With the sudden death of Mick Sibley from an aneurysm in November 2014, drummer Ian Thomson found himself the sole survivor of The Dark Ages line-up that nearly 50 years earlier had recorded their legendary ‘Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day’ single.

Bandmates Darryl Keogh and Vaughan Stephens both died young in the 1970s – Keogh in a road accident, Stephens in Carrington Hospital after a battle with drugs – and singer Clive Coulson, who went on to work with Led Zeppelin and to manage Bad Company, died of a heart attack in 2006.

Thomson survived a heart attack and triple bypass surgery in 2003 and is now as busy as ever in his own blues band, The Flaming Mudcats, with the same joy and enthusiasm he brought to that Dark Ages session half a century ago.

He believes the magic of ‘Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day’ ... is the reckless abandon with which the teenagers attacked the song.

He believes the magic of ‘Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day’ that sees it still heavily sought after by collectors – with sellers able to command more than $200 a copy – is the reckless abandon with which the teenagers attacked the song.

“It’s real rough and it was never, ever doctored. We were young guys and we didn’t have a lot of skills,” Thomson said. “We just wanted to go and belt the shit out of it and just play the bloody thing, and that’s what we did.

“What it actually does do is it captures the sound and the rawness and the guts of a garage-type band and some guys playing it hard out, having a whole lot of fun and just giving it shit.”

Ian Thomson sat down with AudioCulture to talk about his recollections of recording that single and the story of The Dark Ages, whose lifespan was a little more than a year – all over by the time most of the band were 17.

For Thomson, the first connection was made in 1964 in the fifth form at Penrose High School when he and bass player Vaughan Stephens put together a band for a school talent quest, which they won performing ‘Peter Gunn’.

“Vaughan was a serious musician, a quiet, sort of reserved guy. He was a little bit of a troubled soul but he was hugely intelligent and he seemed to hear about this (wild) music long before anybody else. I don’t know how he knew that.

“He had a peculiar way of playing. No other bass player that I know has ever played like him. I guess Vaughan’s attribute he brought to the band was the avant-garde thing. He dressed differently and some people even copied him.”

The boys left school at the end of the year and Stephens turned up with his soon-to-be-brother-in-law Darryl Keogh, a guitarist, at Thomson’s parents’ home to ask if he’d like to join a band. Thomson had been playing in a group called The Bandits with older Māori musicians who worked with his father.

“I was always impressed with Vaughan’s bass playing, his knowledge and his enthusiasm and uniqueness. He was so totally different from anybody else I’d ever met,” Thomson recalled. “So I said yeah.”

Soon after, he attended a practice at singer Clive Coulson’s with Stephens, Keogh and guitarist Mick Sibley. The two or three songs they tried went well and the boys decided they could work together.

“What I didn’t realise at that time was it had been John (Mike) Donnelly’s gig, and he never, ever let me forget it for many years to come,” Thomson laughed.

During an earlier musical appreciation class at school, Thomson had taken along a 45 of The Rolling Stones’ ‘Not Fade Away’. “To me it was one of the wildest things I’d ever heard. So I wanted to play that stuff and here were some guys that also did and they had some other stuff that I didn’t even know about.

“It was very, very, very exciting because there were no bands around at that time doing it. There were certainly bands around that were forming at that time, but it was basically English R&B – early Stones, The Downliners Sect.”

The Dark Ages’ first gigs in the city were at the Bel Air due to the fact that Stephens and Keogh knew someone who knew the owner. When Coulson, who had a knack for PR, went and visited Top 20 Nitespot owner Stan Blinkan, they were offered a lot of work there.

“First of all we played alongside a covers band called The Premiers. They were mainly instrumental and top 40 but they were very, very good. So we were the complete opposite to them. We just brought a completely new thing to the gigs around town.”

Audience members caught up in the excitement generated by The Dark Ages at different times included future pop idol Shane Hales, future Underdog Lou Rawnsley, and Chris Parfitt, future frontman for The Hi-Revving Tongues.

Out-of-town work was always a mission and when they travelled to Rotorua, the band hired a Holden station wagon and crammed themselves in along with their gear.

They arrived to a venue full of burly bushmen and were told, “You guys had better play ‘Help!’ or you’ll be needing it.”

They arrived to a venue full of burly bushmen and were told, “You guys had better play ‘Help!’ or you’ll be needing it.” The band took the threat seriously and hurried outside to learn the song.

For a gig in Whangarei, Mick Sibley, then a storeman with National Mortgage Limited, wrapped up the band’s new Jansen amplifiers in sacking and they were put on the Road Services bus for the slow journey north.

It was back at the Top 20 where Viking Records’ Ron Dalton approached the band to record the Tommy Boyce/ Steve Venet song ‘Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day’. They borrowed Sibley’s father’s A40 estate wagon and transported gear from the Top 20 to Viking Studios.

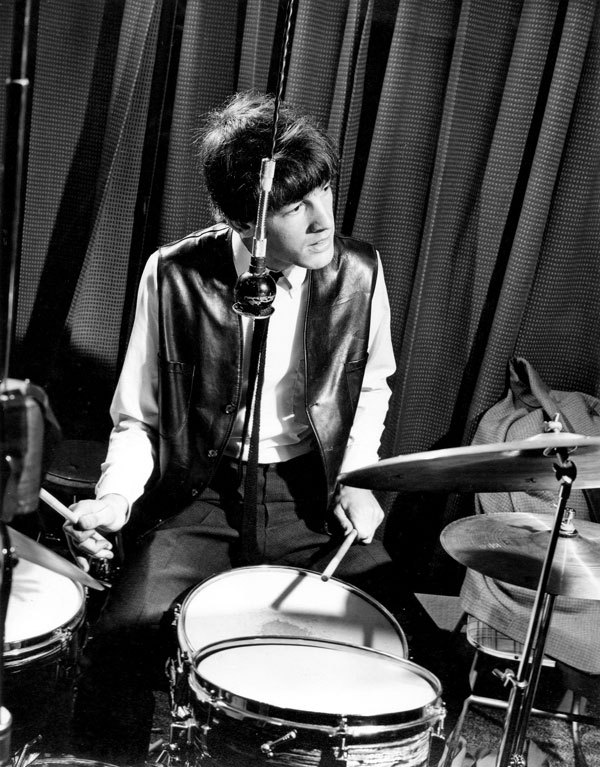

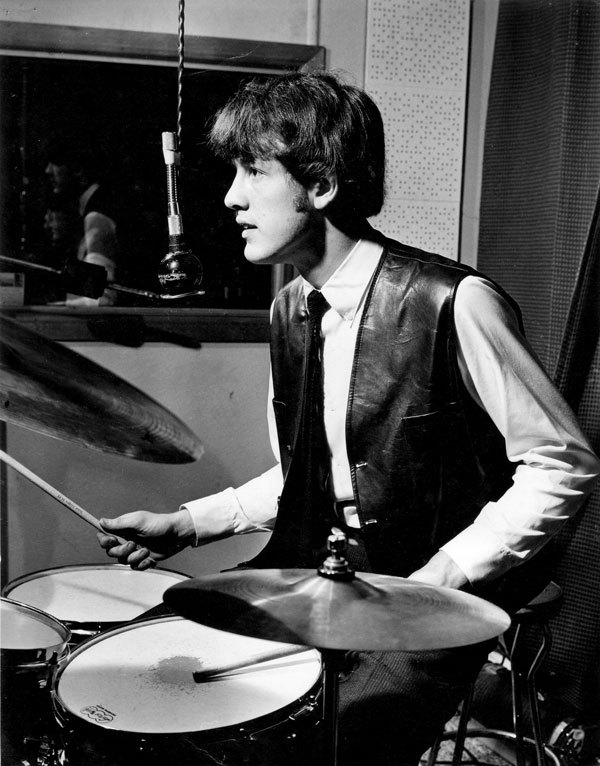

Ian Thomson at Viking Studios to record The Dark Ages’ only single, 1965

Some time was spent placing microphones in the room, but the song was recorded in one take. When asked if they had anything for the flip side, they decided on The Kinks’ cover of Bo Diddley’s ‘Cadillac’ and played it for the engineer, who liked it. “We asked if they’d like to record it now and they said, ‘We already have.’”

The Dark Ages’ most prestigious gig was when they were picked as support for PJ Proby and Dinah Lee at the Auckland Town Hall in September 1965. Both Thomson and Coulson had tonsillitis and the promoters treated the band with disdain.

“In those days they just wanted young bands to play for nothing. Kind of like what they do today, I guess. So of course we jumped at the chance to play at the town hall in front of a reasonable-sized audience.

“We got in there and the guy said, ‘Where’s all your gear?’ And we said, ‘Well, nobody said we had to have any gear. It’s locked up at the Top 20.’ So we raced down there and we couldn’t get it open, nobody was there.

“We went back empty-handed apart from guitars and they said, ‘Well, I suppose you’ll have to use the house gear of Mike Perjanik’s band.’ We played maybe four songs but it was a hell of a buzz – we opened for a full town hall.”

Not long after, Darryl Keogh left to start a family and was replaced by an acquaintance of Stephens’, Red McKelvie, who had been playing guitar with The Chelsea Beats.

“Darryl was a wild child, but he was just that shade older than us and you never really got to know Darryl too well. I wish I could have got closer to Darryl. He had a lovely wife and a baby on the way, and that was just so foreign to guys like me. It was no surprise when Darryl left, but he certainly was part of that wild look we had.

“When Red came in he was already a hell of a player and he made a difference. Darryl was essentially a rhythm guitar player, but very soon Red and Mick traded leads. In fact, Mick became a really, really good harmonica player, so that really complemented what Red was doing.”

‘Tomorrow’s Gonna Be Another Day’ was eventually released on Viking’s short-lived Red Rooster label but made no real headway and The Dark Ages broke up after a gig at the Top Cat in Tokoroa in early 1966.

“We walked into the Timberlands Hotel and, just like the cowboy movies, the whole place went quiet. It was full of short-back-and-sides, big, huge, muscly bushmen and in no uncertain terms we were told to get out or else it could be trouble for us.

“So then we tried to get somewhere to eat and nobody would serve us. We just went to the nightclub and set up, and we hadn’t eaten, nothing to drink.

“We got chased out of town because some of the local girls took a shine to us. The boys were waiting for us as we loaded up out the back and we were chased out of town being pelted with bottles and all sorts of stuff.”

By the time they arrived back in Auckland, The Dark Ages were no more. Ever conscious of a good PR spin, Clive Coulson planted a story in one of the papers announcing the split, which was attributed to Thomson leaving and the rest of the band opting not to continue.

“I think we were just all fed up. It was just a natural explosion really but, to this day, I can’t recall what it was about. It may have been about petrol money, and we probably didn’t get paid for the gig.

“We were all at the point where nobody really wanted to persevere with it anymore. Vaughan hadn’t quite married but I think he had a baby on the way, and there was just a shift of dynamics.”

Thomson and Mick Sibley joined The Underdogs for nearly a year until there was a move to replace Sibley with Murray Grindlay. “I said, ‘Well, if Mick goes, I go.’ So I left, Tony Walton came in and they made it famous.”

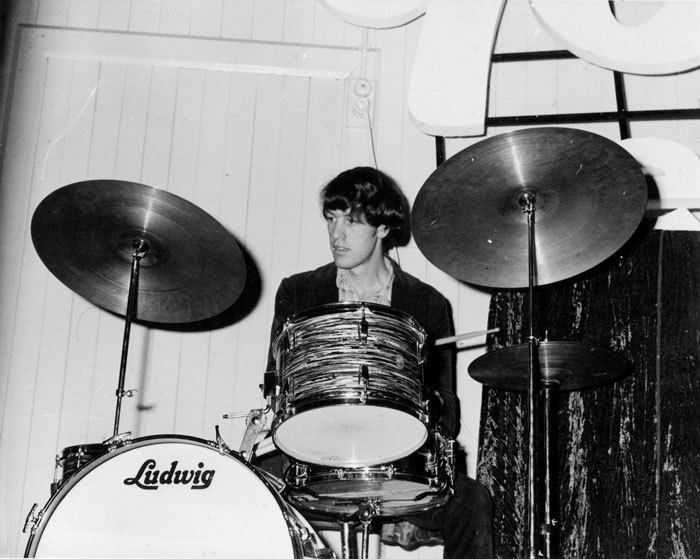

Ian Thomson at the GoGo Centre, New Plymouth, with The Underdogs, 1966

Thomson spent time in The Brew and another version of The Underdogs before finding a full-time job at the New Zealand Post Office, getting married, building a house, having a family and leaving the music scene behind.

He got back into playing in the early 1980s when Post Office trainee and future Te Vaka leader Opetaia Foa’i invited him to jam. After a chance reunion with former Dark Ages bandmate Red McKelvie at a 40th birthday party he joined McKelvie’s functions band.

Following stints in the bands of Truda Chadwick, Sonny Day and Gary Harvey and time off recovering from his heart attack, in 2009 Thomson put together his own dream band The Flaming Mudcats, who have since released two albums.

Ian Thomson with The Flaming Mudcats, Hotel Bristol, Wellington, 2013 - Photo by Don Laing

All black and white images from the Ian Thomson collection.