It’s night time in the big city. A heartbroken man walks the drizzly footpath. A copy of ‘In the Wee Small Hours’ awaits him. Courtenay Place, Wellington, 1950s. The Lamphouse is second on the left. - Photo by Tomson Garland, courtesy Amanda Garland; copyright.

Exploring Wellington’s leading record stores in the golden era of retailing.

Lamphouse

As the name suggests, Lamphouse did not regard selling records as its primary business. With branches in Manners St, Courtenay Place, Cuba St, Lower Hutt, Naenae, Upper Hutt, Tawa, Porirua, and Levin, the chain specialised in lamps and all manner of electrical goods, yet it played a good part in the education of some of Wellington’s future musical stalwarts.

Chris Parfitt, singer with 1960s hitmakers The Hi-Revving Tongues, remembers frequenting the Naenae store from his early teens. “It used to play Herma and The Keil Isles a lot: ‘The Twist’, ‘A Quarter to Three’, ‘If You Wanna Be Happy’, ‘Cherry Pink’. It also had a TV set on display before there was TV, but we still used to stand and watch it!”

Music writer David McLennan also recalls the Naenae store. It was where he bought his first record, age 15, Hogsnort Rupert’s ‘Gretel’. Crocodiles founder Fane Flaws had his first holiday job behind the counter at Lamphouse’s Courtenay Place outlet, where most of his pay packet would be spent on records before he’d finished his week’s work.

Lamphouse bag.

As well as stocking the latest popular titles, Lamphouse had deep sale bins of both LPs and 45s, which could be a treasure trove for anyone seeking more obscure sounds. A teenage Dennis O’Brien, who would later open his own Slow Boat Records, was one such habituée. He fondly recalls such finds as Garnet Mimms & the Enchanters’ Cry Baby and 11 Other Hits, an American pressing.

“Lamphouse in Manners St was excellent because it had sale bins and if you’re looking at 1963-64 when you got half a crown a week pocket money [2/6] and couldn’t afford a 39/6 LP you’d go in and find stuff for 19/11 or 16/7 or something. So that’s where I’d occasionally buy LPs. But I went in one day in my St Pat’s uniform and there was a fellow that used to work there named Don Richardson, a jazz guy, and to the amusement of his fellow workers he started up on ‘Hello Dolly, it’s so nice to have you back where you belong …’ and I felt very embarrassed, because I was in there all the time.

“I was very quiet and didn’t speak to anybody and they obviously thought I was some sort of schnook, as we would have it then. I always held it against him because I knew it was aimed at me.”

Records Preservation

Records Preservation sticker. - Adam Miller collection, 78rpm.net.nz

Records Preservation and Book Palace was possibly the first secondhand record store in Wellington, with stores at different times in Kent Terrace and Riddiford St, but situated for most of its existence at 191 Cuba Street. It was started in 1966 by Terry Lahogue, who was joined in the 70s by his son Mark. Mark recalls a colourful array of customers, partly due to the shop’s proximity to Vivian Street, in those days the “red light” district of Wellington. Carmen, the notorious drag performer whose International Coffee Lounge was just a few metres away from the shop, was a frequent caller, as was the poet Sam Hunt. The business was eventually bought in 1985 by Dennis O’Brien and the Cuba Street address became the second location of Slow Boat. Dennis remembers Terry Lahogue’s advice to “never sell anything that you don’t make a buck on and only hire your family because everybody else will rob you blind.” The Lahogues moved to Fremantle in Western Australia where Mark opened The Record Finder and continues to specialise in good quality used vinyl. Terry, now in his late 80s, still helps out in the store.

Silvio’s Used Records

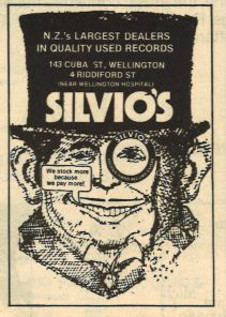

Advertisement for Silvio’s, in Cuba St and Newtown: Rip It Up, February 1978.

A legendary secondhand store in the 1970s and 80s, with an unforgettable character at the helm. At all of his shops’ locations – Newtown, Willis St, and most prominently in Cuba St – Silvio Famularo was usually behind the counter, wiping with a damp cloth the surfaces of some recently purchased LPs while singing an operatic aria, apparently to himself, though anyone entering the shop inevitably became his audience. In early 1977 the store moved to its best known spot, 143 Cuba St. “It became a meeting place,” Silvio remembers. “You’d come into the shop on a Friday night and there’d be a big crowd there. Plus the fact that people came regularly because there were new records every day.”

This much-loved destination for pre-loved grooves demands its own profile on AudioCulture. To read the full story, go to Silvio’s: the accidental record store.

Colin Morris Records

Colin Morris - Yellow Pages listing, 1985.

The doyen of Wellington record retailing requires his own profile to cover the 50 years he has been selling and promoting music in the city. Colin began at Vanvi’s in 1965, worked at Tiffany’s, and from the mid-1970s owned and ran several stores in different locations throughout the CBD. Recalled Fane Flaws: “Colin raised the bar in every way. You could talk to him about the most esoteric musical shit and he didn’t blink – he was already up with it!”

For a roller-coaster ride through record retailing, with walk-on cameos from Muddy Waters and BB King, go to AudioCulture’s Colin Morris page. Meanwhile here are Colin’s ...

20 Solid Gold Favourite Customer Requests

“At these prices, how come there aren’t two records in here?”

“Are there any other record stores around here?”

“I can’t find your Quad section.”

“J? … I was looking under Tull.”

“Do you sell 8-tracks?”

“I’m buying it for my little sister.”

“Anything by Pamela Mowtown?”

“Why, I can remember when these little records cost 4/6d.”

Plus others, and a bonus track –

Customer to friend: “Okay. You buy it and I’ll tape it.”

– Colin Morris Records promotion, late 1970s.

Chelsea Records

Chelsea Records sticker, late 1970s.

From the mid-70s to well into the 90s, Chelsea Records was one of the most visible and popular record retail brands in Wellington.

Under James Moss, the store’s connection with the Jayrem label made it a focus for local music and musicians. In the early 90s, staff included a young Jon Toogood, just setting out with his band Shihad, who would eagerly direct customers to the latest local albums by bands such as Bailter Space and Skeptics.

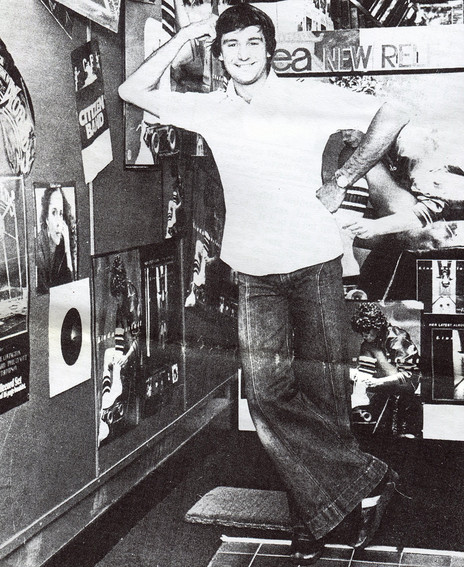

Chelsea Records was begun around 1974 by Peter Bell and introduced an aggressive style of discounting previously found only supermarkets. A popular local DJ with his own mobile disco (Moby Discs, with “fabulous lighting effects”), Bell had previously worked in London. (The shop he ran there was used in the film A Clockwork Orange, and he can be spotted near the front of the crowd in the film of the Rolling Stones’ 1969 Hyde Park concert.) With Richard Branson’s innovative Virgin stores fresh in his mind, he set out to create his own hip music retail business. A large display wall would be deeply stocked with copies of the latest major releases, all bearing a discount sticker boasting “Their price/Our price”, the latter always being considerably cheaper.

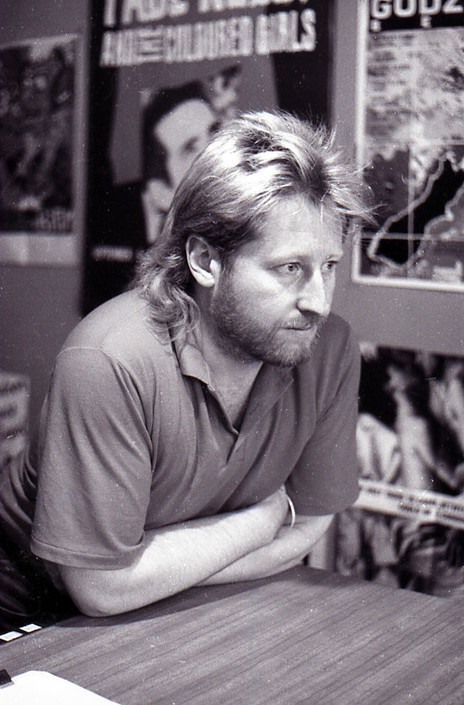

A flair for deep discounting: Peter Bell, founder of Chelsea Records, Wellington, 1978.

Bell’s original store was in Plimmer’s Emporium on Plimmer’s Steps, which also housed the trendy Toad Hall café and Printed Matter, Alister Taylor’s underground bookshop, but his ambitions quickly outgrew the space. First, he moved to a narrow-fronted shop in Manners Mall, then to a larger premises just a few doors away at 108 Manners St. This store’s grand-slam opening in 1978 saw Bell declaring it “the largest record shop in New Zealand” with “over 80,000 albums in stock”. By this time Chelsea also had a store at 209 Lambton Quay.

In 1979, in a bid to increase his buying power and discount opportunities, Bell decided to franchise the Chelsea brand. James Moss was Chelsea’s first franchisee. After a decade in the cosmetics industry, Moss had worked briefly as a marketing manager for EMI before launching his own niche marketing company RCD (Record & Cassette Distributors Ltd.) His specialist stock included reggae, blues and children’s music. One RCD-financed album Carols For Christmas sold 3,000 copies (LP and cassette). In cooperation with commercial broadcaster and children’s entertainer Lindsay Yeo, RCD sold 10,000 albums by Yeo’s alter-ego Buzz O’Bumble.

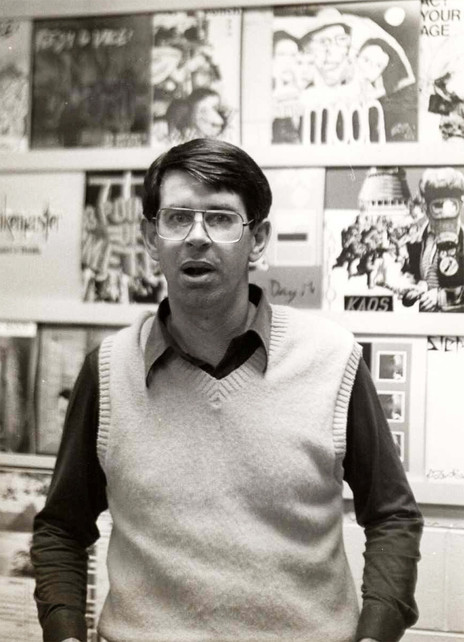

James Moss, co-owner of Tiffany’s, who bought Chelsea from Peter Bell, and later founded the Jayrem label. - James Moss collection

In 1976, Moss bought a half share in Tiffany’s Record Boutique in 200 High Street, Lower Hutt. In the same year he and Tiffany’s co-owner John Roper opened another Tiffany’s at 276 Jackson Street Petone. Until 1979 Moss divided his time between running RCD and manning the counter at one or other of the Tiffany’s outlets.

That year he bought franchises from Bell, changing the names of the two Tiffany’s stores to Chelsea and, at the year’s end, buying out Roper.

An octet of Wellington record retailers, assembled at Chelsea Records, Manners Street, c. December 1986. At the back, from left, is Evelyn, Wendy Calder (member of The Body Electric), Kevin Kane, Graham McFarlane (manager of the Lower Hutt branch) and Lane Husband. At front, from left: Brent Gleave (later of Allan’s CD store, Smoke, and Capital Recordings), Josie, and Jac Kluts (who died in 2018, after a long career as a radio executive). - Kevin Kane collection

In 1980 Bell moved to Sydney with plans to set up an Australian Chelsea chain and Moss purchased the Chelsea name for New Zealand along with the Manners Mall shop. Moss also opened a Chelsea record bar in the James Smith’s department store. He then began to franchise. By the mid-80s Chelsea was the largest record retailer in New Zealand, with 14 franchises, from Hamilton to Timaru, including the Johnsonville and Porirua malls.

Moss maintained Bell’s policy of discounted pricing but after a visit to Tower stores in the United States became convinced in the importance of stocking a broad range of albums. In the 80s, the Chelsea import bins became a goldmine for anyone interested in more esoteric names, from jazz to post-punk to world music. Serious customers would find out when the new imports were arriving and queue up outside the shop or push their way in just before closing time the night before, as the imports were being put on display.

The spacious Manners Street shop was ideal for in-store appearances, and hosted everyone from Jon English to Split Enz. The Enz promotion saw them sell 7000 albums across the Chelsea stores.

The early 80s were a time of deep social divisions which erupted violently during the 1981 Springbok tour. But the only instance of physical conflict Moss can recall in the store was during a tour of a different kind. “One of the local punks tried to bait members of Madness, who were in-store promoting their 1981 tour. Some fisticuffs resulted and I had to jump the counter to try and separate the adversaries. Meanwhile senior staff member Ron Jackson – New Zealand Commonwealth boxing rep – was giving me the big smile down behind the singles bar!”

Chelsea Records, Manners Street, Wellington, early 1986; behind the counter is John Mowatt, who also worked at PolyGram and for Jim Moss. Jayrem discs are on sale for $4.99: Body Electric (now sought after), Rick Bryant and the Jive Bombers, Sam Hunt. - Kevin Kane collection

Around that time Moss received a visit from Andrew Fagan, of up-and-coming local band The Mockers. Andrew, in college uniform, came into the Manners St store with a copy of a single he had recorded at EMI studios titled ‘Murder In Manners Street’, inspired by a real event that had taken place just down the road. “Andrew wanted Chelsea to stock his single but he had no idea what to charge for them. We thought it was a great single and sold 50 copies.”

Jon Toogood, right, while working at Chelsea Records in the early 90s. - Nikki Adams collection

Moss encouraged Fagan to approach the majors and after a couple more singles for indies The Mockers signed to RCA. But the visit provided the motivation Moss needed set up his own label, Jayrem. Having the stores certainly helped in his aggressive promotion of Jayrem hits such as The Body Electric’s ‘Pulsing’, which would spend more than half a year in the Top 50.

In 1987 Moss sold Chelsea to concentrate on his label and wholesaling business. On reflection it seems to have been the right time, just before the onset of new large chains such as ECM, Tower and Sounds.

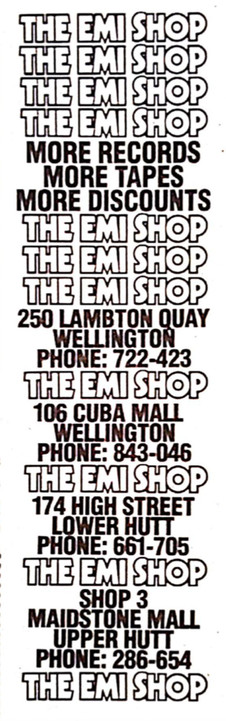

The EMI/HMV Stores

Growing up in Liverpool in the 60s, Steve Clansey developed the passion for music and instinct for promotion that he would combine in his role as manager of Wellington’s EMI stores in the 70s.

Yellow Pages listing for the EMI Shops in the Wellington area, 1985.

At 17 he became a coalminer, then worked in British Leyland’s car factory, but what he looked forward to were Friday nights when he could collect his pay and buy a record. “If you wanted a Beatles’ album you could go to NEMS which was Brian Epstein’s store,” he remembers. “But I used to go to Probe Records because they had a more interesting range of records, they imported a lot. I got to know Geoff Davies, the owner of Probe, very well. I used to end up helping him out at the weekend, behind the counter and that. I used to help him out with promotions too.”

On the weekends there were live shows: Frank Zappa or The Who at Liverpool University, Derek and the Dominoes and Leon Russell at the Polytechnic, and Neil Young and The Byrds at the Liverpool Empire where Clansey would always book the same seats (U29 and U30).

In 1973 a friend was moving to New Zealand to play football. “I said, ‘If it’s any good let me know.’ I was working at the car factory and I’d said that if they put me on the night shift, which inhibits my social life, I’d move to New Zealand.” They did, so he did.

It was a boom time for employment. As Clansey remembers: “The local paper The Dominion on a Saturday was a tome of about 100 pages and about 60 of them were job vacancies, and would say things like ‘Experience not necessary, as long as you’re willing to give us a go.’”

Festival Records in Majoribanks Street gave Clansey a go in their warehouse. Then he went to work for the larger Phonogram, centred in Wakefield Street, moving swiftly from warehouse to sales rep to label manager. It was from there to EMI, initially to manage their Lower Hutt store, then into central Wellington where EMI had taken over the short-lived Direction Records premises in Cuba Street. “But I moved into town which suited me more because I liked the music there more. The markets are different. The Hutt was singles-based, more mainstream. But I started to develop the Cuba Street store as quite an eclectic customer-based store.”

Contacts in the UK helped when it came to tracking down music customers were hearing or reading about. “These were the days of the fax machine. We used to get a big fax from Rough Trade of all the new releases. Then EMI in Australia got the Factory label so they started to release a few things, but they hadn’t got the rights in New Zealand. So one day my wife and I went for a holiday in Australia and I brought 50 copies of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures back in my suitcase, put them out in the store and after about three days we’d sold them all.”

Sticker for the import bins of the EMI Shops, 1981.

A regular Thursday night show on Radio Active – The EMI Shop Show – had obvious benefits. “If we had any new imports we’d play them on the show and people would come in on Friday and buy them.”

Promoters would sometimes call Clansey for advice. “Stewart Macpherson used to ring me up. ‘We’ve been offered so-and-so to tour, what do you think?’ He rang me one day and said ‘Steve, I’ve been offered whatever, and I was ‘Oh, a bit dodgy Stewart but you should try Talking Heads. They have just come in the charts with their first album. They’ll sell out’. And he rings me back after a couple of weeks and says ‘I’ve got ‘em!’”

To Clansey’s surprise, the famously budget-conscious promoter gave Clansey two tickets to the show. Even more surprising was when David Byrne, on the day of the Wellington concert, turned up in person at the Cuba St store, where Clansey sold him the latest Wire album on cassette.

Other store visitors included Poco drummer George Grantham, in town with former Byrds McGuinn, Hillman and Clark, who invited Clansey back to the group’s hotel where they obligingly autographed his entire collection of Byrds, Poco and assorted solo albums; and engineer-turned-auteur Alan Parsons, who was kept busy by “space cadets” answering nerdish questions about Dark Side Of The Moon.

With knowledgeable staff such as Andrew Armitage and Seamus Kavanagh (who would manage the Cuba Mall store in the 80s), EMI shops were popular destinations for left-field as well as mainstream music buyers. According to Chris Caddick, an EMI sales rep who became the last New Zealand MD, in 1980 the Lower Hutt store had the highest turnover of any EMI Shop in the country.

EMI Music Centre, 174 High Street, Lower Hutt, 1978. Originally at the Transport Centre, near Tiffany’s, in 1980 this store had the highest turnover of any EMI shop in New Zealand. The opening of the Queensgate Mall nearby in 1987 devastated the High Street shopping area, and its record stores. - Hutt City Libraries, BRN 418353

In the early 80s a further EMI Shop was opened at 250 Lambton Quay, to the dismay of Colin Morris, and by 1985 there was also a shop in the BNZ Centre on Willis Street, and another store in Upper Hutt’s Maidstone Mall. But by this time Clansey had been headhunted by paint manufacturer Taubman’s and said goodbye to music retail – though only briefly as it turned out (see Tower Music, below).

Sometime after 1985 EMI pulled out of retailing. In mid-1990 the partially EMI-owned HMV retail chain (a stand-alone division of the UK Thorn-EMI empire) re-entered the New Zealand marketplace as the HMV Shop. In Wellington the stores were located at the BNZ Shopping Centre, Willis St, there was a CD-only shop in the Lambton Square development, and others at 222 Lambton Quay, Manners Mall, and Queensgate Mall, Lower Hutt. In 1991 HMV sold its stores to the Australian chain Brashs. The Australian company’s time in New Zealand was brief, exiting in late 1992. Brashs limped on in Australia before falling into receivership for a final time in 1998.

Tower Music

Tower Music bag, 1990s. - Adam Miller collection, 78rpm.net.nz

When the manager of the Sounds store at Queensgate realised the new record shop that was about to open adjacent to his was Steve Clansey’s, he said with some relief: ‘Oh, it’s you. I thought it was Tower coming in from the States. I was shitting myself!’”

Perhaps he should have been, because Tower Music was to be one of the music retail success stories of the 90s.

While holidaying in Rarotonga, Clansey had met Jim Hall, a partner in the Wellington-based Soundtrax music production company, and the pair hit it off. Back in Wellington, Hall introduced Clansey to his teammates Callie Blood and Ian Morris (ex-Th’ Dudes), who like Hall were keen to invest in a new record shop.

Nikki Adams behind the counter at Tower Music, Wellington, mid 1990s - Nikki Adams collection

“I wasn’t working and we thought there was a gap in the market,” says Clansey. “We had a little look around and said ‘Do we want to make this a little niche store or do we want to make this worth the effort put in to get this business up and running?”

The name Tower Music hinted at the scale of their ambitions. The resemblance to the name of the American chain Tower Records was deliberate and the resulting confusion understandable, though the use was entirely legal. “We registered it here because Tower Records hadn’t registered it. And the logo was totally different.”

Callie had her friend Stuart Gardyne mock up some designs for the Queensgate store. The purple and yellow scheme shocked the Queensgate developer – ‘No, no, you’ve got to have red!’ – but a second Tower store at North City Plaza in Porirua would go on to win a design award.

Before long the new company had three more stores, in Lambton Quay, Manners St and Whanganui. “Then people started approaching us. Palmerston, Upper Hutt, Blenheim. We ended up with 12 franchise stores.”

Nikki Adams and Tower Music colleagues, mid 1990s. - Nikki Adams collection.

To maximise the cost-effectiveness of advertising, they had the idea that all the Tower stores should be situated within the same television coverage area. With Soundtrax producing the commercials (“they did the music, I did the voiceovers”), Tower waged aggressive and effective advertising campaigns.

“We did in-stores with artists. We were the go-to’s. The record companies would come to us – ‘We’ve got a new Michael Jackson’ or whatever – and we did a lot of innovative campaigns. Radio – we were on all the time.”

“Porirua – that centre when it opened was so busy. We opened it on a Thursday and on Saturday I had to put another order in with all the record companies because we’d virtually sold half of our stock. There were queues on the motorway. You couldn’t get a park. People were parking on the hard shoulders of the Porirua slip road to get to the shop. It was just madness.”

Gareth Farr, composer, visits the Upper Hutt franchise of Tower Music, March 1999 (L-R): Tina Henderson of Tower Music, student Julia Harrison and Farr. - Chris Wilson, Upper Hutt Leader

Occasionally they felt like victims of their own success. “One of the funniest things we did was Peter Andre at the store in the North City Plaza. It was a Tuesday afternoon. He did about three numbers and there were thousands there. There were people climbing up the palm trees. We had to smuggle him in the back way and onto the stage. We got a bill for $3500 worth of damages to the trees!”

On another occasion, it was Pink Floyd that caused the trouble. “Pink Floyd brought out a limited edition of Pulse: a double CD in a little box with an LED light pulsing on the end. We bought 3000 of them. At the back of the shop in Porirua we had a big storage area. These turned up and we unpacked all of these CDs, it was to be released the following day. Anyway, I got a call at 10 o’clock at night from security to say there’s a fire in the back of your storeroom, so I jumped in my car. It wasn’t a fire; it was three thousand lights blinking – flashing at the back of the store! Of course it wasn’t dark when we’d left them.”

Motorvatin': Tower Music car in its 1990s splendour. - Nikki Adams collection.

After seven successful years, Tower was bought by Sounds. It turned out to be good timing. “It was before Napster, piracy and all that stuff.” Could Clansey see it coming? “Vaguely. You have to, in any business, have an exit strategy. We loved every minute of it, but in the end we thought, will it be worth any more in 12 months’ time or two years’ time? I had a contract to keep working there for 12 months, but I lasted six. When you work for yourself you’ve got the motivation. It was sad in the end but it was the right thing to do.”

Parsons’ Books & Music

Located on the ground floor of the iconic modernist Massey House, Parsons was the most specialised and most elegant of Wellington’s music shops.

It was started as a bookshop by Roy Parsons, a Fabian socialist who had emigrated to New Zealand from Britain to escape the stifling class system. His shop had several addresses in the Lambton Quay area before it took up residence on the ground floor of Massey House when the building opened in 1957.

Parsons Books in 1958, showing the modernist interior designed by Ernst Plischke. - Parsons collection

Parsons worked closely on the design of the shop with the building’s architect, Austrian-born Ernst Plischke, who had arrived in Wellington with his innovative ideas in 1939, the same year as Parsons. Together they created a place that was modernistic, slightly stark yet exquisite. A staircase curved gracefully up to a mezzanine where a coffee bar heightened the air of European sophistication. The café also helped ensure a steady flow of traffic through the shop. People might not buy a book every day, but they would always come in for a coffee.

Igor Stravinsky, in Wellington in 1961 to conduct the NZBC Symphony Orchestra, dropped by. On his return to the United States he told a reporter: “I’ve just seen the most beautiful bookshop in the world.”

For a period in the 60s, Parsons, a classical music lover, ran a small LP rental service out of the store. But it was his son, Julian, who saw the opportunity to become Wellington’s most reliable and wide-ranging retailer of classical music. In the 1970s Julian, who along with his sister Beatrice worked in his father’s shop, had been a frequent customer at Colin Morris’s Terrace store, with its entire upstairs devoted to classical music. Other than the mail-order service of the World Record Club, quality classical records were hard to come by. But when Colin relocated to Lambton Quay in 1979 and cut back his classical section, Parsons decided to fill the gap. Ignoring Colin’s warnings that “you can’t make a living out of classical music”, he reasoned that there should be a natural crossover between book-buyers and classical listeners. Most importantly, it would enable him to keep buying classical records for himself.

Things started slowly, but the turning point came with the arrival of the compact disc. “In 1983 [record company] Philips did a tour of record shops round the country, showing off what CDs could do,” Parsons remembers. “And I had an immediate response, thinking, ‘this is the way’. They were convenient, had good sound, and people started to replace their LP collections.”

Within the first few years of selling classical CDs, sales grew rapidly, trebling in one year. Parsons kept adding shelves to house the shop’s fast-growing stock. First the discs spread to the back walls of the bookshop, then they began to creep over the walls of the coffee shop as well. A jazz section was added in a rear alcove. An entire wall was colonised by opera.

Parsons Books & Music, 2010s. - Booksellers NZ

While Parsons kept abreast of new classical releases, reading the monthly Gramophone magazine and reviews in the British press, he also took tips from regular customers and a knowledgeable staff.

At its peak the shop stocked 17,000 discs. Though the late 80s saw a downturn in book-buying, CD sales continued to climb. Eventually the shop was making more money from music than books.

Parsons Books & Music thrived until 2007, when a combination of the global financial crisis and the rise of digital downloading services such as iTunes contributed to a sudden and irreversible decline in disc sales. Parsons closed the shop in 2014, but he looks back on his days as a music retailer with nothing but joy.

Home, work, and other important places: Julian and Beatrice Parsons, 2014. - Radio New Zealand

“Even though Wellington wasn’t really big enough to have a classical music shop as big as we were, it was satisfying – for customers and for me,” he says.

“I was reading somewhere recently about the importance of third places. The idea that in our lives there is home and work and the other places that are important to you, like a particular coffee shop we like or a place we like to go for lunch. Places one is emotionally connected to, that are part of who you are. And I think Wellington is very good for that. When I closed down, I got this tremendous feedback from people saying ‘We’re going to miss this. This has been an important part of my life.”

Solid Air Records

One of the city’s smallest but most fondly remembered stores, Solid Air Records occupied sites in Vivian Street and Ghuznee Street respectively, between the mid-80s and mid-90s.

In the early 80s John Pilley lived in London, where he would bargain hunt for records in the secondhand markets. In 1982, after he had moved back to Wellington, there was a record fair advertised at the Overseas Terminal, so he and a friend booked a stall.

“We thought ‘Record fair! Great! We’ll go through our collections, pick a few things out, sell a few things and make enough money to buy other interesting stuff from the people at the market.’ We had some quite rare out-of-print stuff, obscure artists we had tracked down and bought in the UK when we lived there. We took our stuff down and we had the only interesting records there. So there was a bit of a disappointment but we sold virtually everything we had.”

Encouraged by his sales success, he opened a weekend stall at the Wakefield Street Market. He called it Solid Air, after a favourite John Martyn album. He started with his own collection and friends’ discards. Soon customers would be bringing in albums they had tired of, and he built up stock. When his weekday job on the City Council’s summer entertainment programme ended, he found a hole-in-the-wall in Vivian Street with manageable overheads, built his own fittings, and Solid Air Records became a full-time business.

John Pilley, Solid Air Records, Vivian St, 1988. - photo by Chris Bourke

Though the bulk of his stock was secondhand vinyl, John began selling selected new titles. A South Islander by birth, he already knew Roger Shepherd and Hamish Kilgour of the Flying Nun label and, in the label’s early days, Solid Air was known as the Wellington shop where one could reliably find their releases. Around the same time, New Zealand was seeing tours by Australian indie bands such as Hoodoo Gurus and Harem Scarem. On a trip to Melbourne, John established a relationship with their label, Au Go Go, and stocked the popular Aussie indie at a time when no one else was. When Flying Nun started its Flying In import wing, he sold new vinyl by the likes of Sonic Youth and Primal Scream that was hard to find elsewhere.

In the early 90s he took a punt on moving to a larger store in Ghuznee Street. Though CD sales were growing, he resisted the new format for a long time (he did sell cassettes). Eventually he began stocking some new local CDs, and ultimately secondhand ones as well, though vinyl remained his medium of choice.

Selling records, he says, made him feel like part of a musical community. Writhe studio was across the road from the shop. One day Peter Gutteridge came in, “bouncing off the walls, looking for something he had recorded because he couldn’t remember how to play it.” John was happy to help.

“Even though I was a few years older than most of the customers I developed really good relationships with them. The key thing was having people trust the judgement of the person behind the counter. When [local indie] Pagan released Paul Kelly’s Post album I was selling it with a money-back guarantee. None of them came back.”

He formed close relationships with local bands. In the late 80s he became a regular at the Cricketers Arms where the newly formed Warratahs were holding their long and popular residency. When Barry Saunders told him one night that they had recorded an album, John directed him to Pagan, the label of his old Dunedin friend Trevor Reekie. Trevor liked what he heard, released the album, and The Only Game In Town became a top local seller.

The Only Game in Town: in 1987 John Pilley recommended The Warratahs to his friend, Pagan’s Trevor Reekie.

In London, John had seen bands hawking their wares at gigs, though this was not yet common practice in New Zealand. “I was ordering The Only Game In Town by the caseload, selling them in the shop,” John remembers. “On a Friday night I’d take a huge stack down to the pub, get there just before the band arrived, lay them out on the table and give each member a black pen. They would go along in factory sequence and sign the backs of the albums. Then when the punters arrived, I’d go around table to table and sell autographed copies of the album. We did well with that.”

But by the mid-90s vinyl sales had slowed down and John still hadn’t developed much affection for the compact disc. What’s more, Indies like Flying Nun, who he had once bought from directly, were now working through majors who had little interest in dealing with smaller retailers like Solid Air. So, in 1996 he shut up shop, going back into event management before spending decade as music production manager at Radio New Zealand. He now runs his own voice recording studio, Solid Air Productions, but he retains fond memories of the musical community that Solid Air Records made him a part of.

He remembers going to a gig one night by local speed-punks Flesh D-Vice which, with their motley audience of metal-heads and boot-boys “could be a bit daunting for someone who is a bit older and doesn’t have any tats”. He was lurking discreetly at the bar when guitarist Eugene Pope pointed him out from the stage. “That guy over there…” he shouted. John was checking the exits in apprehension of what might be coming next when Pope concluded: “He’s got the best fucking record shop in town!”

Allan’s Compact Discs

Allan’s Compact Discs opened just before Christmas 1989 with an obvious point of difference: it dealt exclusively in CDs. With all the industry buzz about the superiority of the new format, the shop instantly had a modern, specialised feel. It helped that the shop’s founder Allan McFarlane was a dedicated fan of classical and jazz, the two genres that switched almost overnight to the new medium.

Initially Allan was assisted in the store by film and music aficionado Andrew Armitage. When Andrew left to concentrate on his Aro Street Video shop, Allan was joined by the knowledgeable Brent Gleave, who had previously managed stores for Chelsea and HMV. “Allan and I pretty much had completely opposite taste in music,” recalls Brent, “so between us we covered a pretty broad spectrum.”

Allan’s shunned the Top 20, almost on principle. - Yellow Pages listing, 1990.

In spite of its small premises, the CD format meant the new independent store was able to accommodate a wide variety of titles. The store quickly became a magnet for anyone whose tastes veered at all from the mainstream, whether it was towards classical, jazz, rock or electronica.

“The left-field stuff – I guess a lot of it came from me,” Brent concedes. “But I have to give Allan massive credit here, he let me go with whatever titles I thought were worthwhile whether we sold two copies or 200, and that created an interesting catalogue for such a small store. I’d simply read about an interesting title and chase it down and have a listen. We had to work pretty blind, there was no Spotify and such like – so when we found something new which we could work it was pretty exciting. We worked hard, but the workload was fair and we both enjoyed each other’s company and respective tastes. And we did some pretty serious business in that wee store.”

They shunned the Top 20, almost as a matter of principle. “It meant nothing to us. Occasionally the odd commercial release would fall into the Allan’s ‘vibe’ and because we liked it we would run with it. The most common occurrence would be a relatively obscure or new band we would find and have success with, would then make it onto the chart at a later date, or with their next album.”

With their boutique approach and somewhat concealed location on the second level of the Willis St AA Centre, it might seem surprising that Allan’s thrived as it did. But throughout the 90s Wellington evidently had enough discerning music fans to keep the store pumping. Eventually they moved just around the corner to a larger premises, which allowed them to expand their catalogue and scope. They added an office and a processing room. Their monthly newsletter, with capsule reviews of new albums, became a very effective part of their marketing.

“Allan’s had a lot of regular customers”, says Brent. “In the early years they were mostly professional and mostly male. As the store made a name for itself this expanded to include a number of businesses, students, actors, arty types, and the mix between male and female evened out more. I guess to our credit most of those early regulars stayed with us.”

But by the early 2000s the times were changing, and Allan’s was bought by online music retailer Smoke CDs as their “bricks and mortar” store. While Brent stayed on and attempted to maintain the unique music selection that had distinguished the shop for more than a decade, Smoke’s focus was on selling large quantities of Top 20 albums and the character of the store was irrevocably changed. Before long Brent had left; the store closed not long after.

Now based in Australia, he looks back fondly on his days working with McFarlane. “We both put a lot of time and effort into researching and sourcing the music. It was a lot of fun and very satisfying and ultimately what made the store what it was. In all honesty, I don't think either of us would have wanted to do it any other way.”

Real Groovy

Real Groovy spent 12 years on Cuba St, Wellington, from 1999. Certain styles of music sold better in the capital.

Real Groovy Records landed in Wellington in early 1999 like an invasion from Planet Auckland. Over the previous 20 years, the Auckland shop’s founder Chris Hart (with a succession of partners) had built a reputation for grand gestures, whether it was commissioning a $20,000 neon sign from artist Paul Hartigan, launching his own free monthly magazine (Real Groove), or opening the half-acre wide, two-storey Queen Street store.

Situated at the corner of Cuba and Abel Smith Streets, the Wellington premises was modest compared to Queen Street, still it was easily the biggest record store Wellington had ever seen, and with its garish green signage one could hardly miss it. Other Wellington record retailers – particularly those in the secondhand market – were understandably put out, but with dedicated local staff it quickly established itself as a destination for music lovers.

During its 12-year stint in Wellington, it focused predominantly on CDs, both new and secondhand, but always stocked a large selection of secondhand records. Paul Huggins began working at the shop just before it opened and remembers cleaning 4000 LPs, by hand. The shop also sold DVDs, books, T-shirts, headphones and other music-related ephemera, as well as having a box office where tickets for live shows could be bought. The shop replicated the pricing system Hart had perfected in Auckland, where records would get cheaper the longer they stayed in the shop, ensuring a constant turnover.

CD racks in Real Groovy, Cuba St: where Auckland went for house and techno, Wellington favoured drum ’n’ bass.

Within a short time, the shop was rocking. Initially stock was shipped down from Auckland and buying supervised from head office, but it gradually changed to reflect Wellington’s unique character. Certain styles of music such as reggae sold better in the capital. The dance culture was different too; where Auckland went for house and techno, Wellington favoured drum ’n’ bass. Local bands would play in-store shows and discs by the likes of Fat Freddy’s Drop, TrinityRoots and The Black Seeds flew out the door.

Expanding further, in 2006 Real Groovy bought the South Island Echo Records stores, and Huggins went south to manage its Christchurch shop. But in 2008, stretched to breaking point by some of the company’s Auckland-based projects, the company went into receivership. The Dunedin store was closed permanently; the Christchurch store was bought by Huggins and Wellington taken over by manager Mark Thomas. Neither of these shops were to last long. The Christchurch earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 sent Huggins back to Wellington, where he opened Rough Peel Music which continues to this day, while Thomas closed the Wellington Real Groovy store around the time of Huggins’ return and relocated to New Plymouth where he now runs The Vinyl Countdown. Both continue to employ many of the lessons they learned at Real Groovy.

--

Read: Wellington’s Early Record Stores

Read: Wellington’s Lost Record Stores – a personal introduction

Read: Wellington’s Lost Record Stores 2 – burbs and back alleys

Read: Silvio’s – the accidental record store

Read: Colin Morris

Read: Soul Mine

--

Thanks to Colin Morris, Dennis O’Brien, Nikki Adams, Christopher Read, and Kevin Kane

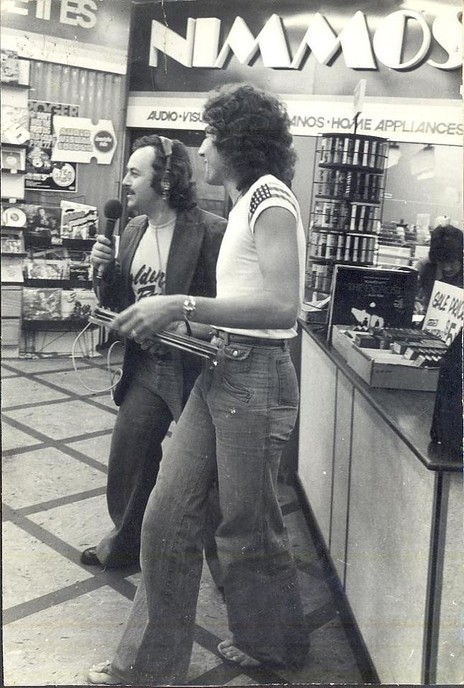

Nimmo's, corner of Willis and Bond streets, mid-1970s. An outside broadcast hosted by 2ZM deejays Mike Dee (left) and John Hood. Cassettes on sale, and The Exorcist soundtrack within easy reach. - Mike Dee collection