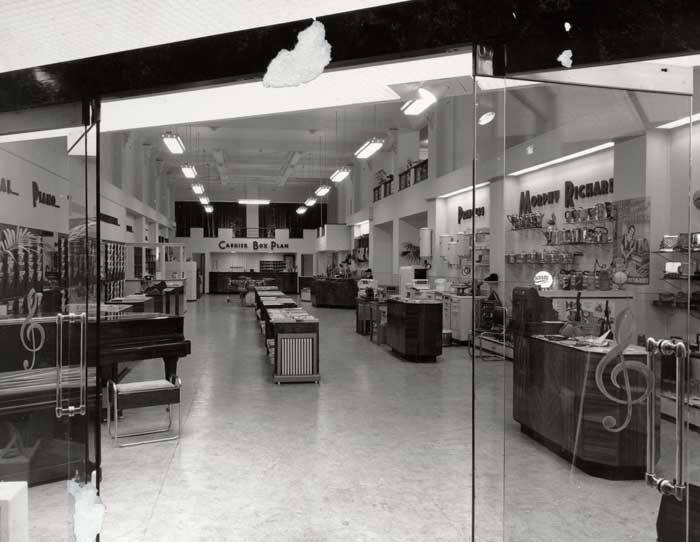

The HMV store on Courtenay Place, Wellington, c. 1960, showing the array of products the company manufactured and distributed. Among the artists with LPs on display are Nat King Cole, Vera Lynn, Benny Goodman, Bill Haley, plus soundtracks and musicals. Perhaps a radiogram, suitcase turntable or fridge to go with that? At the National Library website this photo can be enlarged to explore the detail. - Photo by K E Niven & Co; 1/2-210554-F, National Library of New Zealand

At the height of the swing era and the Depression in the early 1930s, Wellington’s alligators – white jazz musicians – gathered on Friday afternoons at 69a Manners Street. This small musical instrument store, not far from the city’s large Begg’s branch, was run by Jack McEwen, saxophonist with the Allen’s Orchestra dance band. (In a noir-esque touch, it was also a front for a money-lending firm, City Finance.)

Several of the city’s dance musicians – among them broadcaster Arthur “Turntable” Pearce and his radio boss Bob Bothamley – often met with McEwen and others to open a few ales while gathered around a gramophone to analyse the latest jazz 78s from the US. The after-hours sessions were more for jamming than listening; the musicians played along to records by acts such as Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong.

In 1936 Vanvi’s – one of the city’s longest-lasting record stores – opened nearby at 91 Cuba Street. Owned by menswear retailers Mr Vance and Mr Vivian on capital of £1000, it intended to sell, repair, and manufacture radio equipment and “cinematograph and talking machines”. But Vanvi’s operated like a record store in the modern sense: the discs weren’t a sideline to whiteware. It would later be bought by HMV (NZ) Ltd, and in the 1960s among its staff was Colin Morris.

For most of the 20th century, the area within and nearby Manners and Cuba streets was Wellington’s music precinct, with stores such as Begg’s, Nimmo’s, The Golden Horn, and Shand Miller’s, mostly dealing in instruments and sheet music. From the 1970s to 2000s they were joined by Chelsea Records, Sounds and other record retailers.

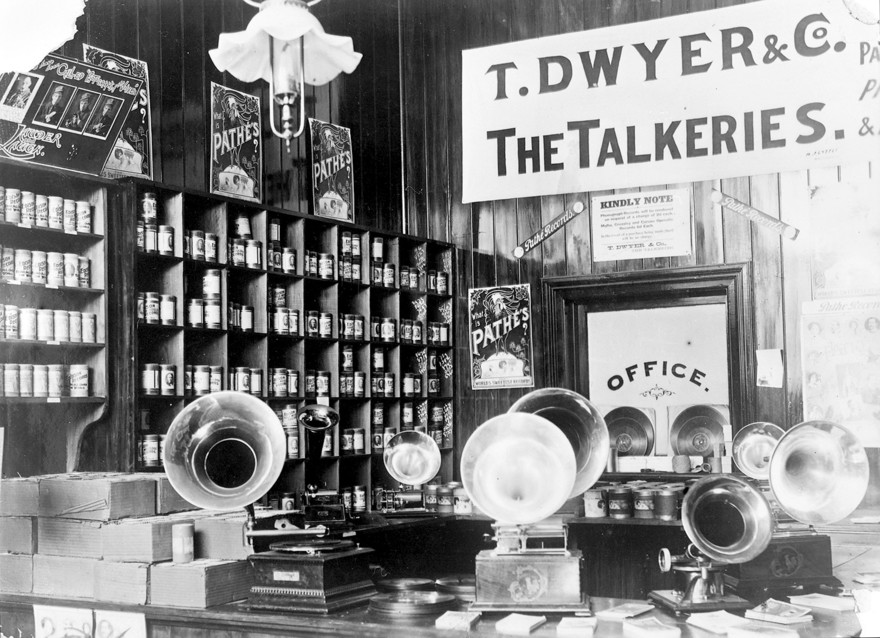

Cans of beans? No: Edison cylinders. Interior of the Masterton branch of The Talkeries cylinder and disc store, c.1909. - Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-043062-F.

Wellingtonians first witnessed a record player in 1891, in a public demonstration of an Edison cylinder machine in the Opera House. By 1898 a record parlour opened in the city to sell the cylinders, and two years later a representative of the Gramophone Company in the UK visited Wellington looking for agencies to sell its recorded music. In the years before talking pictures and radio, a popular way to hear the latest releases was at public “record concerts”, where people would gather in a hall to listen together to recorded music. During the Boer War, film evenings would also feature musical items from soloists and a phonograph.

As well as making their own music, New Zealanders increasingly enjoyed listening to recordings of the world’s greatest talents. Record stores were widespread, with chains such as Begg’s, the Talkeries shops, the Dresden Piano Company, and the Anglo-American Music Stores selling cylinders and discs, and the windup machines on which to play them. The Talkeries chain was founded in 1901, with stores in many main centres such as Wellington, Masterton, New Plymouth and Dargaville. While the availability of recorded music would lead to a decline in domestic music-making, selling musical instruments was the core business for Begg’s, and a side-line for the Talkeries chain.

Begg’s came to Wellington in 1897 when it bought a business run by a Mr Cimino on Willis Street. In 1914 the company built its Manners Street shop, which became the city’s hub for instrumentalists’ needs for nearly 65 years (in 1980, with new owners, it moved to a new building on nearby Bond Street.)

No attempts at 'Stairway to Heaven', please. Begg's music shop, Manners Street, 1960. - Alexander Turnbull Library, PA1-q-110-18.

In July 1914 the Wellington branch of Begg’s music store was advertising ragtime records for 3/6; among there were ‘Everybody’s Doing It’, ‘Gaby Glide’, ‘The Wriggly Rag’, and the ‘Turkey Trot’, and vocal numbers by Nellie Melba, Clara Butt, Peter Dawson, John McCormack and others.

Legendary Scottish music hall entertainer Harry Lauder was on tour in New Zealand in the first weeks of World War One. In Wellington, he was treated like a “royal potentate”, and he was serenaded into the Opera House by a pipe band each evening of his six-night season. Tickets were up to 7/6, and his fee was reportedly £1000 per week. An innovation was the simultaneous availability of Lauder’s latest, double-sided records in Wellington stores; among them were ‘Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep’ and ‘Stop Your Tickling, Jock’.

The Anglo-American Music Stores had branches in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. Their approach to sales was aggressive: they advertised widely and regularly marked down their product range. In 1914 they advertised that 1000 watches, necklaces, chains, medals and gramophone records would be given away free at the Wellington store, at 116 Cuba Street. The company exploited the ragtime fad, emphasising its wide stocks available at 6d per song. In 1914 the chain’s Wellington branch advertised several new songs by Irving Berlin, then dominating the sheet-music market. For 1/6 pianists could buy Berlin’s ‘When the Midnight Choo Choo Leaves for Alabam’, ‘Stop! Stop! Stop!’ and ‘Come Over and Love Me Some More’, as well as a saucy summer hit for the Australian swimming star Annette Kellerman: ‘Come Take a Dip in the Deep With Me’.

Anglo-American’s owner, the splendidly named Douglas V. Lillicrap, was successfully sued in 1918 by Australian music publisher Albert’s for selling ‘They Made it Twice as Nice as Paradise, and They Called it Dixie-Land’ without holding the rights.

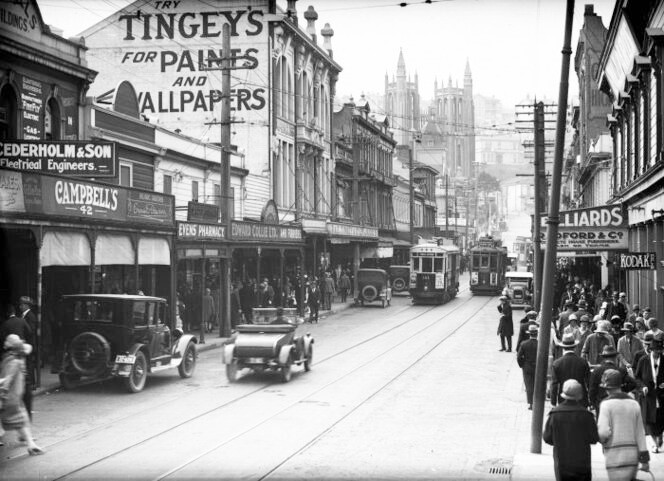

Manners St, Wellington’s music hub for decades, in 1928. Ernest Dawson’s record store was at No. 40, on the far left. - Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-047578-G.

There were many complaints in 1920 when the price of new records was 100 percent higher than they had been prior to the war. It wasn’t profiteering by the retailers, insisted one store manager to NZ Truth, but increases in the manufacturing costs: shellac had gone up from £35 per ton to £800 per ton. Also, salaries at the Zonophone and His Master’s Voice Company had risen £20,000 in one year.

Ernest Dawson’s, “a gramophone and record specialist” at 40 Manners St, offered a new service from its opening day on 26 September 1924. Gramophone owners were invited to visit their music rooms: audition spaces in which “you can hear records in quiet, in private, in comfort. You can then make sure that you buy only those records which thoroughly appeal to you.”

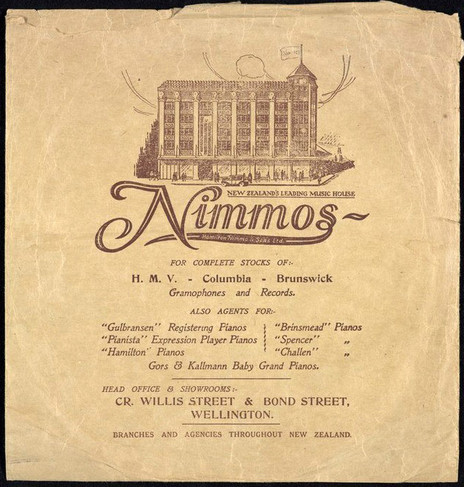

A record bag from Nimmos, early 1930s - Adam Miller collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Eph-C-PHONO-Miller-N-01

Nimmos was one of the city’s leading piano retailers, and the official piano supplier to the governors-general. It expanded into radio and record retailing in the 1920s. Its founder Hamilton Nimmo built the imposing art deco tower in 1929 on the corner of Willis and Bond streets, where it still stands. In 1931 the firm became one of several music stores that secured a radio licence (2ZW), but this was short-lived as the government nationalised broadcasting in 1933.

The Nimmos building also contained a concert hall from which, on Tuesday nights, the Plume Melody Makers dance band would broadcast a three-hour live show on 2ZW. The Wellington Swing Club held its first public meeting in the Nimmos Hall in 1946, and its weekly sessions provided a place for swing aficionados to meet and listen to the city’s leading players perform without the distraction of dancing, and to talks by experts such as its president, Arthur Pearce. “It builds into a real jam session,” reported the NZ Free Lance. “Dancing is taboo: the people who attend go to listen, analyse, criticise and appreciate.”

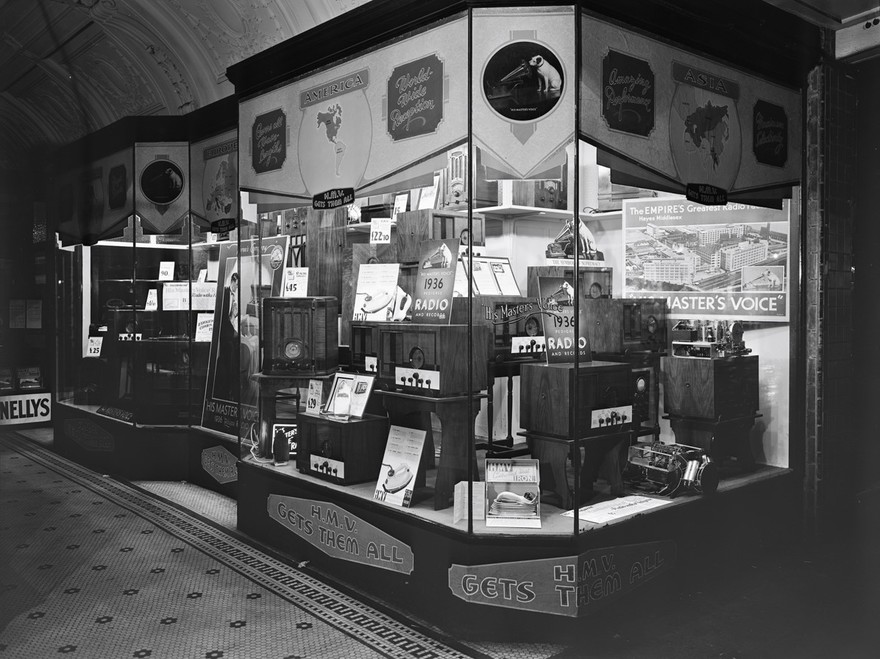

"The Empire's Greatest Radio Company": HMV (His Master's Voice) music shop, 91 Cuba Street, Wellington, 1936. - Ken Niven, Gordon H. Burt Ltd. Te Papa (C.00251

Record sales dipped during the 1930s, when the economic depression led people to find free music via another new medium – radio – which only cost the price of the receiver, and a licence. In September 1939 came another shift in music distribution, with the start of the Second World War.

“Wartime restrictions made it almost impossible to get records in Wellington shops,” wrote EMI archivist Bruce Anderson. From mid-1941 Australian pressings were in short supply, and orders from local dealers often took six months to arrive, if at all. “In Wellington the four main record shops – Beggs, Nimmo’s, HMV and Columbia House – used to offer a weekly quota of popular discs each Friday. Before midday about 100 records would be placed on the counter for the lucky ones who were able to get to their nearest shop and have first choice. By 1pm only the leftovers were available.”

During the war Vanvi’s, at 91 Cuba Street – near the entrance of what became Cuba Mall – was Wellington’s hippest record store. Among its dedicated customers was a teenage Ray Harris, future Listener jazz columnist. In 1981 he recalled to me that on Friday nights during the war “at seven o’clock they cleared the counters of what I call the rubbish and out would come a few boxes of jazz or swing 78s.” These would be the only new records for the week. Begg’s and Nimmo’s also managed to source new records, but not nearly the quantity or variety.

Met me at James Smith’s corner: Manners and Cuba Street, Wellington, 1949. For Vanvi's, turn right. For 2ZB or Columbia House, straight ahead to the Hope Gibbons Building. - Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-04890-G

People would line up outside Vanvi’s during dinner time, and once the doors opened again, anyone wanting new records would run in and “grab a pile and turn it over, and then the next guy along from you had a pile and you’d try and sneak it so you could have his pile and he could have yours and the people behind had no show.”

A woman behind the counter was the savviest person on the staff. Known only as Miss Bird, “She was the one who was knowledgeable,” recalled Harris. The male manager wasn’t nearly as helpful or knowledgeable. “She knew who we were, and what we were after.”

After the war, Harris began buying his 78s from Norman Hull-Brown’s long-standing shop The Golden Horn at 137 Vivian Street, where it had been in operation since 1902. Hull-Brown, a dance-band musician, was well-known for his enthusiasm and willingness to source hard-to-find records. (By the 1970s The Golden Horn, run by Ian Hull-Brown, was located on Cuba Street. New to Manners Street – and opposite Begg’s – was the R&R Music Centre, an instrument store run by musicians Rodger Fox and Roger Watkins. “We were the ‘pro’ shop,” Watkins recalls, “Begg’s and Shand Millers were more family music shops.”)

By 1957 the record retail industry was expanding exponentially. According to record distributor Fred Noad, New Zealand’s “disc dealers” were “rubbing their hands with glee at the boom in the record business. Companies found it hard to keep up with the demand for new discs in all genres. The boom was created by the shift to LPs for classical and easy listening music, but especially the 45rpm singles sought after by teenage pop fans. Noad said the factor that caused the biggest bump in sales was “rock and roll, the biggest money spinner the industry has ever known.”

In early 1958 the sales of singles out-numbered those of 78s. Wellington’s major stores – the Lamphouse and HMV stores – held massive sales, placing 20,000 brand-new but redundant 78s on the market at bargain prices; due to import restrictions these would become unavailable in New Zealand (record companies would soon only be able to bring in master tapes, so the discs could be manufactured locally).

Discville Modern Record Lounge, at Fear’s appliance store, 31 Willis Street, late 1950s. - Photograph by Gordon Burt, Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-037206-F.

At the time, record stores were flourishing along Wellington’s “golden mile”, from Lambton Quay to Courtenay Place. Those hunting for vinyl LPs and 45s – and the quickly disappearing shellac 78s – could walk from the Cenotaph near Parliament to the Embassy at the end of Courtenay Place. Along the way they could visit stores such as The Record Shop (102 Lambton Quay), Discville at Fear’s (“Wellington’s modern record and Hi-Fi Lounge”, 31 Willis Street), Nimmos on Willis St, Begg’s on Manners St, Dixon Maddever (at the Opera House), the Record Grotto and Coffee Bar at Gurney’s Electric Company (139 Cuba St), Vanvi’s, record bars in the three department stores Kirkcaldie’s, James Smith’s and D.I.C., two branches of the Lamphouse, as well as the main Columbus and HMV stores.

Employees of James Smith’s department store load company vehicles with Christmas orders of the hottest disc of 1958, the cast recording of ‘My Fair Lady’. - Evening Post collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, EP/1958/4262-F.

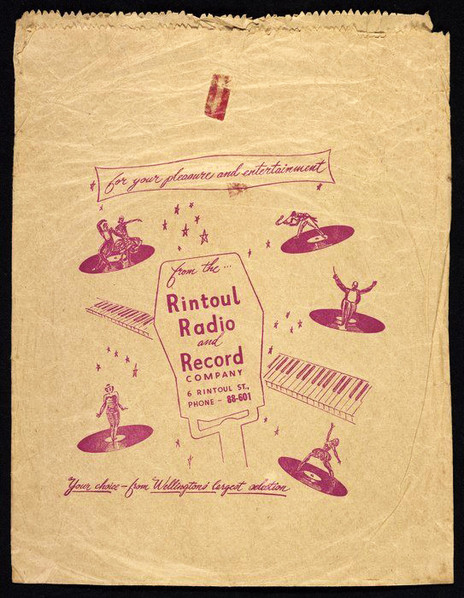

There were also small independent stores such as Musical House, run on Kent Terrace by session bassist Slim Dorward, selling piano accordions, portable gramophones, as well as classical records. Opposite it, in 1960, was the Cambridge Record and Electrical Supplies Store and, further south in Newtown, right through the 1950s a Mr Jorgensen ran a record, radio and sheet music store at 6 Rintoul Street.

Rintoul Radio and Record Co, Newtown, 1950s - Alexander Turnbull Library, Eph-C-PHONO-Miller-R-01

In December 1965 a large advertisement appeared in the Dominion Sunday Times, announcing “big news for record buyers”. The Willis Street Record Centre – an offshoot of HMV Sales & Service (Vanvi) Ltd – was about to open on Willis Street opposite the Grand Hotel. It would offer classical, imported jazz, show music, soundtracks “and all forms of popular music”. In the opening week, every customer who bought two LPs would also receive an EP or two 45s of their choice, free. Sixteen months after the Beatles had waved from the balcony of the St George Hotel, one block away, the music business was booming.

Evening Post, 12 December 1965. - Bruce Anderson papers, Alexander Turnbull Library

Half a century later, a 27-storey, black “Darth Vader” skyscraper stands on the site of the Willis Street Record Centre; the store had closed on 2 February 1973, when the BNZ tower began its drawn out, much-disputed construction. In 2020, its basement contains a branch of the last big-chain record retailer in New Zealand: the Australian-owned JB Hi-Fi. In recent years JB’s once vast selection of CDs has shrunk to make room for bins of new 180gm LPs: “vinyls” to a new generation. On the edge of the old music precinct, Cuba Street’s legacy is kept alive by Dennis O’Brien’s Slow Boat Records, and Paul Huggins’s Rough Peel Music.

--

Other pioneering Wellington record stores:

The Berkeley, 101 Manners St; Chivers Music and Phonograph Stores, 17 Lambton Quay, also at 34 Willis St; Columbia House, Dixon St, beside the Hope Gibbons Building; Columbia Sales Co, Lambton Quay (“next to the Kelburn Tram”); Fleming & Co, “The Phoneries”, 91 Riddiford St, Newtown; Will Gordon, 286 Lambton Quay, Wellington, also at 48 Main St, Lower Hutt; The Gramophone Record Exchange, Lombard St; Haworth’s Music House, 109 Cuba St; W L Jenness, 143 Jackson St, Petone, also at High St, Lower Hutt; Lewis’s Music Store, 89 Cuba St; Fred Matthews, 34 Willis St; Nimmos, cnr Willis & Bond Sts; F J Pinny, Willis St; The Talkeries, 24 Willis St; Turner’s Music Store, 34 Willis St; Walters’ Gramophone Hospital, 57 Vivian St.

--

Read: Wellington’s Lost Record Stores – a personal introduction

Read: Wellington’s Lost Record Stores 1 – the Golden Mile

Read: Wellington’s Lost Record Stores 2 – burbs and back alleys

Read: Silvio’s – the accidental record store

--

Thanks to the Old Wellington Region Facebook page for finding the HMV photo.