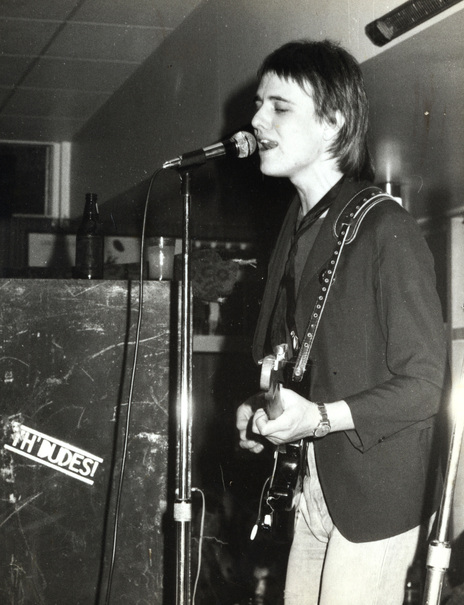

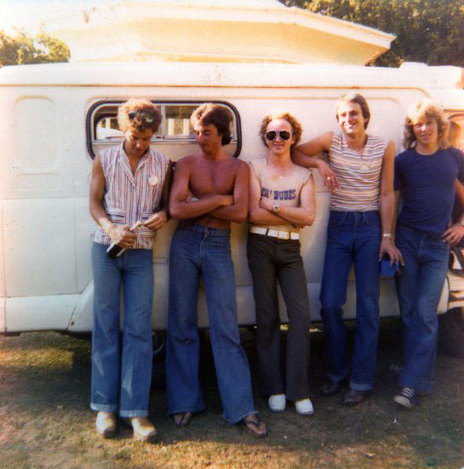

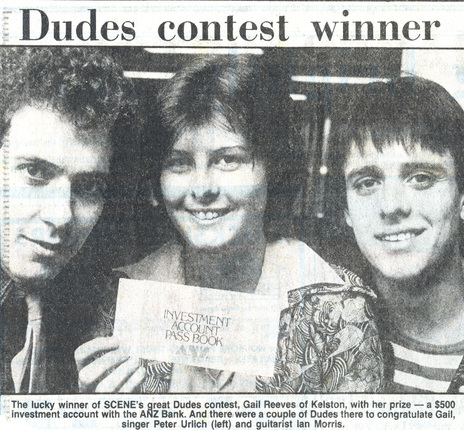

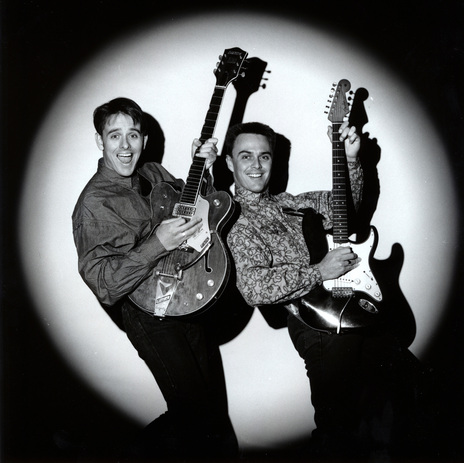

Soon after engineering the first Hello Sailor album, Morris quit his day job at Stebbing. Th’ Dudes – the band he formed with his school mates – were shaping up to be the next big thing.

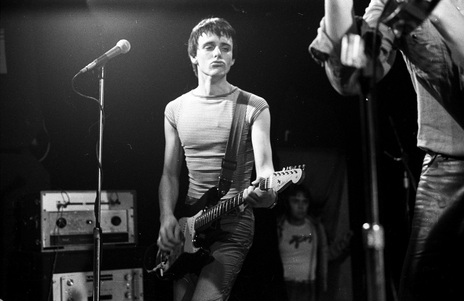

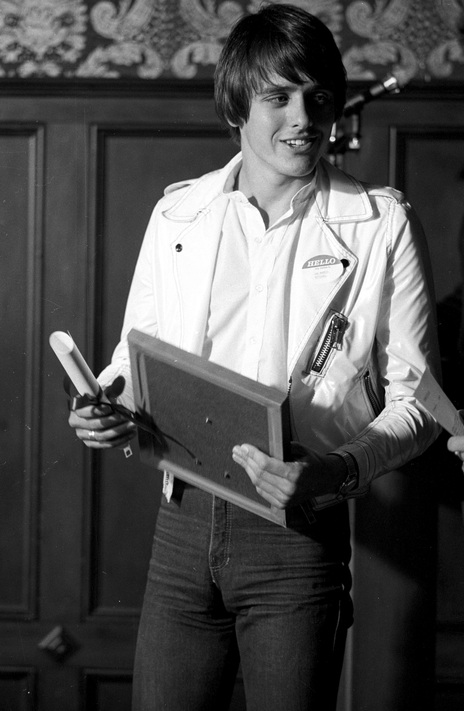

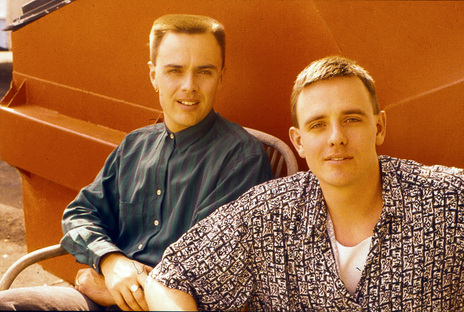

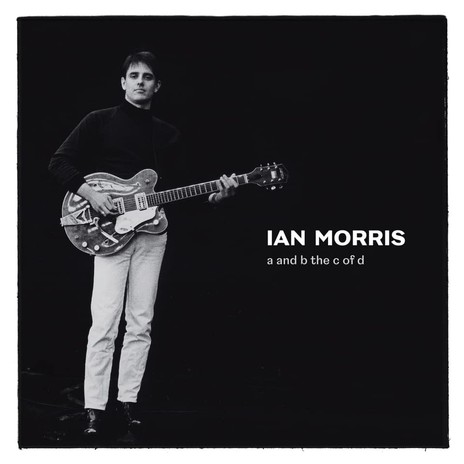

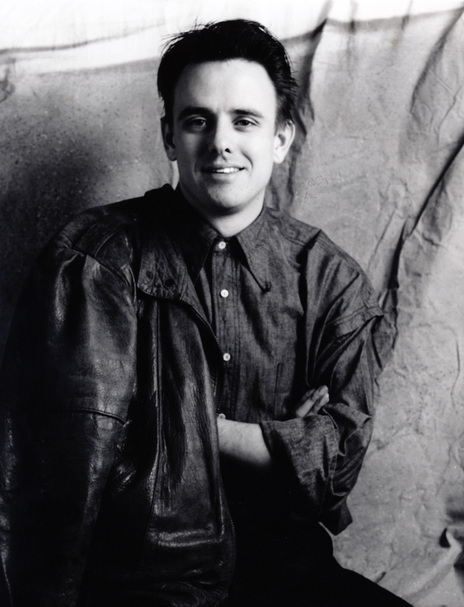

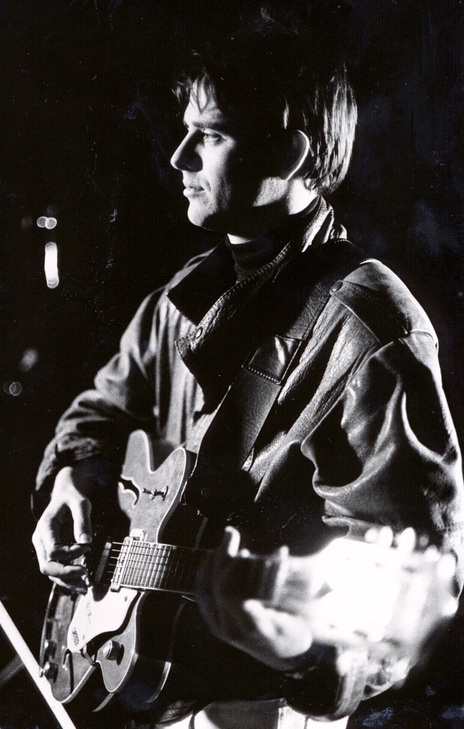

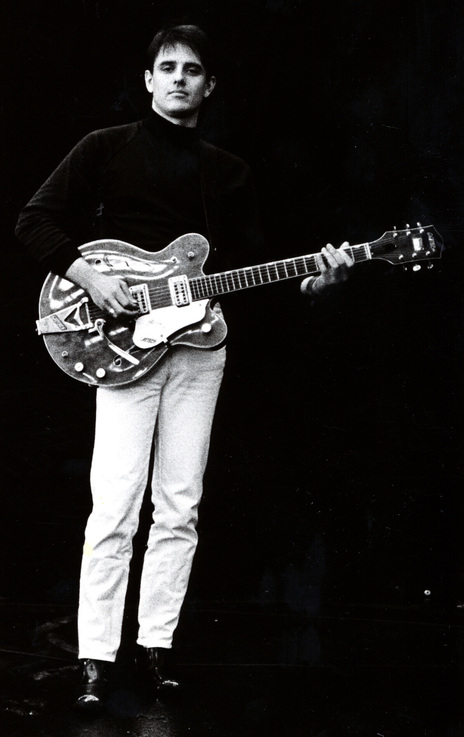

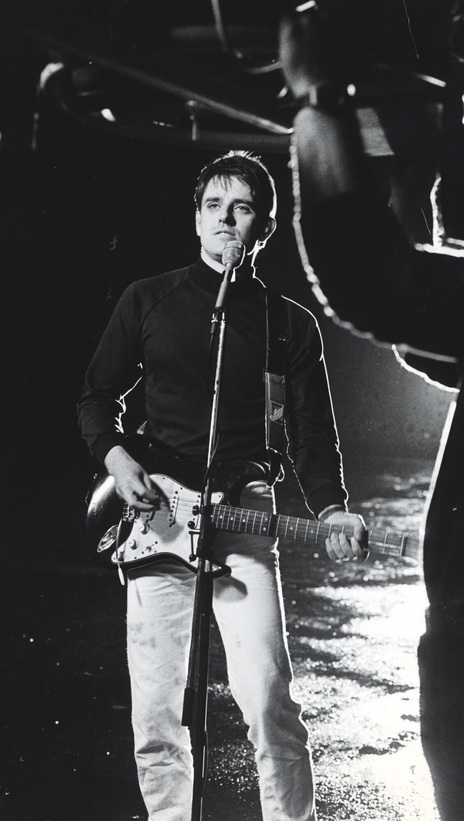

Morris experienced stardom with Th’ Dudes and under the guise of Tex Pistol.

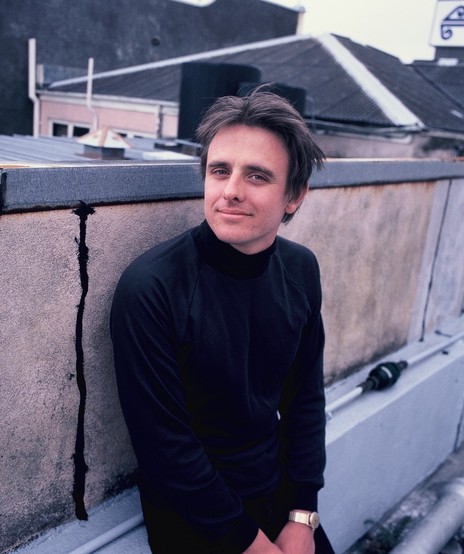

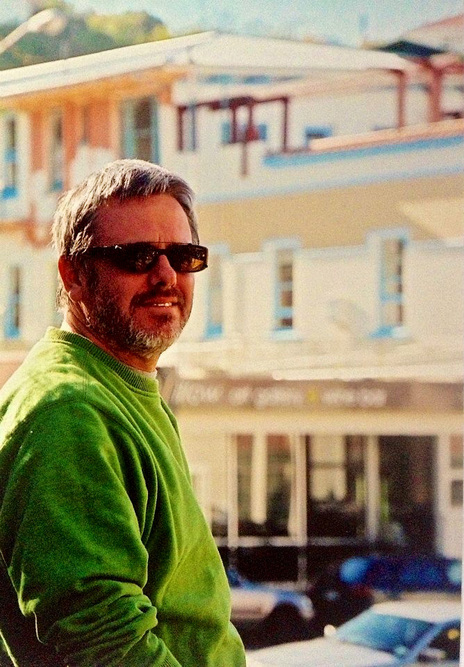

Morris experienced stardom as a member of Th’ Dudes and as a solo artist under the guise of Tex Pistol. But in a 35-year career in the New Zealand music industry, it was behind the scenes that he made his most significant impact. As a guitarist, songwriter, engineer and producer he was a master of all trades; he was an example of what happens when talent meets 10,000 hours of hard work, also known as serving an apprenticeship.

At high school, he teamed up with two classmates who shared his obsessions: Peter Urlich and Dave Dobbyn. Soon they would become the frontline of Th’ Dudes. Once out of school, Morris became a trainee engineer at Stebbing. Sessions with brass bands, choirs and symphonies were all part of a day’s work, as well as making countless commercials. Working alongside jingle maestro Murray Grindlay taught him to work quickly and imaginatively, with a goal of capturing the maximum number of ears.

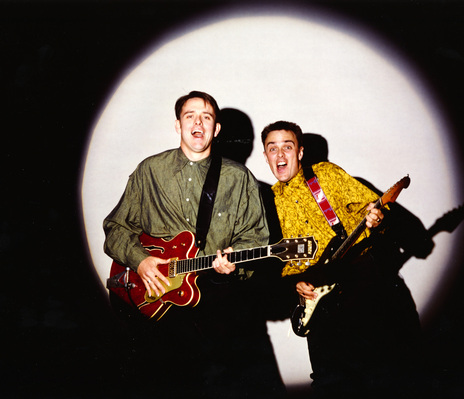

While at Stebbing he engineered Hello Sailor’s classic albums on Key, Th’ Dudes’ own albums, plus those by Golden Harvest, Patsy Riggir, Toni Williams and many others. After hours, he was on stage as rhythm guitarist in Th’ Dudes, playing proven, dance-friendly hits at school balls, weddings and in pubs.

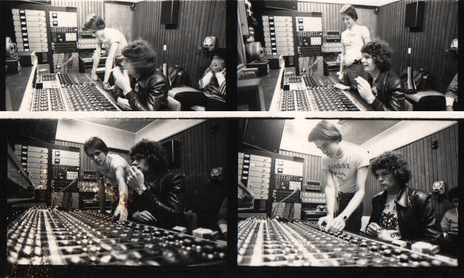

As a boy he spent hours building model aircraft, and his approach to listening to music was similar – he deconstructed a song then recreated it. Morris quickly absorbed an array of music styles, and decrypted the secrets of a great pop song: memorable riffs, hooks, choruses, and lyrics, made coherent with structure and inventive sounds. He saw the studio as a palette of sonic colours with endless creative possibilities. But beyond his flair with knobs, sliders and VU meters, he learnt that it above all else, in the studio what mattered was capturing a great performance.

The Beatles’ Revolver had just been released when Morris arrived in New Zealand in 1966. He was aged nine, and emigrated from the UK with his parents, an older sister and a younger brother. His sister Dorothy was five years older, so was a young teenager as Beatlemania began to take over Britain in 1963. “She was a Beatles freak,” he said in 2001. “So soon I’m six, singing ‘From Me To You’ with my brother Rikki, while playing my tennis racquet.”

Settled in the east Auckland suburb of Glendowie, the Morris family bought a tape recorder to send messages home to relatives in Britain. Ian and Rikki were recruited to play their latest piano pieces, or sing duets; Christmas carols and cloying duets by Nina and Frederick evolved into renditions of Simon and Garfunkel that took advantage of the boys’ harmonies. Single-channel television meant the whole country simultaneously watched variety shows such as Morecombe and Wise or The Black and White Minstrel Show, in which The Beatles or Tom Jones might appear.

His mother Julie was musical and broad-minded; she could explain the qualities that made Sinatra or Cole Porter special, yet she didn’t dismiss 1960s pop. After strumming a toy instrument emblazoned with cartoon Beatles, he was given a real guitar for Christmas in 1966. Morris soon gave up piano lessons, and concentrated on pop music. With Rikki he appeared at Scout “gang shows” (variety concerts), and in 1968 the duo entered the 1ZB Talent Quest at Redwood Park, which was broadcast live. They won with a version of the Seekers’ ‘Walk With Me’. When the pirate station Radio Hauraki began broadcasting in Auckland, pop radio improved dramatically.

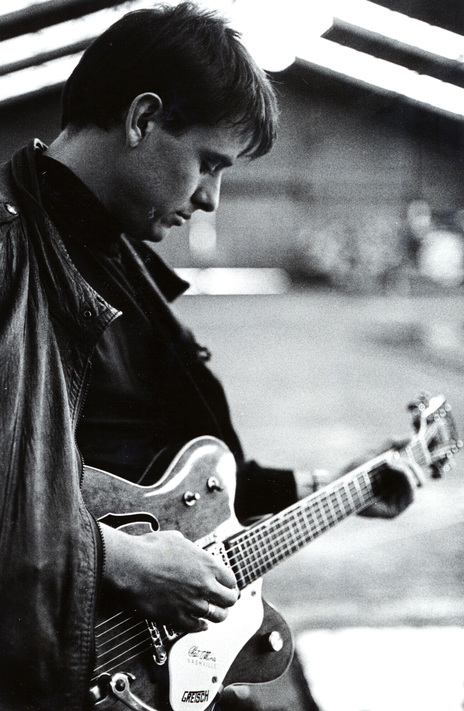

He switched his family gramophone to 16rpm to learn Keith Richards’ solos at half-speed.

In about 1972, Morris acquired a cassette player, so he was able to link it to the family reel-to-reel and record overdubs. His sister got married, and her husband had “every Beatles record, every Jimi Hendrix record, every Stones record,” he said. As a budding teenage electric guitarist, he switched his family gramophone to run at 16rpm so that he could learn Keith Richards’ solos at half-speed. “I used to go into the bedroom and re-record these things with a guitar, dubbing from cassette to tape recorder and back again, doing over-dubs to create these Beatles songs.

“I just loved the three-minute pop song. I became aware of what goes into making a record, what makes a record great. It’s not just a song, but a record. That’s what grabbed me – the aural landscape of a record – and the emotion you can convey in a sound, rather than just a lyric and melody.” On Radio Hauraki, the syndicated US show American Top 40 became essential listening – the wide variety of music played on the show became the key to his diverse tastes, and he always remembered host Casey Kasem’s aspirational slogan: “Keep your feet on the ground and keep reaching for the stars.”

Music also had a prominent presence at his local Catholic high school, Sacred Heart College. It was where he met Dobbyn and Urlich who, with a generation of students including the Chunn and Finn brothers, were deeply influenced by two teachers, Ivan and Quentin Gannaway. After hymns in the school assembly hall, the Gannaways would lead the students singing pop songs such as ‘Strawberry Fields’ and ‘Ob La Di, Ob La Da’. Of the trio, only Urlich was interested in playing sport; Morris and Dobbyn felt like outsiders and shared their love of pop and Goons-style humour. Dobbyn was too shy to perform at school, so Urlich and Morris aspired to be “one of the star duos: Mick and Keith, Bowie and Ronson, Townshend and Daltry. We just loved the rock and roll dream.”

The founding of Th’ Dudes and the group’s subsequent flamboyant career have been covered elsewhere at AudioCulture. Morris’s memoir How Th’ Dudes Got Started evocatively describes the mid-70s period when the band took shape: hours rehearsing using Jansen guitars and homemade amps, while dreaming of Fender Twin Reverbs and Telecasters, and recording sessions at Abbey Road and the Manor. “Just for now though, we’d settle for the sniff of a chance to get up and play at the Glendowie Tennis Club annual dance …”

For weeks they worked their way through a jukebox of dance floor fillers by the likes of Chuck Berry, The Rolling Stones, The James Gang, The Commodores and Little Feat. Plus, the “perfect pop” of Mott the Hoople, Bowie, T Rex, and “wildly ambitious covers of 10cc and Steely Dan, trying to re-create on a Saturday afternoon with two guitars what Godley and Creme and Becker and Fagen had taken a year and several million dollars to achieve.”

By learning from the masters, Th’ Dudes found their own voice. Morris regarded their 1979 debut single, ‘Be Mine Tonight’ b/w ‘That Look In Your Eyes’, as, “The first songs we wrote that were really our songs ... not Godley and Creme, or Jagger and Richards.”

The follow-up, ‘Right First Time’ was credited to Dobbyn and Morris, but mostly written by the latter as a deliberate attempt at a radio hit. “It was just as hard then getting your song played on radio as it is now,” Morris said in 2001. “So I was looking for something ‘dumb’ enough that radio people could say, ‘Yes I can play that, I sort of recognise those chords …’”

After achieving most of its goals – hit singles, two accomplished albums, many national tours, rock-star behaviour – the band broke up in early 1980. The catalyst was a dispiriting tour of Australia as support act for the Members. Morris could not face the years of playing leagues clubs and touring the backblocks of the country required to possibly reach the success they had enjoyed in New Zealand.

For Morris the post-Dudes period was difficult, and occasionally dissolute.

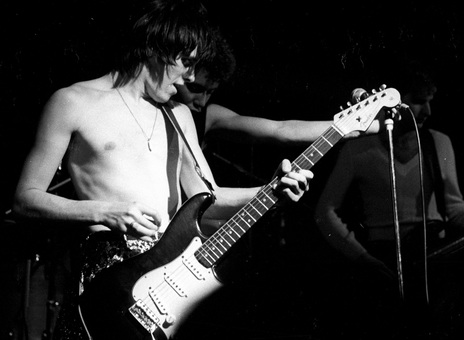

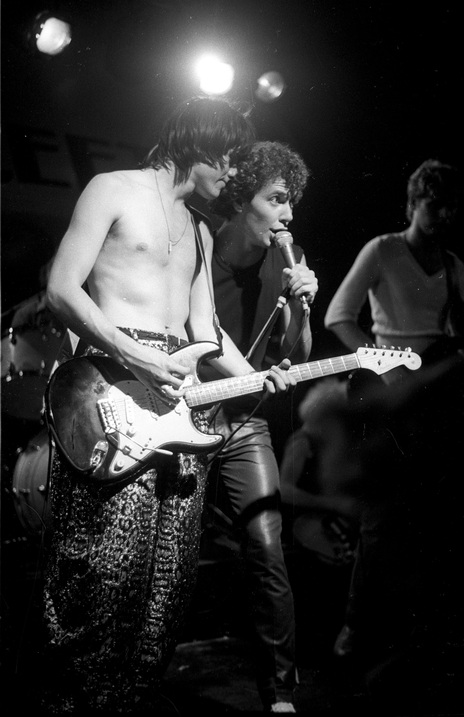

At Th’ Dudes final gig, in May 1980 at the Auckland rock club Mainstreet, Morris performed on stage naked, his “todger” covered by his Fender Stratocaster. The breakup had been his suggestion, but for Morris the comedown of the post-Dudes period was difficult, and occasionally dissolute. He briefly joined Dave McArtney’s Pink Flamingos but lacked the focus required.

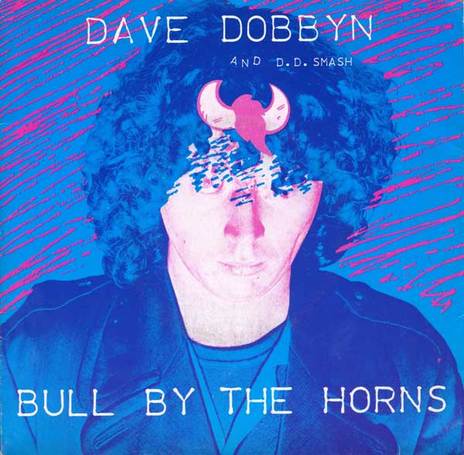

He returned to the studio, booked some time at Stebbing for Dave Dobbyn, and late at night worked on original songs by Dobbyn towards a planned debut album. The results were Dobbyn’s first two solo singles, ‘Lipstick Power’ and ‘Bull By The Horns’; a B-side was ‘Behind The Painted Smile’, an early hit by the Isley Brothers. To emulate the heavy handclaps of Motown, the pair set up a microphone and stomped on wooden boards. As a freelance engineer and producer, Morris found his purpose again.

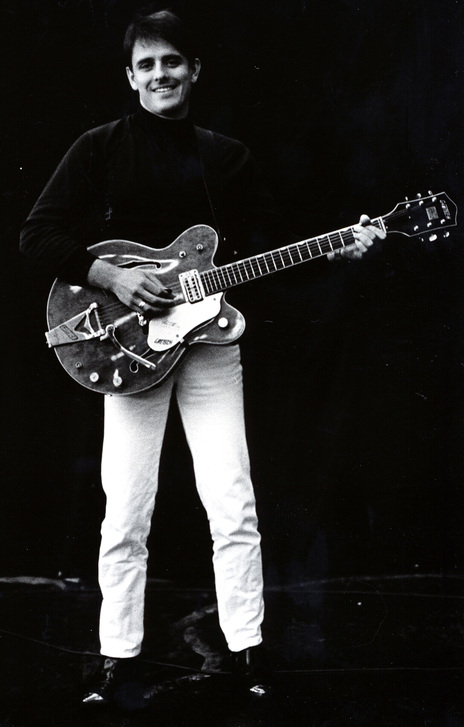

Morris had just left school when he first joined Stebbing in 1975. “I didn’t want to do anything but play the guitar,” he said in 2001. “Then I saw an ad in the Herald – ‘Junior Engineer Wanted’. I went along and met Eldred, and played my trump card. I said, ‘I play in a band, too’, thinking this would really swing it. Eldred said, ‘One day, you’re going to choose between the band and this job,’ and he was right.”

At Stebbing, Morris began at the bottom, “not quite making the tea”, but everything else. He ran off thousands of tapes, and used a cutting machine to make 7-inch 45rpm lacquer discs of jingles for radio stations. “It was a great learning experience. Apart from going to the BBC or Abbey Road, I can’t think of any better training for an engineer. Because everything was done exactly by the book, and once you know the rules in the book then you can break them – and you know how to creatively break them.” When he began working freelance at other studios, he was shocked to see how poorly they maintained their equipment. At Stebbing, every new piece of machinery was taken apart so they could know how it all worked, then put back together, sometimes with improvements.

After nine months of dubbing tapes, Morris was promoted when an engineer left. “Suddenly I was recording voiceovers for commercials, with high-pressure advertising people breathing down my neck. So I had to learn very quickly what I was doing.” Soon afterwards, he was engineering albums at the studio, and he found a natural partner and mentor when Rob Aickin was hired as an in-house producer. A former member of the 1960s Auckland pop band the Clevedonaires, in the UK he had done some studio work at Island Records with Muff Winwood. On his return Aickin approached Eldred Stebbing and convinced him that he could produce albums that would sell.

Morris was impressed by Aickin’s “commercial ear” and his willingness to experiment in the studio, using every gadget in the toolbox to “get a good blend of sound”. Special moments included the Golden Harvest album (“pure pop”), Lea Maalfrid’s ‘Lavender Mountain’ and of course the carefully crafted albums by Hello Sailor and Th’ Dudes.

Morris had suggested to Eldred Stebbing that he sign Hello Sailor, and always remembered the day the band arrived for an audition. They set up their gear in the studio and ran straight through their songs like a live gig, with the added tension that they needed to impress (the demo tape was later stolen from his flat). He recalled that on the Sailor debut album, he and Aickin “tried to mould the songs into singles: ‘Gutter Black’, ‘Blue Lady’. We double-tracked the guitars, the saxes, cut things out of the middle. But they weren’t three-minute singles. They’re classic New Zealand songs, but not classic pop songs like ‘Tiger Feet’ by Mud [1974], which is. ‘Blue Lady’ isn’t.”

In the early 1980s, Morris became a producer at large, working in Auckland and Wellington.

Like George Martin, who perennially has to relate secrets from Abbey Road, Morris was always asked about the ‘Gutter Black’ snare sound. “I’d just heard Low by David Bowie, where the snare drum is put through a harmoniser on every track. We didn’t have a harmoniser but we had a mechanical flanger. So I put a microphone down the end of this huge studio, played the snare through some big speakers at the other end, then put it through the flanger. It’s just a big drum sound. It was an experimental time.” Similarly, the two Dudes albums – which Morris lovingly over-dubbed, engineered and mixed – show how the band revelled in their opportunity to use the studio as an instrument and emulate their heroes.

In the early 1980s, Morris became a producer at large, working in Auckland’s Mandrill and Harlequin studios, and Marmalade in Wellington. He produced and engineered demos, singles and “mini-albums” (12-inch EPs were in vogue) for acts such as Graham Brazier, Naked Spots Dance, The Hulamen, Andrew Clouston, Circus Block Four, Lip Service, Tin Syndrome, Daggy and the Dickheads, The Furys, Shadowfax, and The Gurlz (the latter session introduced him to Kim Willoughby, who he married in 1995).

He produced two prominent albums in this 1981-1982 period: The Screaming Meemees’ If This is Paradise I’ll Take the Bag and DD Smash’s Cool Bananas. New Zealand’s hottest pop act in 1981, the Meemees went in to record a single, but were unprepared, so Morris sent them home to rehearse. They came back with “very simple songs, and it was a great exercise to take these very simple songs and throw these hooks into them.” Morris looked back at his production in 1988 and described it as “very porridgy … not only had I put the kitchen sink in there, I’d put the blender and the electric knife in as well.” He saw Paradise as a transitional album for the Meemees that led to their self-produced, and acclaimed, single ‘Stars in My Eyes’. But time has been kind to the album; while the inadequacies of Harlequin Studio are apparent, and the sounds are unmistakeably from the early 80s, the band’s mix of power-pop, electro, dub and funk styles exemplified cutting-edge post-punk. Label manager Simon Grigg recalled it was Morris’s “whiskey-soaked production which helped make the record what it was – that and the ongoing parties that were part of the recording sessions.”

Cool Bananas captured the first phase of DD Smash when it was the biggest pub-rock attraction in the country. It opens at full speed, the first chord and vocal of ‘The Devil You Know’ arriving simultaneously, with no introduction – emulating the early Beatles. The experience and empathy shared by band and producer resulted in a self-confident album that was the first by a local act to enter the charts at No.1. Dobbyn’s chugalug pub-rock songs filled dance floors, and were captured well on disc, where they were also leavened by the occasional subtle moment that hinted at the more sophisticated music that was to follow. This was mainstream rock for the masses, who responded with enthusiasm.

The many skills of a record producer include being an amateur psychologist.

The many skills of a record producer include being an amateur psychologist, to bring the best performance out of an artist who may be intimidated by the task, or whose energy may be fading. Morris learnt how to nurture the musicians, encouraging them to a better take, but knowing when to stop. It may have just been saying, “Nearly …” through many vocal takes, or daft phrases that relaxed the person at the microphone – “One more time for Ringo” – or, to a saxophonist struggling with a solo, “Let’s try that again, with a sharper crease in the trousers.”

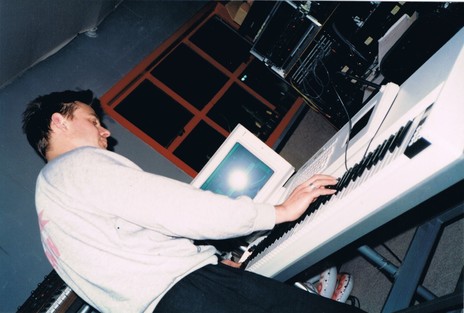

In January 1983 his production work was interrupted when DD Smash’s bass-player Lisle Kinney was injured in a car accident while the band was on a beach tour. Morris stepped in to play bass, just as the band was making a foray into Australia. The dreaded long car journeys to backblock bars, playing to disinterested Ockers had little appeal so within a year he was back. An early adopter of computers, he wrote and recorded a song ‘Boot Up (Let X = Y)’, inspired by the Basic language needed to code the technology used. Released as a 12-inch single by Hit Singles using his nickname Jag Moritz, it was heard by few, but it laid the template for his next step as a solo artist.

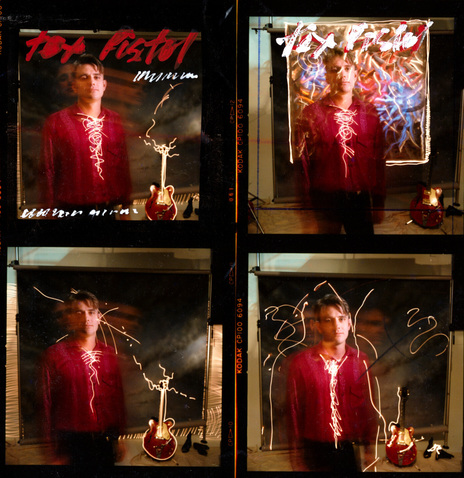

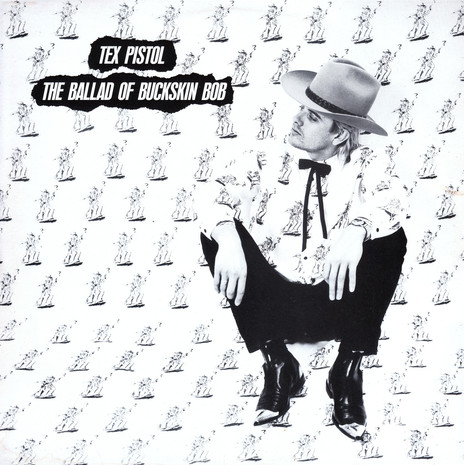

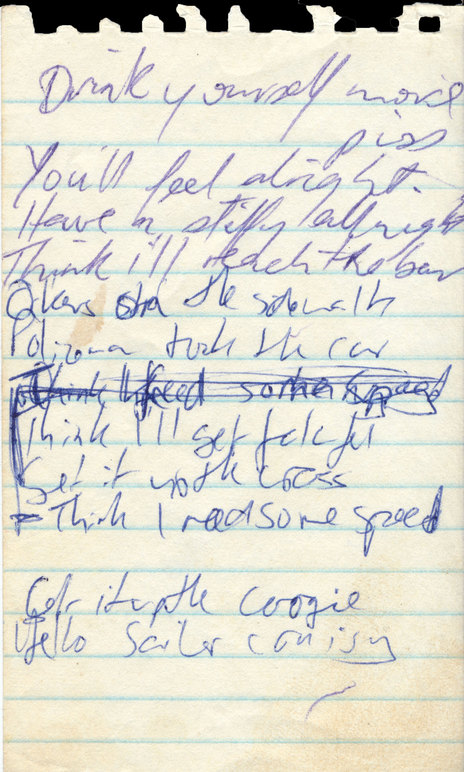

In early 1984 Morris took a temporary job engineering at Marmalade Studio in Wellington. He would remain in the capital for 10 years. The studio was often a refuge for Morris. He enjoyed his own company, pottering away doggedly experimenting with sounds and machinery. Late at night in Marmalade he began to work on a song written by his friend Lez White, bass player from Th’ Dudes. A parody of cowboy pop culture, ‘The Ballad of Buckskin Bob’ was part of Daggy and the Dickheads’ set, when White was a member (and with whom Morris often guested on guitar).

Morris saw the production and arrangement possibilities of the witty, hook-filled song, and used it to experiment with a new piece of equipment. The Emulator was a computer sampler which could copy sounds that could then be played back as musical notes on a keyboard. Its samples were limited to just 30 seconds, which could be joined as repetitive loops – so it was time-consuming to use but widely expanded the instrumental possibilities of a one-man band. (A violin could be sampled, for example, then played on the keyboard.)

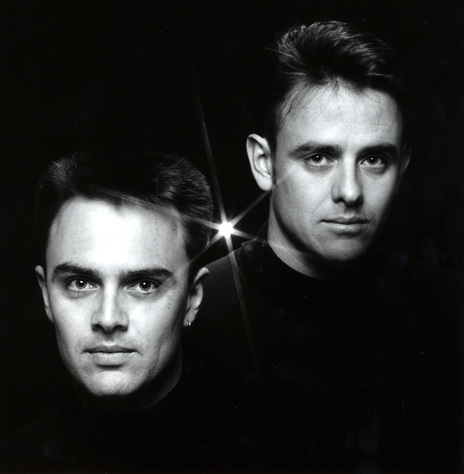

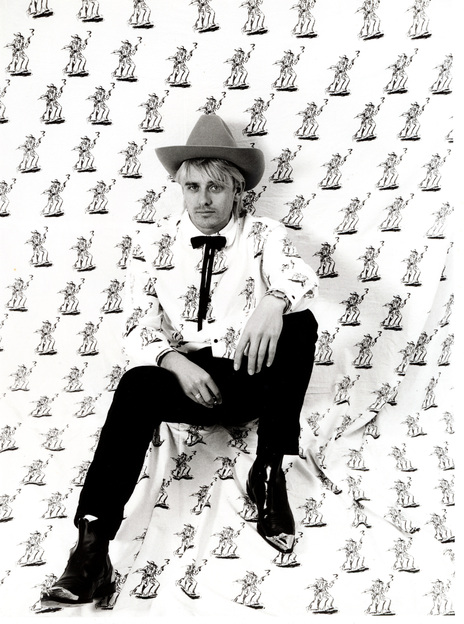

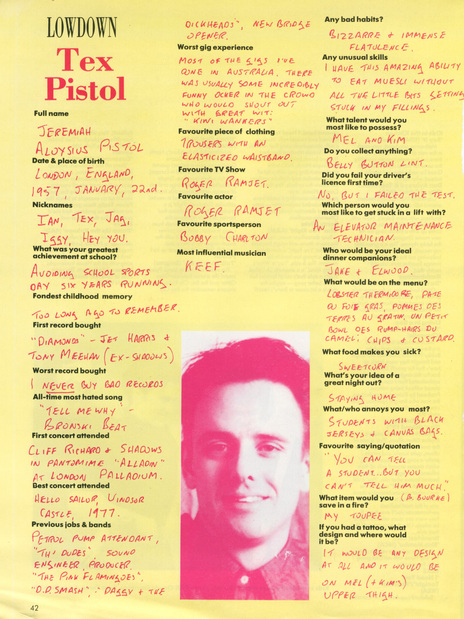

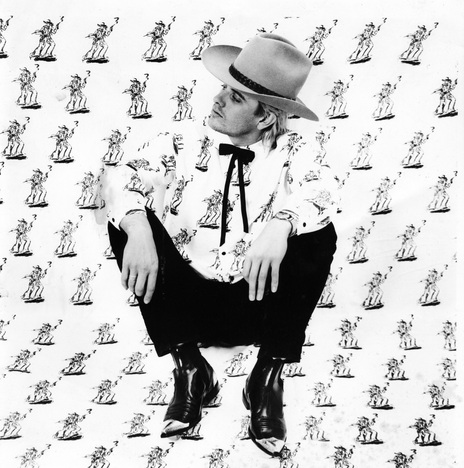

This pioneering, monophonic 8-bit floppy disc sampler enabled Morris to record almost every instrument in an epic arrangement of ‘Buckskin Bob’ and another Dickheads’ song, ‘Winter’. The sonic effects were panoramic, dramatic and humorous, with many musical references; think Sergio Leone meets Lee Hazlewood. Morris was reluctant to release the recordings, but was persuaded to put them out using a pseudonym. “Ian Morris just didn’t sound poppy enough,” he said, and an alias suited his take-it-or-leave-it approach to fame. “Tex Pistol” was appropriate to the songs, and the tongue-in-cheek spirit with which they were recorded.

Released in 1986 by Pagan, ‘Buckskin Bob’ received almost no airplay – very few New Zealand songs did at the time – but at the annual music awards, Tex Pistol received the awards for most promising male vocalist and best engineer. By the time he recorded a follow-up, Morris was a partner in Soundtrax, a Wellington music production studio that mostly wrote, arranged and recorded jingles. Soundtrax had upgraded its Emulator to the more sophisticated Fairlight, which could sample two minutes of music and had 16 polyphonic voices.

Soundtrax co-founder Jim Hall suggested that a suitable follow-up to ‘Buckskin Bob’ would be ‘The Game of Love’, a 1965 hit by Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders. Morris could immediately see the possibilities, and gave it a sparse arrangement – he had learnt that less was often more – with a slinky rhythm nailed down by another innovative snare sound. Supported by a stylish, monochromatic video by Paul Middleditch it became a No.1 hit in the New Zealand charts. Its reign at the top was brief – one week – as copies of the single ran out the day it reached No.1, but it received extensive radio airplay.

The Tex Pistol caper suited Morris’s attitude to the music business: he loved the music but not the business.

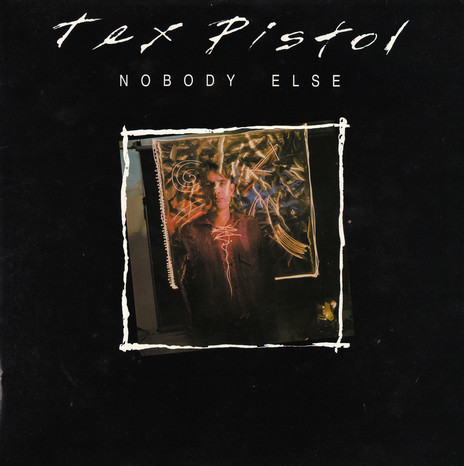

The follow-up came in 1988: ‘Nobody Else’ was a big, romantic ballad written by Rikki Morris, Ian’s younger brother, who also sang lead vocal (and over-dubbed many other vocals, in a variety of styles). At the suggestion of Pagan’s Trevor Reekie, it was released as Tex Pistol and Rikki Morris – which suited the limelight- avoiding producer just fine. The mainstream appeal of ‘Nobody Else’ was confirmed when it also went to No.1.

The Tex Pistol caper suited Morris’s attitude to the music business: he loved the music, and making hit records was part of the fun, but he could do without the business. It gave him a chance to experiment in the studio, and share the results with an audience, without it needing to be a career move. In the late 1980s, advertising music was booming, and Soundtrax was in demand.

Inevitably, Pagan wanted a Tex Pistol album, and Morris spent months after work remaining in the studio, tinkering on songs. Released in late 1988, Nobody Else was a light-hearted album that displayed the eclecticism of Morris’s craft. It mixed cover versions updated for the 1980s with Morris originals that showed his love of country music; a sincere country fan, his own efforts were always delivered with humour. The dominant personal statement of Nobody Else is mateship. Besides Rikki’s contribution, there was a cover of ‘Hands Of My Heart’ written by The Warratahs’ Barry Saunders (done Steve Earle-style); ‘Sitting In The Rain’ was a tribute to his former mentor, Murray Grindlay, who sang The Underdogs’ version; ‘Buckskin Bob’ and ‘Winter’ came from the Dickheads, whose singer Mark Kennedy contributed a Bing Crosby-style vocal to ‘My Old Friend’. In 1989, ‘Come Back Louise’ – another song written and sung by Rikki – was released as a single, to little interest. “By this time the tall poppy thing was clobbering us big time,” recalled Reekie.

In the 1990s Morris put his Tex Pistol alter ego to rest and concentrated on advertising music, with the occasional record production for others. In 1991 he produced ‘What’s The Time Mr Wolf?’ for Southside of Bombay, which went virtually unnoticed until its inclusion on the soundtrack of Once Were Warriors took it to No.1 in 1994. For The Warratahs he produced Big Sky and Wild Card, the last Warratahs albums to feature Wayne Mason. They showed how the technological experiments of the 1980s had given way to a natural, organic sound (especially on Mason’s ‘Tightrope’, and the instrumental ‘Akautangi Way’). Also in the early 1990s, Morris played twanging Carl Perkins-style guitar in the rockabilly group Big Fiddle, named after the double-bass of Nick Bollinger but spotlighting three harmonising vocalists: Callie Blood, Jackie Clarke and Janet Roddick.

In 1994, after the birth of twin daughters with Kim Willoughby, Morris moved with his family back to Auckland and continued production work. The highest profile project came in 1998, when he produced Dave Dobbyn’s Hopetown. Their relationship hadn’t altered since Th’ Dudes days: Dobbyn delivered many musical ideas, which Morris sifted through and helped shape into songs. ‘Just Add Water’ was the hit single, but the album was once again an array of their favourite genres, from gospel-rock to Bacharach-style ballads. Song craft met studio craft on his production of Greg Johnson’s Sea Breeze Motel (2000), which revealed Morris’s maturing skills at arrangement, acoustic and orchestral instruments, natural sounds and space; Johnson responded with an exceptional vocal performance.

Morris and his family moved to Napier in 2005, to be close his ageing father. The lifestyle also appealed, as did removing himself from mind-numbing advertising work. (For years, account directors with musical aspirations had leaned over his shoulder offering advice; Morris’s website Stupid Ad satirised the banality of their craft.) In Hawke’s Bay, Morris got involved in the local music community, helped revive and co-manage the legendary Cabana venue, mixed bands, and played with many local acts. He also wrote and recorded ‘Come On The Bay’, an anthem for Sports Hawke’s Bay. Morris spent his down-time curating his archives, sharing demos and rare recordings at his encyclopaedic website igMusic.co.nz, alongside humorous, nostalgic essays that described his musical coming of age, plus studio tips and aphorisms (a favourite was “You can’t polish a turd”). In 2006 Th’ Dudes reunited for a hugely successful nationwide tour, with their former idols Hello Sailor and Hammond Gamble as the support acts.

The loss was felt nationwide when Morris died in Napier, aged 53, on 7 October 2010. For over 30 years he contributed to New Zealand music, recording hit records as an artist and producer, filling halls around the country as a musician. Despite this high profile, being a backroom wizard suited his self-sufficient personality; in Th’ Dudes, Peter Urlich and Dave Dobbyn could divert the attention away, and as Tex Pistol he had a part-time persona. Due to the intimate nature of studio work, he made close friends with a large and varied number of New Zealand musicians. And by bringing the highest standards to recording New Zealand music, he touched anyone who enjoyed a pop song that was crafted to be popular.

--

Ian Morris on All the Young Dudes

Ian Morris on recording Murray Grindlay’s solo album