The 1980s and the 1990s were the decades when New Zealanders finally decided that our popular musical past was worth exploring, preserving and documenting. It was the decade of several key works, not least John Dix's ground-breaking Stranded in Paradise, which said it was ok to like and even obsess over our rock and roll past. And then we had a brace of books by Wellington drummer Roger Watkins, which detailed the bands that made up the scenes in both Wellington (his first, When Rock Got Rolling, published in 1989) and Auckland (Hostage To The Beat, 1995) were both detailed and fascinating, and proved that few bands with a live following were too insignificant to cover. The books provided a source of inspiration for AudioCulture and are now – long out of print – very much in demand and hard to find.

AudioCulture asked Roger Watkins to detail his path to the books.

–

I was living in Adelaide when I saw a TV documentary called “Australian Music Stars of the 60s”. What surprised me was the number of New Zealand musicians and singers who were featured – Mike Rudd, Johnny Devlin, Max Merritt, Dinah Lee, Johnny Dick and many others whose names I now don’t recall – even the host of that flagship Australian music show Bandstand, Brian Henderson, was a New Zealander. It amazed me that the Australian broadcasters had enough foresight to preserve so much of these programmes dating back to the sixties. In New Zealand, very little footage remained from the few pop music shows that had been made here – In The Groove, Let’s Go!, or even C’Mon and Happen Inn.

Dinah Lee and Roger Watkins at the National Library in Wellington, April 1995. Dinah was gifting her archives to the library.

If you read any of the “legitimate” history books about New Zealand, popular culture gets short shrift. It is hardly acknowledged. I’d been living in New Zealand for many years, was a working musician but knew very little about the size or scope of the scene here that developed in the wake of the moral panics that exploded with the revelations of teen misbehaviour in the Hutt Valley and the Parker-Hulme murder trials (the subject of Peter Jackson’s 1994 film, Heavenly Creatures) and led to the publication of the Mazengarb Report. In effect, popular culture was not valued here despite overwhelming evidence of the impact it had on life in this country.

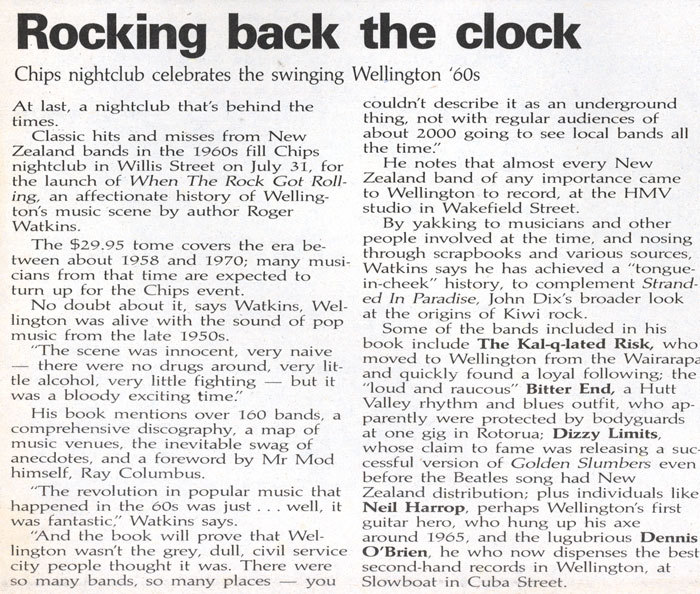

The 1989 book launch for When Rock Got Rolling

Seeing that show in Australia got me wondering, and on my return to Wellington I began to explore the idea of exposing the magnitude of the pop scene here from its early days through the fab sixties and beyond.

It soon became clear that there was essentially very limited footage available from TVNZ – the original tapes had been re-recorded over because of the costs of archiving. Certainly there was insufficient to create a TV series or even a decent half-hour programme.

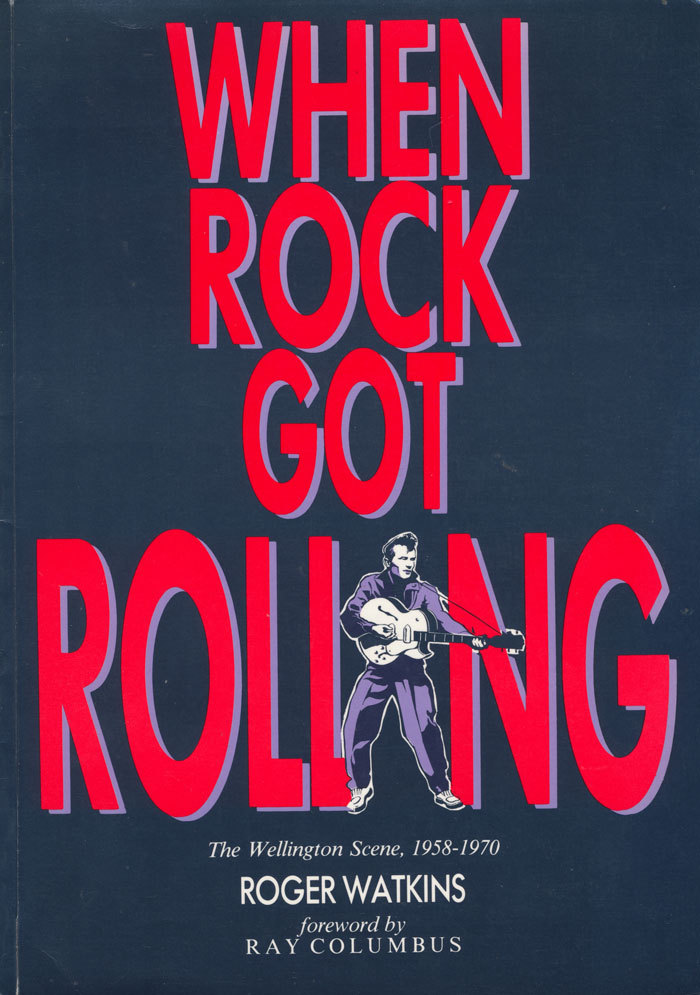

When Rock Got Rolling, published in 1989 by Hazard Press, with a foreword by Ray Columbus

At that time, there were no books at all that had been produced here that told the story of our pop revolution or its impact on life. So I decided to compile a collection, a book, something that would demonstrate the incredible depth and reach of pop music created by local musicians and singers in the cities and provincial centres here. It soon became clear that it would be a monumental task, so I decided to focus first on Wellington, with the intention of documenting other centres progressively. I also decided to begin with the pioneering acts of the late 1950s and follow through to 1970, which is when, to me at least, the scene became much more international in flavour and aspiration.

Of course, I only managed to compile the Wellington and Auckland books, but I’m proud of them and the enthusiastic reception they received. Life and the demands of earning a living for my family meant plans for other projects had to be shelved for the time being.

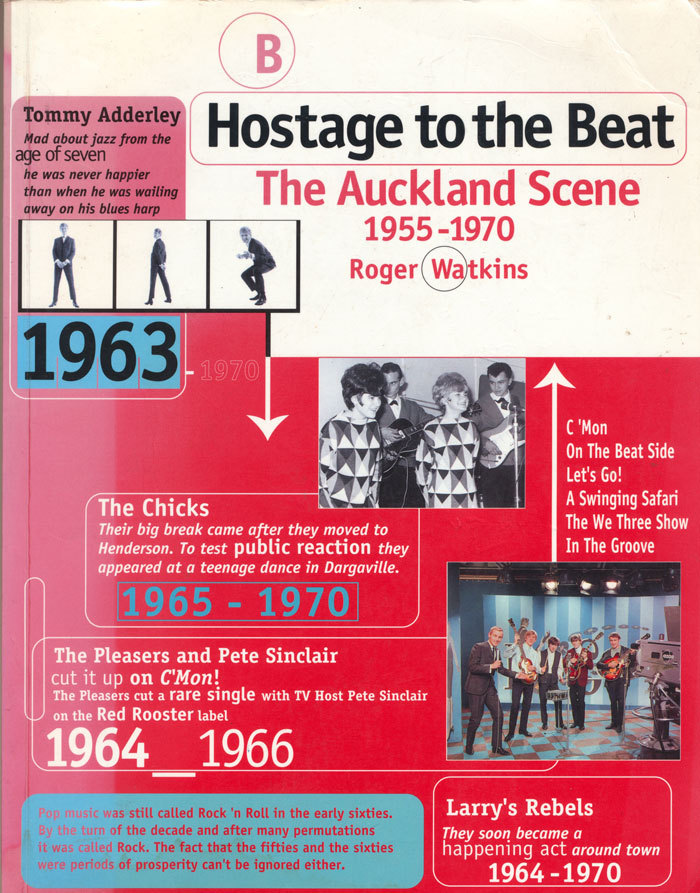

The second volume in Roger Watkins' series Hostage To The Beat, published in 1995 by Tandem Press

All I wanted to do was demonstrate, in as simple and direct a way as I could, by use of photos and discographies, just how huge the New Zealand scene was. I hoped that having seen the evidence, and recognising the follow-on evolution of youth related business activity like fashion houses, magazines, night clubs, marketing advances and even the ability of local musicians to earn a living at playing music full-time and no longer have to have a day job, that “legitimate” historians might take that into account when writing about New Zealand culture and history in the future.

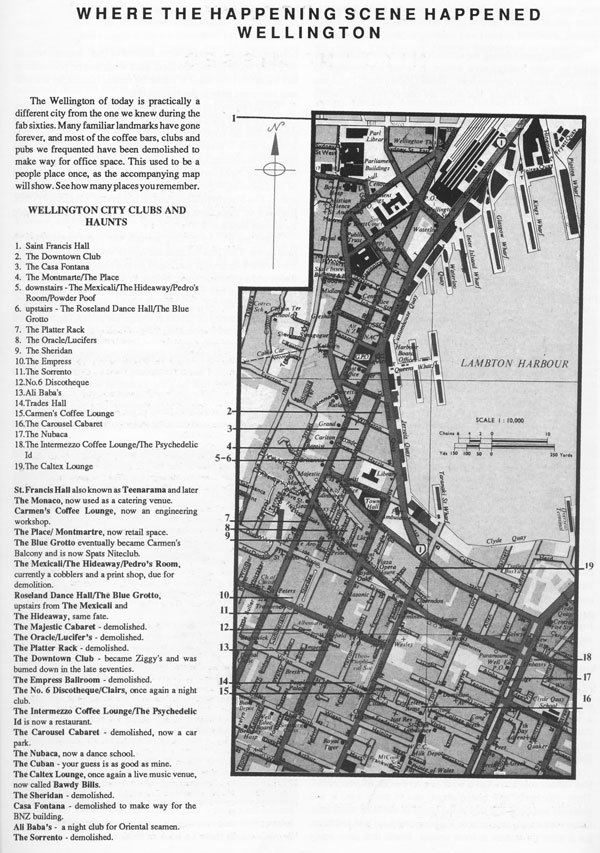

Wellington clubland in the 1960s as featured in When Rock Got Rolling

Culture should not be limited to opera, classical music and theatre. No other cultural activity, not even rugby, has had the impact that pop music has had, and I strongly believe that our stars deserve to be recognised and remembered for their achievements and the impact they have had internationally, both as stars in their own right or as sidemen in famous bands from other countries. Others have now written about those people, and it’s great to see that there is a growing appreciation of the amazing heritage our older musicians have left us, both in recordings and stories of their lives on the road.

Roger Watkins at National Library in April 1995 with Dinah Lee

For me, popular culture in all its colourful variations is an essential chapter that must be included in the story of New Zealand in the 20th century. To a large degree, it more sharply defines who we are, how we got to where we are, what we are about. Pop and rock in its various guises enables us to voice our political views, our social values and to tell our story for all to see and hear. It’s now a very small world, after all.

–

All images courtesy of Roger Watkins