Initially with engineer Ian Morris as his wingman, Aickin produced more artists than he can call to mind. Besides records by Murray Grindlay, Bunny Walters, Richard Wilde, Rob Guest, The Neighbours, Broken Dolls, Jacqui Fitzgerald and Dave Dobbyn’s first post-Dudes singles, there were demos and sessions for Gerard Smith, Street Talk, Sharon O’Neill, Who Slapped John, and the North Shore Accordion Club, to name a few.

His philosophy was simple: “It was just manipulating everything and getting everyone in the right mood to capture the feel, you know, is really what it was all about; just creating the atmosphere, you know, getting everything to fall in place at the right time. That’s how that worked.”

Bands were queuing up at Stebbing’s to spend their own money on a sprinkling of the Aickin-Morris magic.

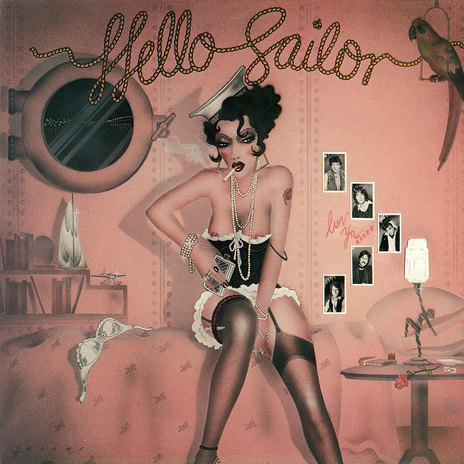

The resounding success of Hello Sailor et al meant bands were queuing up at Stebbing’s to spend their own money on a sprinkling of the Aickin-Morris magic. “I was full-time at it; one after the other, and the more success we had, the more work we got. It was just a big advertisement for Stebbing’s really.

“A lot of the bands that came in to do demos, they were self-funded. They’d pay the studio and I would just be thrown in on the act, if you like. So, a lot of that happened, where they were paying to do demos in the hope that I’d pick it up or something like that. I’m just in the studio looking at them while they’re doing their thing. Get them all set up, run through it, and that was it. There was no production going into it, as such.”

For all the hits there were just as many misses. South Auckland husband-and-wife Cimeron’s ‘It’s So Easy’ did nothing. “That was a great track. I was quite surprised that one didn’t do anything. We tried to pull a lot of stops out to get them going.”

Bunny Walters’ cover of the Ted Mulry Gang’s ‘Crazy’ was “not a good song, not my choice”, while The Totals’ ‘Total Man’ with a voiceover guy reciting the verses was “bizarre”. As for The Royales’ B-side, ‘Robot’: “I have never heard it before, or I was completely bombed! Not a bad song though!”

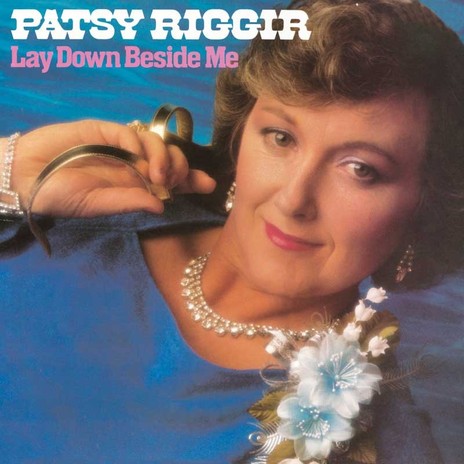

Aickin rated the two platinum-selling Patsy Riggir albums as the best work he had done. Even after quitting his poor-paying position at Stebbing’s he was coerced back as a freelancer to produce the second LP before turning his back on the music industry altogether.

“That was my grand finale, if you like,” he said. “I walked away from it at that point in time, regretfully. There was nowhere else to go and no offers came in. I didn’t have the money to launch myself as self-employed or anything like that so, unfortunately, kissed it all goodbye.”

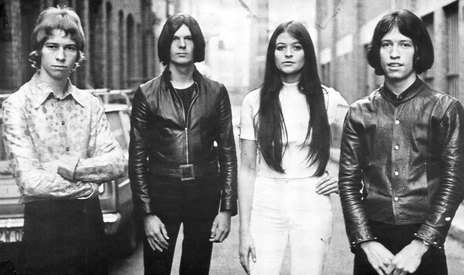

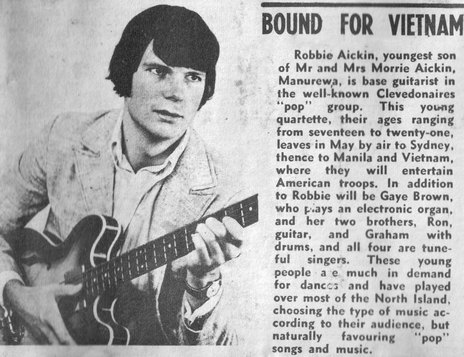

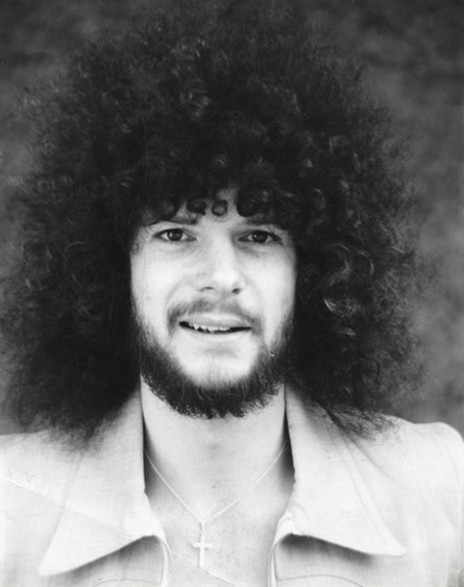

Rob Aickin was bass player in The Clevedonaires when they moved to Australia in 1968 and became The Cleves. They relocated to London in 1971 and changed their name to Bitch. When the band broke up, Aickin got to work in a lot of London’s top studios with some of the best engineers and producers on the scene.

“I learned a lot from all those guys because we’d lay down some rhythm tracks or something, being the bass player, and then I would end up just sitting in the control room, taking it all in and watching the engineers and the producers and how they were doing stuff and how they were recording. That’s where I really learned all the stuff.”

After he returned to New Zealand in December 1976, Aickin met with former Clevedonaires agent Benny Levin, who suggested he pay a visit to Eldred Stebbing. Stebbing tasked Aickin with making the newly recorded Murray Grindlay album sound “more commercial”. Stebbing liked what he heard and employed Aickin as the Jervois Road studio’s in-house producer.

Robert Charles Aickin was born February 1, 1948. His uncle Bob Ewing played double bass in Epi Shalfoon’s Melody Boys at the Crystal Palace Ballroom before being hired by Frank Gibson in 1956 as part of Auckland’s first professional rock and roll group, Frank Gibson’s All Star Rock’n’Rollers.

There were piano lessons while Aickin was at primary school but when he was at Manurewa High School he built his own electric guitar. The neck bent up like a banana but Aickin saved the money he made as a trainee draftsman at Gummer, Ford, Hoadley, Budge and Gummer, and bought a Jansen Invader and a Simpson amplifier.

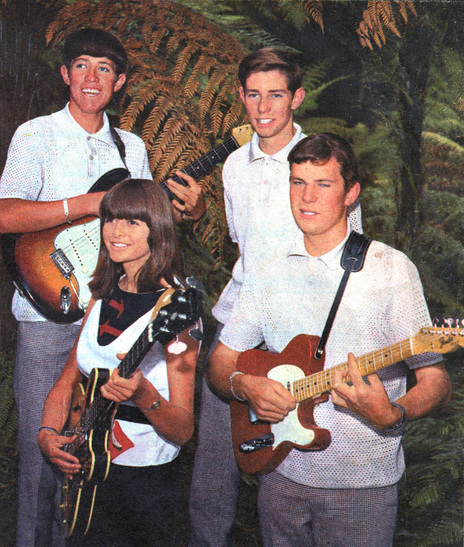

He took lessons from jazz guitarist Dave Donovan and joined The Four Quarters with lead guitarist Murray Partridge, bassist Dave Walkinshaw and drummer Dave Brown, becoming the lead singer by default. But his sights were set on the most accomplished of the South Auckland bands, The Clevedonaires.

The Four Quarters’ first gig was opening for The Clevedonaires at the Anglican Church hall in Papakura. The fact that Aickin could sing and play guitar stuck in The Clevedonaires’ memory and when their rhythm guitarist Milton Lane left, they asked Aickin to audition.

The Clevedonaires already had a recording contract with Benny Levin’s Impact label and their first release with Aickin on board was The Poppies’ ‘He’s Ready’ b/w The Yardbirds’ ‘Lost Woman’ in 1967. Not long after, bass player Gaye Brown bought a Vox Continental organ and Aickin switched to bass.

The Clevedonaires were about to perform for troops in Vietnam when Saigon was bombed.

Their next singles were recorded at the Stebbing Recording Studio in Saratoga Avenue, Herne Bay, before accepting a contract to perform for the troops in Vietnam. Days before their departure Saigon was bombed and The Clevedonaires instead headed for Australia.

Hooking up with Harry Widmar’s Cordon Bleu booking agency, the newly named The Cleves moved from Lucifers to the Plaza Hotel in the heart of Kings Cross and Rob Aickin and guitarist Ron Brown started writing their own songs. Their first joint effort ‘Don’t Turn Your Back’ was the B-side to their debut Festival single ‘You And Me’, produced by Pat Aulton.

The Cleves became a top draw card in Sydney and Melbourne and recorded an experimental LP for Festival with producer Richard Batchens. In 1971, they followed the lead of The La De Da’s and Max Merritt and The Meteors, and headed for the United Kingdom. During the voyage there aboard the Angelina Lauro, they changed their name to Bitch, simply to create a bit of controversy and attention.

After a showcase gig at the Speakeasy in London where the band unveiled a new collection of Aickin-Ron Brown material, WEA signed Bitch to a recording deal with a £10,000 cash advance. They were put together with American session guitarist Jimmy Ryan (Carly Simon, Loudon Wainwright III) as producer and began recording at Morgan Studios in Willesden.

The first single ‘Good Time Coming’ reached the top five in the Netherlands, West Germany and Sweden. The follow-up single ‘Wildcat’ was recorded at Apple Studios in Savile Row. Neither release cracked the British charts. English electronic group UNKLE sampled ‘Good Time Coming’ for their 2007 album track ‘Restless’.

Despite great reviews in the UK music press, Bitch weren’t catching on in their adopted home. At the same time, WEA underwent a major restructure that meant Warners, Elektra and Atlantic would go their own ways and the completed Bitch LP would be scrapped.

Aickin and Ron Brown were invited to audition for a new heavy rock group being put together by Island Records around former Spooky Tooth singer Mike Harrison: Raw Glory. They recorded three songs, including Aickin and Brown’s ‘Black Rider’ and ‘Easy’ but it too fell apart.

“We got tied up with a guy called Guy Stevens, who was a crazy record producer back in the day,” Aickin recounted. “And he was involved a lot with Procol Harum and Mott The Hoople. He’s the guy who came up with those names.

“We got kicked out of a few studios. It was just right out of control, let’s face it. There was cocaine all over the place. It was just an absolute bizarre mess at the end of the day. All the talent was there, but there was no one with a straight head to pull it all together.”

Aickin and Brown made one last attempt to resurrect something from their UK adventure when they recorded a demo with Muff Winwood at Island Studios. Nothing came of it, but what did happen while Bitch and Raw Glory hit the wall was that Aickin got to look on at some of the top studios as engineer/producers such as Winwood, Jimmy Ryan, Tony Ashton and Chris Kimsey plied their trade.

It stood him in good stead when he returned to New Zealand in December 1976 with new wife Val, whom he had met during The Cleves’ days in Australia. Sent by his former band’s agent Benny Levin to visit his former band’s producer Eldred Stebbing, Aickin surmises: “I just stepped in the right place at the right time with the right information and knowledge, I suppose.”

Stebbing revealed that the studio had just done an album with roots singer-songwriter and jingles writer Murray Grindlay and played Aickin some tracks. Aickin told Stebbing the production wasn’t gimmicky enough to get airplay and that he could make it sound more commercial.

“I JUST STEPPED IN THE RIGHT PLACE AT THE RIGHT TIME WITH THE RIGHT INFORMATION AND KNOWLEDGE, I SUPPOSE.”

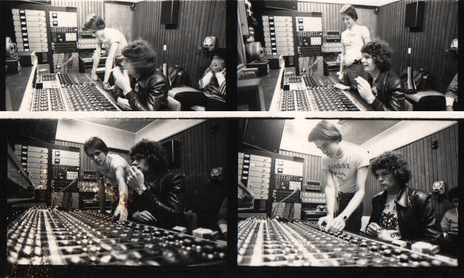

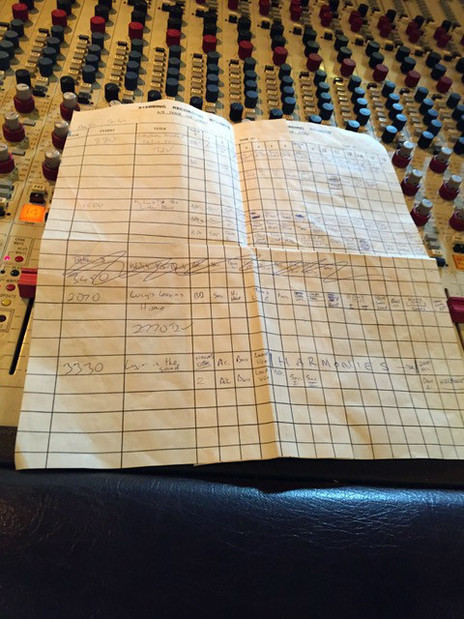

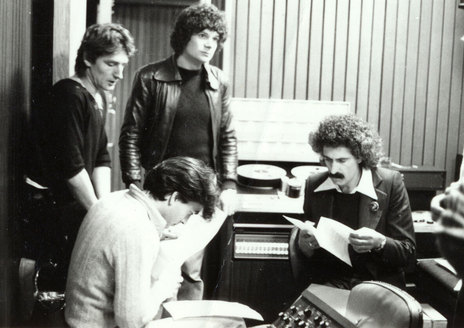

“That was my first leg in,” Aickin said. “That was the first time I ever met Ian [Morris]. Went down into the A Studio, ‘Well, okay, I’m gonna remix Murray’s album.’ I hadn’t even heard it. I had nothing to do with the recording of it. Simply a remix, put on the 16-track, in those days, and remix it and see what I can come up with. So that’s exactly what I did.

“It showed him [Eldred] what I could do with the studio, I suppose, rather than just come up with something that was just raw, basic music. For me, the whole purpose is to sell records, not just to make a record for your own enjoyment, and I think that’s what Murray was sort of doing. I sort of went in and threw a big commercial bucket of water at it, basically.”

Stebbing was suitably impressed and hired Aickin as Stebbing Recording Studios’ in-house producer as well as giving him a sales rep position selling Zodiac’s dated Māori and Pacific Islands library to tourist shops in the top half of the North Island. The sales job only lasted around three months. Aickin’s commercial bucket of water did no good for the self-titled Grindlay album. It was released, with Aickin credited as producer, later in the year but failed to make any waves.

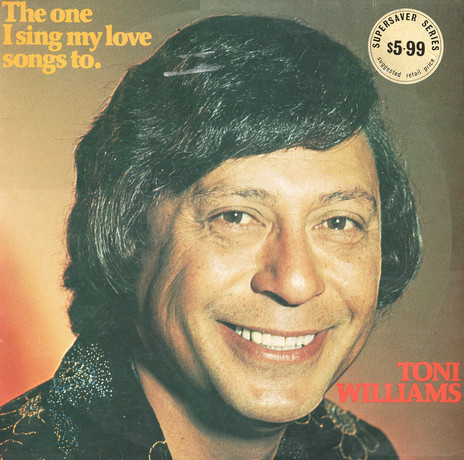

Aickin’s first full production of his own came soon after with a single for rejuvenated country crooner Toni Williams, who was coming off the success of the Peter Posa-penned-and-produced ‘Rose (Can I Share A Bed With You)’.

Williams and Festival Records managing director Ray Porter had picked out the then unreleased ‘The One I Sing My Love Songs To’, by Nashville writer Wayland Holyfield. Presented with a cassette, Aickin immediately roped in Grindlay’s ace jingles/album band of Red McKelvie, Neil Edwards, Peter Woods and Dennis Ryan. Julian Lee arranged the strings.

“I used to like using Red and that, because they lived in the studio. They knew their way around,” Aickin said. “They were good and they were fast at picking things up too. I’d say, ‘Do this,’ and they would do it. Saved time and a lot of effort.

“The idea we came up with was country crossover stuff, so trying to make it as commercial as possible, because it was raw country music. So gave it that commercial edge.” With the single going gold and peaking at No.9 on the national charts, an album quickly followed. Also titled The One I Sing My Love Songs To, it too went gold.

Aickin and his right-hand man Ian Morris were on their way. “Ian was only just a new boy on the block at that point. He was pretty green, but he sort of knew his way around the studio. But we just sort of clicked straightaway.

“So no one argued with us, and Eldred just let us go to it in the end. I remember coming down into the studio and saying to Ian one day, ‘Mate, we can do what we like,’ and we did. That’s how it all came about really with Hello Sailor and all that. We really just had a free run and we did it. As long as we didn’t interrupt with Murray Grindlay’s studio time. We had to work around him because someone was paying for that!”

It was during Grindlay’s downtime that they got Hello Sailor into the studio, initially to lay down some demos. Aickin talked the band into making some changes with the arrangements and the band were pleased with the results.

“Ian was very good with the scissors too, editing. And a lot of those tapes like Hello Sailor were just edited to pieces, left, right and centre. We’d use, like, the same chorus over and over and cut it together and splice it. Some of them, you’d watch the tape going through and it was just editing tape after editing tape going through.”

Often the run-throughs became the takes. “The thing was capturing it; making sure the tape was rolling. Because you never knew when they were going to perform, if you know what I mean. But fortunately, one of my rules was, ‘Make sure the tape’s running, Ian.’ We always had the tape running with groups like that because you never knew when you were gonna get it, and if you didn’t get it, you’d lost it, you’d have to come back another day and try again.”

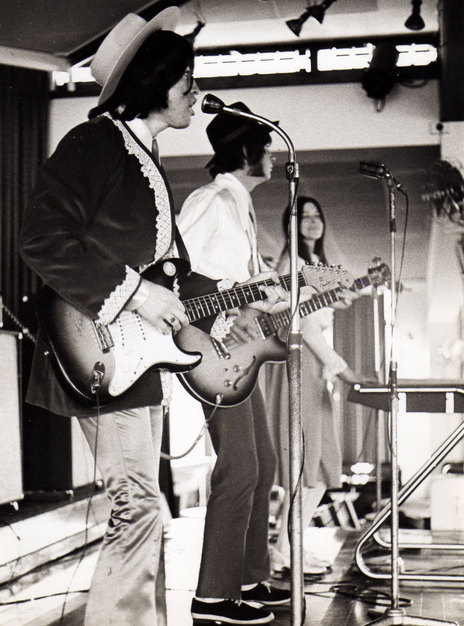

Hello Sailor’s ‘Gutter Black’ and ‘Blue Lady’ heralded a new sound for New Zealand rock music.

An early habit was taking home a cassette tape to listen to progress and plan the next move. The studio had a small transmitter and after completing a mix they would broadcast it through the transmitter and listen outside on a car radio before going back to make adjustments. “That was what all the 5k, 6k boosting was all about, was to get it to jump out of your little transistor.”

When Hello Sailor and singles ‘Gutter Black’ and ‘Blue Lady’ were released, they heralded a new sound for New Zealand rock music. The band was embraced by Radio Hauraki and even got some regional airplay thanks to Aickin popping in to radio stations while on his Zodiac sales trips. Again, the album went gold. Aickin also produced Hello Sailor’s second album, Pacifica Amour.

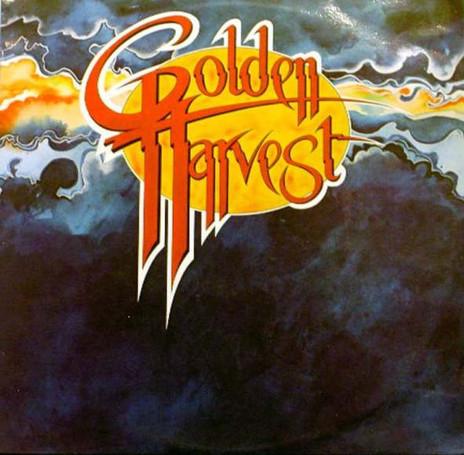

The greatest impediments to recording Benny Levin’s latest discovery Golden Harvest were the presence of Levin’s business partner Russell Clark, a producer in his own right, and drummer Mervin Kaukau’s propensity for overplaying. The former problem was solved when Aickin politely told Clark to “piss off”, but the latter took more time.

“I had to take all the drummer’s drums away and just left him with a snare drum and bass drum, and overdubbed all the other stuff, because he was so busy trying to impress me with drum fills and stuff like that,” Aickin remembered. “Took his whole kit away because he couldn’t resist hitting them.”

The standout track was the disco-leaning ‘I Need Your Love’. But when it came time to mix down, Aickin recognised the song needed something more and invited keys player Mike Harvey to help figure out what. Taking advantage of a Moog synthesiser left by another band, Harvey came up with the now familiar riff that helped propel it to No.7 on the New Zealand singles chart and gold status. “We knew when we found it, that was it, and it came to be the hook of the song,” Aickin said.

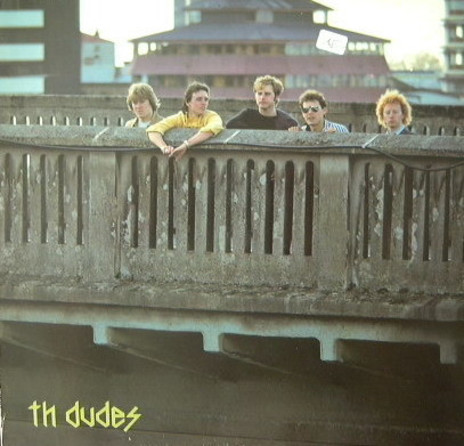

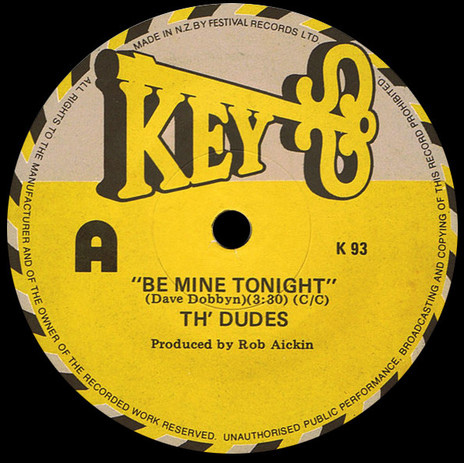

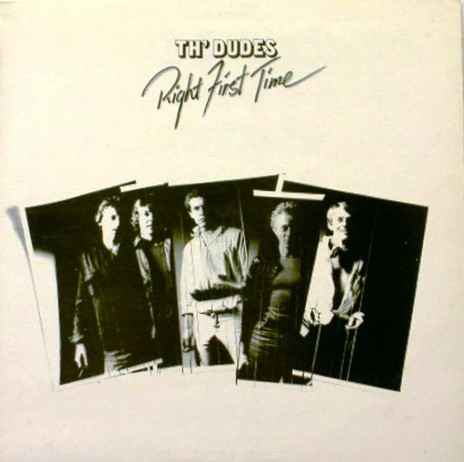

Recording Th’ Dudes brought an end to the Rob Aickin-Ian Morris partnership. “My only regret is that he left to join Th’ Dudes really. I wish we had stuck together and moved to Australia, or something like that. We would have done really well. But he wanted to be a rock’n’roll star at that point in time, so off he went.”

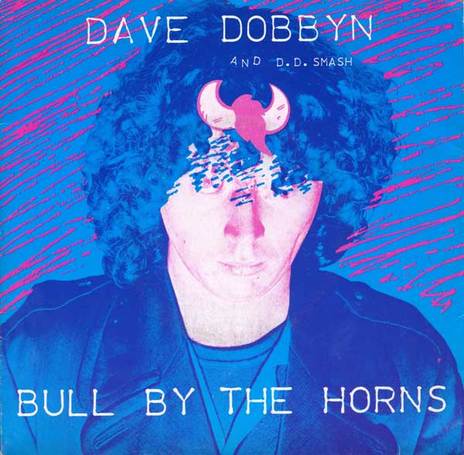

What puzzled Aickin most about Th’ Dudes was that guitarist Dave Dobbyn was not their lead singer. “Dave was the one with the voice. It stuck out so much.”

With Morris busy on guitar, Aickin also engineered much of Th’ Dudes’ sessions with new assistant engineer Denis Odlin. Aickin mixed the tracks while the band were on the road, playing them the results on their return. He produced Right First Time while the follow-up album Where Are The Boys is credited to Aickin and Morris.

Aickin also played a considerable hand in renaming two of the band’s biggest hits that were originally titled ‘Piss’ and ‘Quite Frankly’. “Yes, that was my call. I convinced the boys radio would not play ‘Piss’ and suggested ‘Bliss’. ‘Be Mine Tonight’ was also my suggestion. I can’t remember what it was originally but it was a bit obscure.”

After the demise of Th’ Dudes, Aickin and Morris got to work more closely with Dobbyn, demoing his solo material during Stebbing’s downtime. ‘Lipstick Power’ and ‘Bull By The Horns’ were both released on Epic but any thoughts of pulling an album together came undone when Dobbyn refused to sign with Eldred Stebbing.

“Ian went his own way and I went my way and Dave went his way, and that was the end of that.”

“There were quite a few people who wouldn’t sign with Eldred, for obvious reasons,” Aickin revealed. “Then the whole thing sort of fell to bits at that point in time. Ian went his own way and I went my way and Dave went his way, and that was the end of that.”

Other Aickin productions went unreleased after the act wouldn’t put pen to paper. Polynesian vocal group Southern Transit’s cover of Hello Sailor’s ‘Lyin’ In The Sand’ was a classic, according to Aickin, and Ramon York’s post-Ragnarok unit Who Slapped John “would have been like the next Hello Sailor”.

Aickin believed the sticking point was Stebbing lacked the required clout outside of New Zealand. “Eldred didn’t have the international contacts in the right places to get those things released. It was Eldred’s weak point, I think; he didn’t have the promotion there. It was only when he was working with Festival or CBS, where they had the machinery in place to promote, that the success was there.”

Patsy Riggir did sign with Stebbing and her sessions in the early 1980s were a dream. Tony Moan had replaced Ian Morris as house engineer and Aickin once again utilised the core of Murray Grindlay’s studio band, primarily guitarist/pedal steel picker Red McKelvie.

“Tony Moan was the house engineer then. So he was … he didn’t have that creativity [of Morris]. He was more like old school, a very technical engineer, where Ian was more creative in the engineering department. So when you get the technical engineer, everything technically was perfect; and with Red, with the country authenticity, it was very easy to put together in that way.

“Patsy was brilliant. One or two takes and that was it. She was really, really professional. I mean you didn’t have to do two takes sometimes because she was so good. She knew what she was doing and so much feel, it all just came out just so easy. And that’s why it would sound so good, because it was all natural.”

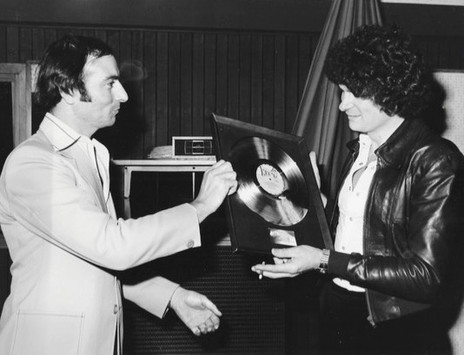

‘Lay Down Beside Me’ peaked at No.3 on the New Zealand singles chart at the end of 1981 and, soon after, the album of the same name went platinum. Aickin had already quit his job at Stebbing’s and was the factory manager at a polystyrene company in Onehunga when Stebbing begged him to produce Riggir’s follow-up, Are You Lonely. It included the timeless ‘Beautiful Lady’ and was another platinum record.

“I just walked away after that because I wasn’t getting paid properly,” Aickin said. “I was getting paid a wage, that’s all I ever got, and he wouldn’t cut me in any commissions whatsoever, or royalties, not a cent. And from the day I left I have never received one cent royalty from all that stuff I did, and that’s why I walked away.

“Sometimes I wish I’d hung in there, but I would have ended up just being their engineer and probably have to work my way through. Because we’d burnt up all the acts; all the cream had been taken off the top and basically had to sit around and wait for the next wave to come through, if you like.”

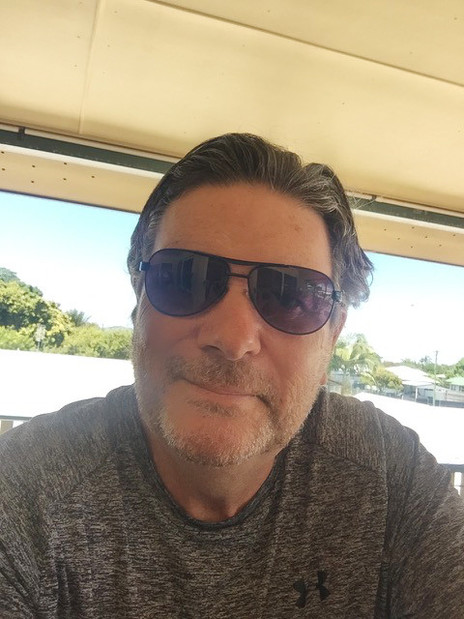

Aickin moved his family to Queensland in 1989 where he has run his own cleaning and polystyrene packaging businesses and worked as a real estate agent. In early 2004, he built his own home recording studio but found that the industry had changed too much.

“I guess I was just trying to fulfil a little void in my ego or whatever the case may be, just some self-satisfaction,” he said. “And in the end, I just started writing songs and recording myself just for fun. Just because I could, I suppose.”

AICKIN: THE PRODUCER IS “SO CLOSE TO EVERYTHING, AND YET NO ONE SEES IT.”

In 2014, Aickin was diagnosed with multiple myeloma bone marrow cancer. He was in remission but the disease returned late in 2021. “I’ve had about eight multiple crush fractures in my spine, so my back is absolutely shot. I was gonna have a hip replacement but I canned it because the cancer’s sort of coming back a little bit, but they’re not treating it just yet. Yeah, physically I’m fucked.”

Occasionally he allows a little bitterness to creep in that his contribution to the New Zealand recording industry has gone largely unacknowledged, but mostly he is as content as his health allows him to be.

“You’re so close to everything, and yet no one sees it. You’re doing everything, you’ve basically come up with the recording and put it all together, and yet it goes unnoticed, or unrecognised, a lot of the time. The producer maybe gets blamed if it’s a flop; if it’s a success it’s the artist’s success.”

--

Read more: Rob Aickin, the man with the Midas touch