In NZ rock history book Stranded In Paradise, John Dix calls Bunny Walters “a great vocalist who's never been truly appreciated", describing his voice as having "more grit and colour than most of his contemporaries, which not even his sometimes banal choice of material could conceal.”

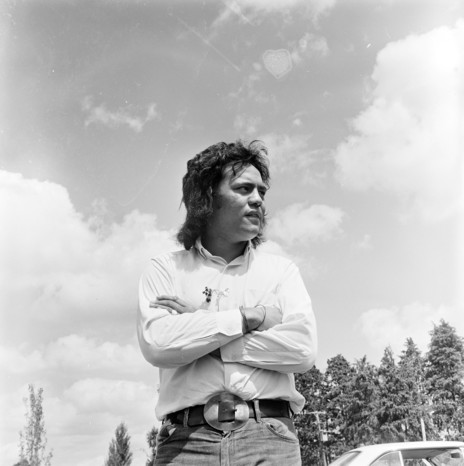

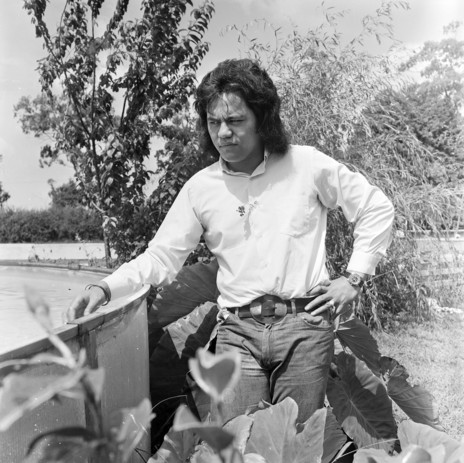

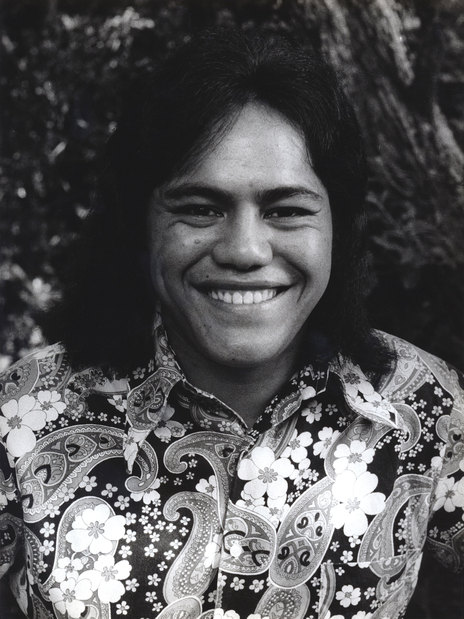

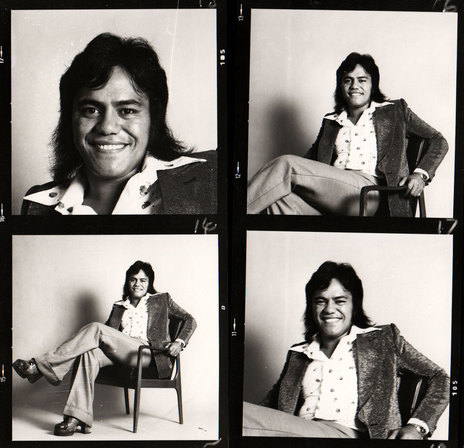

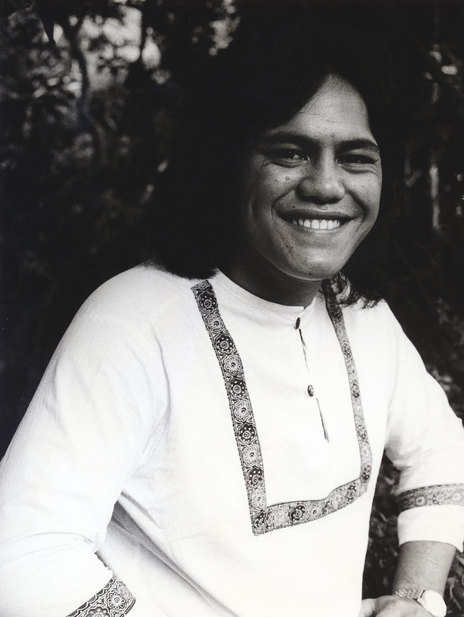

Born and raised by his mother Manawakore Jacobs and his father Tipewhenua (Tipene) Walters near Katikati on the east coast of the North Island, Miha “Bunny” Walters was one of New Zealand’s most prominent performers during the 1970s, with chart success and a constant profile on TV pop and variety shows.

“You could never out-sing him. I believe he was one of our greatest male singers.”

– Tom Sharplin

Rock and roller Tom Sharplin told Trevor Reekie for NZ Musician magazine (Feb/March 2008 issue): “I first met Bunny at an after match rugby party in Katikati, my brother’s team had played Bunny’s brother’s team. Bunny was about 14. Singing along around the piano, I remember thinking, ‘Who is that guy trying to out-sing me at the other end of the piano?’ When I told Bunny he said he was thinking the same thing. I toured around the country many times with Bunny … You could never out sing him. I believe he was one of our greatest male singers, he pushed you to do your best all the time.”

On the Te Rereatukahia marae where Bunny grew up, music was a big part of his upbringing. “Just hanging around, listening to the music, picking up what they were doing,” he told TV documentary Unsung Heroes of Māori Music in 2013, “how they played guitar, how they sang, all the harmonies involved in their singing, it was neat.”

“The music thing sort of happened at school,” Bunny explained. “I realised that I had a reasonable voice. So did people around me, they’d say ‘Bunny, you can sing, boy’. My brother [Abe Walters] used to do a duet, with him on guitar. He’d let me sing with them. That’s how my confidence was built up.”

Bunny sang what he had heard at parties around their settlement, songs by The Drifters and Tom Jones, the latter of which was his main inspiration and the biggest influence on his singing style. “I didn’t learn about the funkier stuff until I started living in the city and hanging out with other musicians,” he told AudioCulture.

His professional career kicked off early, with help from older brother Abe, who was already a professional performer. “We were playing in Rotorua and Bunny came over,” Abe Walters told Unsung Heroes. “How old are you now Bunny? 14? Oh you’re a bit too young to be in the band. Then he says ‘Oh no I’m 15 that’s right’ and we said ‘Ok Bunny, you’re with us.’ ”

With his two brothers on guitar and Bunny on bass, the siblings shared one microphone, which also went through the bass amp. It wasn’t long before his talent was spotted.

“I said ‘Haere ra’ to all the whānau and caught a bus to Auckland.”

— Bunny Walters

“One night these two Pākehā fellas down in the audience were looking at me. They called me over during the break and said, ‘We’d like you to come up to Auckland.

“They were a couple of building contractors ... they had a big cabaret coming up,” Bunny told AudioCulture, “and they asked ‘would you like to sing at it?’ That’s how it started. I sang at Trillo’s. Terry Gray was the leader of the band, he was a prominent music arranger in New Zealand history.”

“They said ‘we’ll take you to see all these different agents,’ but it was just the one, Eddie Hegan, Hegan Entertainment. They didn’t say sign here, they congratulated me and the others and that was it.”

Bunny returned to Rotorua, and the two contacted him. “They said, ‘We’d like to be your managers. Would you like to come up to Auckland, we’ll look after you?’ I said yes yes yes. So I did, I told my family I was off to the big smoke to become a pop star and that was it. I said ‘Haere ra’ to all the whānau and caught a bus to Auckland.”

So at the tender age of 15, Bunny Walters shifted to Auckland, straight into the YMCA. “They booked me straight into the YMCA, paid my rent, three meals a day, it was great. But they didn’t have a clue.”

Signing with Impact

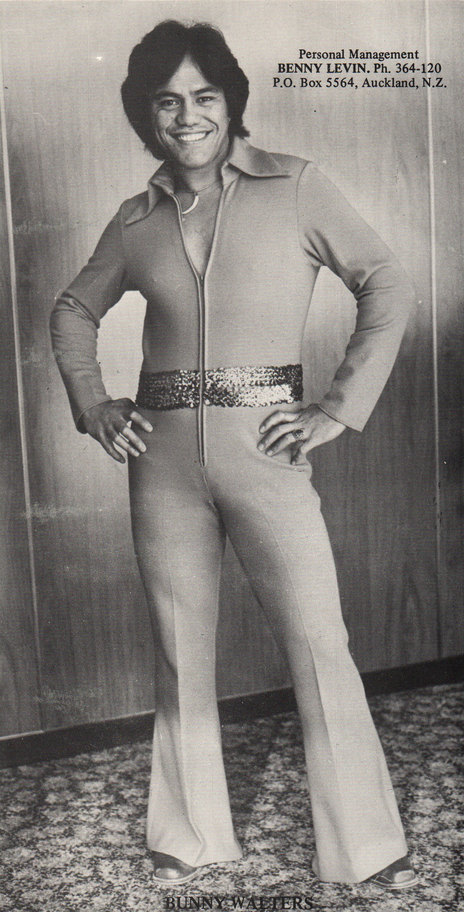

One weekend Bunny returned home and went to a social. The bandleader (from the Ricky Devon Set) gave Bunny a number for promoter Benny Levin, one of NZ’s premier entertainment promoters of the time. “He said he’s having auditions up there soon, see if you can get an audition with him. I went back to Auckland, rang the number, they said ‘we’re sorry, we’re full up, there’s no more room.’ So I just persisted … they said ‘ok, we’ll fit you in.’”

Bunny was given an address in Herne Bay to go to, he rang a taxi company and asked how much to get there. “They said sixty cents. I had a dollar. I get there and there’s a queue. I joined the queue and then there were more people behind me. I sang ‘I Can’t Stop Loving You’ and Benny said, ‘That’s it, auditions are over. We found our man.’ They sent everybody else home. The next day I went and signed the contract.”

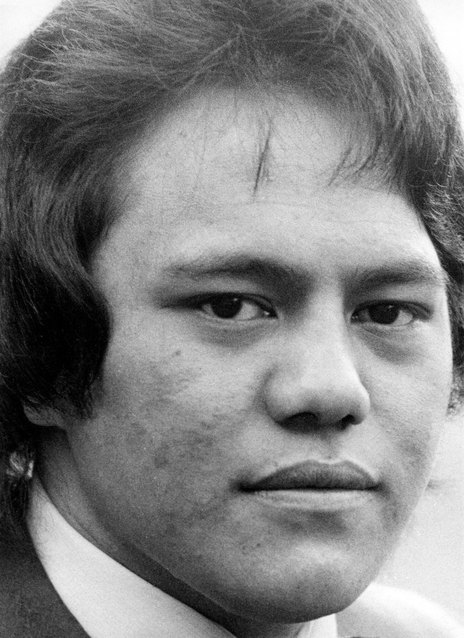

Levin and Clark described his voice as “nothing short of incredible.”

Bunny Walters became one of the main artists on Benny Levin and Russell Clark’s Impact Talent Associates Ltd roster and Impact record label. Levin and Clark described his voice as “nothing short of incredible” to the Auckland Star (April 8, 1970), which reported that the pair were about to showcase him at a large conference for over 1200 international hoteliers and talent seekers, to be held in Auckland that year. Success was assured if he could impress.

As with others on the label, which was also home to Larry’s Rebels, he was groomed for stardom. Bunny entered himself in big talent quests, and worked his way towards the final of Joe Brown’s Search for Stars, on January 12, 1970, in Rotorua. As part of the prize the winner was to sign an artist contract with Joe Brown, but Bunny was already contracted to Benny Levin. As second place winner he received $500 while Joe Brown signed the winner and two others.

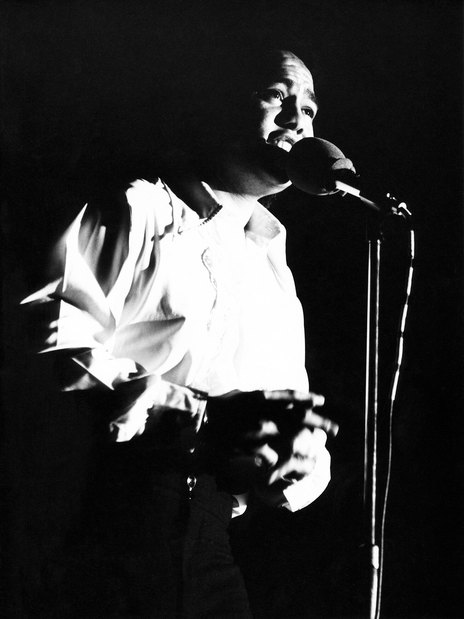

Footage still exists of 16-year-old Bunny Walters performing a remarkably confident version of ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’ at the Search for Stars final. “I don’t know what inspired that in me, probably Tom Jones,” he told AudioCulture. “He was such an inspiration for me back in those days. I just wanted to copy everything he did.”

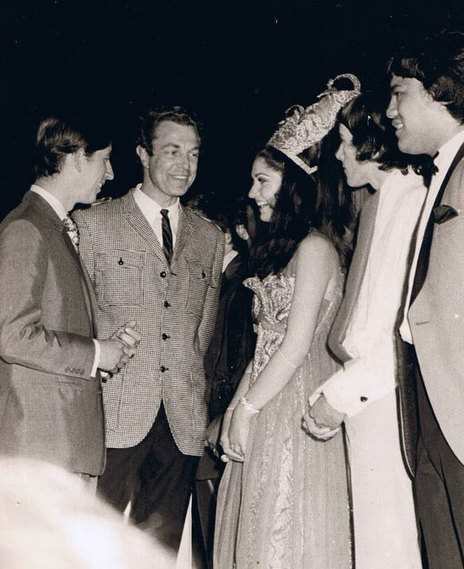

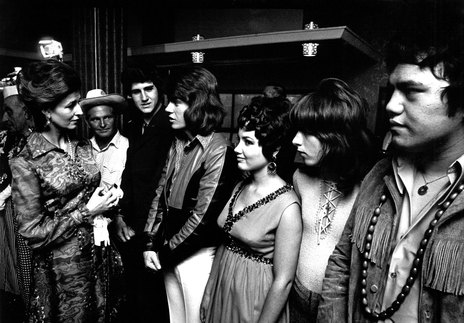

Bunny also performed in a showcase in front of producers Kevan Moore and John Barningham, and Max Cryer, who was producing Superpop 70, an outdoor pop show organised for a royal visit (The Queen and Prince Phillip were showing young Prince Charles and Princess Anne around) at Western Springs Stadium, in March 1970. (The weather turned dreadful but 10,000 people attended and the show was live broadcast on TV.) Bunny earned a spot in the Superpop 70 line-up and Kevan Moore signed him up for his first appearance on new TV music show Happen Inn.

Just out of reach

His first performance in front of TV studio cameras was April 7, 1970 – the same week as his first single was released, a cover of Solomon Burke’s ‘Just Out Of Reach’ (written by Virgil “Pappy” Stewart and earlier recorded by Patsy Cline, among others) backed with a Ray Charles song, the Buck Owens-penned country classic, ‘Crying Time’.

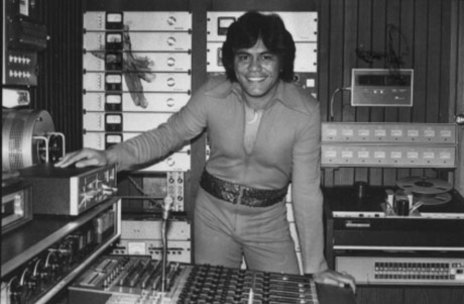

‘Just Out Of Reach’ was Bunny’s first studio experience. The songs were recorded in November 1969 at Stebbing Recording Studios in Herne Bay, Auckland. He was 16.

“That was at Stebbings, under the house. I even remember the name of the street, Saratoga Ave. Jimmie Sloggett did the arrangement, I think Benny and Russell Clark were the producers. I learnt it off an old Tom Jones album. There again you see, it was Tom Jones.”

“They brought the orchestra in there, everything was done in bits,” he told Unsung Heroes Of Māori Music. “It was very interesting for a Māori boy to go into a studio. I wish we could have done more takes – the producer said, ‘yeah that’s a take, that’s a wrap.’ I was thinking, ‘nah I can sing it better than that bro.’ I was just young, you know, sixteen.”

“And he’d fire; he just exploded every time he sang. I have never known Bunny to do a bad performance, ever.”

– Bernie Allen

“We started a new show, Happen Inn, it was a new series.” musical director Bernie Allen told Unsung Heroes, “Benny Levin arrived in with Bunny Walters and we put him on the show. We included him on more and more shows until at one stage, Bunny was in there darned near every week. He would come into the studio, he would perfectly know all his words. As soon as you put the track on Bunny’s face would light up. And he’d fire; he just exploded every time he sang. I have never known Bunny to do a bad performance, ever.”

Following ‘Just Out Of Reach’ were the singles ‘It’s Been Too Long’ and ‘Can't Keep You Out of My Heart’. They received airplay but failed to chart.

Bunny performed on other TV shows, including This Day and The Rock ‘n’ Roll Special, and in September 1970, he appeared on The Country Touch. He had just returned from performing at the Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan, where he sang daily at the New Zealand pavilion and made guest appearances with Inia Te Wiata and Kiri Te Kanawa. Japanese critics dubbed him the “Kiwi Dai-Kashu” or “New Zealand’s greatest pop singer”. The term was usually reserved for international stars like Elvis Presley and Tom Jones.

“I came back from there and turned professional. I gave up the day job and Benny [Levin] got me all these gigs.”

‘Just Out Of Reach’ received airplay in Japan and sold well. He was invited back – Levin and Clark were busy negotiating contracts for a return tour of Japan and Bunny also had a tour planned for the Philippines.

Japanese critics dubbed him the “Kiwi Dai-Kashu” or “New Zealand’s greatest pop singer.”

According to a clipping in West End News (27 January, 1971), over Christmas and New Year’s Eve in 1970, Bunny was playing at North Island beach resorts and by January he was straight back into the local hotel and club circuit. He’d been busy playing at teenage dances up and down the country as well. He had a tour of Australia planned.

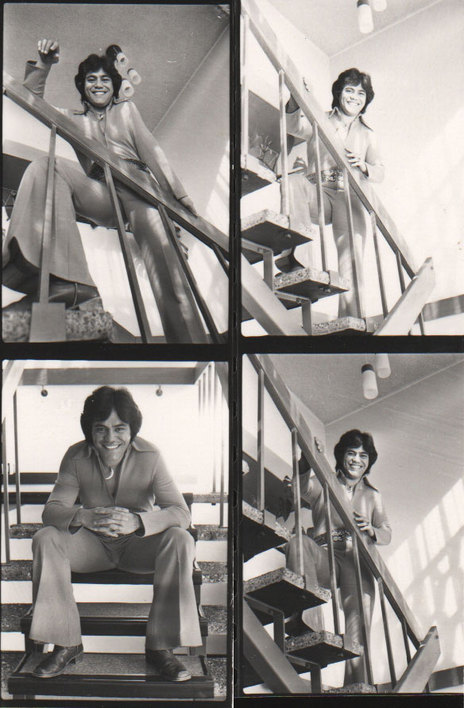

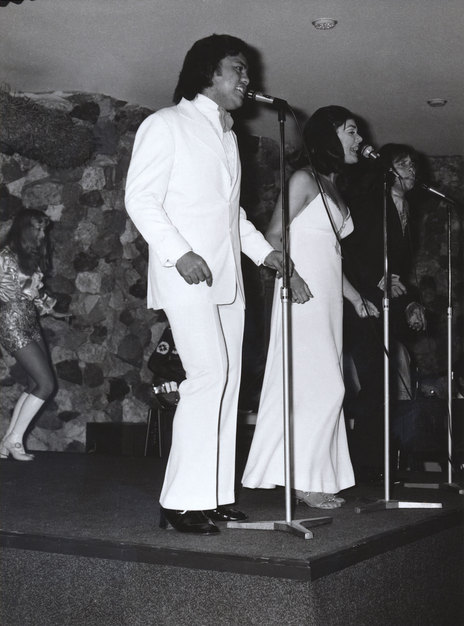

On September 11, 1971, Bunny Walters replaced Vaughan Davis as resident singer on Happen Inn, sharing resident vocal duties with Suzanne Donaldson. It was his biggest break so far, and he gave up a two-week engagement in Tahiti to secure the job. In just 18 months since his debut single was released, he had become one of the country’s leading entertainers.

The ‘Brandy’ myth

Bernie Allen worked on countless TV productions with Bunny, and together with established producer Peter Dawkins, he produced a number of Bunny’s recordings for Impact. Allen called on The Yandall Sisters to sing backing vocals for Bunny’s next single, ‘Brandy’, which was given the Midas touch by Dawkins.

Bunny’s version was a No.4 hit in NZ in April, 1972. It was released after the original version, by Scott English, who also co-wrote Jeff Beck’s ‘Hi Ho Silver Lining’ and The American Breed’s ‘Bend Me, Shape Me’. English’s original entered the British charts in October 1971 and reached No.12, entering the US charts in March 1972. As ‘Mandy’, the song became a No.1 hit in the USA and was internationally successful for Barry Manilow. The title was revised simply to avoid confusion with the 1972 US No.1 hit song, ‘Brandi You’re A Fine Girl’, by Looking Glass.

The local legend that Barry Manilow somehow knew of Bunny Walters’ version, that he was cashing in on Bunny’s success, is simply because Scott English’s original version is not very well known in NZ. Listening to the opening verse in Bunny’s version, you can hear a slight nasal twang, much like English’s vocal delivery. It quickly disappears as Bunny’s vocals open up, wide and strong. All together now: “You came and you gave without taking …” We all know which version is better.

Take the money and run

The singles kept coming, with ‘I Won’t Be Sorry To See Suzanne Again’, and the next hit; the Tony Christie-styled ‘Take The Money And Run’. Produced by Bernie Allen, it stayed in the Top 20 for 14 weeks, peaking at No.2 for three weeks in November, 1972. It was a finalist in the Loxene Golden Disc top 12.

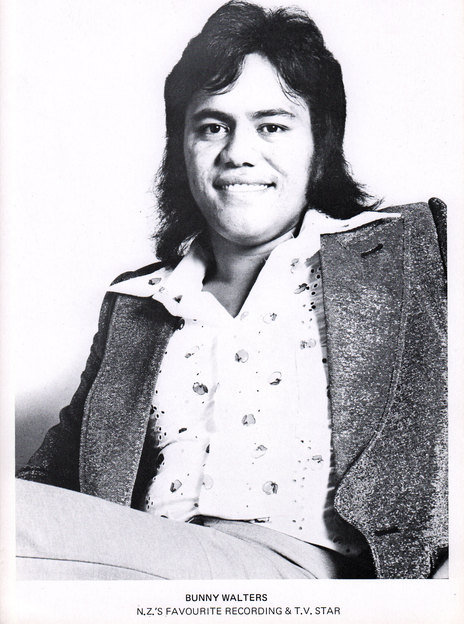

‘Brandy’ was so popular that Chappell Music published the sheet music with Bunny’s photo on the cover.

It was Bunny’s biggest hit, although ‘Brandy’ still takes the long-term popular vote. ‘Brandy’ was so popular that Chappell Music published the sheet music with Bunny’s photo on the cover, a rare acknowledgement of the selling power of a local performer.

The NZ Listener’s Sound-Round with Ray Columbus column of October 9, 1972, reported that Bunny had just finished a club season in Tahiti and represented NZ in Fiji with Happen Inn’s Kevan Moore, who was producing a trade show “Hello From New Zealand”. A couple of days later Bunny was one of three finalists (“last lap competitors” along with Yolande Gibson) for the Entertainer of the Year award, held at Trillo’s in Auckland. Bunny’s good friend and tour buddy Craig Scott won the award.

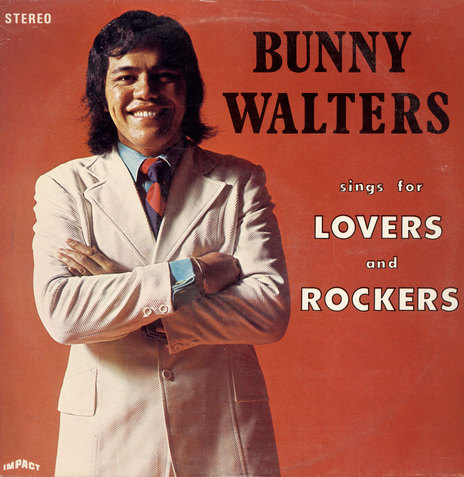

In 1972 Impact also released an LP, Bunny Walters Sings For Lovers And Rockers, with production credits split track by track between Peter Dawkins and Bernie Allen, who was the arranger for all tracks. The songs, all recorded at Stebbing/ Zodiac Recording Studio, include ‘Brandy’, ‘Take The Money And Run’, and ‘I Won’t Be Sorry To See Suzanne Again’, as well as popular standards of the day: Engelbert Humperdinck’s ‘Quando Quando Quando’, the Jimmy Webb-composed ‘Didn’t We’ (made famous by actor Richard Harris), Neil Diamond’s ‘Girl You’ll Be A Woman Soon’, the Neil Sedaka-penned Tony Christie hit ‘Show Me The Way To Amarillo’. Side two finishes with a nice surprise, a gutsy version of Otis Redding’s ‘I Can’t Turn You Loose’, where Bunny proves that in addition to being a deft cabaret and ballad performer, he’s every bit the soul man too.

The combination of regular TV performances, live shows and great singles on the airwaves made him a national star.

By now Bunny was huge. The combination of regular TV performances, live shows and great singles on the airwaves made him a national star. He would appear on TV around dinner time and hit the stage in a different city later the same night, playing to packed houses. He was treated like a star and lived the life of a star. He was being sent songs for consideration, including 10 from UK composer Les Reed, who co-wrote ‘There’s A Kind Of Hush’ and ‘Delilah’.

In February 1973 Bunny teamed up with the Symphonia of Auckland for two “rock symphonic” concerts. He sang standard pop and rock songs, including ‘Take The Money And Run’, with full orchestral backing.

His next singles were ‘Helena’, followed by ‘Home Isn’t Home Anymore’ released in February 1973, which only slightly troubled the chart at No.18. ‘The Nearest Thing To Heaven’, his final charting single, was produced by Alan Galbraith. It held a respectable No.10 chart placing in August 1974 and sold well in Melbourne and Sydney.

Bunny was again nominated for Entertainer of the Year in 1974, along with Ray Columbus and Steve Allen (it went to Columbus). He won two major RATA awards (Recording Arts Talent Awards – forerunner to the modern NZ Music Awards) in Christchurch that year, for Best Vocalist of the Year and Best Song of the Year for ‘The Nearest Thing To Heaven’.

Crying time

On October 20, 1974, Bunny, still very young at 21, was arrested for possessing cannabis and speeding. A city council traffic officer found a roach in his ashtray (“the remains of what appeared to be a cannabis cigarette”) and after more searching, turned up a "reefer” in a cigarette pack that was stashed under the dashboard. He appeared in the Auckland Magistrate’s Court on October 24, where his counsel said he was “not an addict or a peddler”. The judge convicted and fined him $100.

“I got busted … it was only a lousy little joint but it was enough to turn things around,” Bunny told Unsung Heroes in 2013. “The media got a hold of it; it was splashed across the papers. Today it’s not such a big deal, but back then it was and the media certainly had a field day. All the major papers jumped on it. I do regret it and it was a mistake, but another mistake of mine.

“I had just cut loose, I let it all go man. I was out there partying all the time, hanging out with the brothers that I shouldn’t have been. I started getting into drugs and booze and my first marriage dissolved. I just lost it and got carried away.

“I must fess up, I took it all for granted. I took my talent for granted. I got into a lot of trouble. All self inflicted, I got caught up in the party. I let the wrong people into my life. It’s all history now, it’s all gone. I look back now and I thank God I’m still here bro.”

Home isn’t home anymore

Work offers slowed for Bunny in the cabaret scene, although Benny Levin and Russell Clark hadn’t abandoned him. In mid-1975 they had him lined up for a TV show called Good Time; in August he toured with fellow Impact performer Erana Clark and emerging star Mark Williams; in March 1976 Impact released another single, ‘Never Too Young To Rock’. City News reviewer Julie Tiplady described it thus: “A really super party record and if you enjoy a good foot-tapping beat then you will really dig it.”

In April 1976 Bunny played shows at the South Sydney Junior Leagues Club (on a bill with singing, dancing variety act The Kessler Twins) where he was backed by a 15-piece band. He had trouble getting onstage as his union card wasn't processed in time. “Eventually they let me go on,” he says. He performed nightly to a crowd of 1400 in Newcastle and worked other clubs – North Sydney Leagues, Bondi Junction and Manly Warringha.

“You covered the whole range, you weren’t just a ballad singer. You had to do the whole enchilada.”

There was another Impact single, ‘Crazy’, in 1977, which he debuted on TV show Two On One on June 10, 1977, and he continued to perform through the 1980s.

Bunny had long been television’s go-to singer for cover versions of R&B songs like Billy Paul’s ‘Me and Mrs Jones’ or The Stylistics’ ‘You Make Me Feel Brand New’.

“Back when I cracked it and became known as this ballad singer, back then all the live gigs I did, you had to adapt,” he told AudioCulture. “You had to have all this variety in your repertoire. I’d sing the ballads, add a little bit of country, and finish with a rock and roll bracket. You covered the whole range, you weren’t just a ballad singer. You had to do the whole enchilada.”

By 1978 Bunny was helping out with a Labour Party political campaign song, ‘To Be Free’. A short-run pressing, it has a version of the song on the B-side called ‘To Be Free With Labour’.

Bunny’s career was on a slippery slope and Australia had proved a tough nut to crack. He had headed to Australia when life hit rock-bottom for him here, but the reality was that as an unknown, he found it hard to get by. He even worked as a brickie’s labourer.

“These hands weren’t made for lifting bricks. I didn’t last very long there,” he told the Ernie Leonard-produced documentary show Koha in 1986. “I came back from Oz and went through a bit of a spiritual awakening, I wanted to give it all away, be a family man again. But that was short-lived, I could never do it. The little performer inside was saying ‘carry on boy’.”

In the Koha interview with Bunny he is very humble, his public profile and live career are now quiet, although jingles were paying the bills. He was playing regularly at The Factory, a well-known centre for the South Auckland Black Power movement. “It’s a new thing for the gangs in New Zealand, he said. “Very relaxed atmosphere, good vibes, no violence. It’s a good buzz to be singing to these guys, their ladies, sometimes their kids. It’s a real good place to come and work.”

Bunny sang a whole lot of jingles throughout his career, working with writer-producers including Murray Grindlay, Bruce Lynch and Rob Winch. He told Koha, “I haven’t got a manager now, for the last two or three years I’ve being doing it myself. And it’s been going pretty well I must say. I haven’t made any drastic mistakes yet. I don’t think I will, I’m getting more positive every day.” The NZ Herald reported in August 1986 that together, Annie Crummer and Bunny Walters made up “80 per cent of all the male and female voices heard on advertising jingles.”

He may have been slogging it uphill, but as far as TV appearances went, he was still our Bunny and that big grin was still welcome. In 1985 he performed ‘Please Come Home For Christmas’ for a live TV audience, filmed at the Christchurch Town Hall. In 1986 there he was again, with All Of Us, an entertainment industry super group, taking part in the America’s Cup challenge promo single ‘Sailing Away’ along with Billy T James, Dave Dobbyn, Annie Crummer, Tim Finn and a whole bunch more. The single spent nine weeks at No.1 in 1986.

The same year he appeared on Dalvanius Prime’s Sweet Soul Music TV special, singing Rufus Thomas’s ‘Funky Chicken’ and Ray Charles’ ‘(Night Time Is) The Right Time’ with Mary Yandall, plus a Stax Records soul medley that included Arthur Conley’s ‘Sweet Soul Music’ and Wilson Pickett’s ‘Land of 1000 Dances’.

In 1991 Bunny, along with Annie Crummer, Dalvanius Prime and the Patea Māori Club, recorded a rousing version of ‘Pōkarekare Ana’, which was used as the TVNZ station ID and broadcast as broadcasting began each day. And In 1995 he took part in the Sir Howard Morrison special – Time Of My Life, singing Jackie Wilson’s ‘Reet Petite’.

Bunny continued to perform as much as possible. He collaborated with his old buddy Tom Sharplin and Ritchie Pickett: they called it Toru Tane Tour – three men on tour. He guested with cabaret revivalists The Hit List in 1996 at The Club in Queen Street along with Roy Phillips of The Peddlers. Somewhere along the way he also recorded a tribute, in te reo Māori, to Rangimarie Hetet, an expert Māori weaver.

As the sun goes down we’ll find a little town

In 1997 the headlines read, “70’s rocker turns his back on sex, drugs and rock'n roll lifestyle.”

Ultimately Bunny needed something stronger than showbiz to bring balance to his life. In 1997 the headlines read, “70’s rocker turns his back on sex, drugs and rock'n roll lifestyle.” In 1999, an Extreme Close Up documentary said, “Bunny Walters went from entertainment to alcoholism to drugs, only to be now teaching principles of reconciliation to maximum security inmates in a Canadian jail.”

So what happened to Bunny Walters? In Auckland, he joined a bible college and started singing songs of faith in church. “I finally realised that I was going nowhere fast,” he told AudioCulture. “I was just waking up and trying to find the next hit. Thinking, ‘let’s go to the pub and jump on the merry-go-round again.’ I just got sick of doing that. I made a decision to make a turn.”

Bunny bumped into Ruth, whom he had first met 25 years earlier, and fell in love. The pair married and shifted to Queensland, where they moved around before settling on Macleay Island, near Brisbane on the Queensland coast, where he got involved with the local church and community. Yes, he still performs, at various sports clubs in the area. And yes, as he sang in ‘Brandy’, happy people still pass his way.

--

Bunny Walters died 14 December 2016 at Waikato Hospital, aged 63. His wonderful singing voice and infectious smile will stay in our hearts.