On the late Andy Shackleton’s Memories of New Zealand Musicians website, members of the Dizzy Limits share vivid recollections of those inauspicious beginnings. Stu Johnstone remembers the 12- and 13-year old Pickadors eagerly becoming members of Mirimar’s St Aidans Anglican Church so they could perform at youth club dances – and meet girls:

“The next Sunday morning four 12- and 13-year-old heathens perched themselves in pews eyeing up the young females present, after which we lugged our drum kit and tiny amps into the adjoining hall and started belting out such classics as ‘If I Had a Hammer’, ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’, ‘Apache’, ‘Bad To Me’ and ‘The Highland Fling’. Even though our amps ranged in size from only 5 watts to 20 watts, our performance that day ended with one of the few old people there telling us mid-song that we were too loud then immediately disconnecting our amps from the power supply.”

“the bass drum left the stage and crashed into the supper table knocking cakes onto the floor”

Steve McDonald recalls his first gig with the Strangers at the Railway Shunters Ball: “A very prestigious name for a not-so-prestigious event. We dressed up in Beatles shirts and jackets along with (plastic) Beatles wigs! (Can you imagine?) We came running on to the stage and as I reached my drum kit I slipped and went headfirst into the drums. They rolled everywhere taking out microphone stands, and the bass drum left the stage and crashed into the supper table knocking sandwiches and cakes onto the floor. We in the band thought it was hilarious but the faces on the patrons were faces of shock and dismay. Strangely enough we were never asked back to the Railway Shunters Ball.”

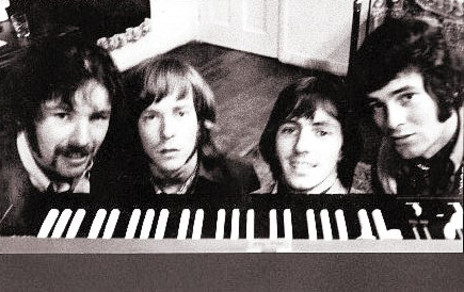

The only way was up. As The Dizzy Limits, the newly formed quartet – all still third and fourth formers – developed a repertoire that favoured the fashionable Britpop of the day: Beatles, Rolling Stones, Small Faces, Kinks, Animals. Over the next few years they progressed from youth club and school dances to regular gigs in Wellington nightclubs such as The Place and Ali Baba’s, as well as the Sunday afternoon dances in the Lower Hutt Horticultural Hall.

For their Wellington gigs, they had access to a van, albeit with limitations. Frits recalled to Andy Shackleton that “Steve’s dad allowed us to use his company van, a small Morris Minor. Our gear expanded and one particular Saturday afternoon while loading, the van overflowed and we couldn’t fit everything in. The solution was to cut the PA speakers in half, then drill holes in one end and glue doweling in the other – very creative! These puny columns had five 8-inch Pye speakers in each. They served us well for a few years. Hard to imagine now!”

The band also ventured outside Wellington’s environs, often playing in Rotorua, Napier, Palmerston North, Wairarapa, and occasionally Nelson, Christchurch, and Dunedin. They frequently shared stages with other prominent bands from the Wellington area such as The Fourmyula, Tom Thumb, Bari and the Breakaways and The Avengers, as well as backing touring stars including Allison Durbin, The Chicks, Shane, and Larry Morris.

As keyboards became an increasing feature in 60s pop, Stu Johnstone – a trained classical pianist – shifted from bass to keyboards, while Frits took over the bass. Another feature of the sound they worked on was their harmony vocals. All four members sang, lending lustre and depth to such popular songs as the Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’ and the Tremeloes’ ‘Silence Is Golden’.

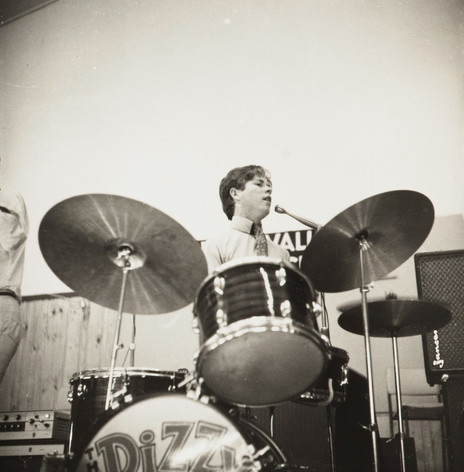

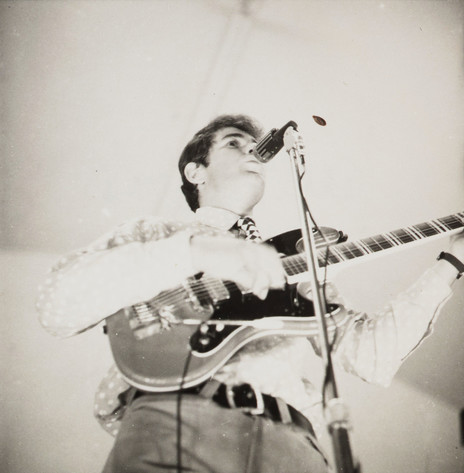

In his book When Rock Got Rolling: The Wellington Scene 1958-1970, Roger Watkins notes that a distinctive feature of the Dizzy Limits at this time was that Steve, like The Human Instinct’s Maurice Greer, played his drums standing up.

By 1968 they had dropped the plural from their name, becoming simply Dizzy Limit.

At the start of that year they took up residency at the Caltex Lounge on lower Taranaki Street, Wellington. In April they won the Wellington regional final of the Battle of the Bands, though they lost the grand final to Auckland’s Dallas Four, who disbanded without ever taking up their prize.

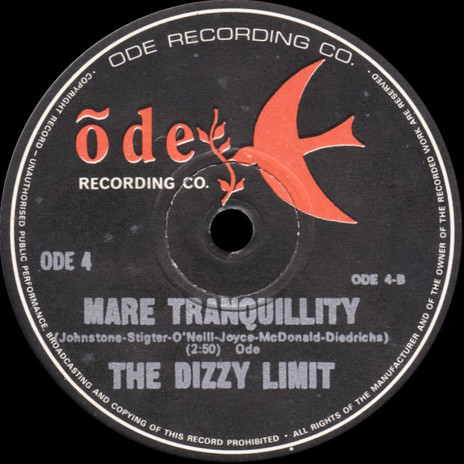

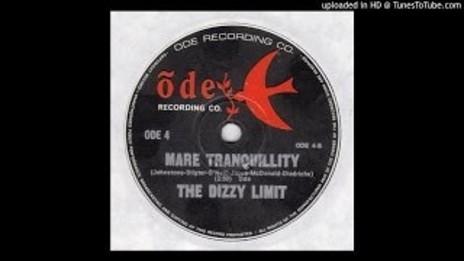

‘Mare Tranquility’ took full advantage of the psychedelic “phasing” effect then in vogue

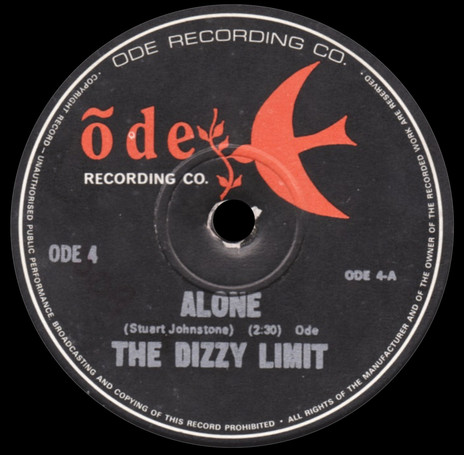

The next year they signed to Ode Records, the Wellington independent label run by Terence O’Neill-Joyce. Cashing in on the fever around the first manned Moon landing, which took place that July, their debut single would be titled ‘Mare Tranquility’ after the lunar sea where the Apollo 11 crew touched down. Recorded at HMV studios and taking full advantage of the psychedelic “phasing” effect that engineer Frank Douglas had figured out by studying current records from overseas, the composition was credited to all four members of the band, plus O’Neill-Joyce. It was essentially an instrumental, though it culminated in a vocalised chorus of “Mare Tranquility”, repeated until eventually the voices were completely engulfed in phasing. The record was not a hit, although it received some airplay in the Wellington region.

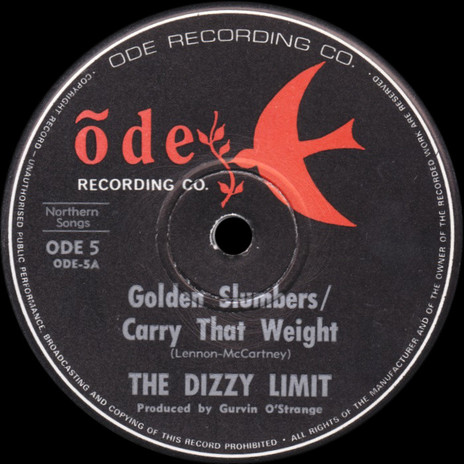

A follow-up single fared slightly better. O’Neill-Joyce had an advance copy of The Beatles’ new Abbey Road album and encouraged the Dizzy Limit to record a faithful cover of the ‘Golden Slumbers / Carry That Weight’ medley, which was released as a single, reaching No.7 in the New Zealand singles chart (as voted by Listener readers) in December 1969.

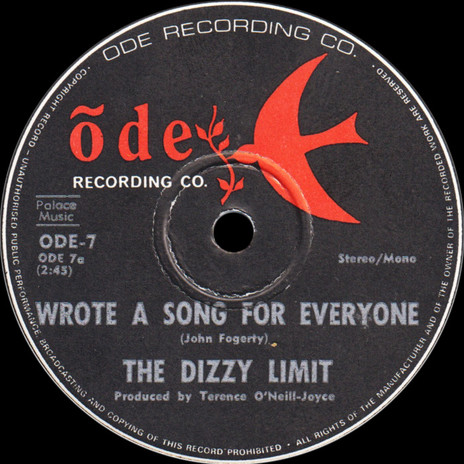

At the end of 1969, Kelvin left the group, to be replaced by John Donoghue who had previously played with Steve in the Strangers and had more recently been a member of The Cheshire Katt. The new lineup was showcased on the next single, released in early 1970: a cover of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s ‘Wrote A Song For Everyone’. This time a television clip was shot: a Beatle-esque romp that, as John Donoghue recalled, “included the band chasing a train out of Wellington Station, clowning around on a playground at Kilbirnie, clambering over a monument on Mount Victoria, and ended with us stealing a couple of dinghies at Evans Bay.”

Though the television clip should have guaranteed the group national exposure, it was withdrawn after a single screening following a complaint about the group being shown clambering disrespectfully over a war memorial. “Curiously”, Donoghue noted, “no one complained about us stealing their dinghies.”

Having narrowly missed out on winning a trip to England in the Battle of the Bands, the Dizzy Limit negotiated their own return trip in mid-1970, playing their way across the world on Shaw Saville’s Northern Star and Southern Cross liners. Arriving in Britain in August, along with Stu’s wife Lorraine and five-month-old daughter Belinda, they scored a gig playing at a New Zealand Festival in Plymouth, Devon. Other acts included Kiri Te Kanawa and the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra.

Other gigs were less prestigious. Frits, Steve and John rented a flat in Cricklewood and arranged for the group to play at the local Cricklewood Castle pub. They found that The Fourmyula were living walking distance away in Willsden Green. Their compatriots, though living on mince and rice, must have been faring slightly better than they were, demonstrated by the fact that they had all the latest records.

“We were too poor to buy records,” John Donoghue remembered. “But the record companies used to put out compilations called samplers, which were quite cheap. One day Steve bought home a CBS sampler which had a song on it called ‘Come to the Sabbat’, by an English Band called Black Widow. It was a standout track on the album and instantly we started learning it to play in the band.”

By November the band was sailing home. Looking to refresh their image, they changed their name to the more earthy-sounding Timberjack and, on returning to Wellington, recorded a version of the Black Widow song they had been so taken with. This gained more traction than the previous singles and became a finalist in the 1971 Loxene Golden Disc Awards. Once again, a video was produced and, once again, it was banned from television.

The blood-thirsty clip for ‘Come to the Sabbat’ jammed the NZBC switchboard with complaints

On the Memories of New Zealand Musicians website, Stu Johnstone recalls: “The promoters of the awards choreographed and organised the filming of a blood-thirsty video of the band carrying out a ritual stabbing of a naked woman. The first airing led to the [NZBC] switchboard being jammed with complaints and a bunch of critical letters to the editors of newspapers nationally. To our surprise the clip was rescreened a week later, this time in negative (with the blacks and whites reversed out), making it look even more unsavoury and leading to a second outcry and a total ban.”

Though ‘Come to the Sabbat’ gave the group its highest profile in a seven-year career, the four members were starting to pull in different directions and by the end of 1971 had called it quits.

John Donoghue had developed as a prolific original songwriter and would go on to record several solo singles and two albums for Ode. For some of these releases he used the name Timberjack Donoghue, after being persuaded by O’Neill-Joyce that the association with the band would help sales. His first solo album, 1973’s The Spirit Of Pelorus Jack, was released solely under his own name, but he reverted to the Timberjack Donoghue moniker for his second album, the 1975 Donoghue. He would go on to play with Human Instinct, the Mangaweka Viaduct Blues Band and The Warratahs, among other groups. John died on 9 February 2024.

Steve McDonald played in various pub bands during the 70s including Distillery, before developing a solo act specialising in his own style of Celtic music with synthesisers and vocals.

Frits Stigter went on to play with The Quincy Conserve and Redeye through the 70s, and continues to play in popular Wellington covers band Livewire.

After a few years playing bass for a folk-rock trio in Wellington, Stu Johnstone effectively retired from music, shifted to Auckland and concentrated his energies on a career as a share broker and investment banker. But in the early 90s he began playing jazz with Trevor Thwaites’s Prohibition Big Band and taking double-bass lessons from Kevin Haines. He also took classical bass lessons from Alberto Santarelli. In 2005 he enrolled at the MAINZ music school and graduated the following year. He continues to play jazz and tutor in music technology.

Kelvin Diedrichs continued to play around Wellington until the early 2000s when he moved to Australia, where he died in 2007.

--

Thanks to the Andy Shackleton estate and the archived version of his NZ Musos website.