Māori Hi-Five

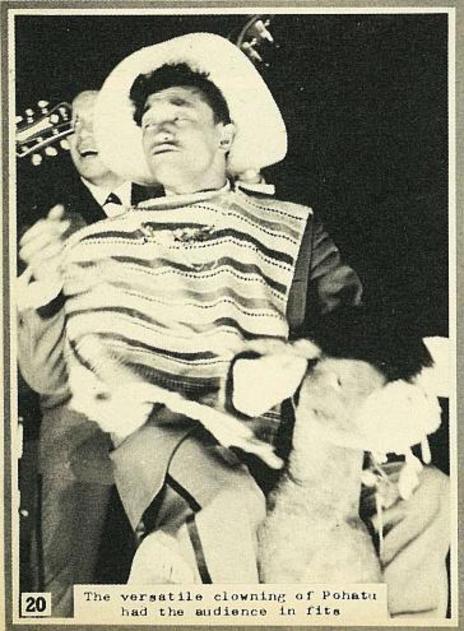

An evening with a showband was a mix of musical comedy and cabaret, tourist variety act, vaudeville show and rock and roll dance.

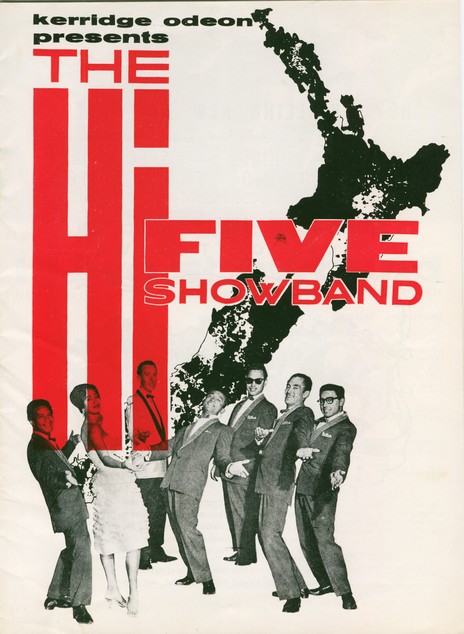

1963 tour programme

Photo credit:

Chris Bourke Collection

The 1960 double A-sided single Oasis / American Patrol on the Australian Rex label

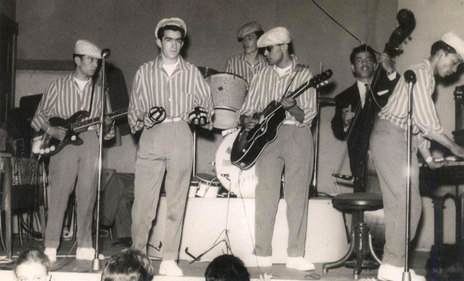

The Hi-Five Mambo in Wellington in the early 1960s

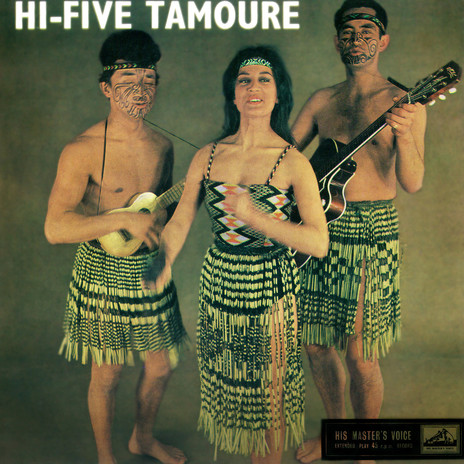

The Māori Hi-Five - Hi-Five Tamoure (1963)

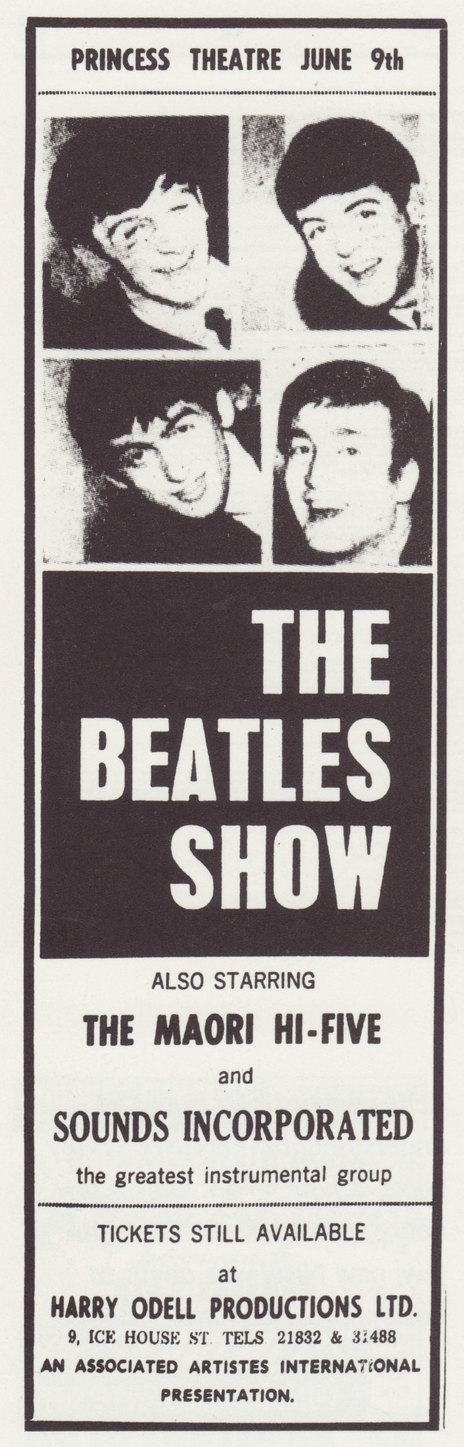

The Hi-Five support a certain band in Hong Kong in June 1964

The Hi-Five Mambo in Whanganui, October 1958: Ike Metekingi, Costa Christie, Jimmy Rivers, Rob Hemi, 'Fro The Pro' (a guest), and Sol Pōhatu.

Photo credit:

Costa Christie collection

Solly Pohatu documentary on Waka Huia, 2016

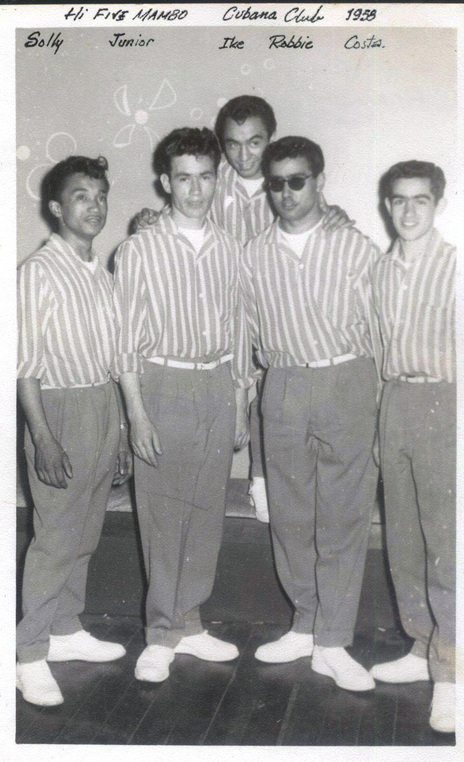

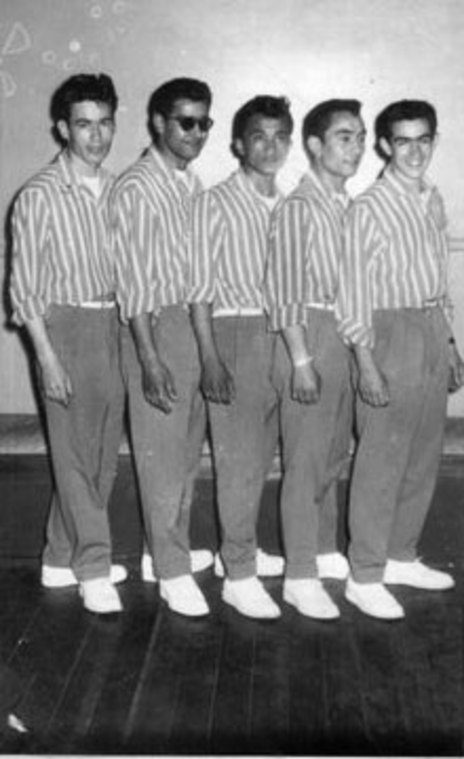

Hi-Five Mambo at The Cabana Club, Wellington, 1958: Sol Pōhatu, Jimmy "Junior" Rivers, Ike Metekingi, Robbie Hemi and Costa Christie

Photo credit:

Costa Christie collection

On the Australian Leedon label, the eponymous 1963 album by the Māori Hi-Five is considered their best

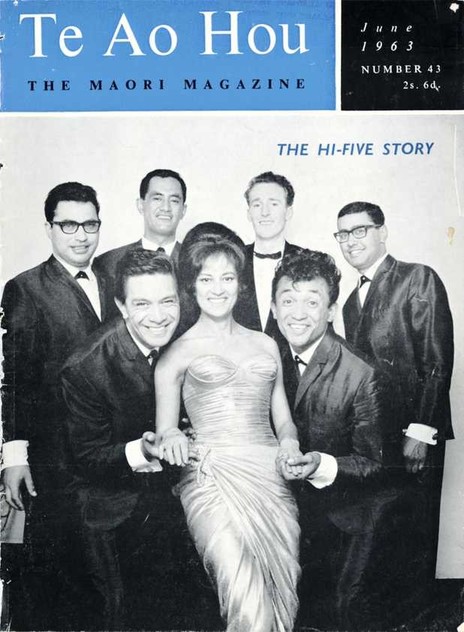

The Māori Hi-Five on the cover of Te Ao Hou, June 1963.

Photo credit:

Ans Westra

The Māori Hi-Five - Instrumental International (1960)

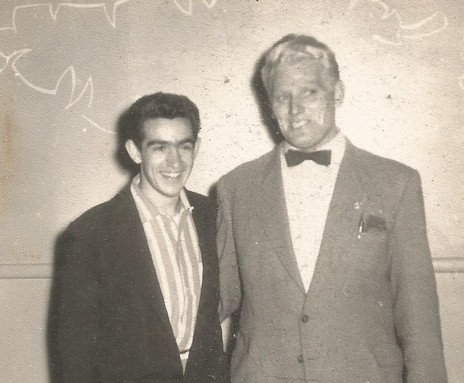

Wellington, 1958: Costa Christie, left, with original Hi-Five manager Jim Anderson. Later known as "Big Jim" in Sydney's King's Cross, he was an associate of notorious nightclub operator Abe "Mr Sin" Saffron. In 1970 Anderson fatally shot a "standover man" in a Sydney nightclub.

Photo credit:

Costa Christie collection

Leedon was an Australian label owned by American promoter Lee Gordon and Australian rocker Johnny O'Keefe. The Māori Hi-Five recorded three albums for the label, with Serenade In Blue being the first, issued in February 1961.

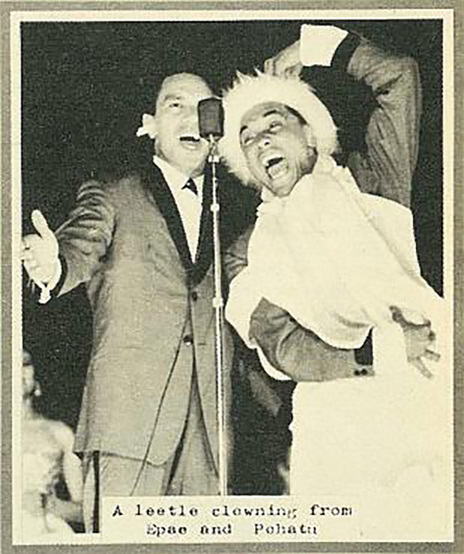

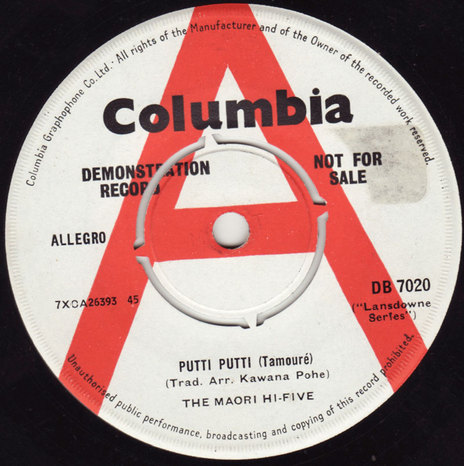

Putti Putti

The Māori Hi-Five in London with their Roller, 1962

My Blue Heaven

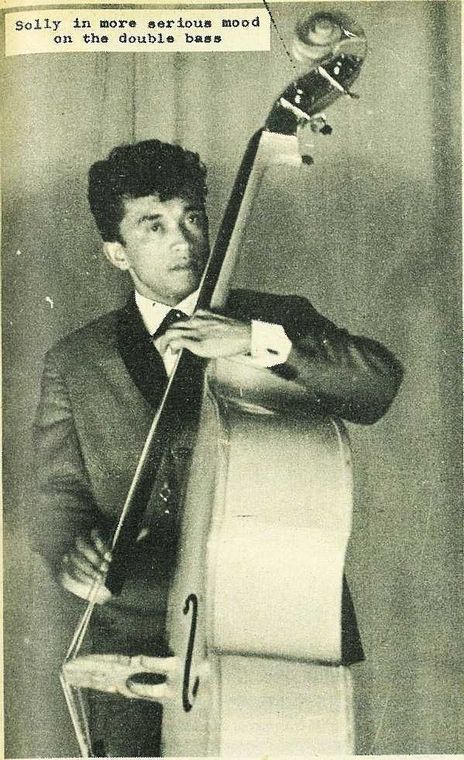

Gisborne being entertained by King Solomon Pōhatu

Photo credit:

Gisborne Photo News

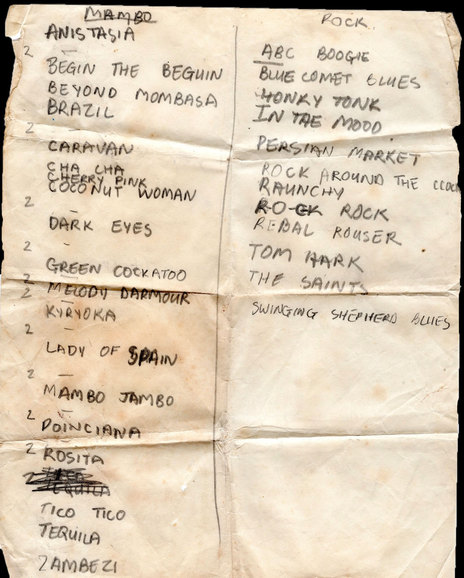

1958 (Māori) Hi-Five Mambo song list comprised mostly of Latin tunes reflecting the 1950s popularity of groups like Luis Alberto Paraná and the Trío Los Paraguayos.

Photo credit:

Costa Christie collection

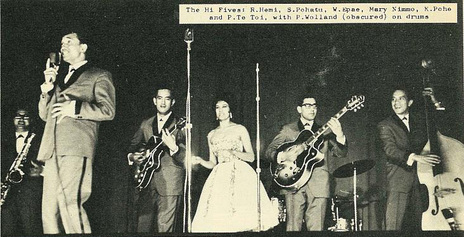

Māori Hi-Five in Gisborne, April 1963 (L-R): Wes Epae, Mary Nimmo, Kawana Pohe, Paddy Tetai, Peter Wolland, Robert Hemi, and Solly Pōhatu.

Photo credit:

Gisborne Photo News

From left: Mary Nimmo, Kawana Pohe, Paddy Te Tai, Peter Wolland, Robert (Hemi) Te Miha, Solly Pōhatu and (front) Wes Epae. This photo originally appeared as the cover of the 1963 Māori Hi-Five EP, released on Odeon in Sweden and HMV in New Zealand.

Photo credit:

Playdate, April 1966

The 1963 single Putti Putti, released in the UK on EMI's Columbia label

The Māori Hi Five in Nelson, 1963

Photo credit:

Nelson Photo News

Poi Poi

The Māori Hi-Five in June 1964 in Hong Kong with The Beatles: Paul McCartney, Wes Epae, John Lennon, Kawana Pohe, Paddy Te Tai, George Harrison, Robert Hemi Te Miha, Solly Pōhatu and the local booking agent Frankie Blair. In front is the assistant manager of the Hotel Escalante. Ringo Starr joined the tour later, after having his tonsils removed in London.

Paddy Tetai, Mary Nemmo, Wes Epae, and Solly Pōhatu

Photo credit:

Gisborne Photo News

Hi-Five Mambo, from left: Jimmy Rivers, Rob Hemi, Sol Pōhatu, Ike Metekingi, Costa Christie. Taken at the Cubana Club, Wellington 1958

Photo credit:

Costa Christie collection

Māori Hi-Five, Pigalle Club, London

Hippy Hippy Shake

Members:

Solomon Pohatu

Rob (Hemi) Te Miha

Fred Tira

Junior Tuatara

Paddy Te Tai

Costa Christie

Kawana Pohe

Tuki Whittaker

Peter Wolland

Wes Epae

Charlotte Pohe

Mere Nimmo

Labels:

Leedon

HMV

Columbia

Rex

Discography

Trivia:

In December 1961 in Disc magazine, producer George Martin is quoted as saying "I have just signed an outfit that does sound different – the Māori Hi Fives. I think they’ll be a sensation". Sadly nothing seems to have come of this.