The Ponsonby Club Hotel, aka The Gluepot, 1962. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 919-36

There had been a hotel on the corner of Ponsonby and Jervois Roads, also known as Three Lamps Corner, since the 1870s. A new building was erected in 1903 and again in 1939 (the final and still-existing structure). Labour Party Prime Minister Michael Savage, who lived in nearby O'Neill Street, was a regular, and its position as the last pub before hitting the dry lands of West Auckland ensured continuing popularity.

The original Ponsonby Club Hotel in the 19th Century

The Gluepot around the turn of the 20th Century

Purchased by Dominion Breweries in 1930, it was renamed the DB Ponsonby Club Hotel after it reputedly operated as club when prohibitionists objected to the hotel's renewed licence. A labyrinthine two-storey building, it served as Dominion Breweries' flagship pub for the next 64 years.

The Ponsonby Club Hotel in the early 1960s

For half a century, from 1917 to 1967, New Zealand hotels closed at 6pm (the “Six o'clock swill”) and the Ponsonby Club Hotel was supposedly nicknamed The Gluepot by disgruntled housewives whose husbands were "stuck in the glue pot". It was only after licensing restrictions finished in October 1967 that hotels such as The Gluepot began using entertainment to lure patrons.

The Radars

At the time, The Gluepot's manager was Len Pickard and the hotel's first resident band was The Radars, a quartet of sightless and near-sightless musicians, formed at the Auckland Institute For The Blind in Newmarket. A friend of the band, Northlander Eddie Cook, acted as their driver and by default he became the original Gluepot bookings manager. "I was never The Radars' manager," Cook explains, "but being blind, the band needed someone to drive them around so I just fell into the job at The Gluepot."

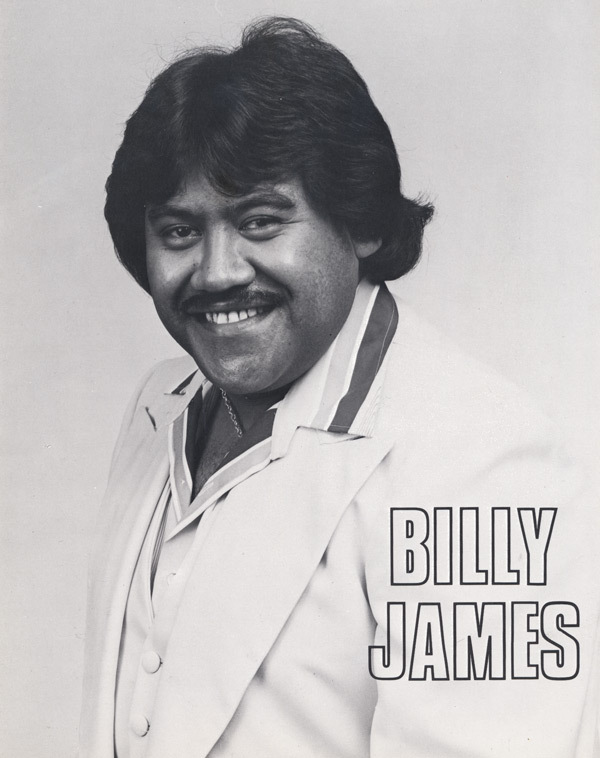

A pre-TV fame Billy T. James, around the time he was a regular performer at The Gluepot

Other groups would occasionally relieve but over the next seven years The Radars remained resident band at The Gluepot's upstairs room, backing the myriad solo attractions who performed 20-minute floorshows – Billy T. James, Rim D. Paul, George Tumahai – they occasionally moved aside to make room for Prince Tui Teka or the Maori Volcanics. They played Wednesday through to Saturday nights, plus a Saturday afternoon performance. "There were good-sized crowds every night," Cook recalls, "but on Friday and Saturday nights it was full."

In 1973 Cook was lured away to handle the bookings for the Great Northern Hotel in Queen Street but he was back at The Gluepot the following year at the behest of a new manager, Les Wilson.

Wilson was old school, viewing musicians as casual employees, no different to the bar staff and cleaners. He could be a fuddy-duddy. Cook: "Les would inspect the stage for damage every morning and if he didn't like the band's repertoire or attitude, he'd soon let me know!"

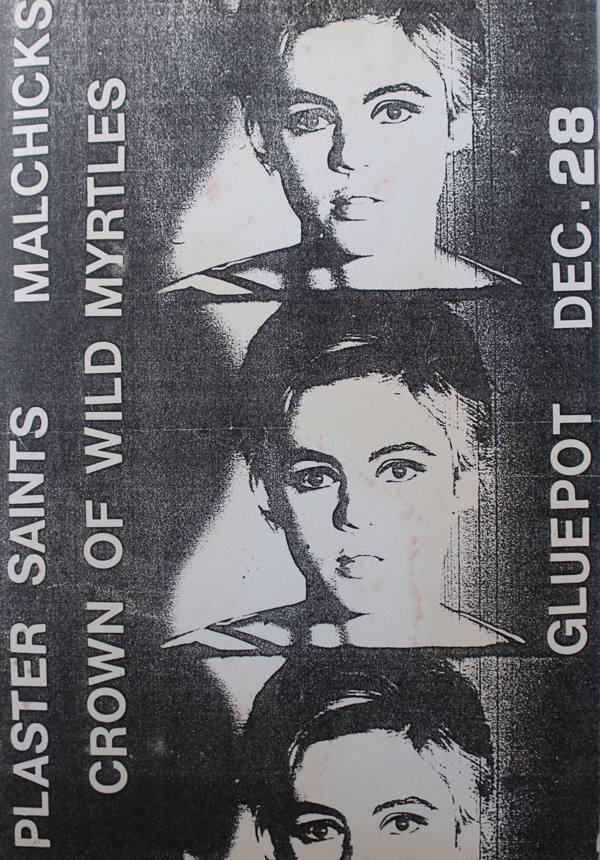

When The Radars' sojourn came to an end in 1976, similar-styled bands replaced them, mostly Māori acts playing covers, proficient enough to back those solo acts. That all changed in December 1977 when Hello Sailor manager David Gapes approached Cook and Wilson.

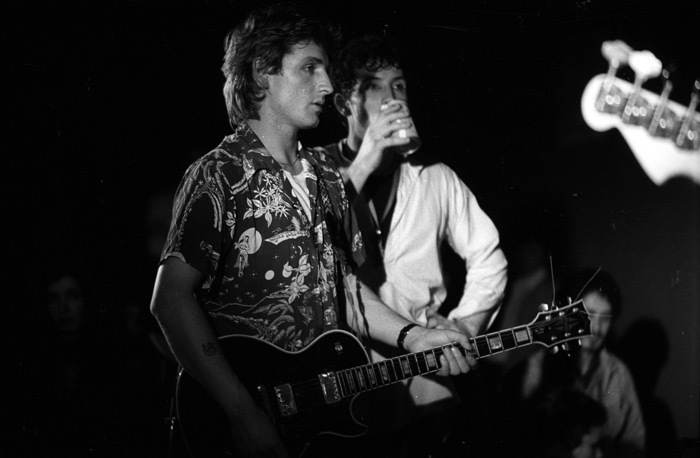

Dave McArtney and Graham Brazier, Hello Sailor, 1979 - Photo by Murray Cammick

"Les was very sceptical," Cook remembers. "He was concerned that they were a pākehā band and wouldn't appeal to our clientele and he scoffed at Dave Gapes' prediction that they would fill the room. Les said to me, 'If they fill the room I'll buy those boys beer all night!' " They filled the room three nights in a row.

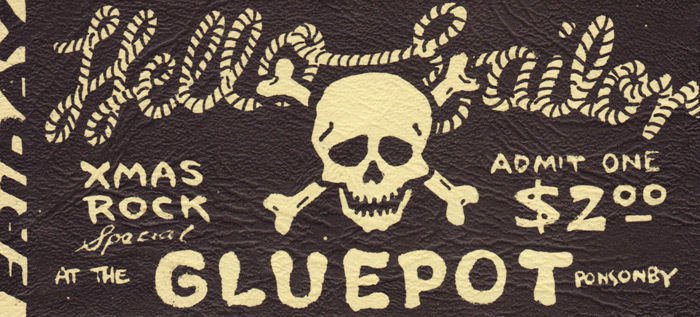

Hello Sailor's Xmas 1977 party

Cook remembers the first Sailor performance. "On the first night, a Thursday I think, the Gluepot carpark was full – I'd never seen it full before and, of course, in the pub ... man, they couldn't fit any more in."

Sailor's success prompted a change in The Gluepot's musical policy. Out went the Māori showbands and in came Citizen Band, Th' Dudes, Mi-Sex, Rough Justice, Street Talk … rock and roll! With its 600-capacity size (much abused in the early years) The Gluepot rapidly became Auckland's premier gig.

By mid-1978 Cook had introduced Monday to Wednesday entertainment featuring up-and-coming acts. Two local Ponsonby acts, The Sam Ford Verandah Band and the Topp Twins, kick-started their careers with early-week performances at The Gluepot. And then there was Robman & Brian Up The Bloody Gluepot, based on two Radio Hauraki comedy characters (Ian Watkin and Derek Payne), featuring Spats and the Limbs Dance Company. The show filled the room three nights in a row.

Assorted bands that trode the stage upstairs at The Gluepot, circa 1985. Amongst the faces are Hello Sailor, The Neighbours, Tommy Fergusson, promoter Mike Corless, Beaver, Josie Rika, Hattie St. John, Hammond Gamble, Hello Sailor's former manager David Gapes, Rick Bryant, Trudi Green and Sam Ford of The Neighbours, Neil Edwards, booker Eddie Cook, the daunting door minder Phyllis (next to Tommy – 3rd from right).

In 1979 there were structural changes to the upstairs bar with a backstage dressing room, improved sight lines and a higher stage. In August the gangly and energetic Peter Garrett, fronting Aussie hard rockers Midnight Oil, put his foot through the new stage. Wilson, known to moan about bands leaving gaffer tape stuck to the stage, was irate.

Meanwhile in the public bar ... - Photo by Max Oettli. National Library of New Zealand

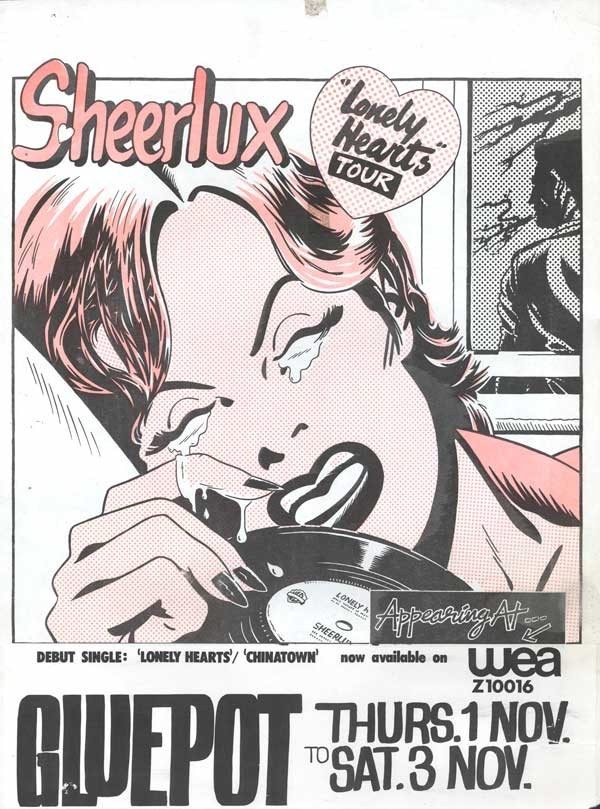

Sheerlux at The Gluepot, November 1979

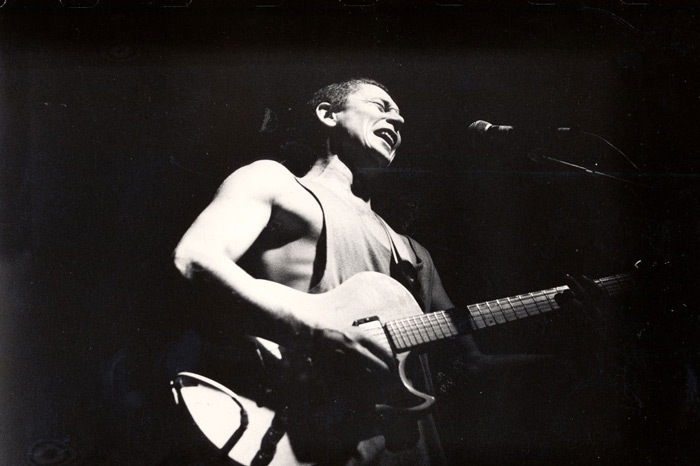

When The Enemy played The Gluepot in 1978, Chris Knox slashed his arms with a broken bottle and wandered among the small crowd displaying his wounds. Wilson and Cook were horrified and the band was banished. Twelve months later, having morphed into the major drawcard Toy Love, Cook nervously allowed them back and was disconcerted to see drummer Mike Dooley arrive wearing hobnail boots, disallowed under Wilson's prescribed dress code. Cook convinced Dooley to take off his boots before entering, stressing "and do not wear them on stage". Dooley was bemused but he didn't have to deal with Les Wilson.

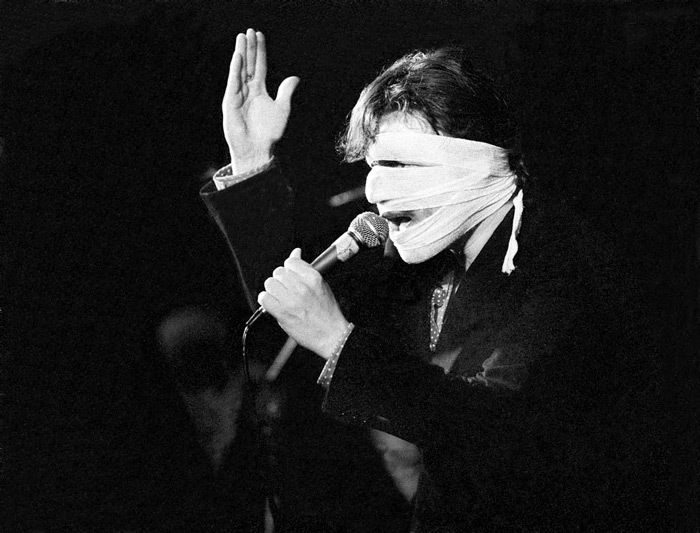

Chris Knox with Toy Love at The Gluepot, 1980 - Photo by Anthony Phelps

Wilson made no pretence of knowledge about the music industry but he knew that he was onto a goldmine and he just loved Hammond Gamble from the moment he saw him helping staff clear the tables after a Street Talk gig, not to mention Street Talk establishing the all-time record for a bar take – over 6000 drinks served. Not a big fan of drinks riders, Wilson made an exception with Gamble and others who packed the place. When the popular Ladies Sing The Blues revue played The Gluepot, he placed flowers and chilled champagne in the dressing room.

The Screaming Meemees, late 1982 after a gig - Photo by Michael Thompson

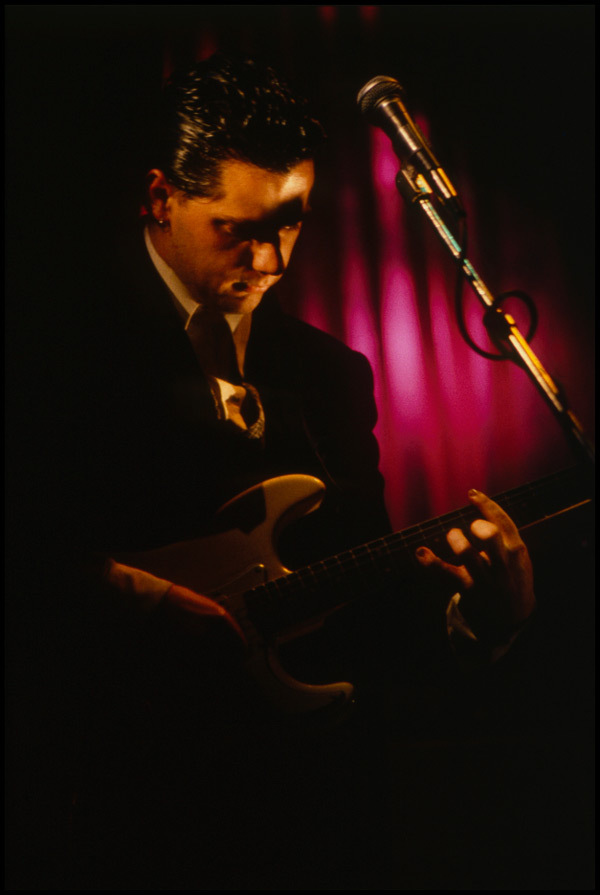

Rick Bryant at The Gluepot, 1985 - Photo by Jonathan Ganley

Other successes, notably the one-off gig by Rick Bryant's Jive Bombers, turned into regular events and, indeed, prompted Bryant to depart his existing band, The Neighbours, and concentrate on the Jive Bombers as a permanent unit.

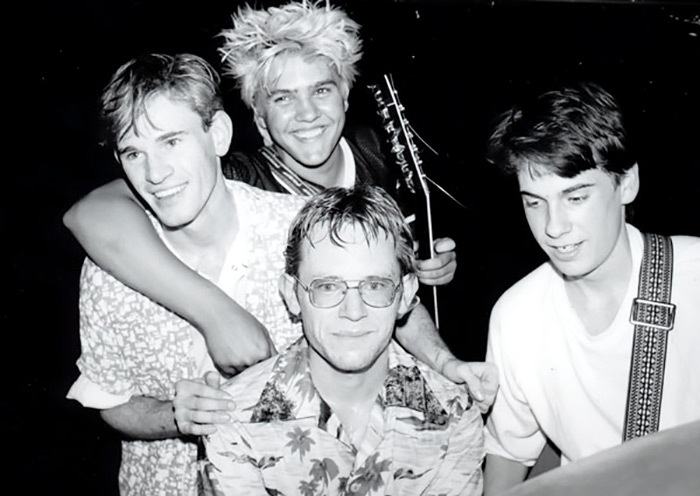

Jordan Luck and The Dance Exponents on their first dates in Auckland, mid-1982 - Photo by Karen Stevens

Outside promoters began using The Gluepot. Charley Gray presented American jazzman Sam Rivers and, starting with John Cale in 1983, Doug Hood of Looney Tours presented Paul Kelly, Nico, the Hoodoo Gurus, Hunters & Collectors and others. The house record, though, was set by New Zealand's The Chills, managed by Hood, who reputedly doubled the legal capacity with a crowd of 1200.

US jazzman Joe Henderson with Frank Gibson Jr. behind, mid-1980s

One promoter who found the Gluepot a perfect fit was Real Groovy Records' Kevin Byrt – Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Billie Joe Shaver and Lucinda Williams all played The Gluepot. Another Real Groovy promotion, Warren Zevon's 1992 Gluepot performance, was recorded and two tracks subsequently featured on Zevon's Learning To Flinch live album.

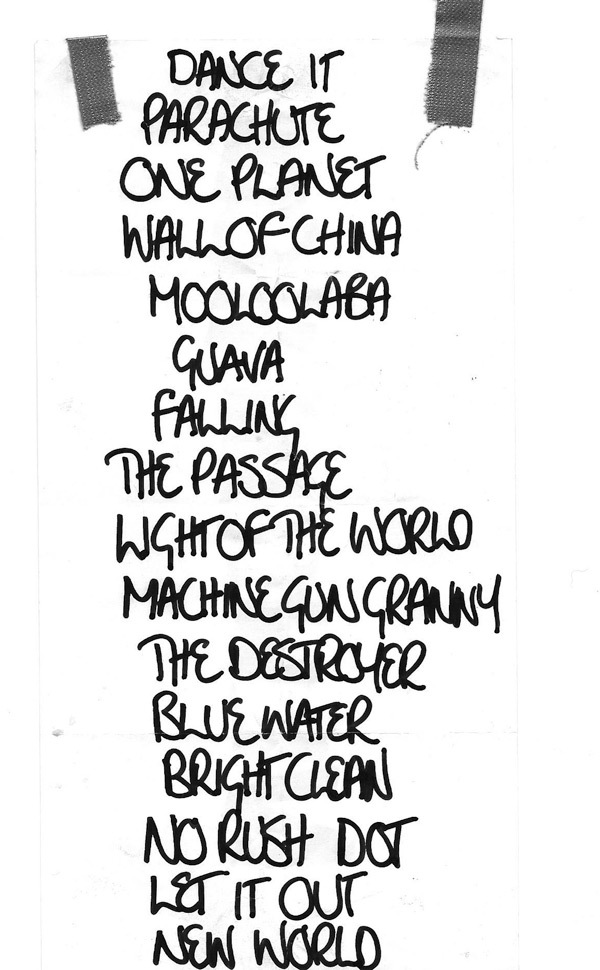

Big Sideways set list, circa 1983 - Mark Everton collection

There were other international acts – dismal turnouts for Kinky Friedman and Loudon Wainwright III (he was nothing short of brilliant and totally hilarious) but a well-deserved full house for John Prine, possibly my all-time favourite Gluepot performance. Toots & The Maytals left the stage to one of the happiest audiences I've ever been a part of.

In November 1988 a group billed as The Sons Of Sodom was none other than Mick Jagger and band, in town to perform at Western Springs Stadium later in the week. A promo arranged by Radio Hauraki and promoter Hugh Lynn, Jagger delivered a 30-minute set. Mick Jagger! The Gluepot had become an institution.

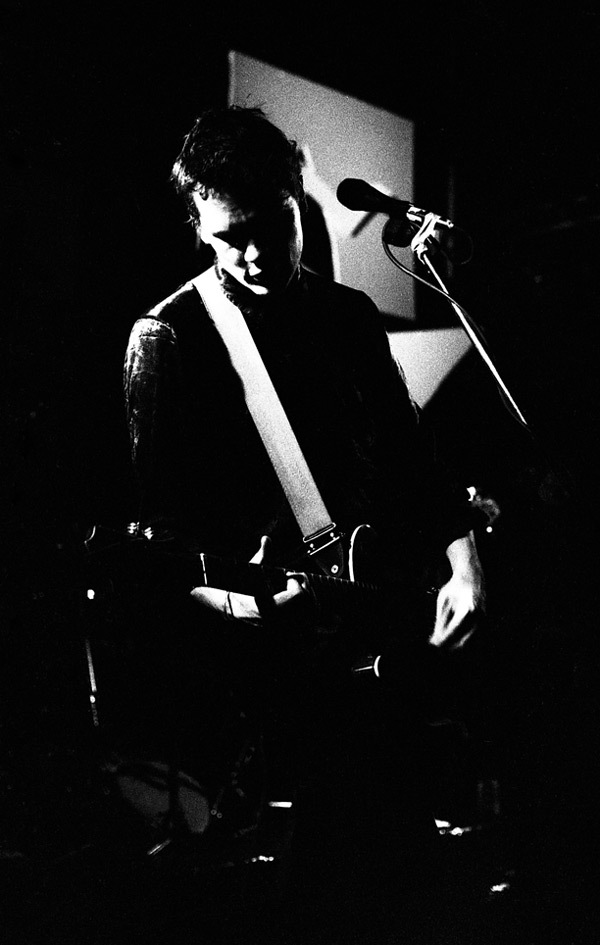

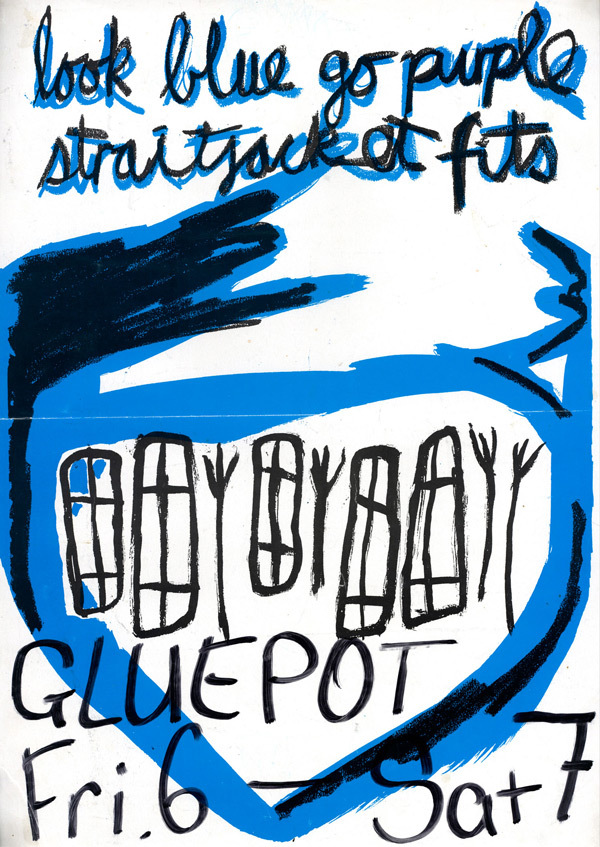

Shayne Carter with Straitjacket Fits, 1987 - Photo by Jonathan Ganley

By that stage, there had been several changes, not least being the departure of Cook and Wilson. In 1985 the hotel had extensive renovations, the main room reopening with reformations by Hello Sailor and Street Talk. Shortly after, Dominion Breweries replaced Wilson and, as was to become customary, with the hotel manager went the bookings manager. Eddie Cook was out and Paul Walker was in.

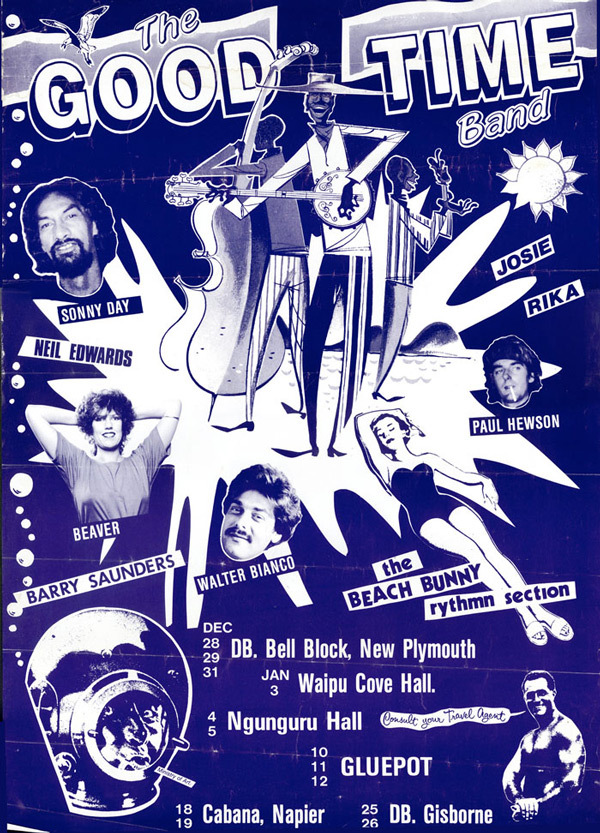

Eddie Cook had never been a fulltime Gluepot employee, always retaining a nine to five job in the building industry, and Paul Walker had been assisting Cook since 1981. As a promoter, Walker had been responsible for some of the Gluepot's most successful events, notably the All-Stars Play The Blues revue, featuring Walker's wife Beaver, Sonny Day, Midge Marsden, Mike Farrell and others. The All-Stars also provided backing for visiting performers from across the Tasman, including Renee Geyer and Marc Hunter.

In 1985 Dominion Breweries advertised for a bookings manager. Walker, already responsible for the duties required, had to attend an interview. "I remember being asked me why I thought I was suitable for the position. I said The Gluepot was my local pub and that, I think, was what got me the job."

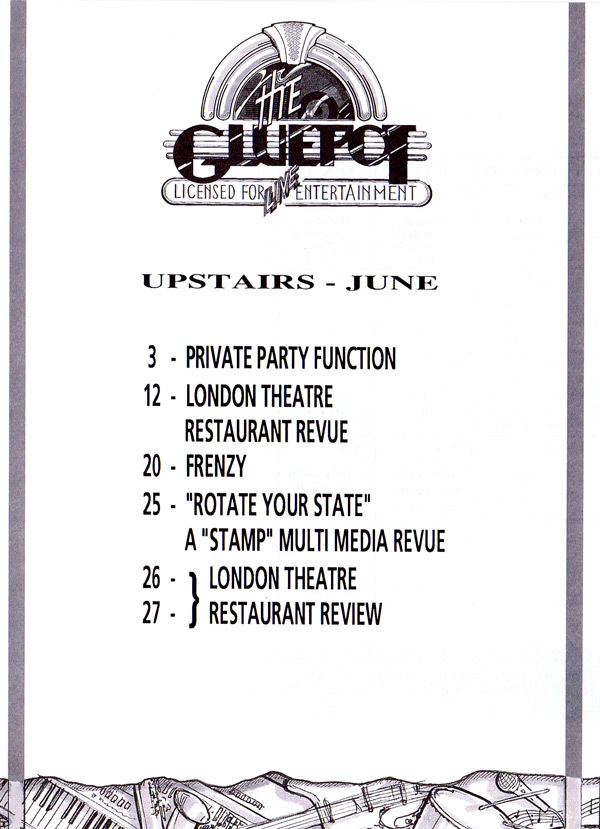

Walker inherited a new setup, featuring music in two bars. The Corner Bar had arrived, featuring free live entertainment from Thursday to Saturday; in time this would extend to seven nights a week, plus weekend afternoons. Bands like Cheek Ta Cheek made their name in this smaller bar while other regulars included Truda Chadwick, the solo Sailors, Sonny Day and smaller Rick Bryant outfits. Dennis Mason's 358's was named in reference to The Gluepot's street number.

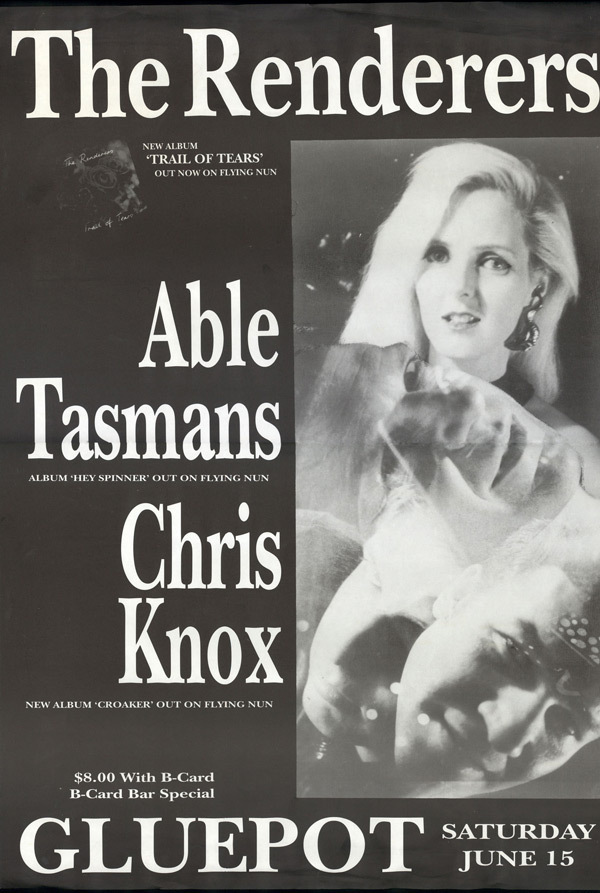

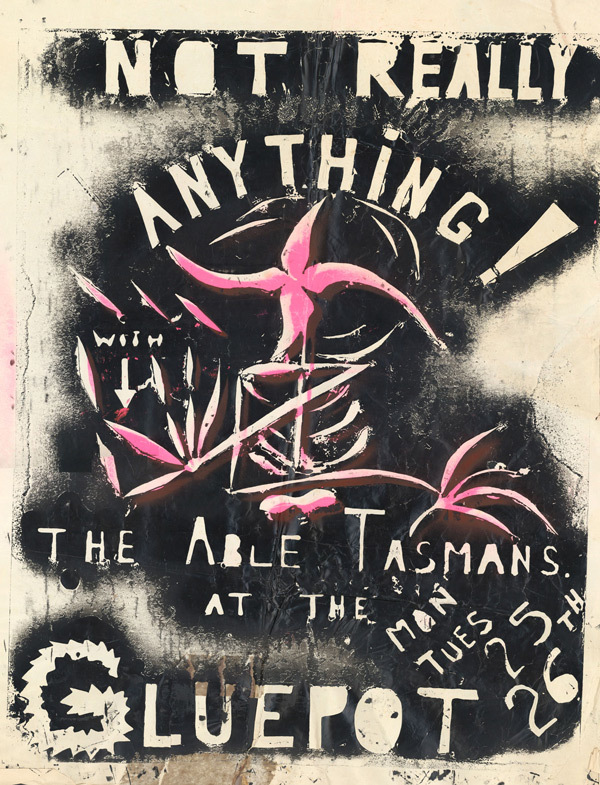

Graeme Humphreys at the Gluepot with the Able Tasmans, year unknown

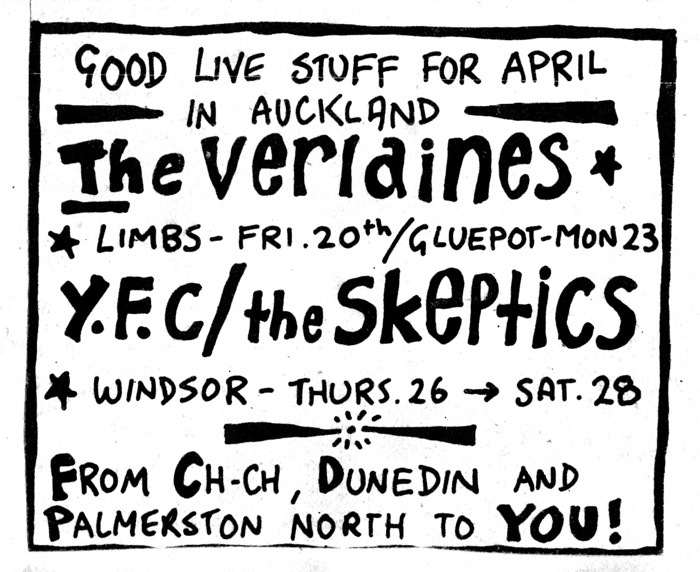

Meanwhile, the music in the main room at times differed little from that available for free downstairs. Promoters Kevin Byrt and Doug Hood continued using the room but in-house promotions tended to reflect Walker's personal tastes.

Walker: "The musos who made up the All-Stars were all in other bands and not particularly big-drawing bands either but as the All-Stars they performed to much larger crowds and received a decent paypacket too."

Peter Gutteridge at The Gluepot with Snapper, around 1988/89 - Photo by Jonathan Ganley

In 1989 Walker left The Gluepot when he became co-owner of Ponsonby venue the Java Jive. Sharon McNabb, whose personal tastes ran to the more alternative, replaced him. Between Les Wilson's departure in 1985 and the closure of The Gluepot in 1994, no fewer than nine managers passed through the hotel, each with their own ideas on how the place should be run. The longest-serving of these, Andy Giles, was a genuine NZ music fan; one short-lived manager left under a cloud after he was pulled up on the Auckland Harbour Bridge with a cache of illegal firearms.

The Scissormen's John Kempt and Tony Lumsden, circa 1990 - Photo by Graham Hooper. John Kempt collection

Another, a narrow-minded former Air Force officer, arrived from some outback pub in the South Island and didn't have a clue about dealing with musicians or the predominantly Polynesian clientele in the Vista (public) Bar. One evening in the Corner Bar he asked me to spread the word that Truda Chadwick would be kicking off the early-week Corner Bar entertainment. "I'd really like to see big crowds for the first week, even if we have to rely on those Polos next door." He didn't last long.

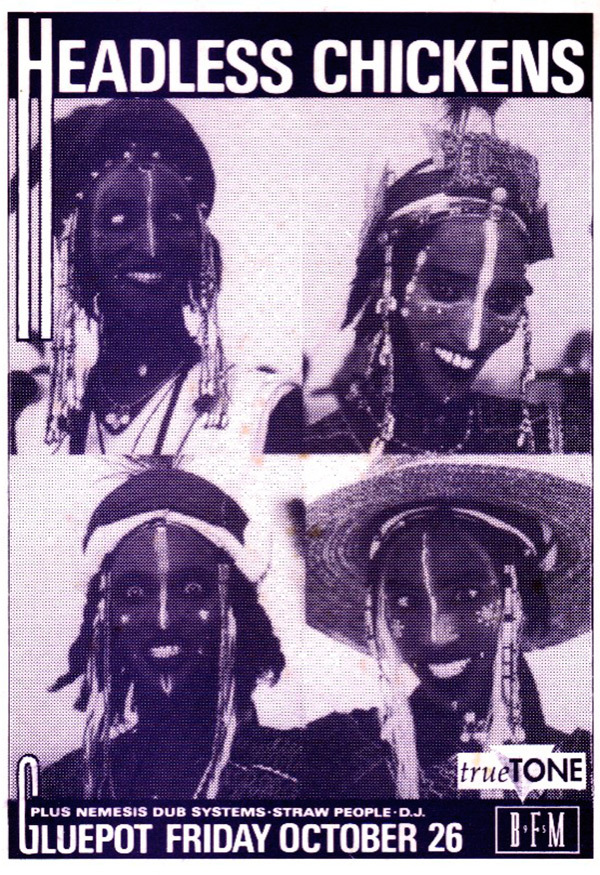

Chris Matthews with the Headless Chickens, 1987 - Photo by Jonathan Ganley

As managers came and went, so too did the bookings managers. Walker was replaced by Poss Cameron and then came Andy Cave. Walker returned for a second stint, followed by Sharon McNabb and, finally, Tommy Adderley and Rodger Fox. The last Gluepot manager, Michael Woodham, dispensed with a bookings manager to handle it himself.

In the midst of all this, there was a bizarre upgrade of the Corner Bar, which incorporated an attempt at a NZ music hall of fame, glass cases featuring music memorabilia. Billy Kristian considerately loaned his prototype Wyman bass guitar, given to him by Rolling Stone Bill Wyman in 1965, and Tom Sharplin donated a prosthetic leg, which protruded from the ceiling above the bar. The mural covering the walls missed the point though. The out-of-town outfit that did it, competent enough artists, mistook Ponsonby Road for Karangahape Road, complete with streetwalkers.

In its final years The Gluepot added live music to the Vista Bar (Sonny Day was king) from Thursday to Saturday. With three rooms of live entertainment, The Gluepot truly was NZ's premier music venue. Meanwhile, upstairs the big acts just kept a-coming. Bob Mould, Screaming Jay Hawkins, Ted Hawkins, Judy Mowatt, Tom Russell, Junior Wells …

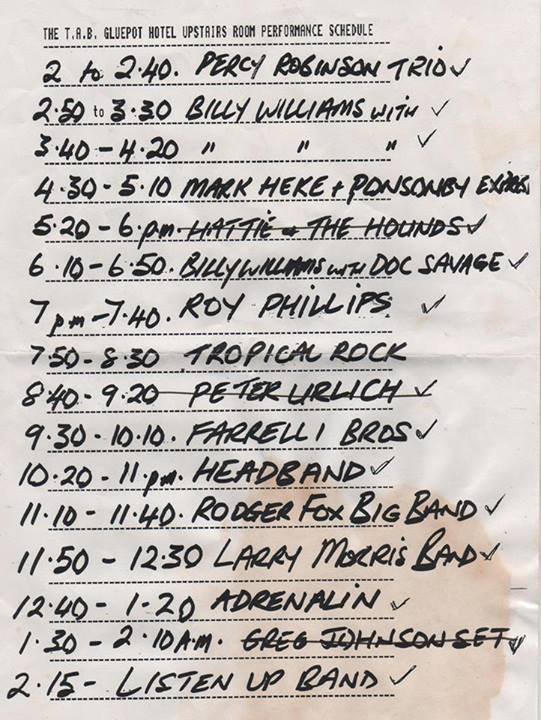

The Tommy Adderley farewell gig lineup, 11 April 1993

And not just upstairs either – in 1993 the Corner Bar began presenting name performers, including Dave Van Ronk, Jimmy La Favre and Georgie Fame. A solo performance by Tim Finn, songs stripped back, remains another of my favourite Gluepot gigs.

With three live music bars, Russell Goodmanson's Live Sound secured the contract to provide production. "Throughout the 1970s we always had an in-house PA,” remembers Eddie Cook, “but that rapidly became too small."

During the 1970s The Gluepot employed over 40 full-time staff but it was half that by the 1990s, the slack taken up by casual workers. Some staff became as familiar as the furniture. Receptionist Sheila Lowe spent over 40 years employed by Dominion Breweries, 29 years of them at the Gluepot. At the time of its closure, assistant manager Wally Jarvis had been at the Gluepot three months shy of a quarter-century. And then there was Phyllis.

Phyllis Gall became the face of The Gluepot. Seated at the top of the stairs in her familiar tracksuit, no one got past Phyllis. No press pass, no amount of stature in the music community and no friend of staff could get past Phyllis unless your name was written on the guest list, no exceptions. As one Ponsonby musician and Gluepot regular mused recently, "Just getting to the Gluepot could be an adventure but getting past Phyllis at the door was something else."

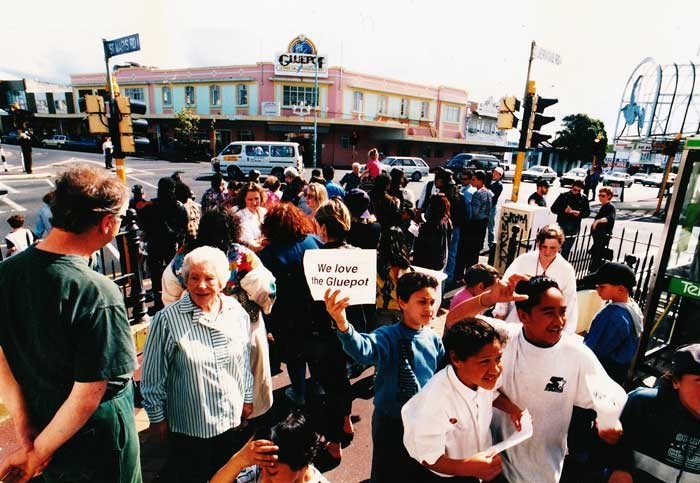

A Save The Gluepot protest. To the left, in green, is drummer Jim Lawrie and in front of him is the Gluepot's chef, Pat Maxwell - Jim Lawrie collection

In 1994, after months of rumours and speculation, Dominion Breweries announced that The Gluepot was to be sold. A Save The Gluepot campaign began, petitions were circulated, and public meetings attracted hundreds, but all to no avail. Times had changed, Ponsonby had changed, and the once low-rent suburb with overcrowded streets, houses just a metre apart, had become one of Auckland's trendiest neighbourhoods.

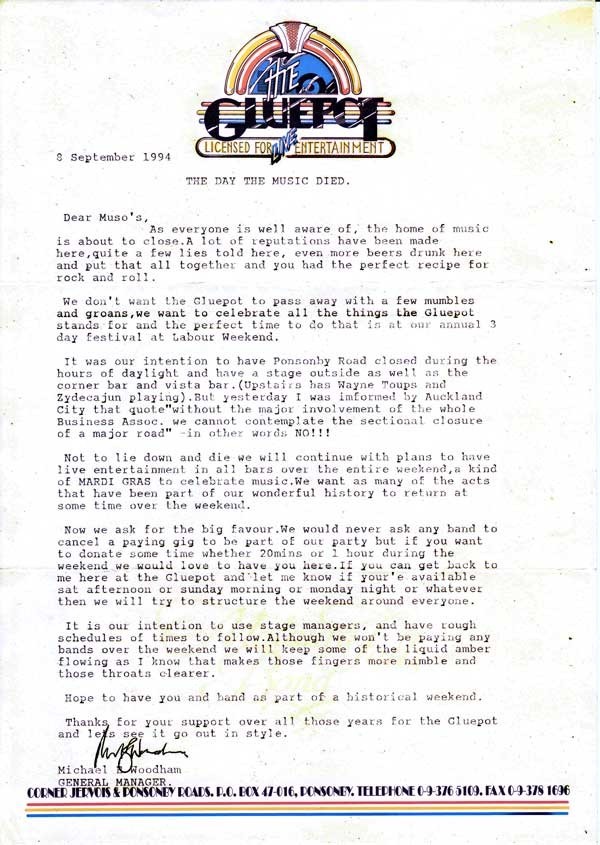

A final letter to the Gluepot bands – asking them to play just one more time for a beer. - Michael Woodham collection. Courtesy of Glen Moffatt.

The final week featured a star-studded line-up, culminating in live entertainment in all three bars over the Labour Day Weekend. Referring to the Save The Gluepot campaign, Dave Dobbyn said from the stage, "Get over it, it's just a building." To the Vista Bar patrons, the old pre-Yuppie clientele, it was much more than "just a building". It was the community's marae, and one segment of the Vista Bar felt particularly aggrieved. On the Saturday night, 48 hours before its scheduled closure, the King Cobra street gang ran amok, trashing the Vista Bar. The other two bars closed on Labour Day Monday, 24 October 1994.

In 1994, just weeks after The Gluepot was closed, I came across a German tourist taking photographs of the building. She explained to me, "Back home I only knew two things about New Zealand music – Split Enz and the Gluepot."

--

Read more: Rick Bryant pays tribute to The Gluepot

Watch: Gluepot reunion documentary, by Steven Orsbourn