It Up (one involved a very messy night with The Pogues).

Russell Brown and Jordan Luck - Photo by Murray Cammick

Via Karyn Hay, I got a gig doing the odd interview for TVNZ, the most memorable of which was an audience with Bobby Brown. At the end of our time, I asked Bobby whether he had a message for the fans in New Zealand.

"Yes I do," he said, and turned to look straight down the barrel of the camera. "Kids … don't do drugs." I've dined out on that one a few times.

When the chance arose to follow The Chills as they toured Europe, I quit my record store job and met the band in Amsterdam, which went about how you'd expect. I wrote an epic (and somewhat indulgent) Rip It Up account of a tour I felt lucky to be part of.

From there it was a long, cold, interesting spell of months living in a squat on the dole, trying to write a novel on my new Amstrad computer, punctuated with the odd gig subbing and proofreading for music magazines.

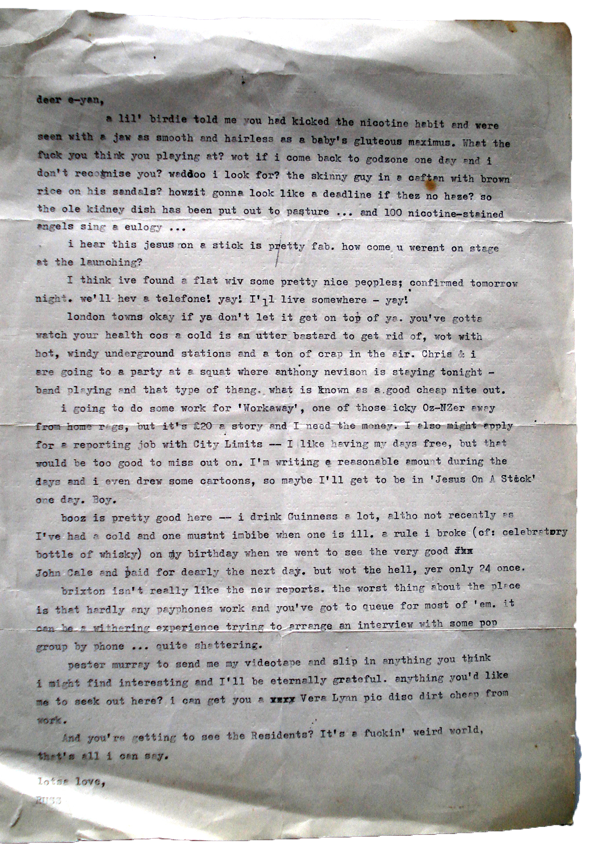

The young journalist settles into London life: an old-fashioned letter from Russell to Rip It Up designer Ian Dalziel, in 1986 - Ian Dalziel collection

In late 1987, I got another record store job, this one working out the back at the big Virgin store in Marble Arch. Richard Branson had just taken the company public, and the accountants had begun to arrive, but there was still a touch of the counter-culture about the place and the people who worked there, who nearly all seemed to be on the way to one dream or another. 1988, the year that the acid house phenomenon exploded in Britain, would be a magnificent year to be alive in London.

As much fun as working at Virgin was, when a job came up at a company called MRIB, I took it. MRIB, a descendant of the firm that compiled Britain's original music sales charts, MRIB also dabbled in publishing, and so it was that I came to write at least half of what would eventually be published as The Guinness Book of Rock Stars.

Russell Brown, on the left, backstage pre-1984 riot - Photo by Bryan Staff

Let the story be told: My writing method consisted of sitting with half a dozen other reference books open and pretty much averaging out what they said. That's how the Beach Boys and the Velvet Underground entries got written, among many others. Towards the end of the year, I fell out with the owner of the company (who was a platinum-plated prick) and resolved to spend the summer in New Zealand, where I reconnected with Rip It Up and had my brief, successful spell as a dance party promoter.

On return to London, I eventually got my first and only job on the other side of the tracks. I became press officer for the relaunched Blue Beat record label. Bad Manners frontman Buster Bloodvessel had bought rights to the legendary ska label – but not its catalogue – and was looking to develop it, and a companion heavy metal label. There were several Kiwis involved, including former Sneaky Feelings soundman Ivan Purvis.

The job offered some fascinating insights. We paid some payola to a pirate radio station to get one record listed. The father of one of the members of one of the metal bands, a picture editor at The Daily Express, helped us set up a paparazzi shot of our would-be Samantha Fox beside a cast member of Eastenders. I took our girl group up to the NME office, where they got a lot of attention.

Unfortunately, apart from writing clever press releases, I was rubbish at the job and was eventually let go. Buster eventually lost his house on the venture, and I felt bad about my small part in the whole trainwreck.

All this time, I saw a lot of The Chills and their manager Craig Taylor, who also founded Flying Nun UK and Flying Nun Europe. My closeness to the Nun scene was of interest to a number of British music journalists, who regarded the New Zealand label as a beacon of naïve musical purity. One, Simon Alexander (who wrote as Martin Aston) became a good friend.

I embraced the music papers in earnest in 1989, after Tony Stewart, once a key figure at NME and at that time editor of Sounds, turned me down for a subbing job but asked me to write regularly for the paper, where I was happy to cover hip-hop and reggae and leave the rest of the stable to fight over the latest indie band.

Tall stories at a function: Russell Brown and then AMCOS boss Paul Rose.

I was also writing the dance music column for the Rough Trade magazine, The Catalogue, which was edited by the lovely Richard Boon, who had been the Buzzcocks' first manager. On one memorable occasion, I got an advance copy of The KLF's The Ambient Album via The Catalogue and gave it a ho-hum review in Sounds. Bill Drummond, who had set up a review with a friendly hack, was furious and, I gather, promised to do me bodily harm if we ever met. We didn't, fortunately.

When Tony moved on to a new project, Select magazine, I went there too. I got some great jobs: Interviewing Deiter Meier of Yello in Poland, chasing MC Hammer through the American South. And there were some interesting people in the mix, not the least of them a friendly young Irish bloke called Graham Linehan, who would, of course, go on to create Father Ted.

But I never really thought I fitted in. Some of the star journalists seemed to me to be former public schoolboys with a surprisingly distant relationship to the reality of being in a band – most of them had never helped their mate's band pack out at the end of an evening, put it that way – or even just going out and being part of the whole, mad scene. Julie Burchill's line about the sadness of 40 year-old men enthusing over this week's 7-inch came to mind.

Murray Cammick and Russell Brown

Ironically, when we returned to New Zealand, Chris Bourke steered me into the job of writing the NZ Listener's rock column; the one that had made me think all those years ago that writing about music looked like a good thing. But the role I really enjoyed was editing Planet magazine, where music was a key part of the mix, in the sense that it had been at The Face and iD, two London magazines I regarded as inspirational. Among other things, I have fond memories of going out to South Auckland to interview the late Phil Fuemana. He symbolised a change – the flood of clever brown kids into the central city – that really interested me.

But the arrival of another baby and the harsh reality that music journalism was no way for a grown man to feed a family saw me move on. With a week's break, I stepped down as the NZ Listener's rock columnist and stepped up as the same magazine's computers columnist. The hugely powerful role that the internet has played in my life began then.

The internet changed everything. We often talk about the havoc it wrought on the music business, but the toll it took on the music press was far greater. Sounds and Melody Maker are no more. Select was flicked around a few publishers before folding. The dad-rock boom of mags like Q eventually subsided.

Russell Brown and Flying Nun's Roger Shepherd at the 1994 Big Day Out

That's not to say music journalism is dead. There will always be a role for close listeners like Gary Steel, Graham Reid and Nick Bollinger, historians like Chris Bourke and feature writers like Duncan Greive, who can connect popular music to the wider culture. For the likes of Grant Smithies, for whom DJing and writing are complementary skills, and for musicians who write like Peter McLennan and street-level talent-spotters like Martyn Pepperell. But the music press as we knew it? Nah.

(NB: There aren't any women in that list, I know, it's an issue. I worked with some great female photographers, but the heyday of Julie Burchill and Caroline Coon apart, music journalism is mostly a sausagefest. Go figure)

In part, the music press fell prey to the same issues as the rest of the print world; advertising ebbed, and the attention of the audience was swallowed up by a hundred other distractions. But there was something else. The musicians didn't need us any more.

In New York in 1989, to interview Youssou N’Dour for Select magazine

Artists now can and do connect directly with fans, unmediated by the papers. And the fans don't need music journalists to tell them what's hip, because it's now within their power to say what's hip. They don't have to take a punt on an expensive imported record, or shell out for a CD – it's all just there to try.

NME has survived as a web publication (I wouldn't expect it to be in print for much longer), and the likes of Pitchfork have further adapted its tradition for the internet. But I'm really more interested in MP3 blogs, which focus more on being first with the tunes rather than pontificating on them. When they're aggregated by sites like The Hype Machine, they're really more like the record stores in London, where we'd clamour at the counter to hear each new platter as it was fished out of the courier pack. We don't have to wait three months to find out what's cool.

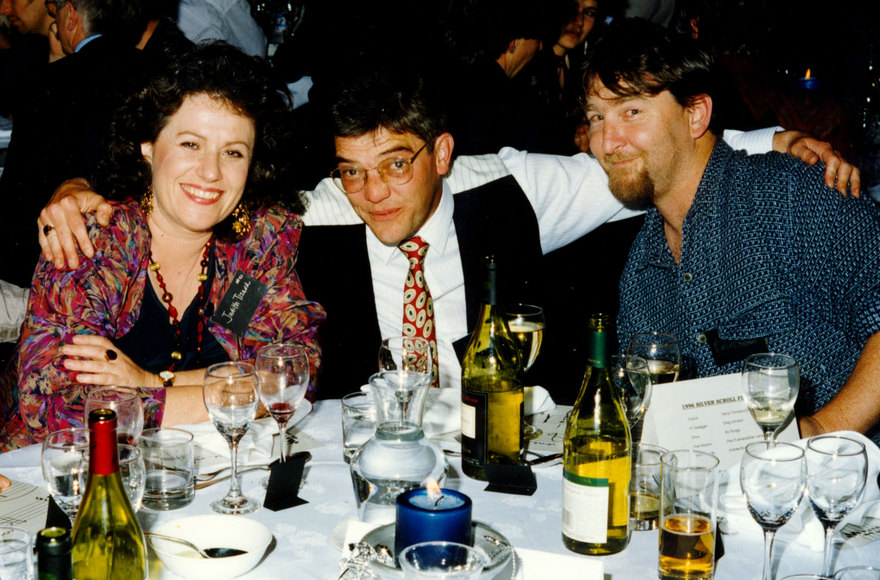

MP and future Associate Minister of the Arts, Judith Tizard, Paul Rose and Russell Brown, 1996

I have a great deal of respect for current local music blogs like The Corner, Cheese on Toast and Under the Radar. They're authentically part of the scenes they cover, part of the ecosystem. But I don't feel the need to be arch any more. When I run into musicians whose bands I used to castigate in the old days, it just feels silly now.

In recent years, the internet has revitalised my relationship with music, both in finding the new and rediscovering the old. My Friday music posts on my own blog tend to be a fusion of the two. New tunes from Soundcloud or TheAudience, and vintage releases to be set in context. The latter is where we grizzled music hacks – the people writing so well here on AudioCulture – have a contribution to make. It's not just having memories, but simply having a memory in a fleeting, real-time world.

There's even less of a living to be made writing about music than there once was, but, for me anyway, it's no less fun to do. Fridays are my favourite day on the blog, and I don't really care too much how many people read it. It's just the thing I can do in the culture.

Meanwhile, Rip It Up is still around and this year, under the latest of a series of owners, it will return to what it was when I first found it: a nationally-distributed free magazine. I hope some kid in 2014 finds it worth picking up and sneaking out of the shop.