C’mon - watch the complete, remaining Series One episode, 1967

After the introduction of television in New Zealand in 1960, homegrown music and light-entertainment shows all shared a common problem. There were no purpose-built television studios in the country. Clever use of angles and lots of mid and closeup shots only got you so far. In early 1966 the Shortland Street television studio came into commission and immediately Kevan Moore envisaged a new show for the changing times. He was already a veteran-music show producer, having produced In the Groove (1962), Let’s Go (1964) and On the Beat Side (1965).

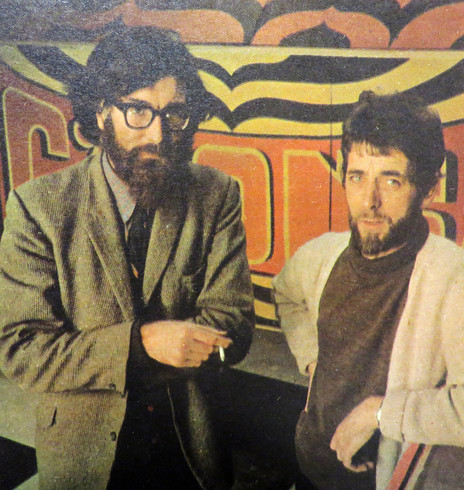

Kevan Moore, producer of C'mon, with his star host, Peter Sinclair

C’mon – an overview by Kevan Moore

It was a dark and stormy night in downtown Wellington. Apart from me, the offices of WNTV1 were deserted. I was thinking about a television show, a pop show, something along the lines of Hullabaloo (the American show) reflecting the swinging sixties: Op and Pop art, clean white studio, multilevel ramps and risers, Go Go dancers, frenetic pace. I listened to disc after disc, nothing appealed until the pounding sound of Freddie Cannon’s ‘Come On, Come On’ shattered the silence: I had the title and the theme. It also carried the imperative of action TV and movies – “C’mon let’s go”. It further linked in with a previous pop show of mine, Let’s Go!.

This show could be done in the new studio in Auckland; nowhere as big as the TEN10 Sydney studio I worked in the previous year, but it would do. Peter Sinclair would again be the frontman, always a reliable performer and able to carry on regardless when things turned to custard.

Given the green light to produce a pilot, I contacted my old friend Phillip Warren to audition some artists and eventually selected relatively unknown artists on the New Zealand television scene: Mr Lee Grant and Sandy Edmonds. To get our initial audience and to give it power, we needed a powerful established star. I called in a favour and Howard Morrison agreed to star. “Pop a go-go” dancing, being a new style of dancing to this country, there was only one choreographer capable of recruiting and training our dancers: Dorothea Zaymes, ex-Royal Ballet. Jimmie Sloggett became the musical director and we recorded the soundtrack at Bruce Barton’s Mascot Studio.

Visual effects, staging, graphics, costumes and lighting played a vital role; it required finding adventurous souls such as Tony Stones, designer; Peter Gossage, graphics; and Ian Ingley, lighting. To achieve the fast pace I required camera-cutting at a speed never attempted before; also, when required during moody numbers, dissolves with sensitivity. This task was too demanding for the trained vision mixers so I selected 17-year-old Janice Wharekawa who, thrown in at the deep end, swam into a brilliant career. Even though the C’mon pilot was recorded, we shot it as live, warts and all.

--

C’mon goes to air

The much-anticipated pilot for the local pop show C’mon burst onto our screens on 26 November 1966, with the emphasis on “burst”. It featured Mr. Lee Grant, Sandy Edmonds, Herma Keil and The Keil Isles, Larry’s Rebels, Howard Morrison and The Chicks.

The pilot started with Morrison singing the theme song from his movie Don’t Let It Get You, which had been released in August. Edmonds changed direction and sang her fuzz-guitar-drenched new single ‘Come See Me’, which segued into Larry’s Rebels performing their brand new single ‘I Feel Good’ and the Beatles song ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’.

The set of C'mon in 1967. Hugh Lynn is standing on the right.

Next up was Mr Lee Grant who sang the current Los Bravos track ‘I Don’t Care’ while being mobbed on screen by some of the 100 invited female studio guests under Moore’s instructions; this had him rubbing his hands in glee at the thought of extra publicity for the show (as if it needed it).

The Chicks brought some normality into the proceedings with their version of the Lovin’ Spoonful song ‘Rain On The Roof’. A six-minute Gene Pitney montage featuring all artists brought the first half to an end.

After a few words from the sponsors it was back into another frenetic and frantic 13 minutes of pounding the sound (a catch-cry of Peter Sinclair’s), culminating in Morrison and the cast closing with ‘Land of 1,000 Dances’. (Yes you read that properly: Howard Morrison singing ‘Land Of 1,000 Dances’).

Even before the end of the credits, it was plain to see that the pilot was a complete success and its continuation would be assured.

Auckland Star television reviewer Barry Shaw – who described himself as a middle-aged square – led the avalanche of rave reviews from press and public alike.

“No, Shindig was never like this. Nor was Hullabaloo. Both American imports were out-shook and out-hollered on Saturday night by C’mon. Undoubtedly the loudest, fastest-and best-pop show to hit the New Zealand television screen. In fact, it is almost impossible to believe that dear old auntie NZBC spawned this pulsating trendsetter. A show so far ahead that I could hardly believe my eyes or trust my ears.”

Anthony Stones (left), set designer of C'mon and the father of Dominic of the 3Ds, later became an internationally renowned sculptor.

Shaw went on to praise the performers and gave special mention to Howard Morrison’s exciting performances before ending his review with his appraisals of front man Peter Sinclair, the dancers and Anthony Stones’ set designs. “I couldn’t keep up with Peter Sinclair. But, being a square, I don’t suppose I would have understood what he said even if I could absorb it. But he was very definitely the right sort of guy to be pressing the accelerator pedal. The industry and energy of Dorothea Zaymes’ go-go motion girls made their equivalents in Hullabaloo look like scruffy moppets. To AKTV2’s Anthony Stones must go a 1967 NZBC Emmy for his best set ever, a pop-art background that was simplicity itself but exactly right. Those whirls and squares, the chequered costumes, the crocheted gear of the go-go motion girls showed, too, a keen appreciation of visual effect, which was heightened by effective lighting.”

Shaw was so insistent that the show be given the green light for a full series in the new year that he concluded: “If the show doesn’t get the chance to continue next year, then there ought to be questions raised in Parliament.”

Watch the Gremlins performing 'Blast Off 1970' on C'mon, 1967

For all of the excitement and action on screen, the pilot didn’t come without hitches. Moore kept a firm hand on proceedings and took no prisoners. This was his show and vision and anyone meddling with mediocrity or not pulling their weight would wear his wrath. After all, it was his impeccable reputation on the line just as much as the cast and crew. During the final afternoon dress rehearsal, two of the stars were sent packing, in tears, and told in no uncertain terms by Moore to come back in three hours and produce the goods – or they were out. They came back and produced the goods. With a large contingent of production staff and a complex artist roster, Moore ran a tight ship. He had to, as each week’s episode was a seven-day exercise, and any setback could be disastrous.

Dancer Barbara Dean recalls an early altercation with Moore: “A few of the dancers went to lunch at a nearby Chinese restaurant during one of the rehearsal days. We were no more than a minute or two late back and Kevan ripped us to shreds. Point taken ... and in the intervening 50 years I don’t think that I have ever been late for anything.”

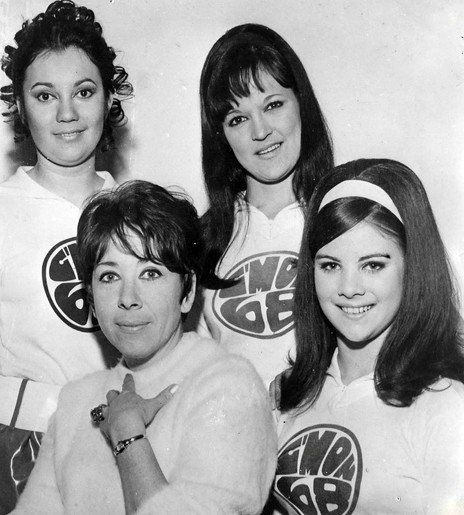

The Chicks on a C'mon op-art set designed by Tony Stones

Several eagle-eyed viewers wrote to newspapers asking about the strange man frantically running across the screen behind Peter Sinclair after the final number of Larry’s Rebels. Morris reveals, “During our last number the rest of the band were positioned around the set with me on the ramp. In my enthusiasm I decided to do a grand finale and in the spur of the moment I leaped up into the air as the song finished, which always looks good. I severely underestimated the steepness and width of the ramp and when I came down I fell off the edge and landed smack on top of the slide projectionist whose job it was to project images on to the wall behind the stage. I was briefly stunned and my initial reaction was ‘Shit!! I’ve killed the poor bastard … a second later he snorted, shook his head and carried on projecting, thank Christ.”

Seeing his main star vanish off the side of the stage, Rebels’ manager Russell Clark darted across the stage as the camera cut to Sinclair. Such was the hectic pace of the show only a few viewers seemed to notice the mayhem.

The 26-week series was given a healthy budget of $40,000. Phil Warren set up James Productions primarily as a recording entity to record the show’s regular artists; these recordings were distributed by Festival Records.

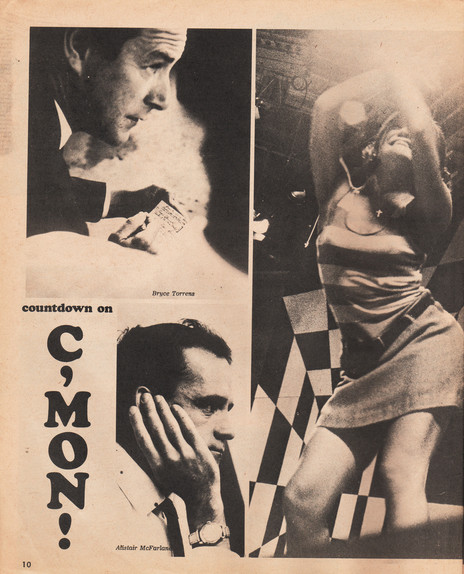

Playdate magazine lauded the show over several pages, with photos by Roger Donaldson

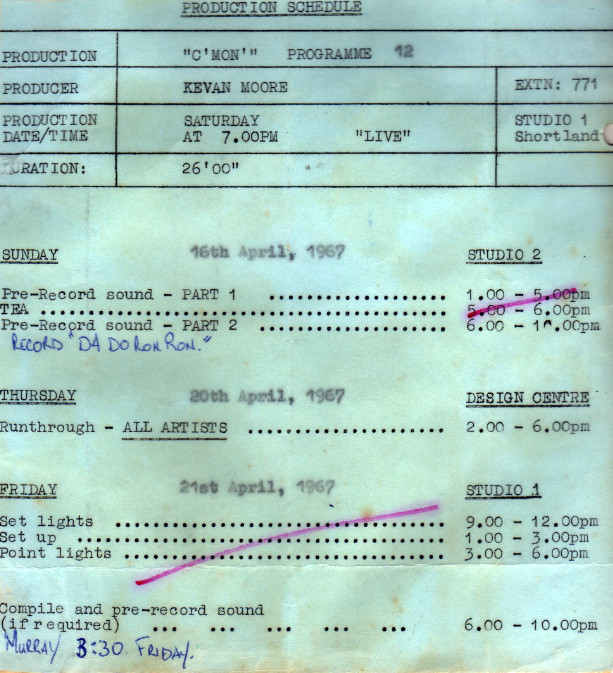

Working on C’mon either as a resident performer, go-go dancer or on the technical side was not a one-day-a-week job. Weekly staff timetable sheets from the time reveal an arduous workload for all. On Sundays, they recorded the audio tracks for the following Saturday’s show. Monday afternoons the musical director instructed the band and vocalists on the songs chosen for the following week’s show. The dancers rehearsed Tuesday and Wednesday. On Thursdays, a full rehearsal run through, before the artists assembled the new set that they had been working on all week. Ten hours on a Friday were set aside for the lighting set-up and run through. Saturday was the big day with a 10.30am start and up to four run-throughs. Late afternoon there was a full dress rehearsal, then a 15-minute tea break. The show was screened live to the Auckland AKTV2 area and videotapes were sent to the other three main centres for viewing a week later: Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin.

A month before the series launched, talks were initiated between the NZBC and the ABC for the Australian channel to purchase the series. This development saw Phil Warren, who was in charge of booking acts for the series, tentatively book Australian stars Johnny Young, Ronnie Burns, Normie Rowe and Ja-Ar (aka John Rowles), which would potentially boost the show’s saleability. Former Auckland agent Graham Dent – now based in Australia representing many of their biggest names – made a special trip over to finalise plans, which was going to start with Johnny Young appearing in the fourth week. For a variety of reasons, mostly financial, none of the Australian artists appeared while negotiations remained ongoing with the ABC for the time being.

The eagerly anticipated first series of C’mon started on 4 February 1967 at 7pm; it was preceded by Thunderbirds and followed by the 7.30pm News. On the same day, it was reported that New Zealand now had 500,000 licensed television sets (in a population of 2.7m).

For the first episode the resident artists were Mr Lee Grant, Herma Keil and The Keil Isles, and Sandy Edmonds (who came in for special praise with her performance of ‘Mellow Yellow’). They were joined by guest artists Lew Pryme, Christine Barnett and The Gremlins, whose latest record ‘Understand Our Age’ was then charting nationally. Moore’s dream team of background and technical staff was retained from the pilot including choreographer Dorothea Zaymes who brought a wealth of experience gained from 20 years with the Royal Ballet Company in the UK.

Watch Herma Keil sing 'Music To Watch Girls By', C'mon, 1967

Needing to push the boundaries for his show, Moore approached Zaymes to become the show’s choreographer. Zaymes, who was affectionately called Dolly, accepted and immediately put aside all classical ballet thoughts of swans and nymphs living underwater. She then created the C’mon go-go girls. Trish Hodson, Jill Lewington, Christine Bradcock, Jill Lewington, Christeen Shaw, Diane Dower, and Anita Marr started the first series as regulars. Because of a high attrition rate, other dancers were added throughout the series, including 16-year old model and dancer Barbara Dean – who would go on to dance in the next two series – and 15 year-old schoolgirl Trudy Klink. Champion ballroom dancer and future promoter Hugh Lynn made several appearances during the first season, whenever a male dancer was deemed necessary, such as a 1950s rock’n’roll tribute on the May 6th show. The existing footage that remains from C’mon gives a brief insight into the creativity of Zaymes and her dancers: there are numerous well-executed routines that are obviously very difficult but made to look so easy. To all viewers, trained or untrained, this team was no mere eye candy that just stood there and shook, like some of the overseas shows. By comparison, this was poetry in motion.

Choreographer Dorothea Zaymes with three C'mon dancers from the 1968 series (from left): Vicki Nelson, Chris Bradcock, Barbara Dean

With Herma Keil being one of the show’s regulars it made sense to include his backing band the Keil Isles as the show’s resident band. At the time, the Keil Isles were Brian Henderson (keyboards and vocals), Billy Kristian aka Karaitiana (bass and vocals), Jimmy Hill (drums and vocals) and Roger Skinner (guitar and vocals): all seasoned musicians. jazz player Murray Tanner (trumpet) and the show’s musical director Jimmie Sloggett (saxophone) rounded out the backing band.

Another vital ingredient in the series was the set designer, English-born Anthony Stones, who led a small group of talented artists and designers. His philosophy for designing sets was simple: “Although the show is seen on-screen in black and white, I like to use an array of bright colours which puts the artists in the right mood to give a good performance. I like to work in a mixture of op art and art nouveau.” (Stones would later become an internationally acclaimed sculptor, especially of statues; his son Dominic was in The 3Ds in the 1990s).

The first episode, like the pilot, received lavish praise from TV critics and the public alike. The bags of letters sent to the country’s newspapers were a testament to that. Guest artists for the first month included The La De Da’s, Larry’s Rebels, The Dallas Four, Ray Woolf and pop/folk trio The Newfolk, whose latest record had just been released in the UK on the Decca label.

One point noted after the first show was the go-go dancers’ legs looked ungainly under lights, which was attributed to them wearing unflattering white stockings. This was quickly remedied by the wearing of black tights for the following episodes.

After the third episode (18 February 1967) the excitement and managed chaos of a typical Saturday afternoon on the C’mon set was succinctly captured by an unnamed reporter from the newly launched and short-lived newspaper Auckland Life. Numerous people involved in the first series were interviewed for this article; when asked to describe a typical episode, they all went blank and revealed that nerves and a tight schedule had left them unable to recall much. So the fly-on-the-wall article provides an invaluable insight:

“I said goodbye to the warm summer sunlight and plunged myself into the maze of stairs and corridors of the Shortland Street television studios. Peter Sinclair was sitting in the corner quietly mumbling his script to himself. Go-go girls in gaily striped poor-boy dresses were having a last-minute run through of routines after a week of solid rehearsals, technicians with individually printed T-shirts (“we have to have them, or we wouldn’t recognise each other in the crush”) rushed in and out manoeuvring cameras, while makeup artists, dressers, pop stars, managers and friends leapt out of their way.

Watch Mr Lee Grant perform 'Get Me To The World On Time', C'mon, 1967

“There was resident pop vocalist Sandy Edmonds touching up her makeup; singer Lee Grant exuberantly waving round a letter which had just been delivered to him. Herma Keil was perched on a stool, looking rather tired; the show had been rehearsing in top gear since early that morning, with only a short break for lunch. Larry’s Rebels were tuning up their instruments. Eliza Keil (Herma’s sister) was searching for a sticking plaster for a cut finger, while Howard Morrison wandered unperturbed through the middle of it all.

“And everywhere, an impression of vivid colour. Set designer Anthony Stones’s use of pop-art themes in hot orange, pinks and yellows created a really swinging atmosphere. And coupled with the gaily coloured costumes of the performers, the effect was electrifying, If only these colours could be seen on screen. Then in trooped the C’mon audience in switched-on gear rivalling that of the stars. The tension mounted, ‘Everyone on the set! Five minutes to go!’ As the clock hands sped round, compere Peter Sinclair took up his position and the first act stood ready. The red light flashed, the cameras hummed – and C’mon! burst onto the screen in thousands of eagerly waiting homes. And to see the relaxed smiling faces of the performers, you’d never guess at the frantic activity that had been going on around them.”

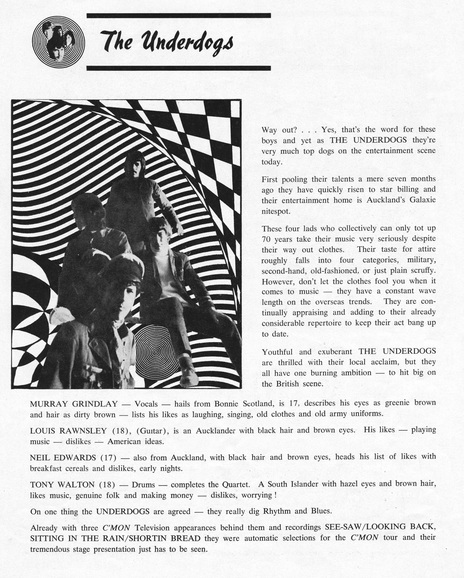

The Underdogs in the 1967 C'mon tour programme - Murray Cammick Collection

An unlikely relationship of mutual respect began at the beginning of the second month when Auckland blues group The Underdogs were invited onto the show as guest artists. The Underdogs were notorious for taking practical jokes to grandiose heights with no one immune from their dastardly deeds, which was in direct contrast to Moore’s strict regime. Moore revealed years later that he enjoyed their schoolboy antics, but more importantly their musicianship – and the fact that the cameras loved them.

Murray Grindlay of The Underdogs recalls: “Moore absolutely adored us. Every time that we appeared on C’mon the switchboards would light up with complaints, and Kevin would go YEESS!!! He relished the publicity. We appeared on C’mon on numerous occasions wearing our German military and fireman uniforms. The fire chief would ring and say for god’s sake you can’t do that, and half of the RSA would ring through and quite rightly give us a bit of a serve about how they fought and died for long-haired weirdos like us.”

Watch Herma Keil and Billy Karaitiana sing Sam & Dave's 'I Take What I Want', C'mon, 1967

Obviously, alcohol was a no-no on set, but one group who pushed the limits was Auckland soul group The Action. Their lead singer Evan Silva confesses, “We used to have to go into the television studio on a Saturday morning and stay there all day recording and rehearsing and hanging around until broadcast time. We became pretty bored with the waiting around. We couldn’t choose the songs that we wanted to do and by the end of the day, we’d be strung out on lemon gin that we had snuck in (it was the cheapest grog that you could get at the time). We’d do our best to stand up and perform and after the cameras stopped, go and do a gig at the Galaxie that night. People would have just seen the show on TV and just pour in. It’d be full, and we would play and lift the roof off.”

End credits