Tom Sharplin

The band launched into a frenzied rock’n’roll number as a shadowy, leather-clad Tom Sharplin strutted through the crowd chewing gum and combing his greased-back pompadour. It was dark and he was wearing sunglasses. He hit the stage and snatched a microphone: “Well, it’s Saturday night and I just got paid…”

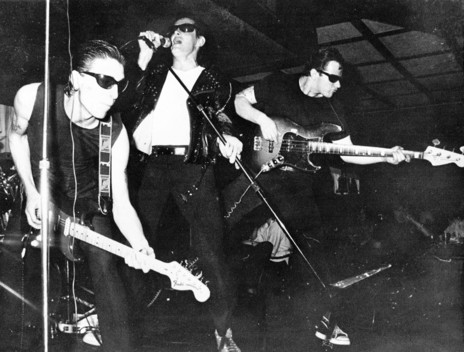

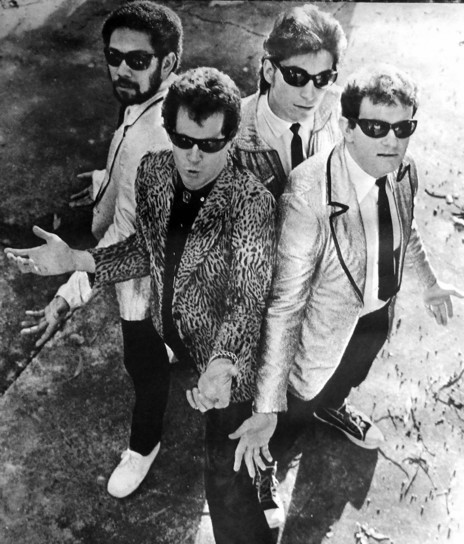

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs in the early 1980s. Left to right: Steve Edgar, Tom Sharplin, Al Dawson, Ray Eade.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin - Blue Moon (Mirage/ Music World, 1979)

A Variety Artists Club of New Zealand meet and greet in 2013. Left to right: Eddie Low, Suzanne Lynch, Tom Sharplin, Marian Burns.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

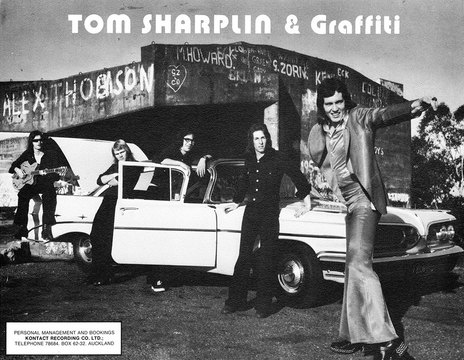

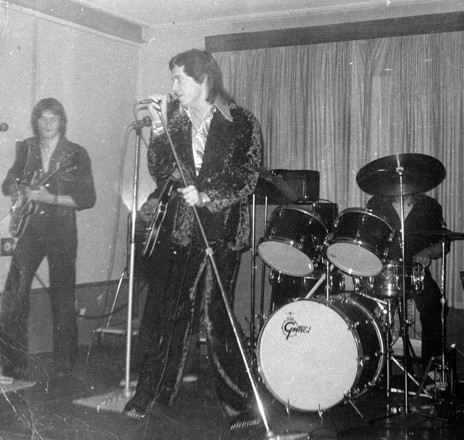

Tom Sharplin & Graffiti, mid-1970s. Left to right, Glenn White, Steve Osborne, Bill Wilson, Ritchie Pickett, Tom Sharplin.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Dennis Marsh with Tom Sharplin, 6 June 2014.

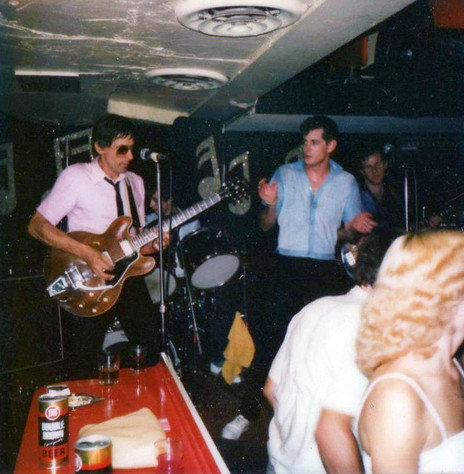

Tom Sharplin and the Rockets, Gluepot, May 1978

Photo credit:

Simon Lynch

Tom Sharplin - Love is a Beautiful Song (Pye, 1971)

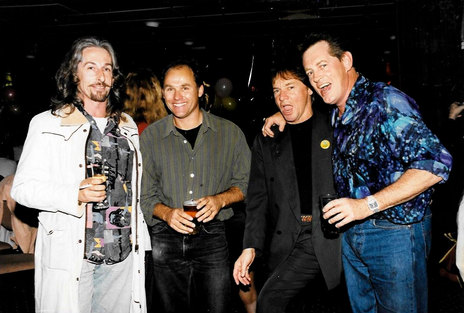

Ritchie Pickett, Rick Poole, Shane Hales and Tom Sharplin in the 1990s

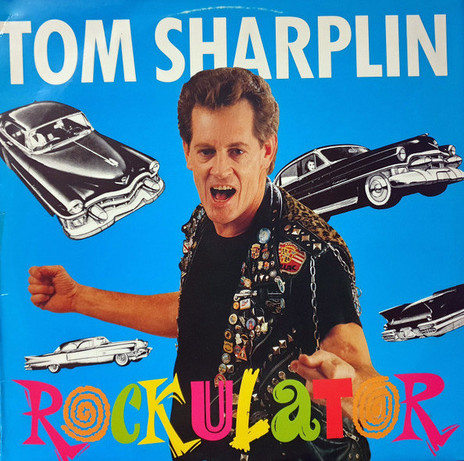

Tom Sharplin - Rockulator (RCA, 1989)

Tom Sharplin and The Rockets at the Awapuni Motor Hotel, Palmerston North, circa 1979. Left to right: Gary Havoc, Digby Day, Tom Sharplin, Ray Eade, unidentified.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

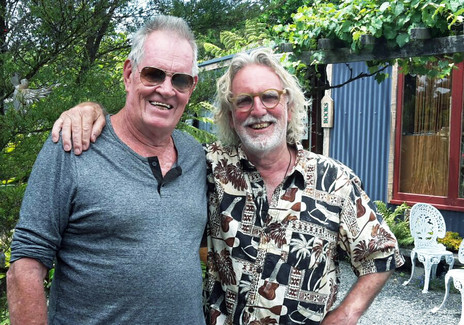

Tom Sharplin with Dick Frizzell, 2018.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Four Benny award winners and other friends celebrate Eddie Low's 70th birthday, Cambridge, 2015. From left: Gray Bartlett, Brendan Dugan, Dennis Marsh, Eddie Low, Kim Willoughby, and Tom Sharplin; at right are three of Rusty Greaves's 14 children: Michelle, Kevin and Lex.

Photo credit:

Gray Bartlett collection

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs in the early 1980s. Left to right: Ray Eade, Tom Sharplin, Rob Magnus, Dave Lovini.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Watch: Tom Sharplin rehearses and is interviewed for Joe Brown's Search for Stars in Rotorua (1970)

Tom Sharplin and The Rockets, late 1970s. Left to right: Malcolm Smith, Dave Lovini, Tom Sharplin, Glenn White, Jeff Clayton.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin - Heart Beat (Kontact, 1974)

Tom Sharplin and Graffiti at Te Rapa Tavern, Hamilton, circa 1974. Left to right: Glenn White, Tom Sharplin (in front of Bill Wilson), Steve Osborne.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Variety Artist Club stalwarts Tom Sharplin and David Hartnell present Gray Bartlett with his President's Award, 2017

Photo credit:

Gray Bartlett collection

On tour in the late 1980s. Left to right: Tom Sharplin, Bunny Walters, Māori Volcanics singer Robbie Ratana, Tania Rowles, Jan Cooper.

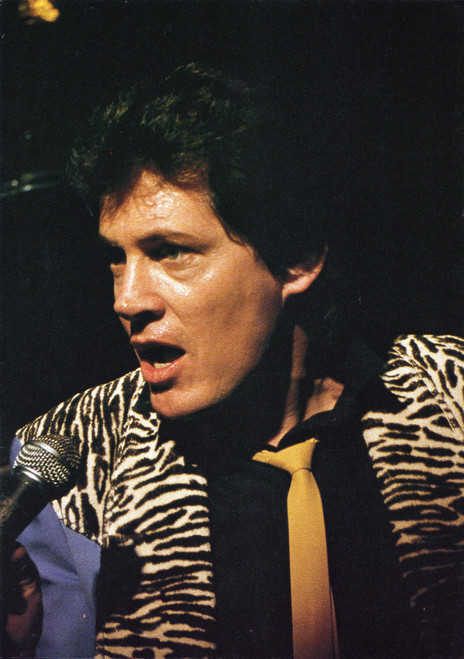

Tom Sharplin in the image used for the cover of the 1984 LP Nothing’s Better Than Rock’n’Roll.

Photo credit:

Roger Jarrett

Bunny Walters, Ritchie Pickett and Tom Sharplin

Tom Sharplin sings Rip It Up with Ray Columbus, Ray Woolf and others (1985)

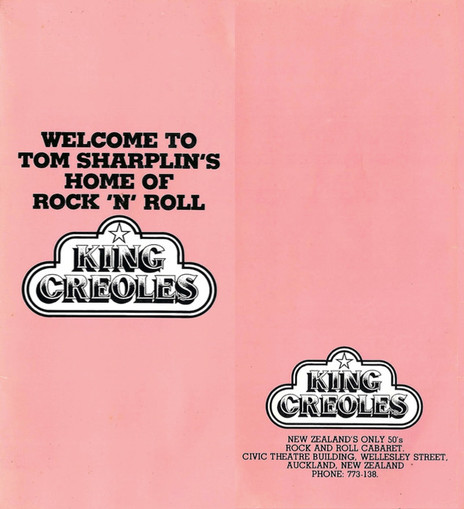

Cover of the wine and drinks list from King Creoles.

Photo credit:

Jane Jackson collection

Tom Sharplin sings Great Balls of Fire, Royal Variety Performance, Auckland's St James, 1981

Tom Sharplin and the Toner Sisters performing at the Hornby Club, Christchurch, 2017. Left to right: Lynne Toner, Celine Toner, Tom Sharplin, Adrienne Toner.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin and Graffiti at Te Rapa Tavern, Hamilton, circa 1974. Left to right: Tom Sharplin, Glenn White, Bill Wilson, Steve Osborne.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs on the set of Bless My Soul It's Rock and Roll, 1985. Left to right: Ray Eade, Tom Sharplin, Brian Lorimer, Al Dawson.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

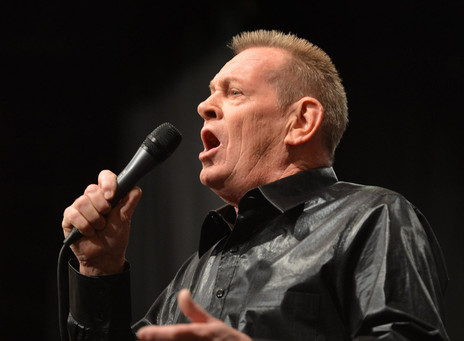

Tom Sharplin in the 2010s.

Sessions for the 1989 Rockulator album, produced by Billy Kristian at Mandrill Studios. Left to right: drummer Dave O’Connor, ‘You’re The Voice’ songwriter Chris Thompson, Ray Eade, Tom Sharplin.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

On stage for a TVNZ production in 1985. Left to right, Pat Kearns, Midge Marsden, Tom Sharplin, Maree Humphries, Ritchie Pickett.

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs at King Creoles, circa 1983. Left to right: Al Dawson, Steve Edgar (drums), Tom Sharplin, Ray Eade.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs at Oscar’s nightclub, circa 1982. Left to right: Rob Magnus, Tom Sharplin, Ray Eade.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin and Suzanne Lynch in 2015.

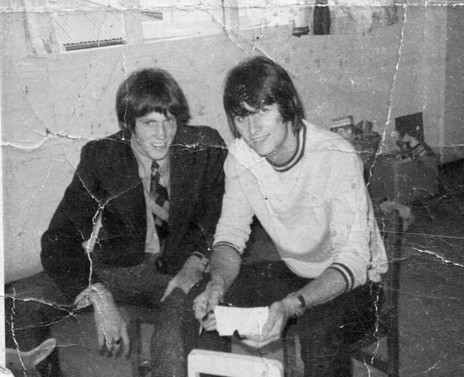

Tom Sharplin (left) and Mr Lee Grant at rehearsals for a short Bay of Plenty tour, 1967.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

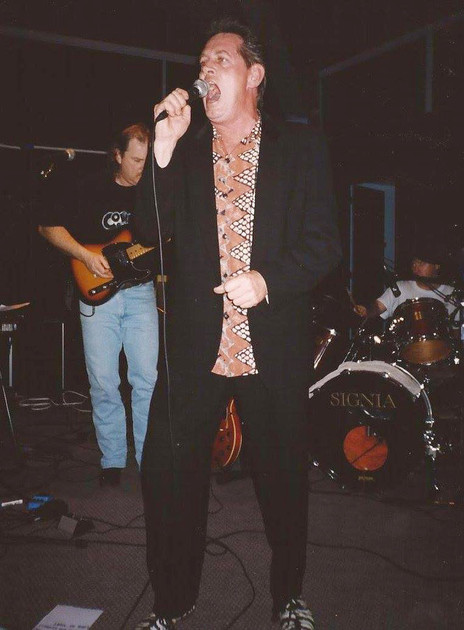

Tom Sharplin performing in Tauranga in the 1990s with Chris Gunn on guitar and Paul Higgins on drums.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs, 1980. From left: Dave Lovini, Tom Sharplin, Rob Magnus, Ray Eade.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Rock Around the Clock (1981)

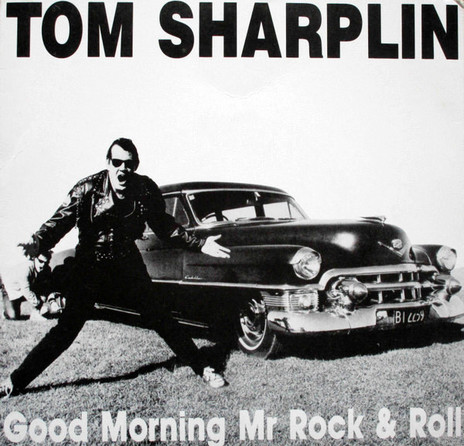

Tom Sharplin - Good Morning Mr Rock & Roll (RCA, 1990)

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs, circa 2017. Left to right: Bruce French, Gordon Joll, Tom Sharplin, Ray Eade, Steve Hubbard.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

The Go New Zealand Tour, March 1985. Left to right: Bob Paris, Adele Yandall, Bruce Morley, Tom Sharplin, Midge Marsden, Suzanne Prentice, Ritchie Pickett, Michael-Roy Croft.

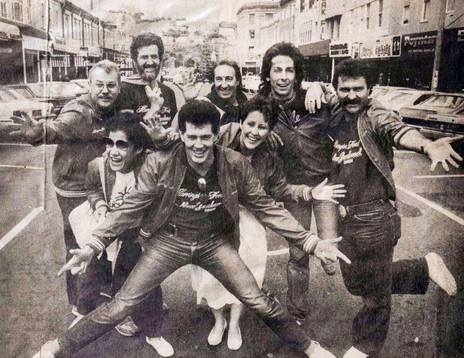

The Harrington Ford And Associates Go New Zealand Tour in full swing, early 1985. Back, left to right, Andrew Kimber, Kevin Coleman, Bruce Morley, Sid Limbert, Paddy Long, Bob Paris. Front, left to right, Midge Marsden, Suzanne Prentice, Ritchie Pickett (at piano), Tom Sharplin, Michael Roycroft, The Yandall Sisters – Mary, Adele, Pauline.

Photo credit:

Michael Roycroft collection

Tom Sharplin (left), Bunny Walters (centre) and Ritchie Pickett at Burkes Pass in the South Island.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Dave Maybee (left) backing Tom Sharplin at Hamilton Lake with Paul Kunac on drums and Mike Parker on bass.

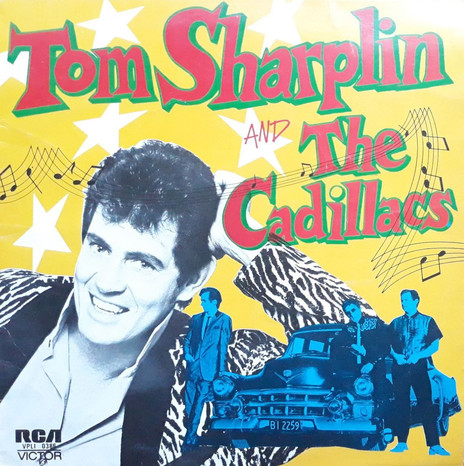

Tom Sharplin and the Cadillacs (1982)

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs at King Creoles in the early 1980s. Left to right: Graham Silcock, Tom Sharplin, Ray Eade.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin and The Cadillacs at the Mandalay in Newmarket, Auckland, in the 1980s. Neville Hall on saxophone and (from the top) Keith Clarke, Ray Eade, Tom Sharplin, Dave O'Connor and Brian Hatcher.

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

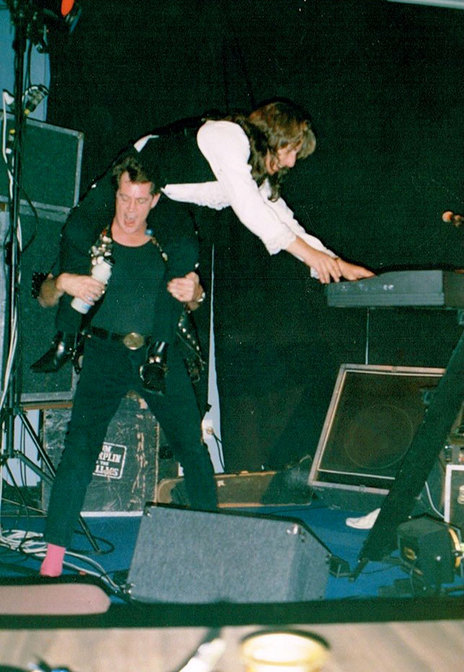

Ritchie Pickett on the shoulders of Tom Sharplin, early 1990s

Photo credit:

Tom Sharplin collection

Tom Sharplin out front with The Rockets at the Gluepot, Auckland, 1978.

Photo credit:

Simon Lynch

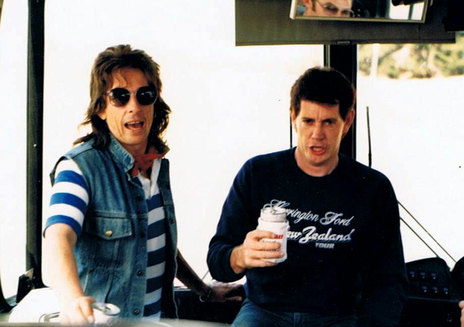

Ritchie Pickett (left) and Tom Sharplin on the Go New Zealand Tour bus, 1985

Photo credit:

Paddy Long collection

Five Benny Award recepients gathered in Orewa on 16 February 2025 to celebrate the induction of Suzanne Prentice and Carl Doy into the New Zealand Walk of Fame. From left: Tom Sharplin, Brendan Dugan, Suzanne Prentice, Gray Bartlett, and Carl Doy.

Photo credit:

Charles West

Discography