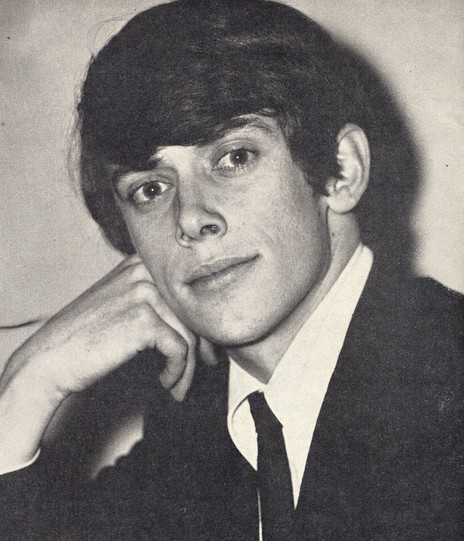

Raymond John Patrick Columbus was born 4 November 1942 in Christchurch, one of seven children. His father Jack was a hotel worker, his mother Cressey a milliner at Ballantyne’s department store. Jack’s ancestry was Greek, Creesey’s Irish. They lived in a Woolston state house, and Cressey worked in the cafeteria of a panel beater and on the sweets counter at the Avon cinema.

It was a humble upbringing, but he was born to perform. The family was musical: Jack played harmonica and Cressey was a very good whistler, idolising Ronnie Ronalde. Jack had returned from the war early, with sand-damaged lungs after fighting in the Middle East. He worked as a bartender, and later managed hotels; he was fond of a drink, but at heart he was an entertainer who loved any opportunity to get up and play harmonica or perform a burlesque comedy dance. After the war there were few opportunities, so when the pubs shut at 6pm, Jack tended illegal bars in after-hours venues, and wouldn’t get home until after midnight.

Jack insisted that his son was going to be the next Fred Astaire, and at the age of six Ray began singing and tap dancing lessons alongside his sister Patricia. They were partners at the competitions, but Patricia took all the prizes until Ray’s voice broke. Tap dancing taught him a love of performance and costume; he later took up ballroom dancing.

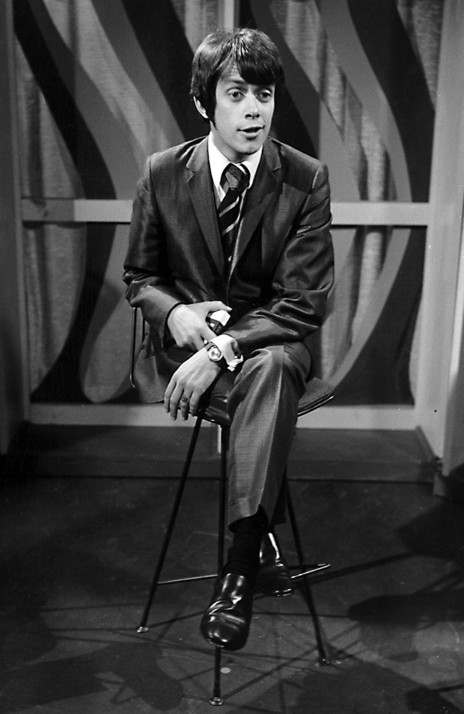

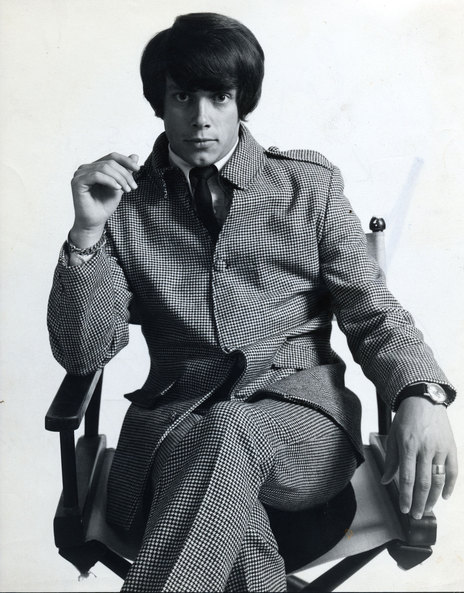

By 1955 he was a fashion-conscious, tap-dancing hipster, working at a cinema in Cathedral Square.

Columbus was a busy teenager. At Xavier College he excelled at soccer, becoming a Canterbury rep; he was an altar boy and a member of the choir. His first job, aged nine, was selling ice creams at the Avon. Once his voice broke, he found “some power and volume and confidence” and began winning many of the competitions he entered: solo tap-dancing, song and dance routines, duets.

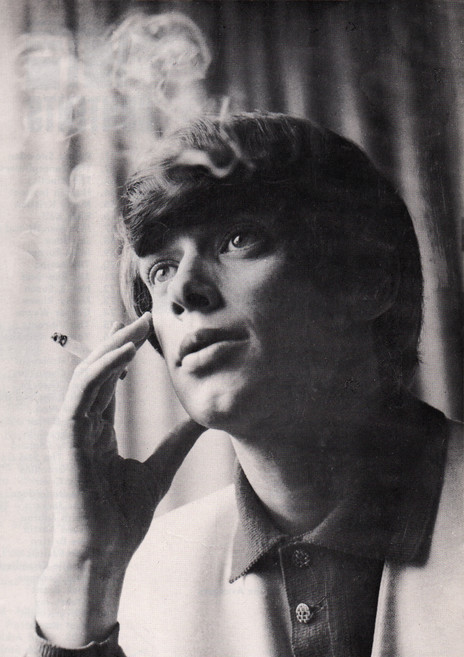

By 1955 he was a fashion-conscious, tap-dancing hipster, working at a cinema in Cathedral Square: three sessions a day on the weekends. “It gave me a chance to see movies that were illegal for someone of my age,” he recalled in 2006. “I was able to see Rebel Without a Cause, East of Eden and Blackboard Jungle long before I should have been allowed to. I saw Blackboard Jungle many times. That was where I heard ‘Rock Around the Clock’.” Elvis quickly took over from Fred Astaire as a role model.

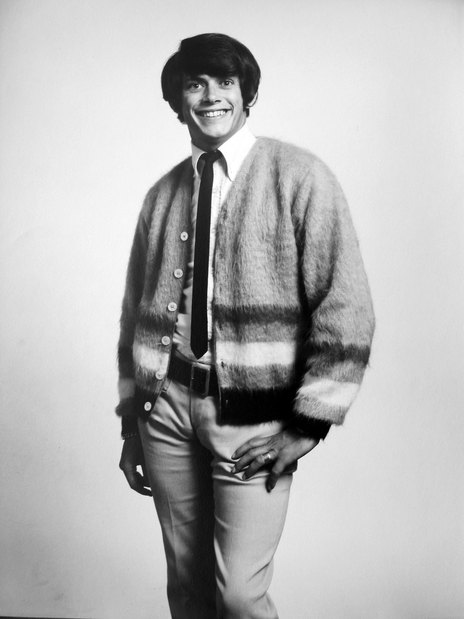

Columbus began borrowing film stills from Trevor King, a Kerridge-Odeon cinema manager who also road-managed many visiting artists’ tours. Guided by the photos, Cressey knitted her son jumpers, emulating the American look. He would hang out in Cathedral Square, leaning against a parking meter, wearing a frat-boy sweater with a big R on the front, jeans and brothel creepers.

On leaving school, Columbus joined the Inland Revenue Department. He started visiting the US Navy icebreakers at Lyttelton Harbour and buying American records, clothing and cigarettes from the sailors. (He started smoking at age six, fishing his father’s butts out of the fireplace, and eventually developed an 80-a-day habit.)

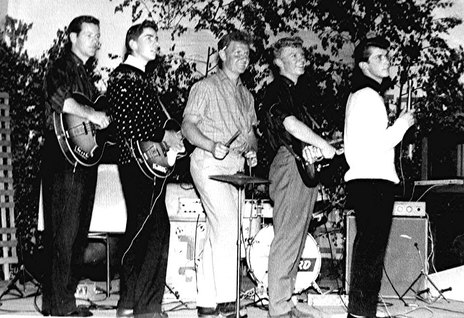

Towards the end of 1958 Columbus put together his first band with drummer Peter Ward, pianist Billy Kristian, and Andy Jones on guitar; their main influences were the Everly Brothers, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Buddy Holly. Calling themselves the Dominoes, their first gig was with Trinidadian boogie-woogie pianist Winifred Atwell.

Shortly afterwards, Kristian left to join Max Merritt and the Meteors, the city’s hottest band, playing the Hibernian and Caledonian halls, as well as its own youth club. Ward joined the Downbeats, who had the biggest gig in Christchurch: the youth dances at Spencer Street hall in Addington. One night, while playing at Sid Hollis’s Studio on Cashel Street, the Downbeats’ singer didn’t show up, and Ward told band leader Doc Foster to approach a boy on the dance floor. In 2009 Columbus told Kate Preece, “I got up in the next set, sang ‘That’s Alright’ in E and, as I recall, ‘Whole Lotta Shaking’ in C, and scored a regular spot with the band at Spencer Street every Saturday night from then on.”

The Downbeats were an old-school dance band, playing waltzes, valetas, maxinas, with Columbus performing a rock’n’roll bracket. Ultimately the band evolved into Ray Columbus and the Invaders. He said in 2006, “Our guitarist was a brilliant guy called Tony Athfield, and when he left I said, What are we going to do without you? He said, I’ve got my star pupil coming in, he’s only 14, his name is Dave Russell. He arrived in his school pants.”

The Invaders performed at the Bird Dog, a club for Operation Deep Freeze: US sailors who were heading to Antarctica. This exposed the group to R&B artists such as James Brown, Jackie Wilson and Ray Charles; Columbus also studied the dance moves of the black servicemen. When Cliff Richard and the Shadows toured New Zealand in March 1961, the Invaders were deeply impressed by their Fender guitars, Vox amplifiers and echo units, so they ordered a set of three fiesta-red Fenders. At this stage the line-up was Brian Ringrose and Dave Russell on guitars, Peter Ward on drums, Mac Jamieson on bass and Columbus on vocals – and they were rivals to Max Merritt and his Meteors.

Did Columbus’s father approve of his move into rock’n’roll?

“He didn’t accept it. But basically I convinced Mum particularly, and Dad just had to go along with it. Because I was 16 by that time, you couldn’t really stop me – but he did say that if things didn’t work out I could join the government. Within a year I had a TV show, Club Columbus – only four programmes but it was syndicated throughout the country. So immediately he saw something was happening, and there was still show business attached. It was entertainment, it wasn’t just rock’n’roll and so I’ve always had a foot in each camp.”

The Invaders became the resident band at The Plainsman, a club on Lichfield Street.

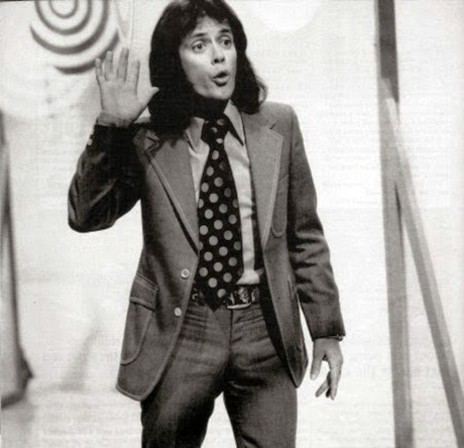

The Invaders became the resident band at The Plainsman, a club on Lichfield Street. Columbus put his dancing skills to use, choreographing the band’s movements. ‘It’s legend now’, he told Preece in 2009, “but promoters would come to town and catch our shows at the Plainsman and offer us deals to go to Auckland.” One night in 1962, the Howard Morrison Quartet was topping the bill at the Majestic, and the theatre manager John Hart told them about the Invaders. “So Howard came over after their show and caught ours. He talked me into going to Auckland – he said we’d ‘kill them’ up there – so we took one of the offers and he was right. We were the toast of the Queen City.”

The Invaders and Meteors arrived in Auckland almost simultaneously in December 1962, “just prior to the Beatles’ rise and the Shadows’ decline”. According to Grant Gillanders, “What started as a look-and-learn reconnaissance exercise quickly ended up as a seek-and-destroy annihilation of the Auckland club scene. Aucklanders fell in love with The Invaders’ sound from the first chord of their debut gig at the Shiralee nightclub, and within a few days the group was the talk of the town.”

They were soon offered six weeks’ work by Dave Dunningham, a leading Auckland promoter. “We took the place by storm then took the Phil Warren contract to open the Monaco in Federal Street. Phil also sold us to other clubs so we would play some nights at the Shiralee, Thursday nights at the Oriental, lunches at the Bali Hai and every Friday and Saturday night at the Monaco.”

Eldred Stebbing signed them to a recording contract with Zodiac. He later recalled, “To me they were the complete package with a great mix of American R&B mixed with Shadows style riffs. They looked as good as they sounded and in Ray they had a world class front man – someone who could interact with an audience.”

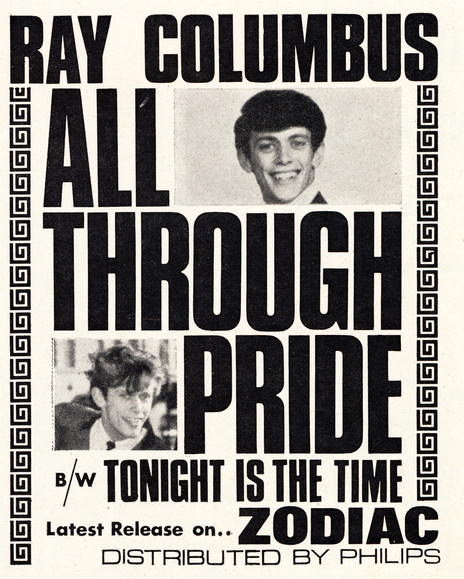

The Invaders insisted on recording their own songs, and their first release was ‘Money Lover’ b/w ‘So in Love’ – both songs were by Columbus and Russell. The A-side was an accomplished surf shuffle, the B-side a ballad, but the single went nowhere. So their next release was a cover of the instrumental ‘Ku Pow’ b/w ‘Autumn Leaves’, and its follow-up was Lennon and McCartney’s ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’.

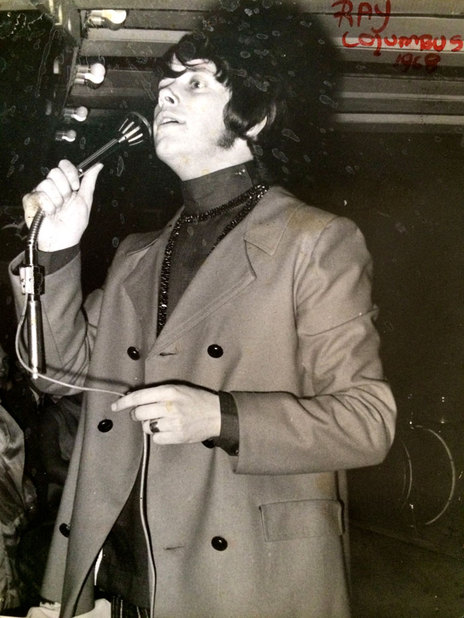

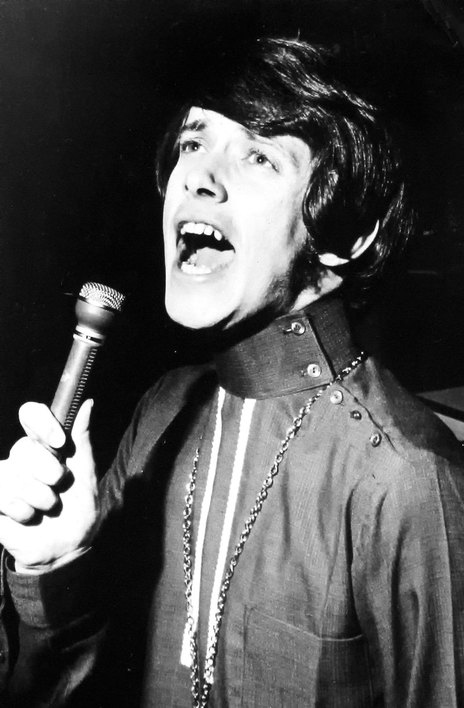

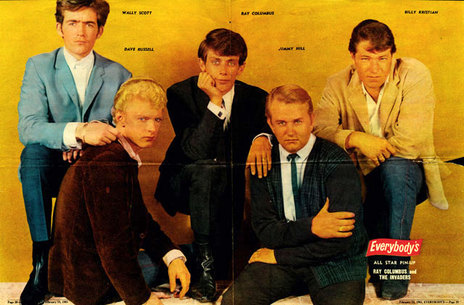

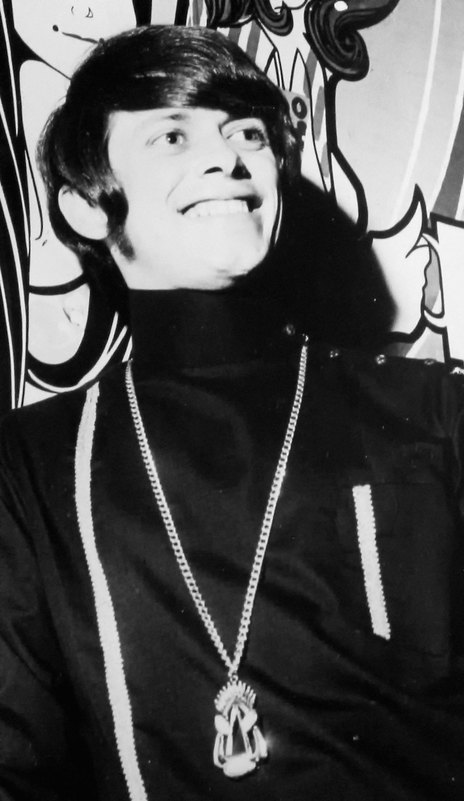

Late one night, listening to his short wave radio, Columbus heard ‘Ku Pow’ played on Sydney’s 2SM station. He was mortified to hear the DJ announce the group as a German surf group, “We have to get ourselves over there,” he said to Stebbing, who agreed. He decided to finance a tour in Australia, and in November 1963 the Invaders played at Surf City in Kings Cross: Sydney’s top teen dance venue. In the group were Russell, Kristian, Wally Scott on rhythm guitar, Jimmy Hill on drums, and Columbus on vocals. The dynamism of their act – and their stage suits: black satin for the band, red for Columbus – quickly made the group a rival for local acts such as Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs. Meanwhile, Columbus – showing a natural flair for promotion – bombarded DJs, TV producers and journalists with phone calls.

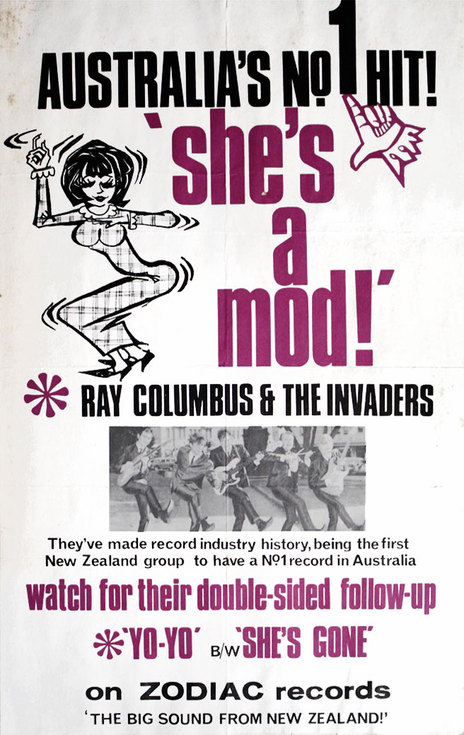

The Invaders returned to Auckland in February 1964 to record a cover of The Senators’ song, ‘She’s a Mod’. Initially, none of the Invaders liked it, although Columbus thought it had potential. The version they recorded was rockier than the British original, with a harder guitar sound and an exuberant “Yeah, yeah, yeah” hook that defined the times.

Released in June 1964, it didn’t attract much immediate interest in New Zealand, as the Beatles’ imminent tour left little room on pop-radio playlists. The Invaders returned to Sydney, where the song began to get airplay and then New Zealand programmers followed. The Invaders were featured on the TV pop programmes, Bandstand and Sing, Sing, Sing and got plenty of press; the Easybeats and Bee Gees emulated their sound and dress. ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’ got into the Australian Top 40, the first time a New Zealand recording charted in Australia. (The Invaders followed this up with a cover of the Beatles ‘I Saw Her Standing There’.)

By October, ‘She’s A Mod’ was on top of the charts on both sides of the Tasman, and the Invaders were the first New Zealand band to have an international No.1 hit.

In August, Columbus married Le’Vonne – an American citizen he met at the Shiralee in Auckland – and the next day he flew to Australia to promote ‘She’s a Mod’. This time the group’s reception was different. Australia was still basking in the sunshine of The Beatles tour and ‘She’s A Mod’ with its “Yeah, Yeah, Yeah” chorus was tailor-made for Australian radio, which was looking for anything and everything Beatlesque. Following an appearance at the 2UW Radio Theatre, Sydney went Mod crazy: the song sold 20,000 copies in two weeks then it began climbing the national charts.

By October, ‘She’s A Mod’ was on top of the charts on both sides of the Tasman, and the Invaders were the first New Zealand band to have an international No.1 hit. The song spent eight weeks at the top of the Australian charts, and a trademark dance – the Mod’s Nod – was created.

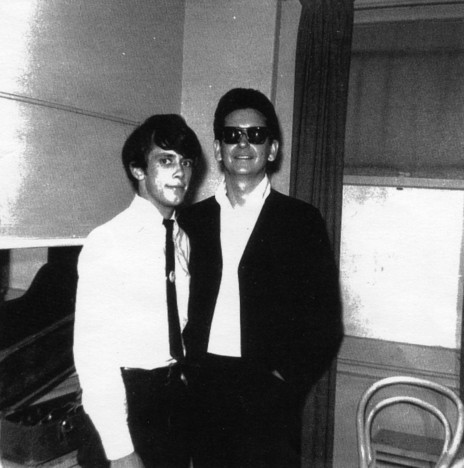

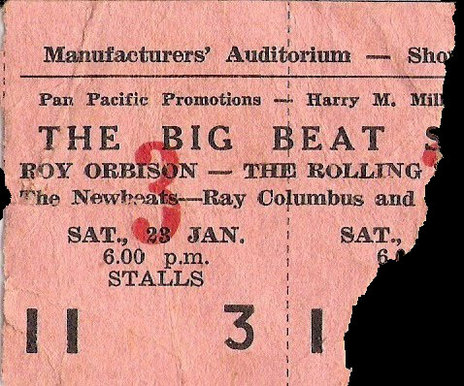

During the song’s rise on the charts, the Invaders were on their first Australian tour, Harry M Miller’s Starlift 64, with The Searchers, Del Shannon, Peter & Gordon, Eden Kane and Dinah Lee. The group was required to back the vocalists, and in the middle of the tour ‘She’s a Mod’ reached No.1. A tour with Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs quickly followed. The Invaders got stranded in Adelaide, and were sent tickets to Sydney by Miller. They joined his package tour Big Beat 65, which also starred the Rolling Stones, Roy Orbison and The Newbeats.

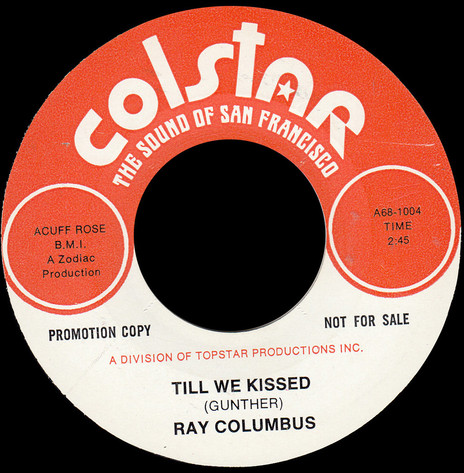

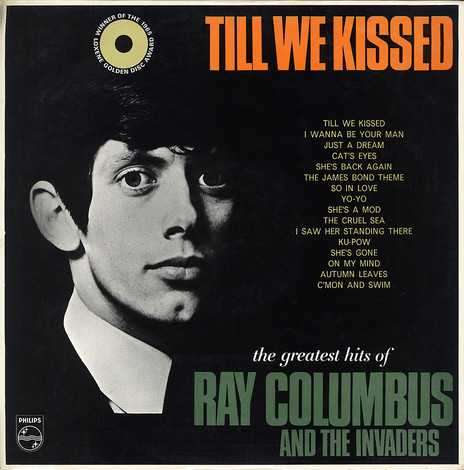

Also in 1965, Columbus and the Invaders recorded ‘Till We Kissed’, a Mann-Weil song originally called ‘Where Have You Been’ when it was released by Arthur Alexander. Columbus decided it should be a ballad: “The song had been covered by several groups but this was the first time that I had heard it and straight away I could see its potential,” he said. "With the Righteous Brothers being huge at the time I thought that the song was screaming out to be slowed down and given a Phil Spector-type production.”

‘Till We Kissed’ was recorded at Stebbing’s home-based studio with engineer John Hawkins. Mike Perjanik played piano and a six-piece violin section was overdubbed several times; two timpani were played from the family garage because they couldn’t fit through the studio door. Released in July 1965, it reached No.1 in New Zealand, and No.4 in Australia; along with Allison Durbin’s ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’ and OMC’s ‘How Bizarre’ it is one of the biggest selling New Zealand singles. It also entered the Cash Box and Billboard charts, the first Australasian record to do so.

In June 1965 the group again toured with the Dave Clark Five and Tommy Quickly but, despite their success, the Invaders’ breathless and ground-breaking roll was coming to an end. Columbus recalled, “The band had tried to get work visas to America after we had big hits in Australia and New Zealand, and they turned us down because the consular general said, ‘We need teachers and nurses, not musicians’. I knew I could get a green card but I didn’t want to go without the group. Billy and Jimmy decided to leave the band and join up with Max Merritt and the Meteors in Australia.”

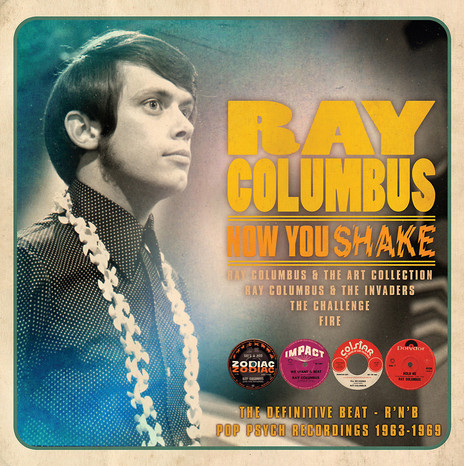

The group fractured during the recording of its second album, Original Numbers. This featured 11 original songs, including ‘Orbie Lee’, the bluesy ‘I’m Finding Out’, and a Booker T and the MGs-style instrumental, ‘90A Nashville Drive’. The album's perennial favourite was a garage stomper, ‘Now You Shake’.

‘Till We Kissed’ won the first Loxene Golden Disc Award in November 1965; on the same night Le’Vonne gave birth to a daughter, Danielle. The couple would later have a son, Sean.

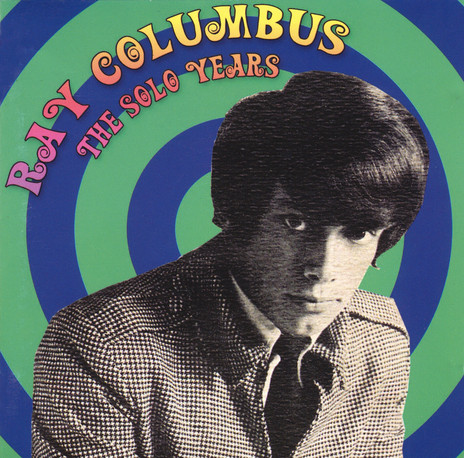

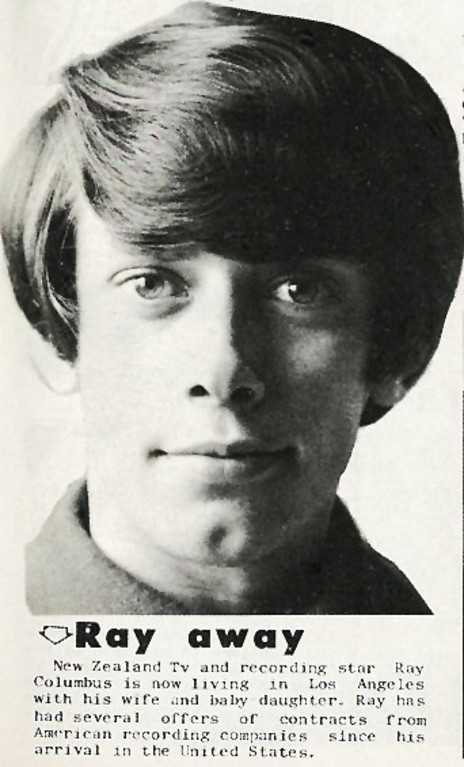

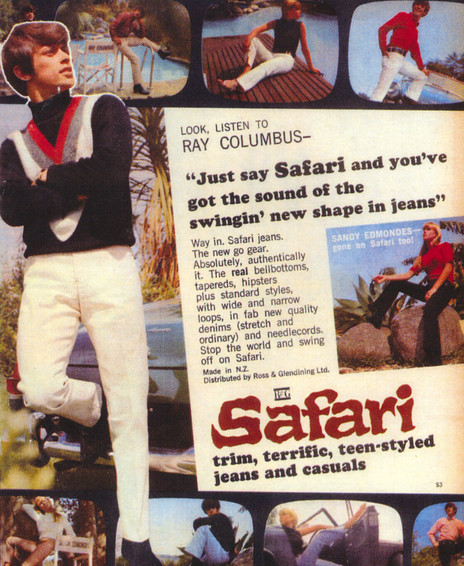

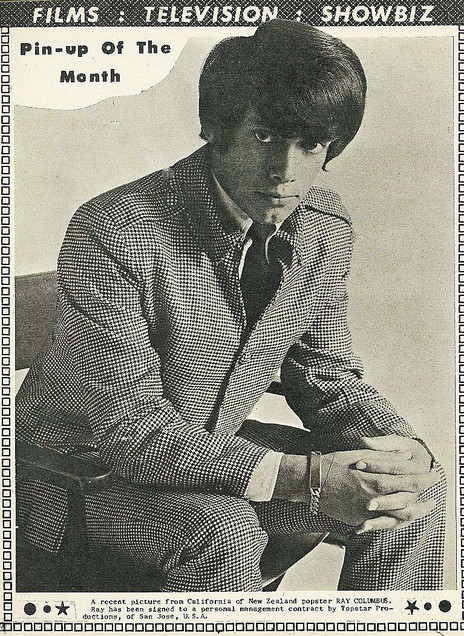

In 1966 Columbus toured New Zealand with Tom Jones and Herman’s Hermits, an Invaders’ greatest hits album was released on Zodiac, and The Ray Columbus Album on Benny Levin’s Impact label. Able to work in the US due to his wife’s citizenship, with his family he moved to San Francisco in July, signed a contract with Jim Ruder and secured representation by Al Zehner’s Topstar Management. Meanwhile, in New Zealand, Columbus’s song ‘I Need You’ won the APRA Silver Scroll for best composition.

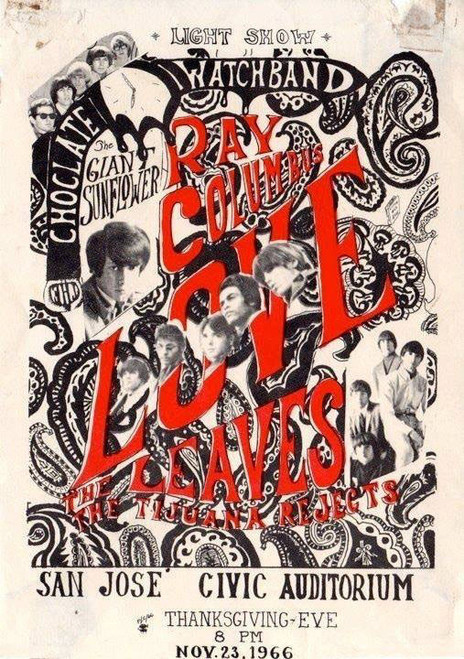

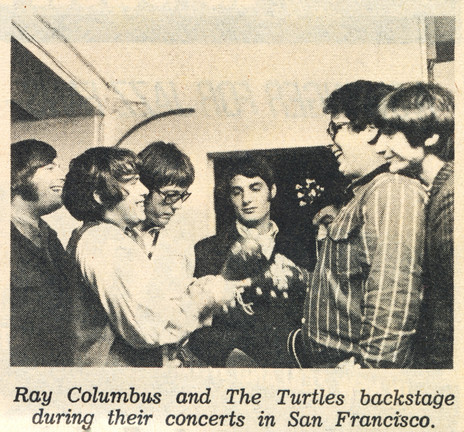

In San Francisco, Columbus recruited a band called the Art Collection and in 1967 they performed throughout California.

While in San Francisco, Columbus recruited a band called the Art Collection and in 1967 they performed throughout California. Released on Colstar, his first US single, ‘Kick Me’ got good airplay, but the band broke up soon after. Its follow-up was ‘I Would Rather Blow a Bagpipe’ (a possible reference to the Haight-Ashbury drug scene; Columbus was proud he never took drugs).

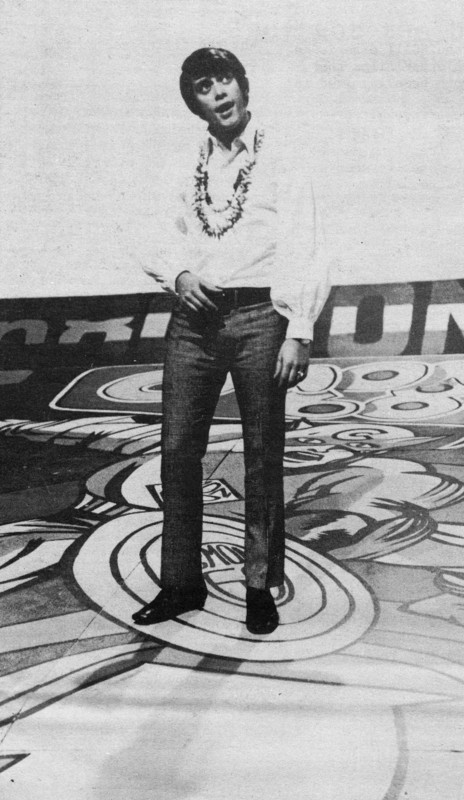

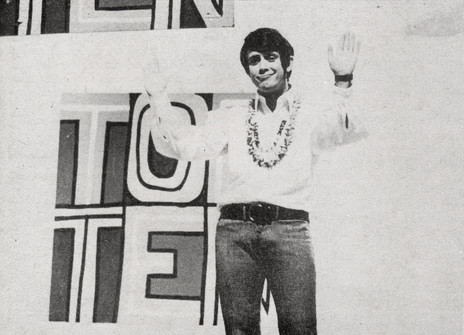

In 1968, he was invited by Phil Warren to return to New Zealand to join C’mon, the hit pop TV show that had recently lost its star, Mr Lee Grant. “Phil contacted me because Kevan Moore contacted him,” Columbus said in 2006. “Once Mr Lee Grant went to England, they asked if I’d come back for a season of C’mon. That’s all I came back for, six months, because things were really starting to happen for me in the San Francisco Bay Area. In fact I’d just been offered a TV show the day I left. That’s timing, these things happen. I was doing quite a lot there. But I thought it’d be nice to come home for six months and see everybody and show off our baby and all those sorts of things. Sixteen years later, my contract finished with television.

“It was amazing how things happen. Initially it was, maybe we’ll stay another year, then, oh next year she’ll be starting school and maybe we’ll start her here and see how it goes. Then my father-in-law died and we needed to take care of my mother-in-law. Things happened, life changes, and I do believe I was supposed to be here. I wasn’t supposed to go back, even though I’ve been back hundreds of times to promote New Zealand music. But I’ve never been back to live. Just circumstances, timing.”

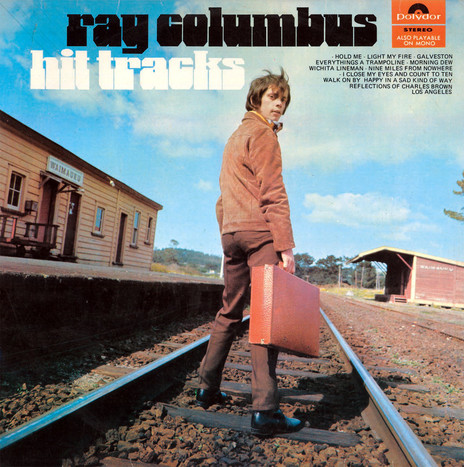

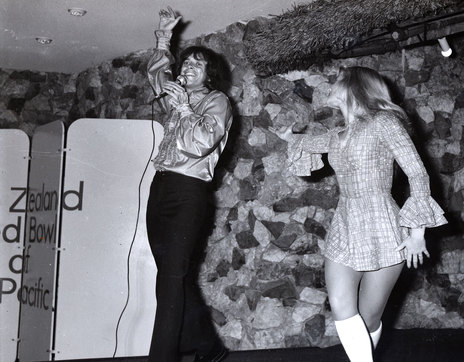

Columbus seemed ubiquitous in New Zealand entertainment from the moment he arrived home. In 1969, he appeared on another series of C’mon, hosted his own weekly radio show, and recorded a second solo album, Hit Tracks. Only four of the songs were by Columbus. “Polydor wanted an album of hit songs of the day,” he explained, “mostly ones that I had sung on C’mon 68, even though I had a suitcase full of songs. But I was miles too busy to argue the point so I just went with the flow.”

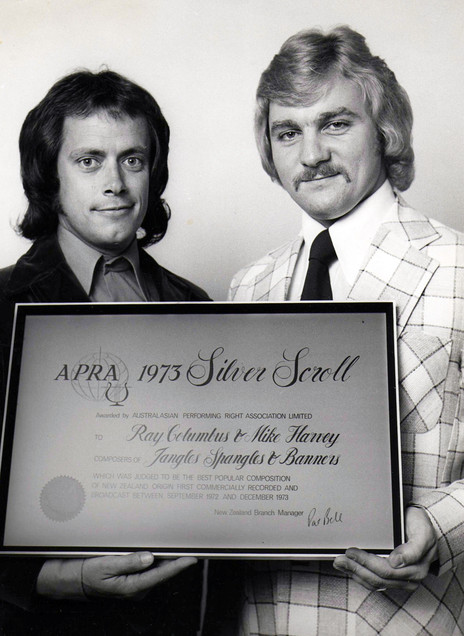

He continued to write songs – using what he described as the “claw method” of shaping chords on a piano – and was often a finalist in the Silver Scroll, with songs such as ‘Happy in a Sad Kind of Way’ (written in San Francisco, thinking of home), ‘Los Angeles (Is Where I Want To Stay)’ and ‘Travelling Singing Man’, a song he was always proud of. Radio especially got behind ‘People Are People’ (written with Shade Smith of The Rumour) and ‘Jangles, Spangles & Banners’ (written with Mike Harvey, and a second Scroll winner). The following year, Columbus was one of several artists to perform for Prince Charles and Princess Anne at Super Pop 70, a royal variety show produced by Max Cryer.

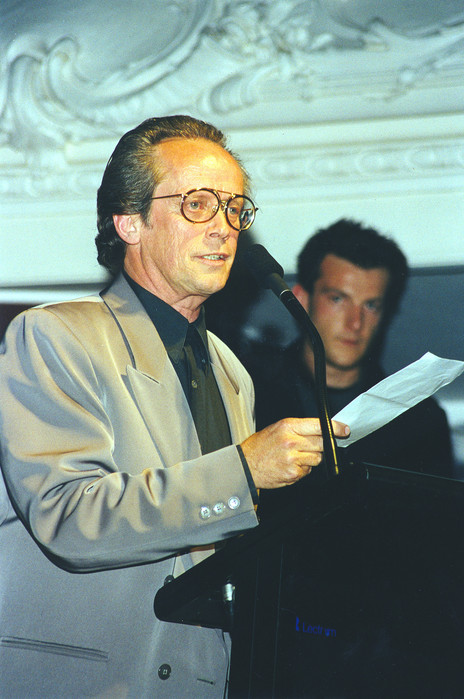

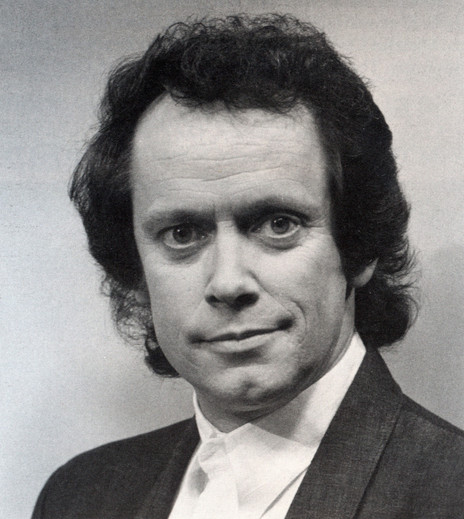

The 1970s saw Columbus become a stalwart of New Zealand entertainment, championing artists as a manager, producer, television host and NZ Listener columnist.

The 1970s saw Columbus become a stalwart of New Zealand entertainment, championing artists as a manager, producer, television host and NZ Listener columnist. Working for Phil Warren’s Fuller agency, he was pivotal to the success of acts such as The Chicks, Shane and The Rumour. He won a Benny award from the Variety Artists’ Club and was awarded an OBE for services to music in 1974. For a decade he was a member of the APRA music committee, supporting local songwriters and composers, before becoming a “writer-director” on the board from 1980 to 1992.

Television shows in which he was prominent as a performer, host or judge include A Girl to Watch Music By, My Name Is Ray Columbus, New Faces, and That’s Country. As a member of the QEII Arts Council from 1975 to 1983, he was branded “Mr Quota” as he pushed for more local music on radio and television. Behind the scenes on the Arts Council, his most astute decision was possibly the moment in 1976 when, with chairman Hamish Keith, he arranged an emergency grant of $5,000 for Split Enz when they were stranded in London. His role in the music quotas campaign backfired when, in the same year, many New Zealand radio stations refused to play his RCA single, ‘I Wanna Be the Singer’.

Recording after the 1970s was sporadic, but he did revisit his biggest hits several times. He re-recorded ‘She’s A Mod’ at least twice (in 1988 it was with Double J and Twice the T, and titled ‘She’s a Mod/Mod Rap’), released a new version of ‘Till We Kissed’ on Pagan in 1987, and also guested on a version by Herbs.

Outside of music, Columbus was heavily involved in community organisations, serving on the board of the Sir Robert Kerridge Foundation, working for the Foundation for Alcohol and Drug Education in the late 1980s and helping to organise the nationwide Ride Against Drugs in 1993. He was presented with a 1990 Commemorative Medal for his contribution to the 150th anniversary of New Zealand. Columbus married his second wife Linda in 1992 and adopted her daughter, Tina. Together they moved to Matakana to manage an events and function centre.

In 1997 Columbus successfully sued the Truth newspaper for claiming he received $70,000 for organising 45 minutes of entertainment for the Auckland Rugby Union during a test match between the All Blacks and the Springboks at Eden Park. He was actually paid $5,000 from a $70,000 budget, around 15 percent.

More recently, he endured many health setbacks. In 2002 Columbus and his wife were involved in a major car accident in the US; two years later he suffered a heart attack 10 days before a local body election in which he was standing for the Rodney District Council; strokes in 2004 and 2008 caused some paralysis.

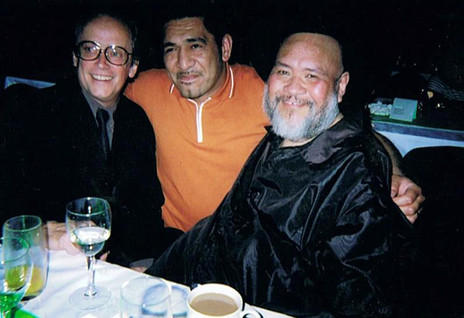

But the music continued: in 2002 he toured Australia with the hugely successful nostalgia show Long Way To the Top (alongside Billy Thorpe, Dinah Lee and many other stars), and two years later helped organise a one-off New Zealand version in Rotorua, featuring Sir Howard Morrison, Allison Durbin and John Rowles. This led to the 2006 New Zealand Best of the Best tour, with Johnny Devlin, Shane, Larry Morris, Sharon O’Neill and Tom Sharplin. “I said, as long as it’s not called Give It A Whirl [a TVNZ rock history series]. If so, I’m not doing it. My father would turn over in his grave if he thought that I was doing a show that was called Give It A Whirl. He didn’t put me on stage to give it a whirl. I was to be an entertainer. We weren’t just giving it a whirl, it was serious stuff.”

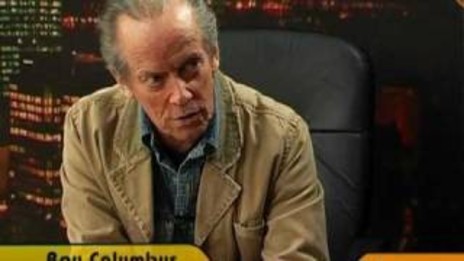

In a field of creativity often regarded with disdain, Columbus earned respect for his artistry, his showmanship, his dedication and generosity. With the Invaders, in 2009 he was appropriately one of the first inductees into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame: for 50 years, he helped create the local music industry. On 29 November 2016, the day Columbus died, the Ministry of Education announced that songwriting would become part of the high school curriculum. While others were involved in the political lobbying, they would acknowledge the development was unthinkable without the groundwork of Ray Columbus.

--

Sources: interviews by Michael Colonna, Chris Bourke, Grant Gillanders and Kate Preece; Ray Columbus: The Modfather – the Life and Times of a Rock’n’Roll Pioneer, by Ray Columbus and Margie Thomson (Penguin, 2011).

--

Read Ray Columbus and The Invaders here

Read Ray Columbus and The Rolling Stones here

Read Columbus Invades America here

Read The Mod's Nod here

Read Ray Columbus on 1950s Christchurch here