In April 1963 Wellington radio station 2ZB launched a new programme that played the latest pop records every week night. For a generation of young listeners, myself included, The Sunset Show was the gateway drug to a lifetime of listening.

It’s hard to imagine what a scarce commodity pop music was in New Zealand at that time. Virtually all radio, including commercial stations such as 2ZB, came under the authority of the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation. Catering to the broadest of audiences, programming inevitably skewed towards the conservative.

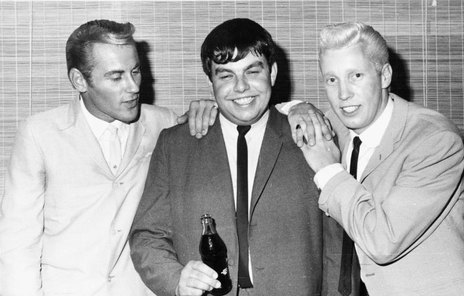

Justin du Fresne at 2ZB in the 1960s. - du Fresne family

To tune in to any of the NZBC stations you would hardly be aware of the kind of music teenagers around the world were living their lives by. For years the closest thing was the Lever Hit Parade, sponsored by soap manufacturer Lever Bros., which once a week played the eight records deemed to be the country’s current favourites, though the selections were not based on actual sales and would include movie themes and crooners as well as rock’n’roll. Or you might catch Neville “Cham the Man” Chamberlain and Des Britten, young disc jockeys who had honed an upbeat American-influenced patter on Hawke’s Bay’s 2ZC and were now at 2ZB fronting syndicated shows “with the modern sound” and “the latest and the greatest”. But Britten’s Hi-Fi Club Show and HMV Platter Spree and Chamberlain’s Gather Round were confined to weekly half-hour slots.

But with a shortwave radio it was possible to pick up the powerful signal from Sydney station 2UE which had been basing its round-the-clock format of modern pop on the Top 40 of US radio since the late 1950s. Johnny Douglas, a producer at 2ZB, was aware of the radio revolution taking place across the Tasman. After visiting Sydney, back at NZBC Head Office he pitched the idea of a nightly programme centred on the tastes of teenagers. He had his eye on the early evening slot, the period between 4.30pm and 7pm now known as “drive-time”, when workers are heading home or preparing dinner, and young listeners are home from school and seeking distractions from their homework.

A glance at a typical mid-week schedule from early 1963 shows what a musical dead zone this time slot was:

4.30pm Vera Lynn

4.45 Current Tunes

5.00 Orchestral Parade

5.30 Country Dance Music

5.45 Kiddies Corner

6.00 Strange Tales From Hawaii

6.04 Music For Dining

As Douglas described it to Chris Bourke in 2008: “There were a series of little quarter hour blocks of no consequence, some programme guy who had to make out the headings for the week just dreamt them up off the top of his head and put them in the Listener and we – those of us who came along to actually make the programmes – would look at each other and say ‘Oh my God, accordion favourites again, what are we going to play here?’ So that was the sort of programming and I just thought we had to get rid of that.”

Broadcasting House, 1966. - Oswald Ziegler

It was Douglas’s contention that if a song was popular it should be played often, something else that went against the prevailing wisdom at the time. He recalled: “When I first went to [work at] 2ZB the manager said to me ‘There’s one thing I must tell you Mr Douglas, and that’s that we only play hit records once a week.’ And of course that’s not the way hit music works! So people had this incredible thirst and craving for music they couldn’t hear”.

Douglas had recently produced a Sunday afternoon half-hour featuring new releases, Sounds Of 62, presented by Justin du Fresne, a young broadcaster and musician who, like Britten and Chamberlain, came from Hawke’s Bay. Together Douglas and du Fresne conceived The Sunset Show and put their proposal to station manager Jim Hartstonge, who agreed to a nightly 90 minute programme, with Douglas’s reassurance that their selections would not be indiscriminate and would be “nice palatable music”.

“There was a huge amount of trust being placed on us,” Du Fresne recalled.

“There was a huge amount of trust being placed on us,” du Fresne recalled in 2007. “One false move and you’re in trouble. We were told, you know, Jim was putting his career on the line.”

The programme kicked off on 29 April 1963. The first song played was Cliff Richard’s ‘Summer Holiday’, which was unlikely to upset too many of the station’s regular listeners. Cliff had emerged five years earlier as Britain’s answer to Elvis, but had quickly toned down his act and was on his way to becoming a celibate evangelical Christian. But his popularity was about to be eclipsed by that of a certain beat group from Liverpool.

The release of the first Beatles records in New Zealand coincided almost exactly with the launch of The Sunset Show and in many ways set the programme’s tone and tempo. Whether or not their music conformed to Douglas’s “nice and palatable” promise was a moot point; The Beatles’ appeal was irrepressible.

A personal testimony: as a five-year-old in 1963 I was introduced to Beatles records by my teenage cousins. They had me hooked at ‘Twist and Shout’. Though my parents were dedicated 2YA listeners for the world news and local weather, I discovered that if I snuck the dial to 2ZB around dinner time I could usually hear a song by The Beatles.

On the back of the Beatles came a phalanx of British guitar and harmony bands – The Hollies, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Herman’s Hermits, The Searchers, The Dave Clark Five – often with a softer edge than their Liverpool counterparts. The Searchers, with their “tight harmonies and smart suits” were a particular favourite of du Fresne’s. Others, it turns out, never made it to the show.

Douglas: “There were records I must admit that I used my own discretion on, if they were too noisy and too screamy like ‘Do You Love Me’ by Brian Poole and the Tremeloes. I just felt it was a bit over the top. A lot of people said to me, Oh you’re just a ridiculous conservative old fool, but in actual fact at that particular time and that particular place it was just not appropriate.”

The show continued to moderate its playlist by offsetting the electrified Beatles with smooth balladry from the likes of Andy Williams, country songs (Douglas observed that “New Zealanders had a real underlying liking for country music” which tied with his own fondness for Jim Reeves) and the “trad” jazz of British revivalists such as Acker Bilk and Kenny Ball. The clarinet-playing Bilk had been the last big thing in Britain before The Beatles, his dreamy instrumental ‘Stranger On The Shore’ being that country’s biggest selling single of 1962.

As for Kenny Ball, du Fresne’s enthusiasm earned him an official reprimand from head office for “a serious breach of advertising policy” when his noting of an upcoming concert tour by the trumpeter was construed as effectively being a free commercial. “This breach is regarded as serious,” an official memo informed du Fresne, “and the relevant papers covering the matter have been placed on your personal file in Head Office.”

By the end of 1963 du Fresne had left The Sunset Show – temporarily as it turned out – though not because of any on-air indiscretions. He was off to Europe to try his luck with his own pop-folk trio, Harbour Lights.

Peter Sinclair and Sunset Show producer Johnny Douglas broadcast from the Galaxie, Auckland, with The Gremlins. Clockwise from top left: Roger Wiles, Johnny Douglas, Ben Grubb, Peter Davies, Paddy McAneney, Glyn Tucker, Peter Sinclair, and Alex Behrens of Terry and the Nitebeats.

From early 1964 The Sunset Show had a new host. Pete Sinclair was born in Australia but grew up in Christchurch, where he attended Christ’s College and had a brief stint at the University of Canterbury studying English, Philosophy, Psychology and Greek, though he never completed a degree. A natural performer, it was his involvement in a university revue that led him into broadcasting. While encamped in Hagley Park as part of a stunt to promote the revue, he was interviewed by a Radio New Zealand reporter who suggested he had the right sort of voice for radio. With no other career plan, he took the reporter’s advice and was soon fronting programmes on the local 3YA and 3YC stations. After a stint in Greymouth – where he is remembered for wearing a purple suit, with purple shoes – and a brief spell in Sydney, he got the call to the capital.

Sinclair’s ebullient presence took the programme’s popularity to the next level

His ebullient presence (“Hi there! It’s Pete Sinclair!”) took the programme’s popularity to the next level. On-air competitions drew teenage listeners to the newly opened Broadcasting House in Bowen Street, where they would party in the reception area outside the studio. Through the soundproof window they could watch Pete spinning the discs and rattling off a between-song patter that sometimes challenged their vocabulary. Teenage listener and later radio producer Simon Morris remembers Sinclair introducing a track by British R&B band The Pretty Things and “referring to their name as being ‘antonymous’ [having an opposite meaning], which amounted to a fairly advanced language lesson for a teenage pop show.”

In addition to his gift of the gab, Sinclair’s sharp suits and perfect hair made him an instant icon. When the NZBC launched its first pop television show Let’s Go in mid-1964 with Sinclair as compère, his fame went nationwide. At an outside broadcast in Porirua he was mobbed by fans. When The Beatles arrived in Wellington in July 1964, he was escorted through the throngs outside the St George Hotel to meet them.

On a personal note, my family lived at the time in Sydney Street West, just 400 metres from Broadcasting House. At age six, having learnt that building was the source of the music I was fast becoming addicted to, I decided one evening to pay a visit to The Sunset Show. I persuaded my sister, age four, and brother, two, to accompany me on the adventure. We were out the door and down the road before Mum, who was in the kitchen cooking dinner, realised we were gone. When Dad arrived home he found her calling our names up and down the street. Neighbours were summoned to help in the search. Someone called the police. A woman up the road was listening to The Sunset Show when she heard the shouting and leaned out the window. “If you’re looking for your kids you better turn on your radio,” she told my astonished parents. “They’re on the air right now.”

Pete Sinclair (left) and Lew Pryme flank Wellington promoter Ken Cooper, c. 1965. - Ken Cooper Collection

With Sinclair’s skills now stretched across both radio and television, other presenters such as Relda Familton were sometimes called to cover for The Sunset Show, and by 1965 Justin du Fresne was back in the hot seat. It was during this time that Gordon Campbell, then a young broadcasting employee, worked on the show. “I had no input into the music selections, that was purely Douglas and Justin,” he remembers. “My role was limited to providing Justin with things to say before and after he played the record. So I’d see a playlist and type out stuff: who these people were, who the songwriters were, what else they wrote/produced/ sang on, etc. Example: The Righteous Brothers’ revival of ‘You Can Have Her’. This was written by Bill Cook, formerly the road manager for Roy Hamilton, who had the original hit version.”

Campbell, who a decade later would pioneer serious rock writing in New Zealand with an influential column in the Listener, recalls his disdain for the corporation policy that guided the playlist. “There was an expectation that the show would play bright poppy tuneful music, and nothing too raucous or challenging in style or content. No sex, no drugs, no politics. It was an era when drugs were suspected to be lurking behind many obscure pop lyrics but the NZBC largely took its lead from the BBC when it came to ‘banning’, i.e. not buying or playing certain tracks on The Sunset Show.

“One day I’d had enough and came out of my corner and picked one of Douglas’s favourites – ‘Bus Stop’ by the Hollies – and made an argument that it was too noisy for the show. You know, too raucous. Too much treble on the voice. Unfortunately, he didn’t realise that I was mocking him. It just confirmed his view that I was unhelpfully weird.”

Gordon Campbell savours one victory: getting Bob Dylan played on the show

Campbell does, though, savour one victory: getting Bob Dylan played on the show, previously problematic on account of his unvarnished voice and political and possibly drug-inspired lyric content. “I played Justin ‘She Belongs To Me’ which was the flip of the ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ single, and that became his gateway to liking Dylan.”

Though Dylan covers recorded by the likes of The Byrds, Turtles, and Manfred Mann would still feature more frequently than the man himself, Dylan would subsequently be heard from time to time. Decades later, poet Jeffrey Paparoa Holman would dedicate a collection to “Pete Sinclair, the 2ZB Sunset Show host who played ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ on air for me in 1965”.

The show also played a part in launching local artists. With hits such as ‘Don’t You Know Yockomo?’ and ‘Do the Bluebeat’, Dinah Lee’s bubbling blend of Jamaican ska and New Orleans rock’n’roll was a perfect fit, as were the guitars-and-harmonies of local beat groups including The Librettos, The Pleasers, Ray Columbus and the Invaders and Max Merritt and the Meteors.

Other stations around the country soon launched their own variations on The Sunset Show. 1ZB in Auckland had the Twilight Special. 3ZB in Christchurch had The Sound Show. 4ZB in Dunedin had The Big Beat. 2ZA in Palmerston North had The Twilight Show.

Yet ultimately young people’s desire to hear what they regarded as their own music went beyond what The Sunset Show and its imitators had to offer. While John Douglas would boast that The Sunset Show had made a national No.1 of Jim Reeves’ ‘I Love You Because’ (which had only reached No.54 on the US chart), there were some listeners who didn’t appreciate having their jangling guitars and high-powered harmonisers interrupted by the urbane crooning of Gentleman Jim and his ilk.

The Sunset Show happily embraced the gentle tones of The Supremes and Mary Wells, but harder-edged Motown records by The Four Tops or Marvin Gaye saw little if any airplay during these years, while the even tougher R&B sounds coming from the Atlantic and Stax labels – Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave – would sometimes not even be purchased by the NZBC.

After briefly hosting The Sunset Show, Rick Grant moved to the original pirate station, Radio Hauraki. - Adrian Blackburn Collection

Meanwhile the Beatles were showing how to use the long-playing album as a creative canvas with albums like Rubber Soul and Revolver, and a higher wattage rock was being pioneered by bands like The Who, Cream and Jimi Hendrix Experience. Neither album tracks nor the more experimental singles of bands like these were part of the Sunset Show’s purview.

Responding to need, in late 1966 the pirate station Radio Hauraki was launched, broadcasting to the Auckland region. As Murray Cammick put it, “Radio Hauraki did not need to worry about the meaning of ‘Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds’ or what the Small Faces were doing in Itchycoo Park.”

In late 1966, NZBC launched C’mon, a new weekly television pop show, directed, as Let’s Go had been, by Kevan Moore, and fronted once again by Pete Sinclair. With Sinclair’s increasing television commitments, expatriate Australian DJ Rick Grant took over briefly before becoming one of the “Good Guys” at Radio Hauraki. (Grant was tragically lost at sea, the night of Hauraki’s last shipboard broadcast in 1970.)

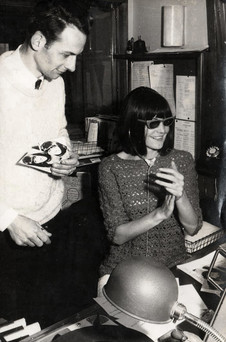

Keith Richardson with touring UK pop star Sandy Shaw, 1965. - Keith Richardson Collection

Keith Richardson – who, like Des Britten and Neville Chamberlain hailed from Hawke’s Bay – took over the The Sunset Show in September 1967. Richardson showed enthusiasm for local pop acts such as The Avengers, The Fourmyula, The Simple Image, The Dizzy Limits. The Avengers were a particular favourite. He previewed their latest singles and they recorded personalised jingles for his show. They even backed him on a single of his own, ‘Lovin’ Sound’ (released in April 1968), though it failed to chart.

But the gulf between The Sunset Show and a maturing audience continued to widen. For those with more esoteric tastes, 2YD had Big Beat Ball, where veteran broadcaster Arthur Pearce, under the alias Cotton-Eyed Joe, would play mostly imported US R&B by artists you wouldn’t hear – or even hear of – anywhere else, from James Brown to The Fabulous Counts. A blues cult spurred by the influence of British bluesmen like John Mayall and Eric Clapton spawned Midge Marsden’s Blues Is News programme on the recently launched 2ZM. The station would also present evening features on artists as uncompromising as Sly and the Family Stone and The Incredible String Band.

The Sunset Show saw out the 60s, but by 1970 the sun had truly set. When seasoned Christchurch announcer Murray Forgie took over the slot that year it was with a name change. It became The Murray Forgie Show.