Talking with Eldred Stebbing was like being with a living encyclopaedia of New Zealand music history. He had sharp recollections of local musical culture going back to the 1930s, and the social and technological changes in the decades since. But he kept returning to the present, especially the technology. One got the impression that, rather than talk history, he would have been happier to dismantle the hard-drive recorder, then rebuild it to his own upgraded specifications.

I had two long conversations with Eldred in the mid-2000s, when he was in his mid-80s but still coming into the office most days: the legendary recording studio on Jervois Road, Herne Bay, opened in 1970. Downstairs, the large, green-carpeted main studio had witnessed the creation of music that became the soundtrack of New Zealand in the 1970s and 80s. Early recordings by Split Ends, Bunny Walters, and Dragon, John Hanlon’s big hits, and Murray Grindlay’s biggest jingles (the Crunchie Great Train Robbery ad, the BASF Dear John ad). The drum sound of ‘Gutter Black’ and bass riff of ‘Bliss’ from the confident albums of Hello Sailor and Th’ Dudes. Stored somewhere were the 78s, 45s and tapes of early New Zealand pop by Esme Stephens, Mavis Rivers, Ray Columbus, The La De Da’s, The Underdogs, recorded in Stebbing’s earlier studios in the 50s and 60s.

Eldred Stebbing was born in 1921, into a musical family. He began working with sound technology when he was a child in the 1930s, fiddling with crystal radio. In his first job, he assembled valve radios; in his last decade the family company to which he devoted his life was manufacturing DVDs.

In conversation with him, topics diverged and intersected: recording the visits of US jazz star Artie Shaw and first lady Eleanor Roosevelt during World War II, the talent of producer Julian Lee in the early 1950s, getting the speeches at the opening of the Harbour Bridge down on tape, the recording of the tympani on ‘Till We Kissed’, the campaigns to break bands into Australia in the 1960s, and the polished recordings of Hello Sailor and Th’ Dudes in the 70s, and Patsy Riggir in the 80s.

Always there were comparisons to technology of the present: the firm’s state-of-the-art CD/DVD plant, the inadequacies of the early plasma flat-screen TV sitting on the other side of the room.

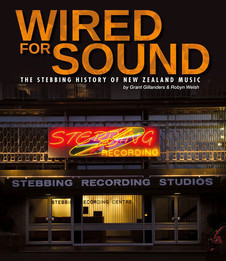

All this history is captured in a lavish book published by Bateman in November 2019: Wired for Sound – The Stebbing History of New Zealand Music. The authors are Grant Gillanders – well-known archivist whose label Frenzy has reissued a staggering number of New Zealand recordings – and Robyn Welsh, a journalist and researcher married to Vaughan Stebbing. Vaughan now runs the Stebbing company in partnership with Robert, Eldred’s older son.

As well as being a history of the recording of New Zealand popular music, mostly from Auckland artists, the book works as a social, cultural, family and business history. It is also a fascinating account of how technological changes have shaped the quality of recordings and the way we consume them.

The images below are compiled from Wired for Sound and AudioCulture’s digital archive; any quotes from 2006 are from the recording sessions I did with Eldred. He embodied living history; simultaneously, all around him a future history of local music was being created.

--

In the late 1940s, when the fledgling Stebbing’s Sound System was based in Eldred’s family home in Avondale, live recordings were made down the phone line from venues in Auckland city. This acetate is a rare recording of the Epi Shalfoon band, one of the most popular in the city. Eldred explained the primitive system in 2004: “I had the landline so it could be patched to the town hall or wherever I wanted it, but it was mostly because its fulltime job was working through Wardlaw Advertising in the National Mutual Building in Shortland St. Only having the single line you’d test for voice level and run through the commercial then you’d ring the handle with five seconds [warning], and in you’d go with the cutting, direct cutting.” – Dennis Huggard archive, Alexander Turnbull Library, MSD12-0142

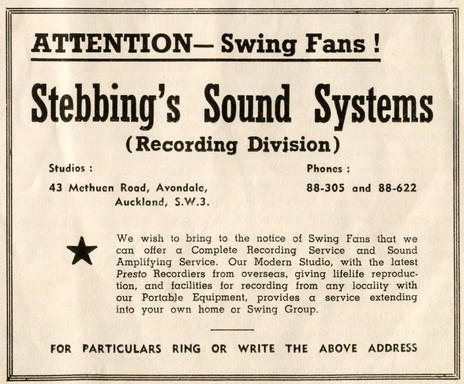

In August 1946, Stebbing’s was confident enough to advertise its services in the first issue of Jukebox: New Zealand’s Swing Magazine, August 1946. The company could record from live venues using portable equipment, or from the Avondale studio using a Presto direct-to-disc recorder. The studio at 43 Methuen Road, Avondale, was used for private recordings and advertisements, not commercial discs. Often between 60-80 radio ads were made a week. – Dennis Huggard collection

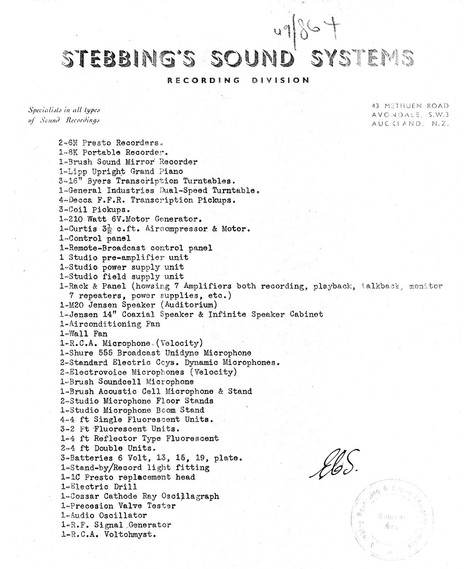

In late 1949 Stebbing’s Sound Systems was soon to become the Stebbing Recording and Sound Company, and base itself in the Pacific Buildings on Queen Street. A list of equipment at the Avondale studio before the move included Presto recorders – direct-to-disc, about the size of a dishwasher – 16” turntables, a cathode ray oscillograph (measuring current and voltage), and several microphones made by companies such as RCA and Shure. – Stebbing archives/Wired for Sound

Dale Alderton, Crombie Murdoch, and Julian Lee: three of Auckland’s jazz stars performing at the Town Hall concert chamber, 7 August 1950. Among the other performers was Mavis Rivers, and tin-whistle player Hughie Godon. The event was billed as Auckland’s “first jazz concert” as the music was for listening rather than dancing; it was promoted by Bruce MacDonald, a drummer with great energy and enthusiasm for the jazz scene. (In 1994 the concert was released as a cassette by Ode, and eventually on CD.) Eldred Stebbing said in 2006 that Murdoch was “in demand because he was a very versatile sort of pianist, you could fit him in as an accompanist or do anything. Julian could do the same.” At this concert, Lee played alto sax throughout the night as part of the core band, plus a virtuoso showcase in ‘Messin’ Around’, soloing on tenor, trombone and trumpet. For the early 50s period that Stebbing recorded in the Pacific Buildings, Lee was the firm’s musical director. – Alderton family archive/Wired For Sound.

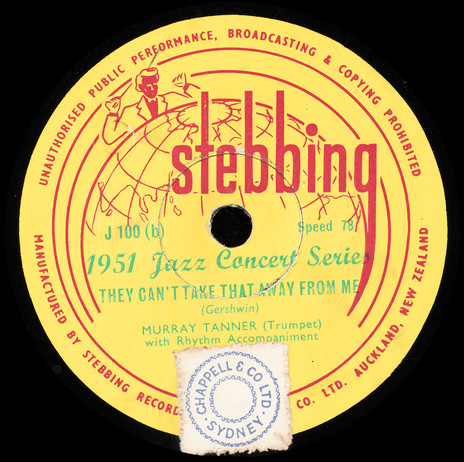

Auckland jazz trumpeter Murray Tanner’s rendition of Gershwin’s ‘They Can’t Take That Away From Me’, released on 78rpm disc as part of Stebbing’s brief “Jazz Series”, 1951. Tanner told me in 2007 that he also performed it at the Mercury Playhouse around this time, with George Campbell on bass. “My lasting memory of that concert was in the middle of my ballad there was a loud bang and behind me there was George Campbell on the wooden platform, nearly tripping himself over. He had of course been drinking sherry out of a beer glass.” Three discs were released in the Jazz Series, but it was significant, archivist Dennis Huggard says in Wired for Sound: “No one was really interested in recording local jazz music at the time and without Eldred and Phil at least tipping their hats to that genre then we would be left with very little local jazz from that period.” – Dennis Huggard archive, Alexander Turnbull Library, MSD10-0332

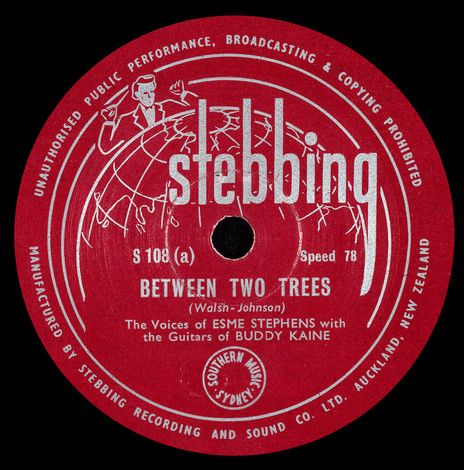

Esme Stephens’s 1951 recording of ‘Between Two Trees’ was one of the Stebbing label’s biggest hits, selling over 7000 copies (in the US, the original had only been a minor hit for the Andrews Sisters). It was Stebbing’s first release using a tape recorder. “Esme was an excellent vocalist,” Eldred said in 2006. Hits were rare, but helped the company’s strategy of establishing the studio and label. “You had good ones, you had bad ones, I mean ‘Between Two Trees’, Esme Stephens did quite well on that one. The quantities were never expected because when we were manufacturing ourselves you only had two presses and if you had a full week of pressing you were doing very well.” Dale Alderton, Stephens’s husband at the time, and partner in the vocal trio the Duplicats, described her as “a romantic singer, she liked Rosemary Clooney and Ella Fitzgerald, of course. All those marvellous singers were part of her in-built repertoire.” – Dennis Huggard archive, Alexander Turnbull Library, MSD10-0335

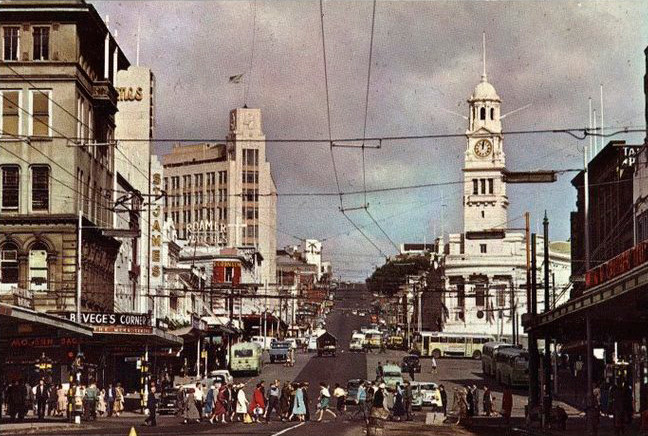

The east side of Queen Street, 1955, showing the Pacific Buildings (Bevege's Corner) at left and 'Doctor at Sea' playing at the St James Theatre. Zoom in at Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 580-01970

The hub of the fledgling New Zealand music industry in the 1950s was in Pacific Buildings, at left, opposite the Civic on Queen Street, Auckland. From the early 1950s the Stebbing studio was on the fourth floor, and in the same building was the Musicians Union, run by Tom Skinner, and Southern Music, the US publishing firm whose local representative was ebullient swing drummer Wally Ransom. He would wander upstairs and encourage the recording of Southern/Peer titles such as ‘Mocking Bird Hill’. Pacific Buildings was demolished, and replaced in 1966 by the modernist ASB building still on the site. – Gladys M Goodall collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-7756-1-121

The control room in Stebbing’s Pacific Buildings studio, 1950s, where the company moved after its beginnings as a home-based studio in Avondale. Among those who recorded there were Mavis Rivers, Esme Stephens, Julian Lee, Johnny Granger and Bill Wolfgramm. “This was no backyard studio with egg cartons on the walls,” says Robert Stebbing, one of Eldred’s two sons, in Wired for Sound. Inside, the walls were lined with plaster tiles for sound absorbency, and a 12-foot stud added to the audio qualities. “The control room wasn’t hugely big, just enough room for the mixing panel really, but it was the best at the time. The speakers with their angled fronts were mounted above the viewing window that looked into the studio.” The echo chamber was more primitive, however, as echo units did not yet exist. The Pacific echo chamber was the toilet, which had to be checked for occupants before recording began. – Stebbing archive/Wired for Sound

‘The Midnight Train’, Johnny Granger, from 1951: an early 78rpm country and western release on Zodiac; on the A-side was Hank Williams’s ‘Cold Cold Heart’. Granger, “the Yodelling Drover”, was a dairy farmer from southeast of Auckland. In Wired for Sound Stebbing engineer Steve McGough mentions Granger coming into the studio in the 2000s, with copies of his 78s to be digitised. “Johnny talked about how he’d been working on the farm in Hunua all day and his mother would pack him some sandwiches for dinner that he could eat on the drive up to Auckland in the days before the motorway. He’d head into Queen St and up the stairs and they’d have time to run through the songs a few times with the musicians and then it was one shot at recording to disc. It was one take straight to disc because of the cost of the discs.” – Dennis Huggard archive, Alexander Turnbull Library, MSD10-0206

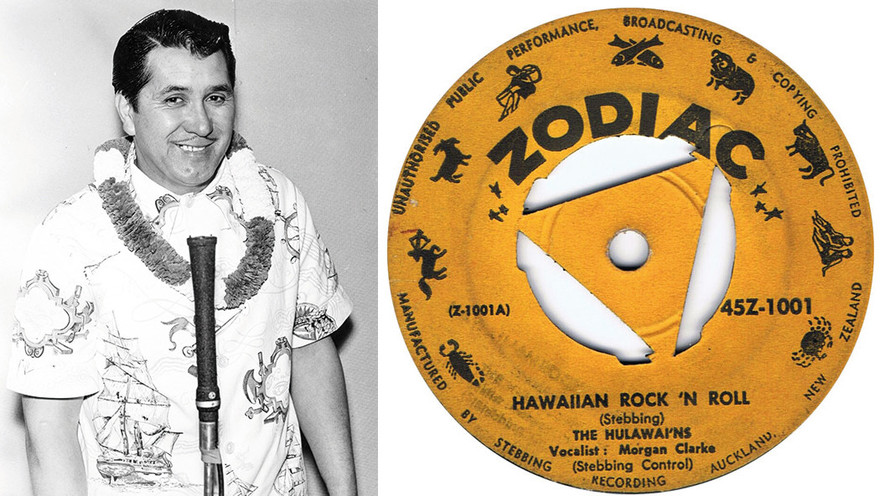

‘Hawaiian Rock’n’Roll’ from 1957: the first disc on Zodiac to be released on 45rpm disc as well as 78rpm. The singer was Morgan Clarke, and the song was written by Phil Stebbing, Eldred’s older brother. The Hulawai’ns wanted an original song, Eldred explained in 2006. “Phil was a very good pianist, and very good organist, to the extent that sometimes when he was doing PA jobs at the Town Hall and somebody’s accompanist hadn’t turned up or something had happened, he would go out and sight read and that person would perform with him. He would play it absolutely accurately.” The Hulawai’ns were the resident group at the Point Chevalier Sailing Club in the 1950s. In Wired for Sound their drummer Jim McLeod recalls the recording was made in the club on a sweltering hot day. The group found it difficult to perform without an audience, and Eldred and Phil found it difficult to get a decent take; the windows and doors were shut because of outside noise from swimmers and seagulls. After many takes, there was finally one everyone was happy with. “Whenever I hear the record today,” says McLeod, “all I hear is that echo of an empty hall with a handful of people in it. The record must have done quite well. I received a royalty cheque shortly afterwards for 6/8.” – Bill Sevesi collection/Wired for Sound; Simon Grigg collection

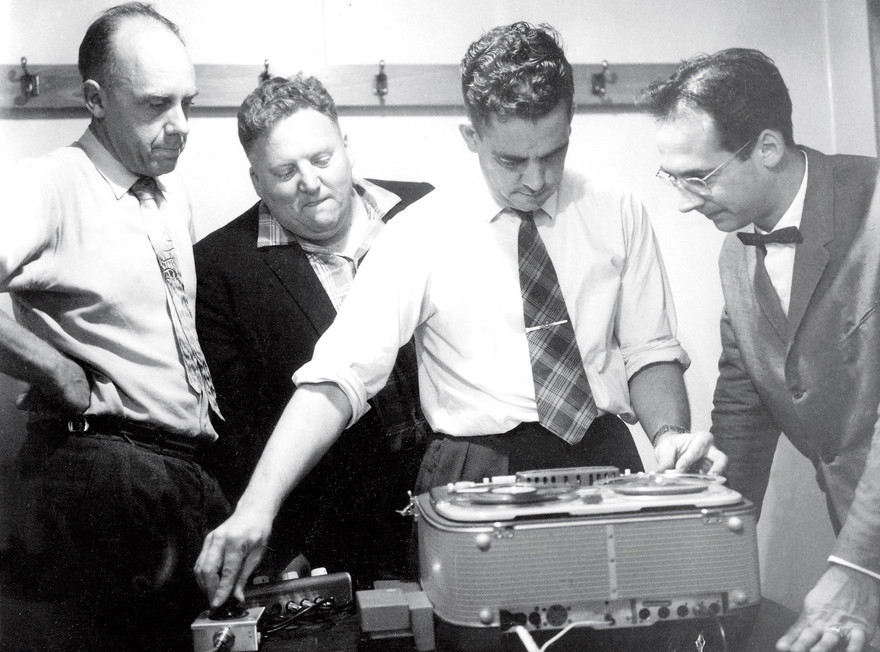

Four stalwarts of the Auckland pop music industry, pictured at a 1959 session for Eddie Howell at the Sandringham school hall. From left: Phil Stebbing, pianist and bandleader Jock Nisbet, Eldred Stebbing, and Benny Levin. The A-side of the Zodiac single from the session was ‘Teenage Baby’, credited to The Voices of Eddie Howell with the Jock Nisbet Group. The B-side was Spectoresque in its ambition: ‘When It’s Springtime in the Rockies’, by Eddie Howell with the Choir of the Auckland Choral Society. The backing trio featured well-known musicians Dorothea Franchi on harp, Silvio De Pra on accordion, and double bassist Bob Ofsoski. – Eddie Howell archives/Wired for Sound

In the late 1950s Eldred Stebbing’s nemesis was 1ZB programme manager Dudley Wrathall, who had worked in broadcasting since 1927. When rock’n’roll arrived, Wrathall fought an idiosyncratic battle to keep it off air – especially local releases. Less conservative staff waited until Wrathall was on the bus home before they played any of the offending discs. But for Eldred Stebbing, Wrathall’s disdain had more serious consequences: it meant his Zodiac recordings rarely received airtime. He recalled that in Wrathall’s office after his retirement “when they pulled the carpet up they found that the floor was completely covered with local 45s.” The attitude was, “Why should we play local records when we can play the top overseas artists?” ZB historian Bill Francis commented, “Dudley had the lumpiest carpet at 1ZB.” – Chris Bourke collection

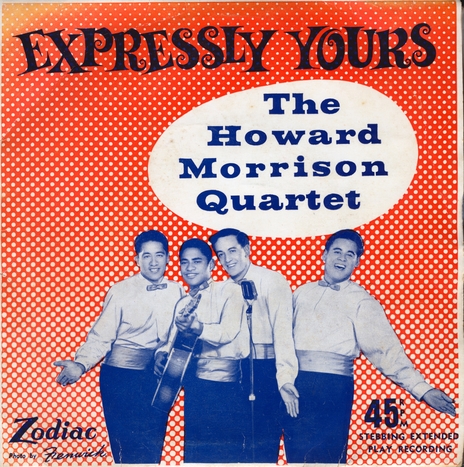

The Howard Morrison Quartet’s third EP on Zodiac, Expressly Yours, was recorded in Auckland with the Jock Nisbet Group in 1958. Besides ‘Gum Drop’ and ‘Tumbling Tumbleweeds’, it featured a song called ‘Be Mine Tonight’ by Sunny Skylar, a recent US hit for Andy Williams. Twenty years later a song of the same name, but by Th’ Dudes, would be one of Stebbing’s most perennial radio hits. – Simon Grigg collection

A trio of Polynesian stars at the Orange Ballroom, Auckland, in the early 1960s. From left: Daphne Walker, George Tumahai and Bill Sevesi, with drummer Merv Herdson and guitarist Ricky Santos. Sevesi was first recorded by Eldred Stebbing in the late 40s, just a demo at the Methuen Road studio. By 1957 Sevesi was in his prime, leading the band at the Orange, and recorded his own rock’n’roll song ‘Go Man Go’, credited to Bill Sevesi and his Novelty Five, with Morgan Clarke; the B-side was ‘Christmas Time’, by Auckland writer Gene O’Leary. It was Sevesi’s only Zodiac release – and the label’s first to be on 45rpm disc only. But over 40 years later Sevesi and Stebbing reunited when the lap-steel guitarist recorded a commercial in the Jervois Road, and Eldred invited him to use downtime in the studio to record an album, at no cost. Pacific Paradise, the CD which resulted, featured a rare guest vocal from Daphne Walker. – Bill Sevesi archive/Wired for Sound

The Kini Quartet, from Gisborne, was an act that Zodiac had a lot of success with in the early 1960s. Their biggest hit was ‘Under the Sun’, by local songwriter Margaret Raggett. After winning a talent quest in Gisborne, they approached Eldred for an audition. In 2006 he recalled: “They were a very, very smooth group as far as their singing went, with an entirely different approach to the Howard Morrison Quartet. That was the reason we did it.” The Kini Quartet’s debut Zodiac 45 was Raggett’s ‘Hard Times are Comin’, recorded in Gisborne’s 2XG radio station in December 1961. Peter Posa, a Zodiac artist at the time, played guitar. – Gisborne Photo News

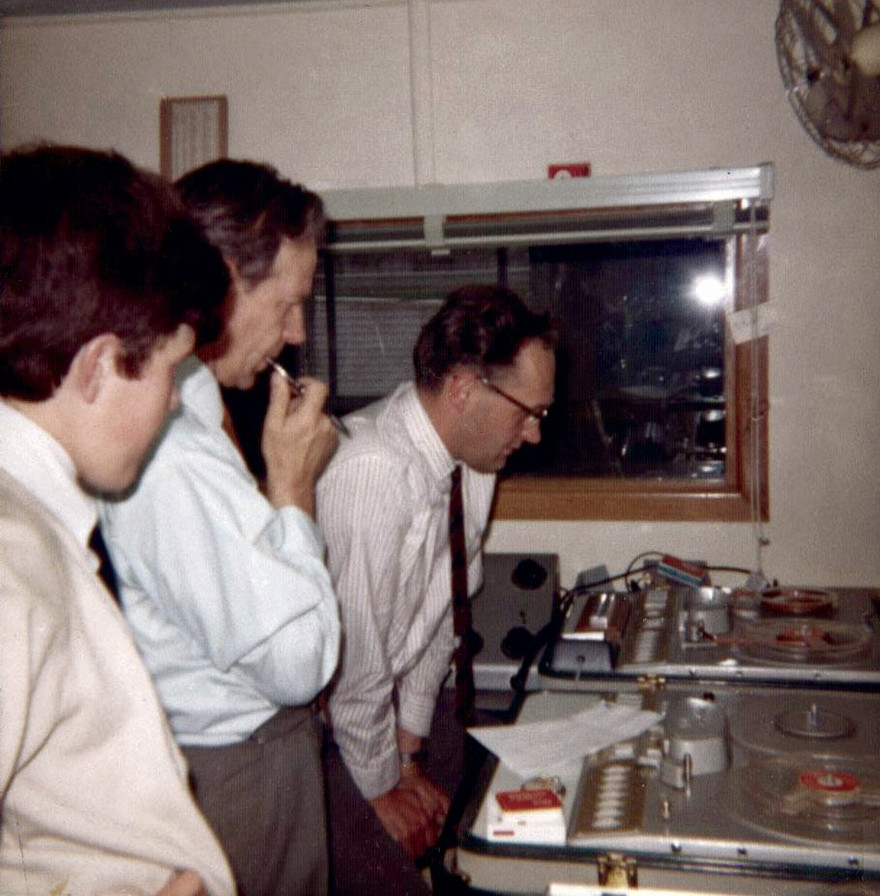

John Hawkins, seen here on the right at the Saratoga Avenue studio, was one of Stebbing’s star engineer/producers of the 1960s. From England, he joined the firm in 1963 after working as an engineer in London, reportedly with producer Joe ‘Telstar’ Meek, Winifred Atwell, and Petula Clark. During his years with Stebbing’s, he engineered some of the most legendary releases on Zodiac, by artists such as Ray Columbus and the Invaders, The La De Da’s, Sandy Edmonds, Max Cryer and the Children, The PleaZers, The Four Fours and Tommy Adderley. He is pictured here on the right c.1967, during a PleaZers session. The pen-sucker is unidentified; on the left is long-serving Stebbing engineer Tony Moan, then an apprentice. “John had finesse, in anything he did,” Eldred recalled in 2006. “He was a very technical person. He’d walk in, and if he didn’t like the drums he’d tell the drummer to go and get a new set of drums, or hire them. He’d say I am not wasting my time. But he had a lot of techniques.” Eldred and Hawkins once worked together in the Auckland Town Hall recording a concert by the Auckland Choral Society, and the pair read from the score, anticipating when to bring the soloists up in the mix. “He would balance on ‘God Save the Queen’.” – Dennis Gilmore collection/Wired for Sound

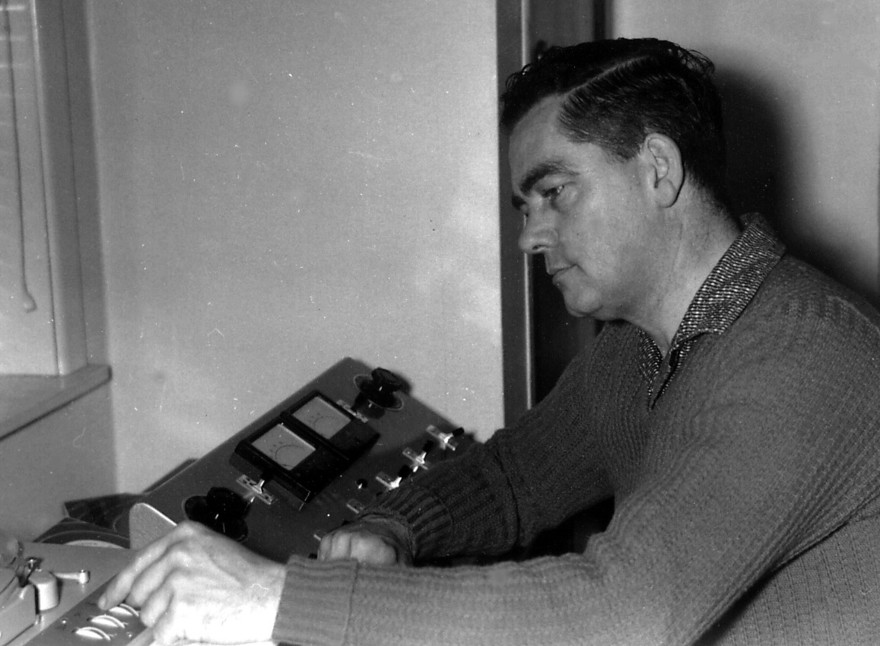

Immortal tracks recorded by Stebbing’s in the 1960s – ‘Till We Kissed’, ‘She’s a Mod’, ‘How is the Air Up There’, ‘Tropic of Capricorn’ – were all done in the basement of a suburban brick-and-tile house in Saratoga Avenue, a cul-de-sac in Herne Bay. The Stebbing family lived upstairs. In 2006 Eldred said the home studio was only an interim measure, but it lasted a decade from 1959 to 1970, when they built the Jervois Road studios. Space was an issue downstairs – about 20 foot by 12 foot – and although council consented, they were conscious the studio was in a residential area. “The studio in Saratoga was under the house, which was excavated out underneath, and the control room and that were all built separately and the studio, it wasn’t that big. When we did Ray Columbus’s ‘Till we Kissed’ there, the tympanis couldn’t come through the doorway, they were too wide, and we had to have them out in the garage. We left the door open on the garage outside and we got round it. We were only working with two tracks, and so you would record the actual song on one and then your overdubs would go on the other track. Alternatively we would copy from one machine to the other with the overdubs. Later on when stereo came in it was so easy to do it. Of course [later] the four-track machine, there wasn’t room in the control room for it, so it was upstairs on remote control. We also had the organ upstairs, it was a Conn electric organ we had at the time.” Eldred is pictured here in the downstairs control room at Saratoga Avenue. – Simon Grigg collection

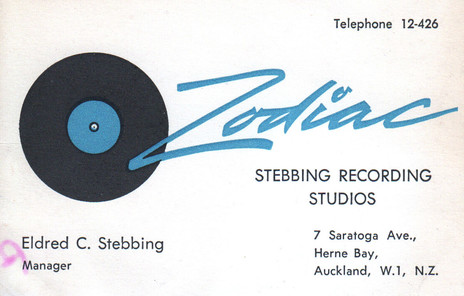

Eldred’s business card during the 1960s, when the studio was based in the family home at Saratoga Avenue. Wired for Sound quotes Max Cryer, who recorded with his children’s choirs there: “Margaret, Eldred’s busy little wife, being also the secretary of the recording company, ran up and down the stairs managing the house, her family, the studio, the company, her dog, who was as busy as she was, my children, me, the technicians and the hundred and one things which had to be done.” – Simon Grigg collection

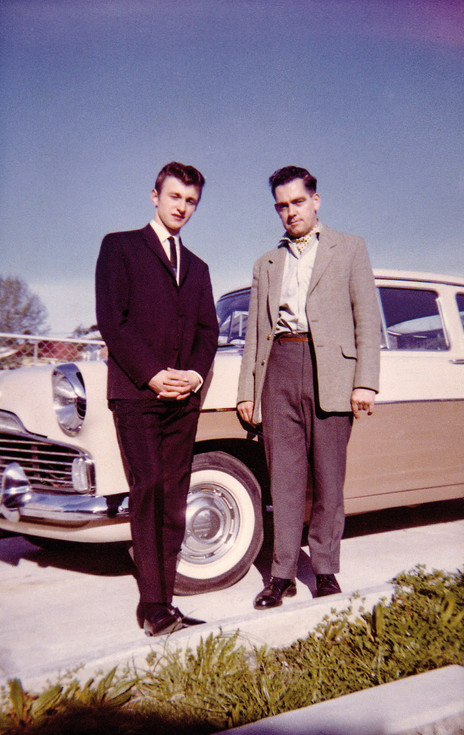

Ray Woolf with Eldred Stebbing and the latter’s pride and joy, his Ford Zodiac, c.1962. Woolf had been in New Zealand only one month when he signed to Zodiac, after a night in which he stepped up to sing with The Keil Isles and found himself approached by the club owner, offering a regular spot, and Eldred, discussing a recording contract. Just 18, he was already well experienced as an entertainer in the UK. In New Zealand he was soon touring as a support act for Helen Shapiro, and recording at Saratoga Avenue backed by the Invaders. Ray Woolf collection/Wired for Sound

Eldred Stebbing of Zodiac with the 1965 Loxene Golden Disc award for ‘Till We Kissed’, recorded by Ray Columbus and the Invaders. Looking on is Fred Noad of Allied International, here representing the New Zealand Federation of the Phonographic Industry (now known as Recorded Music NZ). ‘Till We Kissed’ had reached No.1 twice that year in the country’s unofficial national and regional charts. The 1965 Loxene Golden Disc was the inaugural event, and the winner of best song was voted for by the public. – Simon Grigg collection

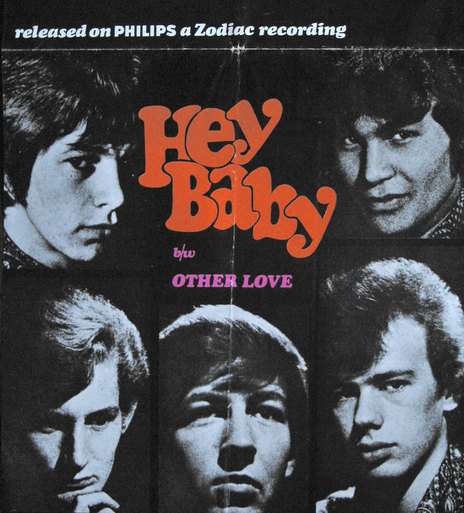

A promotional flyer for The La De Da’s’ 1967 hit ‘Hey Baby’, a song suggested to them by John McCready, the A&R man of Philips, who licenced it from Zodiac. The irresistible song, originally by US singer Bruce Channel, was produced by Claude Papesch. The novelty telephone call in it – with Da’s drummer Trevor Wilson speaking in a camp voice – was suggested by engineer John Hawkins, who was a big fan of the Goons. ‘Hey Baby’ knocked the Beatles’ ‘Penny Lane’ off the No.1 spot and remained there for two weeks. – Simon Grigg collection

Sandy Edmonds, sandwiched between Eldred and Margaret Stebbing, at the Saratoga Avenue studio in 1966, during the recording of ‘Come See Me’. The PleaZers, who wanted to record the track themselves, provided the backing track and vocals. Edmonds then performed it on tour through New Zealand with the Yardbirds, Roy Orbison, and the Walker Brothers, and in the pilot episode of TV’s C’mon. Through her TV appearances – and relentless marketing by manager Phil Warren – Edmonds became the “it” girl of 1966-67. “The cooperation was alright with television,” Eldred recalled in 2006, “I think it was a lot better than what it is today. Because they had to put something live to air, so where were they going to get it from, so they had to use New Zealand artists to do that.” – Rosalie Corner collection/Wired for Sound

In 1970 Eldred Stebbing realised a lifelong dream by opening a state-of-the-art recording studio, built to his own specifications after years honing his expertise in acoustics, equipment and studio design. When opened at its prime location on Jervois Road, Herne Bay, the building had two studios, one recording in eight-track, the other in four-track. Plus, there was a mastering and dubbing suite, a metal and electronics workshop, and a three-bedroom apartment on the top level for the family. Within a few years, recordings were made in 16 track and then, in 1977, 24-track: just in time for the debut Hello Sailor album. – Vaughan Stebbing/Wired for Sound

The main studio at Stebbing’s Jervois Road facility. The perimeter walls are of Tawa timber, built with a faint curve, with cavities packed with absorption material. Large vertical membrane absorbers, or bass traps, are installed above the Tawa walls to absorb lower frequencies. The ribbed ceiling also has sprayed-on acoustic absorption material. The original control room is through the angled window above the orange chairs (this later became the B commercial studio when a larger control room was built behind the piano). – Stebbing archives/Wired for Sound

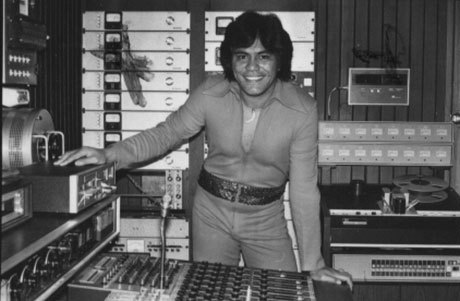

Bunny Walters, photographed in the Jervois Road studio control room in July 1977, about the time he was recording ‘Crazy’/’Help Me Out’ for Impact. Behind him to the left is the back of eight compressors built to Eldred and Robert Stebbing’s valve and solid-state design. Beside the compressors is a rack of amplifiers designed and built by Robert, as was the recording desk. Around this time, a photo in Wired for Sound shows, Walters was backed in a recording session by Lisle Kinney and Ricky Ball of Hello Sailor, and Ian Morris of Th’ Dudes. – Impact/AudioCulture

Robert Stebbing at the disc cutter in the Jervois Road studio in the 1970s. Eldred built a small heating unit into the stylus to warm it as it cut an acetate, to reduce surface noise. He also added a vacuum system to suck away the “swarf”, the residue from the cutting process. – Stebbing archives/Wired for Sound

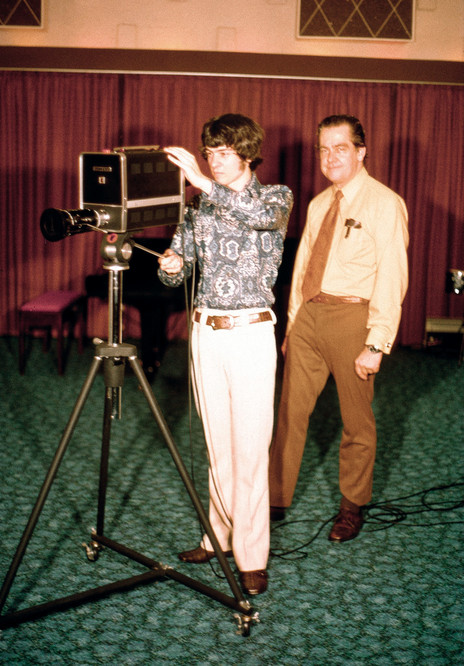

Vaughan Stebbing, with his father Eldred, in the main studio of the Jervois Road facility. Vaughan has long been a keen photographer, and Eldred was an early devotee of Super-8 movie cameras. Vaughan is quoted in Wired for Sound that his father “always believed that you could do absolutely anything yourself and he didn’t necessarily believe that you needed to do it through formal education. He believed that if you had the energy, the drive, the passion and the commitment for something then you could go and find out about it, ask the questions and go for it. He believed that anything that wasn’t working could be fixed and that you could achieve anything you wanted to achieve. It was all down to your attitude. That was how we were brought up.” – Stebbing archives/Wired for Sound

Just two months after their debut in December 1972, Split Ends entered the Jervois Road studio to record their debut single, ‘For You’. In 30 minutes it was in the can. “We listened back and it felt very, very good,” wrote Mike Chunn in 1992. With ‘Split Ends’ as the B-side, and mixed at HMV studio in Wellington, the single was released in April 1973 on Vertigo. Pictured are, from left: Tim Finn, Mike Chunn, and Phil Judd. The unseen drummer is Div Vercoe, a ring-in from Hamilton. – Mike Chunn archive/AudioCulture

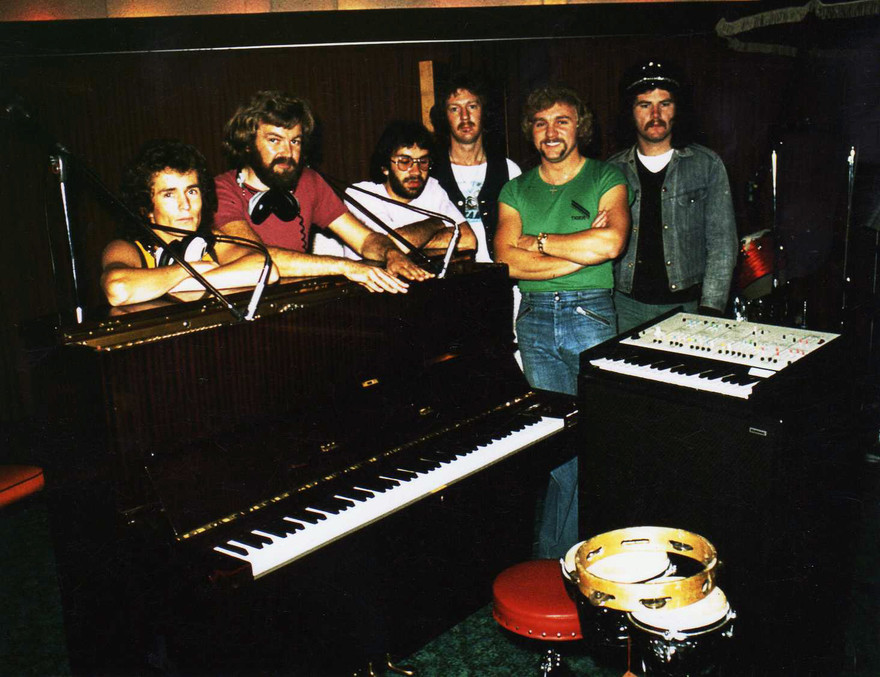

In the mid-1970s the band Salty Dogg recorded its own music as well as providing backing music for John Hanlon’s hit albums. At the time Mike Harvey, seen here in the green t-shirt, was running hot: from 1973 to 1977, he produced the winning song for five consecutive Apra awards, all recorded at Stebbing’s. From left are: Graham Chapman, Vic Williams, engineer Phil Yule, Martin Winch, Mike Harvey and Chris Gunn. – Vic Williams collection/Wired for Sound

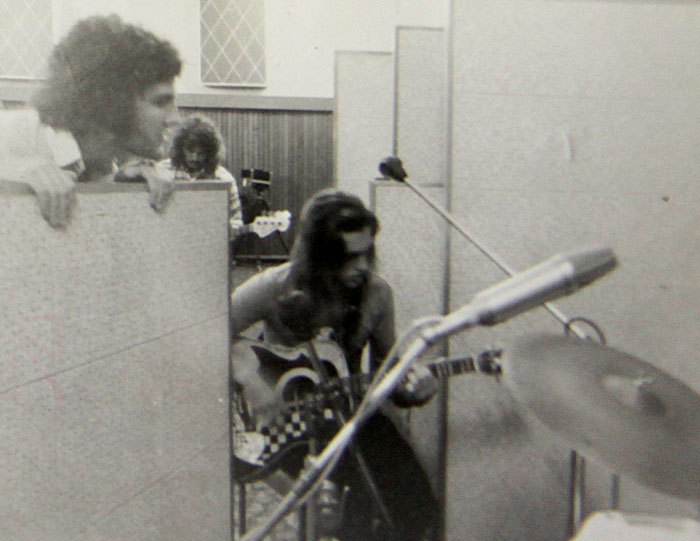

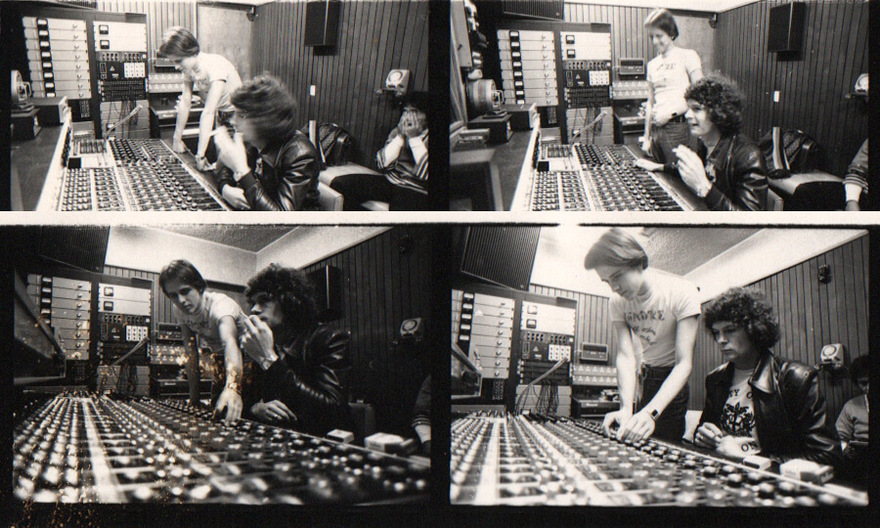

Wired for Sound describes the formation of the mid-70s in-house “studio dream team” of engineer Ian Morris and producer Rob Aickin. Together they worked on a string of award-winning and hit albums by Hello Sailor, Golden Harvest, Th’ Dudes, Toni Williams, and Dave Dobbyn. In the mid-60s Aickin had recorded at Stebbing’s Saratoga Avenue studio with the Clevedonaires, who later evolved into the Cleves then, in the UK, to Bitch. He recorded in several top UK studios, and returned to New Zealand in 1977, looking for production work. Eldred Stebbing recalled Aickin in 2006: “He was very good, he could work the people very well, and he could get the cooperation of people. He was a different producer to what John Hawkins was; John was finesse, in anything he did. But Rob was more get the feel of it, like he was in the group, and do it that way. Rather than being a manufacturing sort of personality.” Morris was immediately impressed by the creative, iconoclastic way Aickin used the technology. Aickin and Morris are seen here recording the debut Hello Sailor album at Stebbing’s, 6 June 1977. – Simon Grigg collection

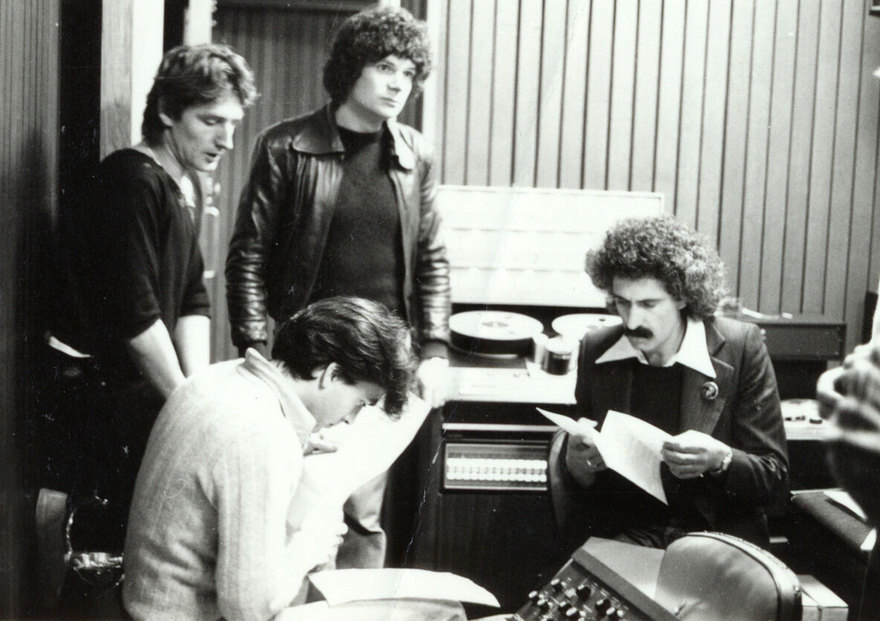

Hello Sailor’s Dave McArtney and Harry Lyon, sitting, with producer Rob Aickin, standing, and their manager David Gapes. In Wired for Sound Harry Lyon describes his revelation at the way Aickin and Morris worked together on ‘Gutter Black’: “Instead of telling us how the song should be, even though it was rough, they were able to show us how it could sound and it suddenly sounded like a radio song. The arrangement got sharpened up and the big snare sound came in during the final recording.” – Murray Cammick

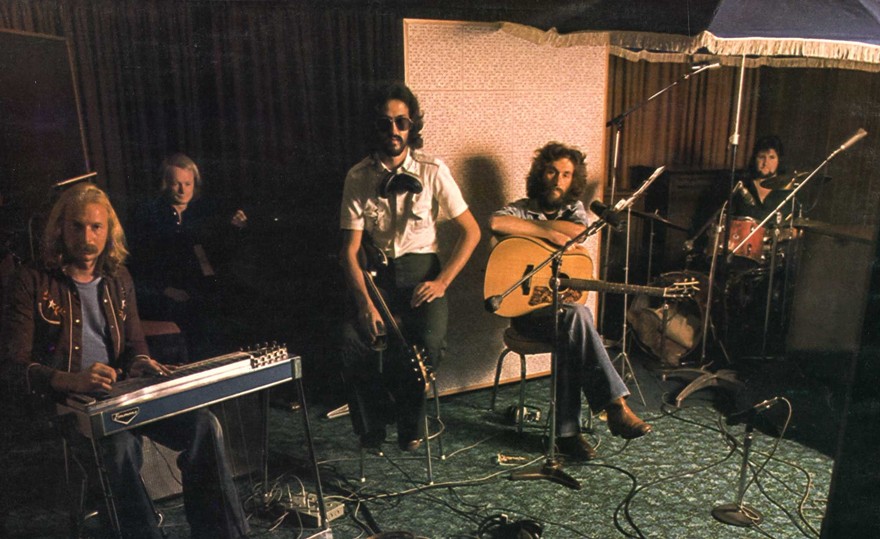

Recording jingles underwrote the Stebbing studio in the 1970s and 80s, and the king of jingles was Murray Grindlay, who had recorded for Zodiac with the Underdogs in the 1960s. By the mid 70s he was on a long roll, with ads such as ‘Dear John’, and Crunchie chocolate bars. In 1990 came ‘Welcome to Our World’, sung by John Hore for Toyota. According to Wired for Sound, “Such was the demand for Murray’s jingles that he’d be working with Red McKelvie as his musical director and pianist Murray McNabb and fine-tuning the jingle for the next session while the client was waiting in reception. At the same time, the engineers were in the control room completing the final mix of one they’d just recorded.” Several of the musicians Grindlay often used for advertising sessions are pictured here while recording his 1977 solo album. (See Ian Morris’s comments on engineering the album, here on AudioCulture.) From left: Red McKelvie, Peter Woods, Neil Edwards, Murray Grindlay, and Dennis Ryan. – Key Records

Country singer Jack Riggir was one of the earliest artists on the Zodiac label in 1951, so the success of his daughter Patsy Riggir in the 1980s was especially satisfying to Eldred Stebbing. Four of her albums reached platinum level sales. Producer of the first two, Lay Down Beside Me and Are You Lonely, was Rob Aickin. In Wired for Sound he says Riggir only needed two or three takes to capture the mood of a song. “With Red McKelvie as musical director, all I had to do was make everyone feel comfortable and feel the moment.” Pictured in the mid-1980s celebrating one of Riggir’s platinum albums on Epic are, from left: Eldred and Margaret Stebbing, Patsy Riggir and her mother Betty. – Simon Grigg collection

In August 1999, with Eldred about to enter his 80s, the company took a leap of faith by building a state-of-the-art CD manufacturing plant in Ponsonby. It was almost 50 years since Eldred had cut his first shellac disc. The equipment inside the new multi-storey building gave them the means to master, replicate, print and package discs, and then despatch them. A few years later, the plant was expanded to manufacture DVDs. – Steve McGough/Wired for Sound

Eldred Stebbing passed away in 2009, aged 88, six years after his wife Margaret. As the closing pages of Wired for Sound discuss the ambitious venture into digital manufacturing, the dynamic of the family business is explained. Every new idea came about after rigorous debate. “It was a reality that would see each of them take their own thoughts back to their respective work areas. Margaret would head back to the front reception desk where, in the days before computers, she entered client bookings in the diary in pencil and picked up her pen in the evenings and weekends, to write out invoices by hand. Vaughan and Robert went back to their respective studio sessions and workshop maintenance and development projects. Eldred was invariably back in his office or out on the road, taking on an increasingly consultative role, with one ear on the goings-on in the studios and the other honed for new recording opportunities.

“Such was the rhythm of Stebbing’s business/family life as it tracked its way into cassette, video and CD and DVD production, alongside its studio artists.” In 2023 the company began manufacturing vinyl albums again. (photo: Simon Grigg collection)

--

Wired for sound - The Stebbing History of New Zealand Music by Grant Gillanders and Robyn Welsh (Bateman, 2019)