The one thing that is beyond dispute is that Ike Metekingi formed the very first Māori showband.

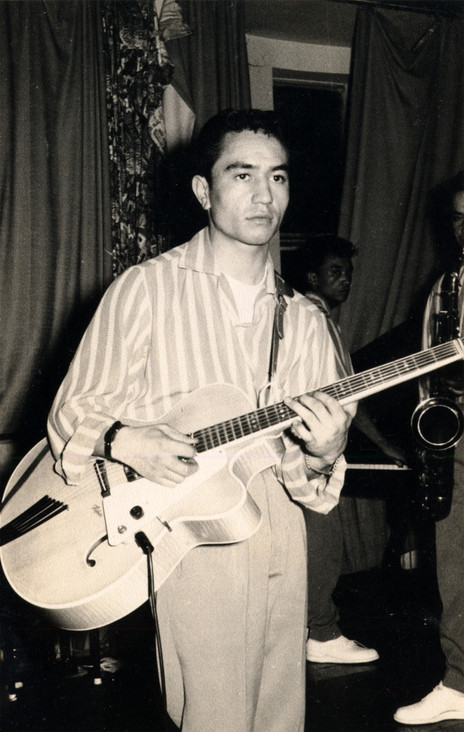

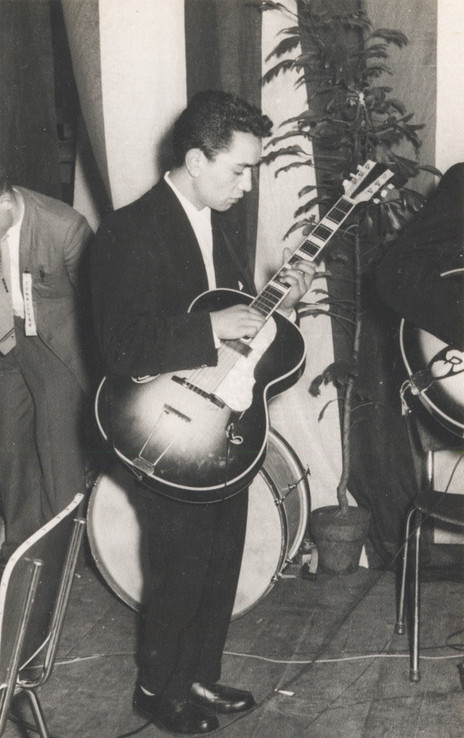

Although it was often difficult to ascertain exactly what role he had in any number of acts or events, the one thing that is beyond dispute is that Ike Metekingi formed the very first Māori showband, the Māori Hi-Five, and for that alone he deserves a special place in New Zealand music.

Ihaka Epiha Turoa Metekingi was born 19 February 1940 at Rānana, 60kms up the Whanganui River. He spent his final years in a kaumātua flat at Pūtiki Marae, near Whanganui township, and died on 1 February 2011. He married Valerie in 1959: four kids, separating in 1979. The scoundrel left Val for a younger partner, another child followed, but the relationship didn’t last.

Those are the basics and there’s little more to go on. Ike was notoriously reticent, happy to swap yarns late into the night but mention “interview” or present a recording device and he clammed up pronto. I got to know him pretty well over his last 20-plus years, but really know him? Over the years he gave me a wealth of stories, some of which I considered suspect but enjoyed the telling anyway, and I’d find out later, from another source, that the tale was indeed true.

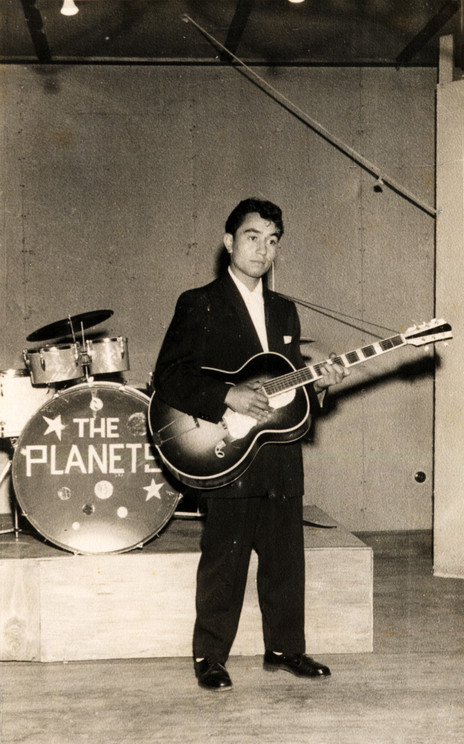

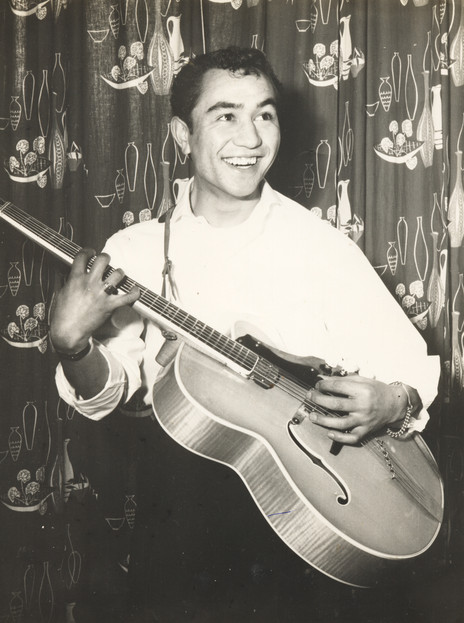

Some of his reminiscences I remember clearly. Young Ike, pre-teens, sitting outside at the window listening to his elders singing and playing; teaching himself the ukulele, progressing to the guitar; forming his first band, The Planets, at age 15 with Kawana Pohe, performing at local marae; backing Johnny Devlin; talent quests at the Whanganui Opera House. And gigs further afield: Auckland, Wellington, Whakatāne, Rotorua … New York.

New York? This was a new one on me, care of Hugh Lynn: “He told me that he went to New York when he was 16, even played with a band. I can’t remember the details, he wasn’t there long, but he definitely told me that he was in New York at 16 and I’ve never had any reason to disbelieve him.”

In 1957 a tour of the lower North Island with Johnny Devlin finished at the Wellington Town Hall. Metekingi remained in the capital, the Planets were in disarray after Kawana Pohe was diagnosed with impending blindness. Frequenting the Ngāti Poneke Community Centre, Ike met Valerie, his future wife, and came up with the idea for a new band. Although not entirely ignoring the rock and roll coming into vogue, the group would perform in a variety of styles but specialise in Brazilian music.

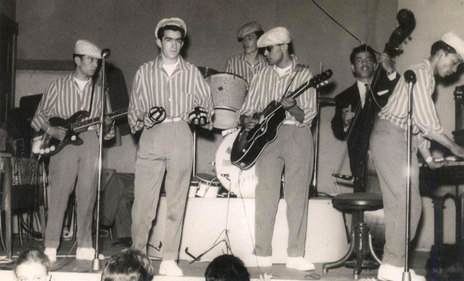

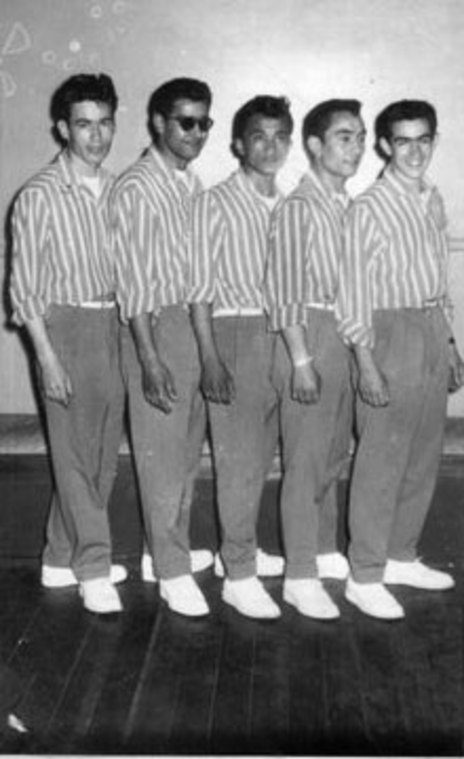

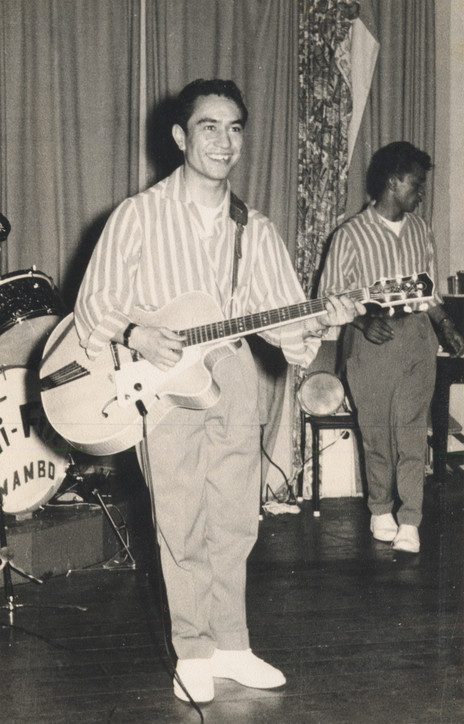

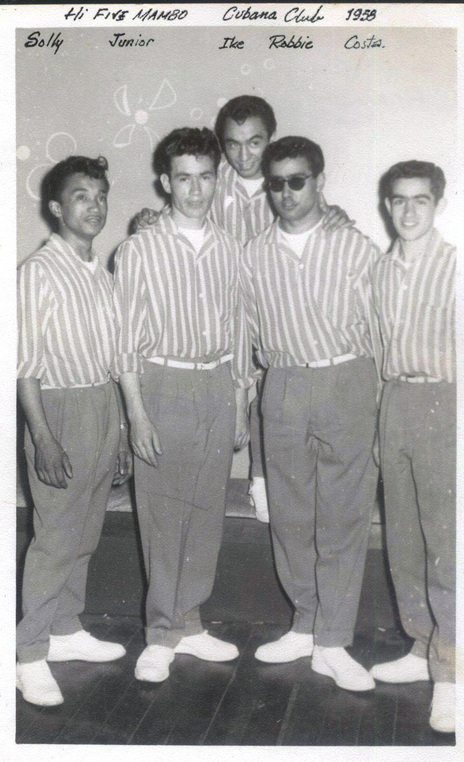

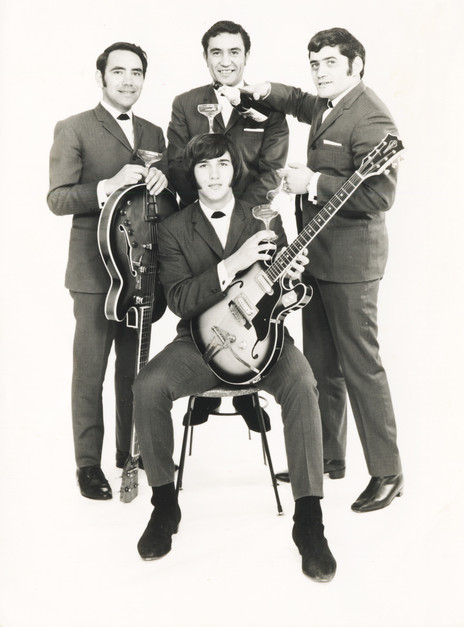

The band members were culled from around the country, Wairarapa to Ruatoki, and included Kawana Pohe, sprung from the Auckland Blind Institute. Billed as The Hi-Five Mambo, they started playing around Wellington at the beginning of 1958, making an immediate impression, not least on two recent immigrants, Scotsman Jim Anderson and Englishman Charles Mather. Anderson and his wife managed a Cuba Street coffee bar, the Cubana, which is where the new group cut its teeth. Managed and mentored by Mather and Anderson, they renamed themselves the Maori Hi-Five and, later, the Maori Hi-Five Showband. The Māori showband era had begun.

Ike was always adamant that he had no knowledge of the Irish showbands, a post-World War II phenomenon which had remarkable similarities to the Māori variety: an eclectic repertoire that included traditional Celtic music, and popular songs, dancing and comedy. But surely Anderson and Mather would have been aware of the Irish showbands’ existence?

Regardless, the Maori Hi-Five soon outgrew the Cubana and in 1959 Anderson and Mather leased the Trade Union Building in Vivian Street as their headquarters. As it turned out, Metekingi didn’t remain long in the band he had formed, remaining in Wellington when Anderson took the Hi-Five to Sydney in January 1960 to immediate success. Inspired by this, Metekingi and Mather started mentoring similar showbands, such as The Hi-Quins, The Quin Tikis, The Fireflies (featuring a young Malcolm Hayman), and the Premiers.

Val Metekingi has few fond memories of the time: “Charles Mather was alright but Jim Anderson was just awful. The real reason why Ike didn’t go to Australia was because Anderson didn’t want married members in the band. When Solly Pohatu’s girlfriend fell pregnant, [Anderson] barred her from the Cubana. A horrible, horrible man. He called a meeting when he heard we were getting married, tried to make me feel guilty, saying it would be my fault if the plans fell through, that sort of thing, but Ike and I had already decided and that’s when he was replaced by Paddy Te Tai. When we got married, no one in the band was allowed to come.”

Val had other concerns. “They had these grand ideas to tour overseas in a £16,000 yacht they were going to buy so the band members were only paid 30 shillings a week, most of which went on their board: they all lived at the Victoria Boarding House in Willis Street. The band all thought it was wonderful, they were going to sail around the world and play in ports, but the yacht never happened and no one ever saw any money in its place.”

Mentoring bands to send around the world sounded grand but there was little financial return.

Money was almost always a concern for Ike and family. Mentoring bands to send around the world sounded grand but there was little financial return. In 1961, Anderson stepped back from his role as the Hi-Five manager, beginning his criminal career as the right-hand man of nightclub owner Abe Saffron (“The King Of The Cross”). Mather replaced him in Australia, and took the band to Britain and further afield. In Wellington, Ike formed his own band, The Diplomats, featuring Tuki Witika, Frank Tyson, Bill Pungihau and Massey Williams. The Diplomats enjoyed a two-year residency at the Nubanca (an anagram of Cubana, a nod to the Hi-Five’s beginnings).

In 1963 Williams developed a brain tumour, signalling The Diplomats’ demise. Ike gave music away for a while, working for Caxton Press and a stint selling New Zealand encyclopedias. The mid-1960s saw him take his growing whānau back home to Whanganui, where in 1968 he formed The Kon Tikis, resident at the Rutland Hotel before Auckland called. Keeping the band name but with a new line-up (Ronnie Devonport, Toko Pompey and John Rangi), The Kon Tikis’ popularity at the Coburg Hotel on Queen Street gained them a residency at a more prestigious Queen Street hotel, the Great Northern. Here they shared the residency with the Māori Volcanics, featuring Billy Taitoko, aka Billy T James. Ike and Billy became firm friends.

In the 1970s Ike and Val started a business directory, Pink Pages, employing Billy T, a trained commercial artist. There was less music, although Ike did form and manage The Big Dagg Band for a Fred Dagg tour. By decade’s end, with Billy T on his way to superstardom, Ike terminated his marriage of 20 years and took up with Gina; a child followed. Ike and Gina remained together for eight years, which included a return to Whanganui. “He left me for a girl,” Val says with a sigh, “she was just two years older than our eldest boy.”

In 1985 Ike returned to Auckland and, with Billy T, started The Dream Factory in Fanshawe Street, just metres away from the former Māori Community Centre, a familiar building to both. Largely financed by Billy T – although there was supporting finance from various funding bodies – the kaupapa behind The Dream Factory was a return to the mentoring approach pioneered by Metekingi and Charles Mather a quarter-century earlier. It served as a rehearsal room for Hawaiki, Billy T’s touring band, as well as a music school. Other mentors included Tuhi Timoti and Reggie Ruka, and students who passed through included Cadzo Cosser, Alex Griffith, Mark Heke, Taisha Tari and Leon Wharekura.

Griffith remembers the first time he met Ike. “Ike started by saying something like ‘no long-haired musician is going to come in here and … yadeyadeyada’. Great start, I thought, being the only long-hair in the room. I initially felt quite disrespected by Ike although, of course, a few years later I was proud to have earned his respect.”

Billy T used The Dream Factory as his escape – he even had a bed there – and when Gina fled, Ike set up house in The Dream Factory. Billy was managed by Elaine Hegan of Hegan Entertainments, and Elaine’s son Kim set up office in the building. Later, much was made of Ike Metekingi’s motives and his influence over Billy T James but Kim Hegan doesn’t buy into any of it.

“Ike played a big part in Billy T’s career,” Hegan says, “providing security and his on-call driver and during shows he was the follow spot operator. These days maybe you’d call him a personal assistant, always out front of and for Billy T, a born ‘wing man’, absolutely devoted to Billy. He idolised Billy and would often clear the way, checking the arrangements.

“Short in stature but broad shoulders, Ike was always immaculately turned out – aviator sunglasses, cowboy boots, bomber jacket. The Doy! He was Billy’s batman, anything Billy wanted, Ike would score it, literally anything. Gum chewing, foot tapping, hyped up, Ike always had a cheerful chatter, ‘chur doy’ his theme phrase.”

Hegan recalls a Billy T performance at the Ponsonby Rugby Club. “Ike had set up the follow spot on a pile of tables at the back of the room. The place was over-packed and as punters started to heave, the floor started to rumble and Ike’s platform started to move. Billy moved his body position to line up with the spot. The more the crowd laughed the more the follow-spot slipped until Billy was lying on the floor and then the whole follow-spot tower toppled with Ike hanging on for dear life all the way to the floor. I will always remember little Ike looking up, spread-eagled on the floor, squashed underneath this massive light. ‘I’ve got it, doy, all good, doy’. Priceless!”

The Dream Factory was never going to survive, despite the best intentions, and when it was closed in the late-1980s, the now-homeless Ike shifted into Whare Tapare, the Kingsland “entertainment school”, which served as Herbs’ headquarters. Ike held court there for two years, Tim Shadbolt moved in briefly; Billy T, naturally, was a regular visitor. Billy’s death in 1991 affected Ike immensely and shortly afterwards he returned to Whanganui, ostensibly to become a tohunga. He’d been summoned to study traditional skills up the Whanganui River for many years but he’d left it too late. “You’re too old,” he was told. He stuck around anyway, picking up more knowledge before returning to Auckland in the late-1990s, renting a shop on Karangahape Road, which served as home and workplace, making leather items, belts, guitar straps and cigarette lighter holders, and whips and corsets for the working girls.

In 2001, visiting Hugh Lynn at his large Mt Eden home and former dance studio, he accepted a bed for the night. He was still there four years later. “He’d spend all day doing his leather thing,” Lynn remembers, “and it always amazed me at the length of time for such a small return, ten or twenty bucks. Maybe it was a meditation-type exercise. He had no other income and it took me a couple of years to convince him to go on the dole.”

Ike was full of surprises; just when you thought you had a handle on the man, he’d spring something else. Sitting around Hugh’s office one evening, my ex, Dot, mentioned that her father came from a small Scottish town named Buckie. “I’ve been to Buckie,” said Ike, “halfway between Aberdeen and Inverness. Seaside town, bloody cold place.” When I expressed my amazement, Ike refused to elaborate, just saying mysteriously, “There’s a lot about me you don’t know.”

He once told me that he flew to Sydney to sort some problems for one of the showbands, which was stranded on one of the Pacific Islands, with passports confiscated, and equipment and belongings in bondage. Ike turned to Jim Anderson, the former Hi-Five manager, who directed him to wait at the El Alamein Fountain. Anderson turned up with a satchel of cash, telling Ike, “This is straight from Abe Saffron so make sure it’s paid back.”

And then there was Ike’s claim that in 1969 he declined the offer of the New Zealand franchise for a takeaway chicken business: “I didn’t think it would work.” The franchise was Kentucky Fried Chicken.

In 2005 Ike moved back to Whanganui one last time, settling into that kaumātua flat. I moved to nearby South Taranaki shortly after and called in to see my old mate every three to four months. He was always … Ike: always cheerful, despite ailing health, always entertaining, always hospitable in his tikanga way, always greeting you with that familiar ‘Chur, doy!’

In 2009, shortly following the publication of the Billy T James biography, I called in to see him, outraged at the book’s flaws, not least being its portrayal of Ike. Ike was unperturbed.

The subsequent telemovie based on the book was worse, although it was hard not to laugh at Ike as a six-foot thug. And Ike with a gun! He may have shot himself in the foot a few times but Ike Metekingi and firearms? “Fucking ludicrous, pure fantasy!” says Ruby James.

The last time I called into Pūtiki Marae, Ike, by now clearly unwell, showed me an invitation to a forthcoming reunion of Māori showbands at Auckland’s Bruce Mason Centre. The accompanying letter detailed return travel plans from Whanganui to Auckland, five-star accommodation, all the trimmings. A hospital appointment clashed and Ike Metekingi, the event’s VIP guest, didn’t attend. He died four months later.

During that last kōrero with Ike, I asked him what he was most proud of, career-wise. “Well it took me a long time of study but I am now a Master of Nothing. I think about nothing and I do nothing.”

Chur chur, doy. Ike Metekingi, Master of Nothing, eccentric to the end. Hei maumaharatanga ki te tino hoa ...