AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

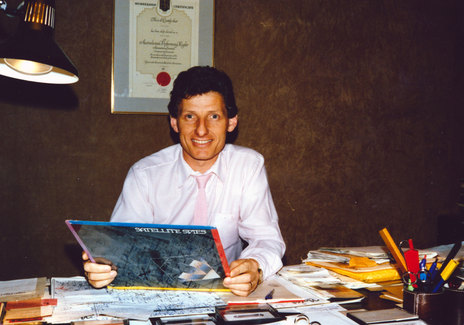

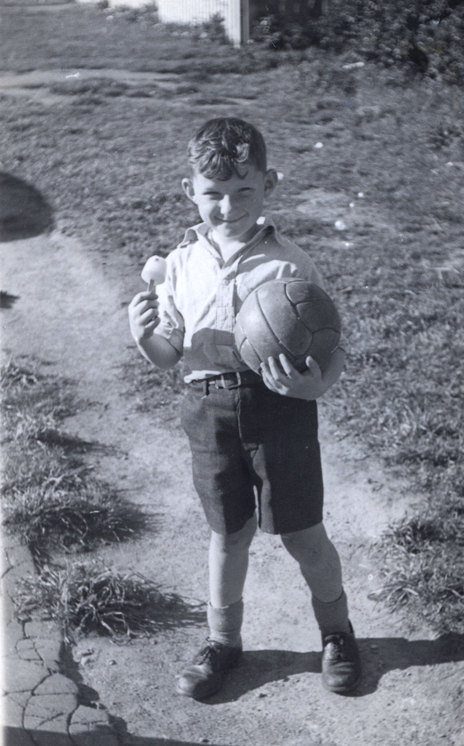

Glyn Tucker

aka Glyn Tucker Jnr, Glyn Conway

In the 1980s, the studio recorded the big-selling debut albums by The Dance Exponents and The Mockers and the milestone album Dave Dobbyn’s Loyal. Tucker had success with his record labels Mandrill and Reaction and is well qualified to look back at the fizz and the pop and the art and the commerce of the hit single.

Early years

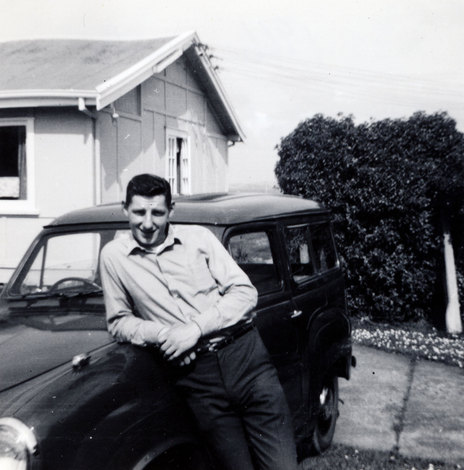

Glyn Tucker Jnr grew up in Miramar until he moved to Upper Hutt in 1954 at the age of 11 years old. Tucker has used “Jnr” to avoid confusion with his late uncle, the well-known radio and TV sports broadcaster who received an MBE for his services to the horse racing industry. As a child Tucker Jnr played piano, violin and chromatic harmonica, the latter under the influence of The Goon Show.

Tucker first heard rock and roll on local radio in 1956. The songs that got his attention included ‘That’ll Be The Day’ by Buddy Holly, ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ by Elvis Presley, ‘Shake Rattle And Roll’ by Bill Haley and ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’ and ‘Tutti Fruitti’ by Little Richard.

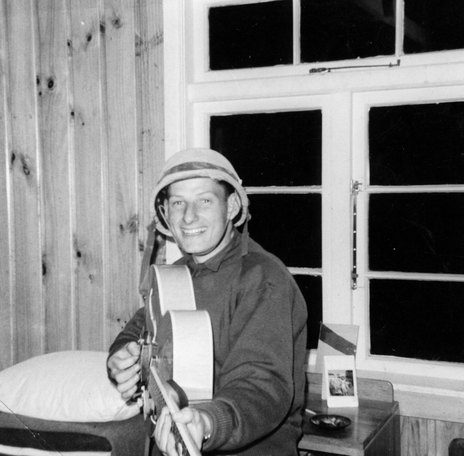

“I got into those,” recalled Tucker in 2015, “and I wanted to play guitar. With no television the only way of seeing these artists was the occasional movie. A huge influence on me wanting to get a guitar and learn to play it was the movie The Tommy Steele Story (1957) – the story of his rise to fame.” Teenage Tucker didn’t see live bands in Upper Hutt: “at the Bible class dance, we just played records.”

I had heard the term ‘electric guitar’ but I did not know what it was. There was no one to teach us how to play electric guitar.”

– Glyn Tucker

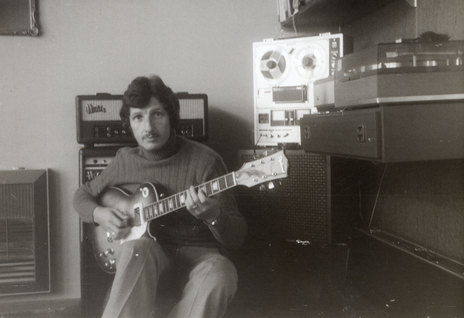

When Tucker first saw Buddy Holly holding an electric guitar, it may as well as have been a flying saucer, it didn’t look like his £5 acoustic guitar – a UK brand Antoria “f” hole. “I had no idea how to make my guitar sound like Buddy Holly. I had heard the term ‘electric guitar’ but I did not know what it was. There was no one to teach us how to play electric guitar.”

“I learnt you could add a pickup,” said Tucker, “but it still sounded the same. Then I realised you had to have amplification.” Tucker went electric after a family friend transformed a valve radio into a homemade amplifier.

At 14, the Tucker family moved to Auckland: “I thought, that’ll be cool – Johnny Devlin had his first couple of records out – I thought we might see him at the Jive Centre, but he had moved on.”

“The family settled in Howick where I hooked up with Paddy McAneney (guitar) and Roger Wiles (drums) and we did crude covers of the hits of the day. We played the odd bible class dance or functions where there was no budget for a real band.”

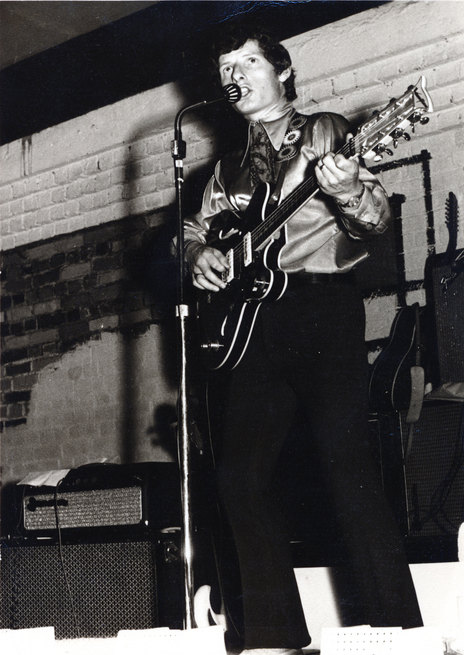

Wiles and McAneney would be the core of The Gremlins a few years later but Tucker wanted to gain some experience playing with other musicians. Christmas 1959 is memorable for Tucker as he he met his wife Carole and he auditioned for his first professional gig. The 17 year old Tucker joined Ian Lowe And His Stereotones to play a Prestige Promotions summer dance season (Boxing Day to New Year’s Eve) at the Ruakaka Town Hall – just south of Whangarei – backing the headliners Vince Callaher and Kahu Pineaha.

“A mate of mine – Mike Dolan from Bucklands Beach – and I got paid £1 each per night as vocalists for The Stereotones,” said Tucker. “My first pro-gig ever. Ian Lowe was a lot older than us. He was about 35 years old, a rhythm guitar player. He seemed quite keen to get some younger musicians around him, so he could boss them around and show them the ropes.”

Lowe chose some great players, including 18 year old Gray Bartlett on guitar, Bruce King on drums and standup bass player Rick Laird who went on to play jazz in New York. In the pre-Beatles era there weren’t many singers that also played instruments. Tucker was sometimes billed as Glyn Conway – “a bit of a joke at the time,” said Tucker. “When we came back to Auckland we were introduced to Phil Warren and we trawled through a whole lot of unreleased 45s. I selected Chuck Berry’s ‘Carol’. I was not thinking of my girlfriend at the time, I was thinking of the music.”

‘Carol’ was selected to record at Eldred Stebbing’s Saratoga Street garage and Tucker wanted his friend, guitarist Paddy McAneney to play, so there were twin lead guitars – with Errol Timbers also playing. “I had sung it 100 times before we got it right, so my voice was stuffed,” recalled Tucker. Two thirds of the evening had been spent on the A-side. He is dismissive of the B-side, “I’m embarassed by ‘I’m In Love’ – it filled up the B-side – I think it’s crap. I always wanted to be a songwriter. I wasn’t one yet.”

The 1960 release billed as Glyn Tucker With Ian Lowe & The Tornadoes, on the Zodiac label, did not get played on radio as the NZBC did not buy it. 'Carol' got played on the Howick milkbar jukebox as Tucker gave them the 45 – Tucker still remembers how amazing it was to "have your own 45."

Tucker’s B-side composition ‘I’m In Love’ featured on John Baker’s 2004 compilation: Get A Haircut - 31 Of The Best New Zealand Rock'n'Rollers Ever!

In 1960 Tucker successfully auditoned for teen idol Ronnie Sundin’s band. After working with Sundin, the band continued on as The Embers and were the first resident band at the teenage dance club, the Shiralee, Customs Street West, that later became Galaxie. In the Embers were Gary Daverne (piano, saxophone) formerly of Red Hewitt and The Buccaneers and bass player Keith Graham from Johnny Devlin’s Devils.

“Later in 1960, I quit the residency with The Embers to take up an offer of compering and singing at the Saturday night Papatoetoe dance,” said Tucker. “It was cool being in the city but I made as much on one night, as I had at the Shiralee.”

“The early 60s era – just prior to the Beatles – was no man’s land musically. I was even singing Sinatra songs. The band I worked with was The Saints from St. Heliers. I did that gig for about four years and it was easy and enjoyable. They had the supper waltz and served a cuppa tea and biscuits,” Tucker laughs.

Their band was then known as The Adventurers, but they changed their name to The Gremlins and played the Papakura dance until August 1965.

Tucker’s staples included Bobby Darin rock and roll from ‘Dream Lover’ to ‘Multiplication’ and Darin’s jazzy ‘Mack The Knife’ plus Frank Sinatra’s ‘Tangerine’ and ‘You Must Have Been A Beautiful Baby’.

The Saints quit the gig near the end of 1964 and Tucker asked his old mates from Howick to join him – Paddy McAneney and Roger Wiles. Their band was then known as The Adventurers, but they changed their name to The Gremlins and played the Papakura dance until August 1965.

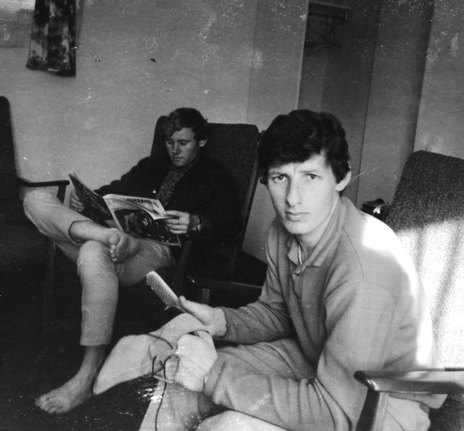

The Gremlins

In 1965 The Gremlins recorded their debut single ‘But She’s Gone’ b/w ‘Don’t Ya’, two Glyn Tucker originals, for the Allied International label, but that year the Army came knocking and The Gremlins disbanded.

“I got drafted to do three months in the army. We had just auditioned an organ player – it was Bruce Howard who ended up in The La De Da’s. In the three-month period we were defunct he hooked up with The La De Da’s and played on ‘On Top Of The World’. I came out of the Army really keen.”

“In 1966 ‘The Coming Generation’ was a No.2 hit only held off the No.1 spot by The Beatles’ ‘Yellow Submarine’,” recalled Tucker. “The Beatles were No.3 with ‘Eleanor Rigby’. We were in the Gold Disc Finals 1966 and 1967. We did the Gold Disc tour with Larry’s Rebels and The Avengers in 1967.”

One of the writers of ‘The Coming Generation’ is credited as “Tucker” but the writer is in fact Annette Tucker, who along with Nancy Mantz also wrote ‘I Had Too Much To Dream Last Night’ for The Electric Prunes.

‘The Coming Generation’ was on friend – from The Embers – Gary Daverne’s Viscount label, but their next release was on the Zodiac label.

“Not long after ‘The Coming Generation’ was released Gary took off to England to work as a school teacher. He was always full time teacher and part time musician. He had a deal with Eldred Stebbing. In those days to make a record was fantastic. If you made a record that got played on the radio you felt like you were God. We didn’t even realise until the records were pressed that it was on a different label.”

When asked about the sound achieved in Eldred’s Saratoga Street basement, Tucker had one gripe: “The only thing I didn’t like was that the amount of distortion on the final 45s was gross, compared to the master tapes. They’d over modulate. The whole idea was they wanted to make 45s sound loud.”

“In a three hour session we’d cut a single and do the flipside. Sometimes it took as long as four hours and we thought, ‘Shit, we’re so bad, it takes all this time to get this damn thing right.’ ”

“In today’s era you can get everything perfect, back then you went with more of the overall vibe. Because everyone was playing together there could be little things that you did not pick up on. Back then you would go into the studio and at the end of three hours you had a hit or had shit. Now you can go into a studio and work on something for a week, then you do the final mix and realise, ‘God you only had shit’. What a shame, it took a week to find out.”

When asked whether the 60s was a golden age for music, Tucker said, “Yes I do. There were a lot of places to play. Teenagers went to school, church or town hall dances. When we did that Gold Disc tour it was riotous. Screaming fans wouldn’t let us on the bus.”

“The Gremlins were very much pop as opposed to the R&B bands that were popular in the 60s. I relate us more to The Kinks and Lovin’ Spoonful. From day one I wanted to do original songs. We recorded mostly original songs. None of The La De Da’s, Larry’s Rebels or The Underdogs hits were originals. But the biggest hit we ever had – ‘The Coming Generation’ – I didn’t write.”

The Gremlins have not been reissued as often as The La De Da’s and Ray Columbus and The Invaders and have a lower profile with local vinyl aficionados. But the group had an extensive feature in John Baker’s Social End Product magazine (1995) and a 22 track collection by The Gremlins – Blast Off 1965-1968 was released by EMI in New Zealand in 2004 and on the Rev-Ola label in the UK in the same year as The Coming Generation: the Complete Recordings 1965-1968.

In the 1960s the group also had a lower profile in Auckland’s inner city unlicensed teen dance venues. “We did the Shiralee, the Top 20 and the Monaco two or three times,” said Tucker. “The resident bands were getting paid peanuts. We were making a lot more money by playing out of town, making day trips to Whangarei or Hamilton.”

The scene was competitive: “Larry’s Rebels had just came back from Aussie and their big coup was they’d added a strobe light. We picked up on that and we added psychedelic lighting to what were doing.”

“With my songwriting we went through a psychedelic period but we weren’t quite as square as Scott McKenzie ‘San Francisco, wear a flower in your hair’, but we weren’t as far out as Moby Grape and Jefferson Airplane. But all those influences were definitely there. A song I wrote ‘Blast Off 1970’ in 1967 had the same theme as David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’, he wrote years later, but he wrote a better song than I did.”

Tucker does not consider it to be the best track he wrote: “It was probably the most honest as it was a genuinely original song, whereas I did a song that was a straight rip-off of the Troggs called ‘You Gotta Believe It’. For a straight pop sound, that’s the best song but as an experiment ‘Blast Off 1970’ was a bit more adventurous.”

Keith Richards' amp

Tucker saw both The Beatles and The Who but it was the latter who impressed, “by far.” He missed the Stones shows but got the coolest souvenir.

He missed the Stones shows but got the coolest souvenir.

“I did buy Keith Richards’ amplifier,” said Tucker. “We couldn’t buy Fender and Gibson guitars or Fender amplifiers because of import restrictions protecting local manufacturers. So when promoters brought the acts out they’d do a deal where the acts would bring their equipment and leave it here.”

“It was a great amp, I was really sorry I had to sell it to buy a house. It was quite small, a Fender Concert. It was a 50-watt valve amp but it was unique in that it had four 10-inch speakers. Four 10-inch speakers really kicked arse. I only played rhythm guitar, so it was a bit of a waste. It still had a little bit of egg on the grill where eggs had been thrown at the band in the South Island.”

Married with two children, Tucker quit The Gremlins in 1968 and worked by day selling musical instruments for Hawke’s Bay Agencies and by night playing resident gigs. “I guess after 1968 I decided, ‘no we weren’t going to be stars’ – not international stars anyway. What I wanted to do was pursue my songwriting.

Mandrill

As a songwriter, Tucker saw the need for an inexpensive demo studio, so songwriters did not have hire a fully professional studio. In the previous two years Tucker had five of his songs performed on the high viewership TVNZ talent show Studio One, including ‘Highway Driver’ by Link and ‘You Can’t Pick Horses’ by Bunny Walters.

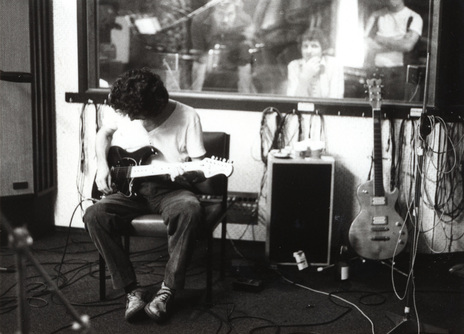

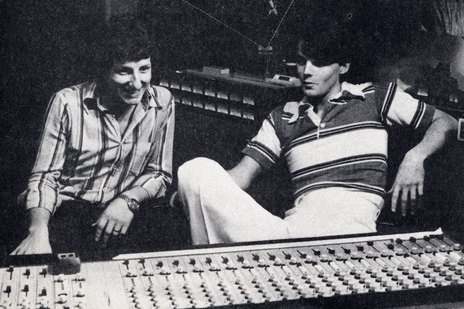

The first Mandrill Studio did their first recordings in early November 1974 at Rexall House, 41 Customs Street West. The advert in Hot Licks (March 1975) read “Full 4-Track Recording Facilities – Specialists in Demos for Songwriters or Groups – Rates $15 per hour.” Tucker and Dave Hurley pooled their resources to build this small basement studio. “I had a 4-track Teac tape recorder,” recalled Tucker. First band to record were Cherry Pie and they “put in quite a lot of time in construction.”

Back in the day, this writer photographed Cherry Pie at the new studio and I have never seen so many egg cartons in my life. Dave Hurley was also formerly a professional musician (The Breakaways) and as he and Glyn had both planning on starting a studio, they decided to work together. In the words of Hot Licks “the only ‘ogre’ in the scheme – LACK OF BREAD! Still, by pooling equipment and funds, they were able to budget for a low-cost studio.”

The funds went into the best sound gear they could afford – “mixers, tape-recorders, mics, reverberation plate, tape-echo, compressors, piano.” With little budget for décor, they concentrated on the acoustics of the space – “combinations of egg-carton fillers, acoustic tiles, peg board and Pinex were used for the acoustic treatment.”

Henry Jackson’s group Cherry Pie did the studio’s sound-testing trial runs and then recorded a 12-song demo tape. In their first four months musicians to use the Customs Street studio included the early Split Ends, Tole Puddle, Paul Bennet and Murray Grindlay.

Tucker was also moonlighting as bass player with the group Copperfield at The Masonic Tavern, Devonport. He would use that band if he needed to record an advertising jingle.

It was not until March 1975 that they declared the first Mandrill studio “officially” open for business.

It was not until March 1975 that they declared the first Mandrill studio “officially” open for business in Hot Licks magazine, but due to redevelopment of the downtown area, they immediately had to find new premises. They moved to 60 Parnell Road (corner of Earle Street) in May 1975 and started operating in June.

The first single recorded at the Parnell studio was the ‘Tropical Paradise’ by Human Instinct that was released in October 1975 on Pye’s Family label. They also recorded a single for Larry Morris and demos by John Hanlon, Think and Layton and Trent from TVNZ’s Opportunity Knocks.

In Hot Licks April 1976, Jeremy Templer wrote, “They’re still using a four track system. ‘While it’s much harder,’ Glyn Tucker claims ‘they can get virtually the same results as with a 16-track mixer.’ At a cost of $40,000 a 16-track system isn’t cheap but Glyn and Dave have 16-track equipment on order. Glyn is confident they will be able to offer full 16-track facilities in about six months.”

The Mandrill label

In 1977 Mandrill upgraded to a 16-track Ampex two-inch tape recorder. “The first two albums we did were an album by Waves [Misfit, released on Record Store Day 2013] which was fantastic, and Rick Steele’s album. I loved the Waves album,” recalled Glyn. “We were recording that for WEA as high quality demos on 16-track. They were quickly followed by Alastair Riddell and Citizen Band albums on the Mandrill record label.”

“I always wanted to run a label but I didn’t realise until many years later how difficult it was to run a studio and a label. You can’t be in two places at the one time. I was more interested in the music and the artist than label building. I didn’t envisage a label empire, it was just a means of making music and getting it out there.”

Choosing Parnell for their studio – the location of choice for many advertising agencies in the 1980s – was not intentional. “It was accidental, a stroke of good luck,” said Tucker. “We soon realised we were in a good place and we were in the basement of the building that housed Ogilvy And Mather!”

American record producers

Tucker’s Parnell studio was enlivened in January 1979 when eccentric six foot five inches tall, Californian record producer Kim Fowley (Runaways, Helen Reddy etc.) landed on his doorstep looking for the “new Beatles”.

“I played him all the stuff I’d done and he hated it all,” said Tucker. “Then I started playing him other local music including Street Talk’s first single. Kim really liked Hammond’s voice.”

That night Street Talk were playing the Windsor Castle in Parnell Rd so Tucker introduced Kim to the band and they went back to the studio and by 8.30am the following morning they had selected the songs for an album and co-written the single ‘Street Music’. Seven days later the album was mixed and three weeks later it was on the street via WEA.

Tucker later worked with another US producer in June 1979 when Jay Lewis produced the Citizen Band album in Mandrill Studios. “Jay Lewis was a different kind of producer, he was much more technical and focused on how to mic things up etc.

“One thing I learned from Kim was when I played him a new song – if he hadn’t got it in the first sixteen bars or even eight bars – he didn’t want to know,” said Tucker.

“Songwriting – I learnt that once you’ve done verse, chorus, verse chorus – you had better do something else – a solo or a bridge, but a solo is a cop out. I applied that to The Mockers’ ‘Forever Tuesday’. Andrew didn’t have a bridge. I had him go away and write a bridge. Andrew Fagan and Tim Wedde (keyboards) came back with a most amazing bridge that made the song.”

When asked how Fowley’s Street Talk album rates alongside other recordings made by the studio, Tucker replied, “I don’t think it’s Mandrill at its finest, we had limitations in our old studio. We did better albums in the new studio, for example the Bruce Lynch produced second Street Talk album or Dave Dobbyn’s Loyal produced by Mark Moffatt. All the bands that did work with Kim did learn from him.”

Fowley liked the songwriting of the Wellington group Spats which lead to a name change and Tucker recording the debut Crocodiles album featuring new singer Jenny Morris. The single ‘Tears’ was the pure pop that Tucker loved but, “I shopped it around the labels and only RCA were interested. I was shocked. I thought it was great but at first, nobody wanted to know.”

Tucker’s friend, Gary Daverne – from The Embers and the Viscount label – was an investor in the studio in 1977 when Mandrill updated to 16-track. Tucker and Daverne produced several projects together at the studio including albums by Billy T. James and the Maori Hi-Marks. The first Hi-Marks album Showtime Spectacular With The Hi-Marks was recorded in 1979 and sold platinum when first released by K-Tel. In 2013 Universal issued The Best of The Maori Hi-Marks on CD and it sold over 4,000 copies.

Toy Love

One of the last music projects at Mandrill on Parnell Road was the recording of the recording of Toy Love’s first two singles. ‘Rebel’ b/w ‘Squeeze’ were recorded in July 1979 and ‘Don’t Ask Me’ b/w ‘Sheep’ were recorded in January 1980.

When asked whether it was a fun session, Tucker replied: “No, it was relatively hard work because their equipment was shit. Their drum-kit rattled and it had a rotten sound and the guitar amp rattled, buzzed and squawked. We had a few hassles getting a reasonable sound but I was really impressed with Chris Knox’s vocals.”

“That was a genuine producer’s job because I went out to their rehearsal and had a listen to the songs. I don’t think I made any changes and I think if you listen to them now, the structures were already correct. I thought we got a good end result. At the end of the day I thought we both had a mutual respect.”

Mandrill in York Street

In 1980 Tucker brought in a new partner, Bruce Lynch, and built a bigger studio in York St. “Bruce Lynch came back from London where he worked with Cat Stevens and brought in some extra equipment including a 24-track tape machine that featured in the video for ‘Back in the Old School Yard’.”

Mandrill did not only record rock music. Tucker recalled: “We did a lot of jazz and Polynesian music for Ode. The first time Terence O’Neill-Joyce (Ode) rang to book a session, he booked two hours. I rang him back so I could get organised and Terence said, ‘It’s just a group, an Island group.’ I thought we were doing a single because there was only two hours. It turned out we were doing two albums.”

The head Mandrill engineer in the 1980s was Graeme Myhre. “Bruce Lynch suggested we should entice him to come back from England,” said Tucker, “as he had done a lot of sessions with Bruce and with producer Tony Visconti (David Bowie, Thin Lizzy etc).

1981

The April 1981 RipItUp had a feature on New Zealand’s 24 track studios – Harlequin, Mandrill, Marmalade and Stebbing – with Tucker confidently saying: “I’m supremely optimistic about the state of the industry at the moment. Radio airtime and charts are far healthier with local music than they have been in a long time. We are fast getting into a situation where the next Split Enz will do it direct from New Zealand.”

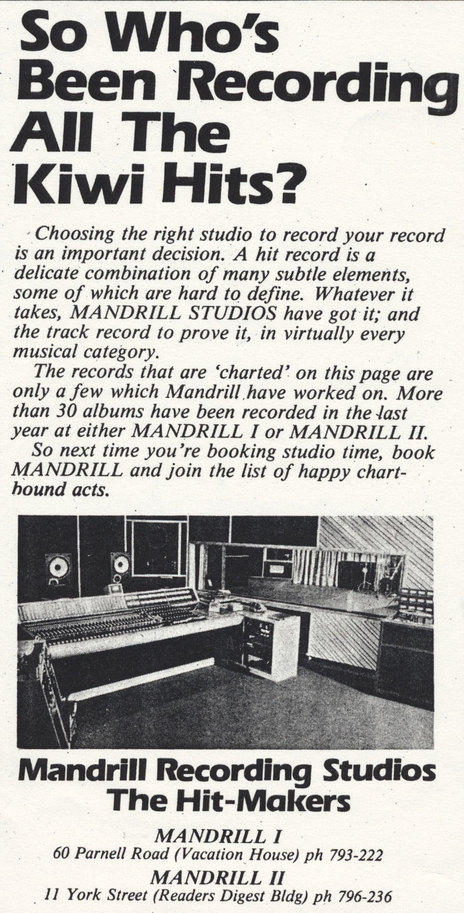

As an advert in the same issue Mandrill was able to print the NZ Sales Charts for March 29, 1981 with five singles recorded at Mandrill and four albums highlighted. The singles were by Deane Waretini, Coup D’Etat, Pop Mechanix, Dave McArtney and The Knobz while the albums were by Dave McArtney, Coup D’Etat, Billy T. James and The Hammond Gamble Band.

At that stage the second 16-track Mandrill Studio (60 Parnell Road) was known as Mandrill I and the 24-track studio at 11 York Street was known as Mandrill II. This twin location did not work well. Tucker found that if you wanted a piece of gear, it was invariably at the “other” studio.

1983

In a recording studio feature in RipItUp August 1983, Mandrill boasted of having recorded 83 albums and over 88 singles and EPs since 1977. Tucker includes as one of the three aims for the studio: “To record and promote New Zealand music and take it to the world.”

Tucker became a regular participant in the New Zealand trade contingent that took local music to the annual music industry trade show Midem in Cannes, France. In 1987 Tucker had a different album to sell, it was Lovin Feelings recorded by pre-Baywatch David Hasselhoff. “He came to Midem and we never had to queue for restaurants or anything, which was a real buzz, even in France they knew ‘Michael Knight’ and Knight Rider.” The album sold best in Germany and a few years later a German company recorded a No.1 disco hit with Hasselhoff.”

A film company had brought the project to Tucker and the album was recorded for marketing on American television. The original concept fell on its face when it failed at test marketing in the United States. European sales became crucial and Midem was the doorway to Europe.

Their 1983 advert also featured their “new USA state-of-the-art Trident TSM mixing console with capacity to mix up to 56 tracks of music and effects.” This gear was engineer Graeme Myhre’s choice and was similar to gear he had used working for Toni Visconti on albums like David Bowie’s Stage.

Reaction label

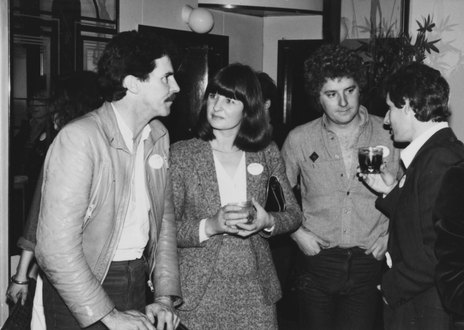

A second, hipper, record label called Reaction brought Trevor Reekie on board in 1981 with a diverse roster including Danse Macabre, Marginal Era, Penknife Glides, The Mockers, Satellite Spies, National Anthem and Everything That Flies. After Reaction, Reekie started the Pagan label in 1985.

1984 was the year the Reaction label had its biggest success with the double-platinum Mockers debut Swear It’s True.

“Trevor was more in touch with street level. During our association he was able to learn about production in the studio,” Tucker said. “We co-produced a lot of recordings.”

1984 was the year the Reaction label had its biggest success with the double-platinum Mockers debut Swear It’s True and the band even did a live album, Caught In The Act, the same year.

“There was quite a bit of rivalry between The Dance Exponents and The Mockers in those days. The Dance Exponents had the biggest album in 1983 with Prayers Be Answered which we also recorded. So we were running a dual role, selling studio time to keep us alive and most of the Mandrill and Reaction recording was done in the wee small hours after we tried to make a living during the daytime.”

Other recordings done at the studio in the 1980s included debut albums by Dave McArtney and the Pink Flamingos, Coup D’Etat, Coconut Rough, Peking Man and Carl Doy’s Piano By Candlelight.

“The best production was Dave Dobbyn’s Loyal album produced by Mark Moffatt from Australia,” recalled Tucker. “I thought Dave was brilliant, his songs were brilliant, his singing was brilliant and the production was right up there.”

“I quit doing anything with Reaction in 1987, due to the situation at radio. I’d run out of steam. I no longer wanted to work all day and all night. Between 1975 and 1985 the airplay graph got progressively worse and I am sure the music got better. Right through the 80s the phrase was “we play the hits” so if you didn’t have a hit you couldn’t get your song played. It was very anti-local because it was hard to break anything. No radio station wanted to take any risk.”

In 1988 Mandrill was the first studio to put in a digital recording system – 8-track English AMS gear – into their commercial studio. They had a lot of trouble with the system and their first foray into digital proved to be premature. The studio’s second digital attempt in 1991 was a winner when they installed a New England designed Bosch 16-track Synclavier. “We used that for some music productions,” said Tucker, “in conjunction with the 24 track.”

By the 90s, Tucker was facing the fact that, “all the expensive equipment was in the big music studio but most of the income was from the small studio. In 1993 we closed the music studio in favour of doing only post-production audio. I could see the future of music was going to home studios using computer-based equipment.”

A new “York Street Studio” opened across the road in 1992 with a focus almost entirely on music and they purchased Mandrill’s 24-track tape machine.

Tucker sold the Mandrill business to Video Images in 1995 and moved into importing hi-fi and home theatre speakers and audio gear.

The York St Mandrill Studio site gained another music tenant when the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand (RIANZ) took over the premises as their head office in 1997 and stayed there until they moved to Hakanoa Street in February 2006. RIANZ changed their name to Recorded Music NZ in June 2013.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air