Everyone can tell a story about themselves or their family members learning music, performing, listening to the radio, buying that 45, or going to a local dance. The odds are that during the 1960s your life was touched by a Māori musician or performer.

I pay homage to all of the Māori musicians of the Māori showband movement who have paved the way for the Māori and Pasifika artists and entertainers of today. Most especially to my dad, who passed away when I was 10. I couldn’t get all the stories from him back then, but I collect them now from people who knew him. The showbands may not have made their members fortunes, but we are fortunate to have their musical memories with us to keep alive.

Kewene family hangi, 1977. Louise is being held; her father Heke is at right. - Louise Kewene-Doig Collection

The Māori showbands were a musical phenomenon, featuring great entertainers and, above all, incredible musicians. “Māori showbands” is the term I use to describe over 80 individual performers and groups that spanned the 1950s to the 1980s as a whānau. These talented individuals formed ensembles – usually comprising one female and six males – that found success all over the world, but were perhaps less recognised here in New Zealand.

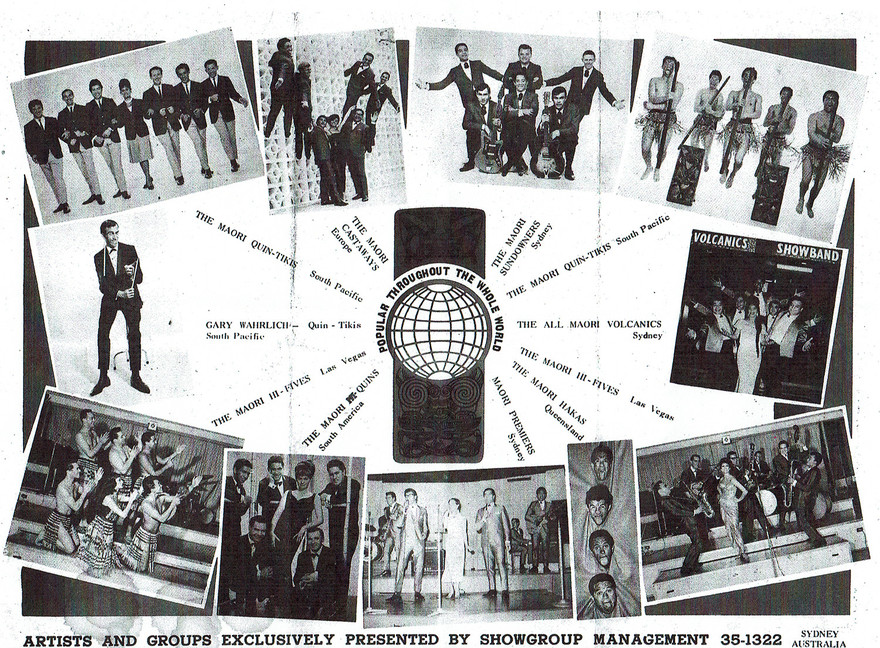

While stars such as Sir Howard Morrison, Billy T James and groups like the Māori Volcanics and Rim D Paul and the Quin Tikis might be household names, many others are not so well known. Among them are The Māori Castaways, The Māori Troubadours, The Brown Bombers, The Tai Paul Band, the Māori Hi-Five.

Yet these acts, too, glittered, danced and entertained their way around the globe in the 1960s: the heyday of the Māori showband phenomenon. They toured the world, enjoyed residencies in places ranging from the Bahamas to Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, and played for New Zealand and Australian troops during the Vietnam War. Simply, there weren’t many places and faces the Māori showbands didn’t touch.

The Quin Tikis in Vietnam: Weasel Tairoa, Gary Wahrlich, Kevin Rongonui, Freddy Summers, Keri Summers, Sam Mateparae

The showbands had a unique ability to blend entertainment, performance and musicianship, together with being Māori. They rehearsed over and over and over again until their performances were flawless. If you didn’t give a perfect performance or didn’t smile enough, your manager could and would dock your wages. There are stories of acts rocking up to a venue in their £300 suits looking really flash and then after the show having to split a pie between them. It was a musical movement that didn’t make them rich, but turned them into highly professional performers.

Although I can only experience Māori showbands through images, photos, records, stories and movies, I have spent the past five years researching my dad’s place in the showband world, so let’s start off by saying that this piece is not a timeline, nor a blow-by-blow account of every single Māori musician or group who performed their way around the globe. I would need a whole book for that. Rather, this is a daughter’s account.

My dad was Hekemaru Kewene (Waikato and Ngāti Maniapoto) of Kiwi Esplanade, Māngere Bridge – our whānau having moved to Auckland from sleepy Kāwhia in the 1950s in search of work. (As a side note, Kiwi Esplanade was named after my grandmother Ani Paki. My Aunty Mabel explains: “The road was put through to be formed and it ended at our front gate, and the Council approached my parents to ask what it should be called since they were the only home actually on the beach front. My mother’s name [is] Ann Louise and [her nickname is] Kiwi, and Dad having a little bit of ingenuity said this road runs round the beach, why don’t we call it Esplanade? And so Kiwi Esplanade it was named, and it extended from the Bridge to our front gate.”)

Dad learned piano and singing from Sister Mary Leo, who later taught Kiri Te Kanawa.

Dad’s mum, Ani, played the flute, and his siblings and cousins were musical as well. Dad learned classical piano and singing from the famous Dame Sister Mary Leo, who later taught Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, and became head of music at St Mary’s College.

Dad told stories to us of having to row over the harbour to school before the Māngere Bridge was built. I don’t know how much truth there was in this story, but it sounded a lot of fun at the time. He came from a large family that loved music and was loved by music. He played piano and recorded for groups and bands around Auckland city, taught music at St Stephen’s Māori College, and also sang opera.

He was playing and recording with the likes of his Samoan friends’ band, The Keil Isles, to singing with the Latter-Day Saints Māori Choir, to playing with his group The Playdates at the Picasso coffee lounge or at the Māori Community Centre. At these and other Auckland venues he performed with many groups until he was called in to be part of The Māori Hi-Five (third incarnation) with his mate Danny Robinson.

Now for the confusing part: there were actually three Māori Hi-Five bands. Each band configuration was known as (1), (2) or (3), but with roman numerals on their costumes. The first version of The Māori Hi-Five – and the most famous – featured Wes Epae, King Solomon (Solly) Pōhatu, Robert Hemi, Paddy Te Tai, Kawana Pohe and Peter Wolland. Female singers Rena Pohe and Hiria Moffat were also part of The Māori Hi-Five (1) at different times in their musical history. Mary McMullen (née Nimmo), however, was the group’s longest-serving female singer. This promotional photograph was taken when the group had a residency at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas in the late Sixties.

The Māori Hi-Five at Caesars Palace, Las Vegas, late 1960s. Back row, from left: Paddy Te Tai, Mary Nimmo-McMullan, Peter Wolland, Wes Epae, Rob Hemi. In front, Kawana Pohe and Solomon Pōhatu. - Louise Kewene-Doig Collection

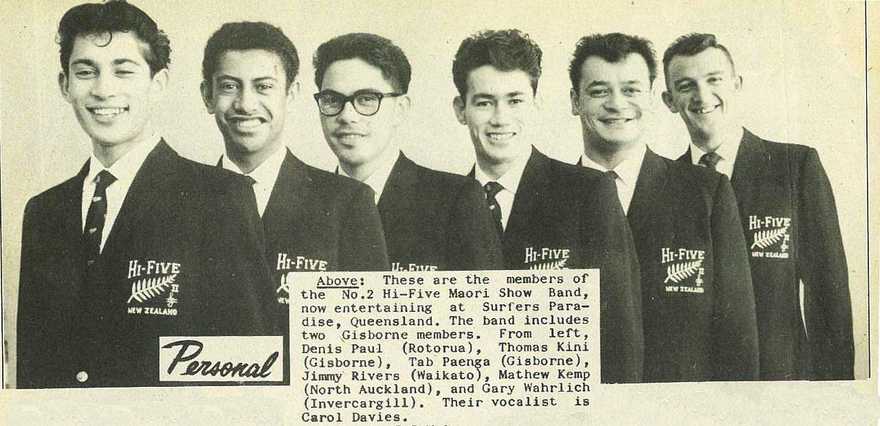

The second version of The Māori Hi-Five was Rim D Paul, Thomas Kini, Tab Paenga, Jimmy Rivers, Mathew Kemp and Gary Wahrlich. By the time the group got to Australia, they would be known as The Hi-Quins. This photograph was taken shortly before the group departed for Surfers Paradise in June of 1960. Vocalist Mary McMullen joined the group in Australia.

The No. 2 Māori Hi-Five showband at Surfers Paradise. From left, Denis Paul (Rotorua), Thomas Kini (Gisborne), Tab Paenga (Gisborne), Jimmy Rivers (Waikato), Mathew Kemp (North Auckland), and Gary Wahrlich (Invercargill). - Gisborne Photo News, 14 July 1960

All of the Māori Hi-Five groups were identically outfitted, and the pocket emblems on their blazers featured a fern, a musical clef, and the number of the band configuration in roman numerals: I, II or III.

Heke Kewene's Māori Hi-Five (3) blazer pocket monogram. - Louise Kewene-Doig collection

The Hi-Quins flew from Sydney to England, taking over from The Hi-Five (1), who had a residency at the Pigalle Restaurant residency in Piccadilly but were heading off to start their tour of the United States.

By this time The Hi Quins had gained and lost members. Lynn Rogers was now singing for them, and the band members were Eddie Nuku, Thomas Kini, Kawana Waitere, Junior Rivers, Rim D. Paul and drummer Neville Turner.

Rim D Paul left The Hi Quins in 1963 to join The Quin Tikis, and the band was renamed Rim D Paul and the Quin Tikis (this line-up included the wonderful vocal stylings of Keri Northover, née Summers). Rim D Paul and the Quin Tikis were invited to provide the musical background and comic relief in the 1966 John O’Shea movie Don’t Let It Get You. The Quin Tikis provided their musical talent as well as a showcase for Māori showband musicianship and skills alongside Rim D Paul, Sir Howard Morrison and Dame Kiri Te Kanawa. It was the Quin Tikis’ talent that stole the limelight, though.

The Māori Hi-Five bands were put together by the management team of Charles Mather and Jim Anderson. Anderson had this grand idea of branding at least five bands as The Māori Hi-Five. He wanted the groups to follow on from each other, one after the other around the world, ending with a giant performing spectacular to be held in London. Unfortunately, that dream dissipated with only three incarnations of the group making it offshore.

Māori showbands represented by the Showgroup Management agency. - Louise Kewene-Doig collection

The Māori Hi-Five (1) came back to New Zealand for a short tour, but New Zealand audiences weren’t ready for the polished international act they had become. The tour met with poor attendance. A reason for this may have been that the New Zealand audiences were not familiar with their music as much as overseas audiences were.

The Māori Hi-Five (3) – my dad’s band – flew to Australia to take up residency playing gigs on the Gold Coast, Brisbane and Sydney. During their time in Australia, the group collected the very talented Jennifer Dachroden (née Warner) on vocals. They now had the traditional Māori showband line-up: guitars, bass, drums, piano/keyboards, horn section/brass/woodwind, male vocals, and female vocals.

The photo taken at the Chevron Hotel is one of their Christmas postcards from 1963/1964. Jennifer was a smart woman and could see the lay of the land with manager Anderson. By this time, he had some notoriety as a person of interest to the police, facts which have been well documented in Australian media. The Hi-Five (3) boys were also going to feel the sting of Anderson’s tail very soon.

Heke Kewene (left) and the Māori Hi-Five at Chevron Hotel, Queensland, c 1963-64. - Louise Kewene-Doig Collection

Needless to say, by 1964, when the boys were leaving to go further afield overseas, Jennifer decided to stay in Australia. A few of the others were angry with her for that decision, but my dad was very kind to her and kept in touch. In hindsight, it was a good decision for her to stay in Australia.

So Dad and the boys started their world tour without Jennifer, heading to the sparkly destination of Singapore in 1964. The tour was to take them to Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Sweden, France, and all over Europe and England. The members at that time were Lee Hutchings, Heke Kewene, Danny Robinson, John Doherty, Rickie James, Ritchie Russell and Ted White. They also had English female singer Sam (Charlene) during their Europe tour.

Heke Kewene and Sam (aka Charlene) Canadian. - Louise Kewene-Doig Collection

The group changed their name to the Hi Fis while in Australia, separating their branding from the Hi-Fives. They were going to tour under the Hi Fis name but there was another group in the UK called the Hi Fis so they changed their name again, this time to The Māori Castaways.

The Māori Castaways opened for the Rolling Stones in Singapore, and the Beatles in Blackpool, England. My dad said the Rolling Stones gig got “a bit crazy”. However, I heard the full version from Ted White not long ago. Originally from the UK, White was the musical director and sax player for The Māori Castaways, and is still a heavyweight in the jazz and big band world today. He has a long musical legacy, contributing to 1970s Australian LPs such as Stratusphunk (by the Bruce Clarke Quintet), and Vichyssoise (Clarke and Maryan Kenyon), and musical directing for many musical icons.

The Māori Castaways opened for the Rolling Stones in Singapore, and the Beatles in Blackpool.

White is a very sharp storyteller, recalling: “We did support for The Rolling Stones at the Badminton Hall [Singapore, 16 February 1965] … [As] we came out, the crowd attacked our limos as we were going back to the hotel and tried to turn them over. We were saved by the English military police, so much so that we asked them to come in and see our show at the Singapore Hotel.” I think describing a performance where at the end you need a military escort because people were rolling vehicles is pretty damn crazy, but also pretty damn rock’n’roll cool.

It went from crazy to heartbreaking very quickly when their manager Anderson shot through with all their wages after they played in Kuala Lumpur, leaving them abandoned in a foreign country with no money. The boys had the rest of the tour already booked, but no way to get there. Needing to travel from Kuala Lumpur to Malmö in Sweden, over 12,000 kilometres away, they secured a loan from their promoter in Kuala Lumpur, agreeing to pay the money back from the next leg of their tour. White: “We said, ‘Look, we’ve got to go to Malmö in Sweden yesterday. We’ve got to be there really quick.’ So, we had to borrow the money for the airfares to get to Malmö. When we got to Malmö, we hadn’t any money.”

Having finally arrived in Malmö, The Māori Castaways were performing seven days a week. White tells one of my favourite stories from this time: “Consequently, one Sunday we were on the road; we’d been on the road on the Friday and the Saturday, and we were starving. We went to this place for a smorgasbord, and we saw it was smorgasbord for four crowns or something like that … Anyway, we went in there, and you know the Māoris are good on the tooth – we ate the bloody lot, and the guy was devastated. So Danny Robinson and myself and Lee and Richie Russell, we played for the people in there while he went and got some more food for the smorgasbord.”

I particularly love this story, because you have these poor, starving Māori boys being who they are, but also showing manākitanga (hospitality) by giving back to their hosts, and entertaining the customers to help a fellow human out.

The Māori Castaways, 1966. From left: Ritchie Russell, Lee Hutchings, Danny Robinson, John Dougherty (drummer), Rickie James, Sam (Charlene), and Heke Kewene. - Turvey & Turvey / Louise Kewene-Doig collection

The Māori Castaways were one of the highest-paid touring acts in Britain at the time, appearing on television and performing up to seven days a week. The boys stayed at Theatrical Digs, accommodation for entertainers around the UK. This is where my mother met my dad. They met, fell in love, got married and had my eldest sister, Maria. The Māori Castaways were part of their wedding party. Management then called the group back to Australia and away everyone went back to the Gold Coast.

Australia had perhaps the highest number of Māori showband performers and entertainers at one time during the 1960s. A lot of this had to do with the fact that between 1967 and 1970 over 300,000 American troops used Australia for R&R (rest and recreation) from the Vietnam War.

The Māori musicians all knew each other, playing sport and playing music together. Whanaungatanga (belonging together as a family) was real and a part of everyday life. Australia provided a nice lifestyle, beautiful weather, beaches, fun, and money for doing what they loved; something New Zealand at the time couldn’t offer them.

The Māori musicians all knew and socialised with each other. Whanaungatanga was real and a part of everyday life.

Venues rose and disappeared like waves in the ocean in the ever-changing landscape of the Gold Coast. Nevertheless, places such as the Beer Garden and the Paradise Room were mainstays of the Māori showbands.

For Māori, the 1960s in New Zealand was full of challenges. Land confiscations, government Acts and policies saw the systematic grinding down of Māori identity and places of belonging. The Māori showband movement was essential to our history, because it was, and has been, the only time in history that a large number of musicians, performers, and entertainers have left New Zealand over a short period of time, creating as much international success as any of our top artists today.

It’s important locally to understand their impact overseas and what has been forgotten. New Zealand exported a huge amount of talent offshore during the 1960s. These performers and entertainers were highly skilled at their craft and didn’t just “pick up” their musical ability. The Māori showbands were professional, successful and extremely talented.

--

Watch: the Māori Castaways perform ‘Clementine’.

This essay first appeared in the book Okay, Boomer: New Zealand in the Swinging Sixties, edited by Ian Chapman (David Bateman, Auckland, 2020), and is published here with permission.

Louise Kewene-Doig (Tainui, Maniapoto) is a creator of music, the Suffrage 125 Community Fund podcast series Natives Be Woke, and multimedia exhibitions, and is an app developer and a scholar. She is passionate about sharing her knowledge of Māori popular music history. Louise has a Bachelor of Music and Master of Music from the University of Otago, where she is currently in the final year of her PhD studies.