The diary entries and King’s discography provide insight into just how busy the local music scene was back in the 1960s and 70s, a time when local recording artistes were featured on radio and television as well as on major tours as a matter of course. King’s diaries note that his work didn’t just cover recording sessions, but also tours and live shows as well as TV programmes featuring live music.

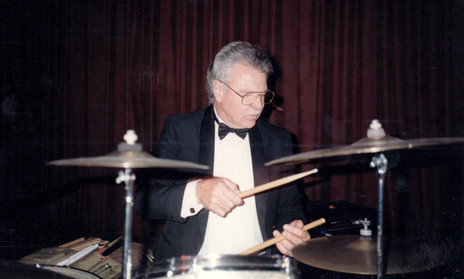

An engineer by training and a drummer because he really had little choice (either you is or you ain’t), his career at the drums, both live and in recording or TV studio, has lasted over half a century and he isn’t slowing down just yet. Why would he? King believes he is playing better now than ever.

This is not a “life history” – time for that later, perhaps, when he has decided to retire. This is an acknowledgement of his massive contribution to our country’s music legacy. King is, like many drummers, a remarkably self-effacing chap. He is also the “go to” guy for drummers whose gear needs repairing or those who are in need of impossible-to-find replacement bits for a favoured vintage kit.

Born and raised in Auckland, King’s fascination with the drums was ignited in the mid-1950s while on holiday with his family in Rotorua. He saw Brian Spence, drummer with a swing big band at Rotorua’s Soundshell, perform the classic drum solo tune of the era, ‘Golden Wedding’. Mesmerised by what he saw and heard that evening, there was no doubt in his mind about what he’d be doing for the rest of his life.

“I was about 12,” King told Chris Bourke in a 2011 RNZ Musical Chairs interview. “The drum solo made my jaw drop, and I thought that’s what I wanted to do. I had a second cousin who played drums in Auckland with The Hulawaiians – Jim McLeod. He was instrumental in getting me started.

“I started listening to the radio and then Rock Around The Clock came out. I saw the movie 12 times, to try and learn and see what the drummer was doing. From that, my mum told me there were bands in Auckland on Saturday nights. I’d go into the radio theatre at 1ZB and watch the radio bands. I’d pester the drummers – who were Don Branch, Barry Simpson, Frank Gibson Sr, Brian Spence, Lachie Jamieson – and they answered every question and fed me with information, so I went home and practised.”

“THE DRUM SOLO MADE MY JAW DROP, AND I THOUGHT THAT’S WHAT I WANTED TO DO.” – BRUCE KING

In 1957 he joined a band called The Swingsters, playing social dances and 21sts. One of his treasured possessions is an acetate of his band at a talent quest at the Māori Community Centre. “I’d only been playing drums three months. The drum solo is probably better than anything I do today,” he said in 2011. “It had form and construction, which I enjoy listening to now, rough as it may be, but it is me at 13 and fresh.”

Attending Avondale College, he played in a band called The SwingKings made up of pupils from the College, where he was promised a new drum kit if he passed School Certificate.

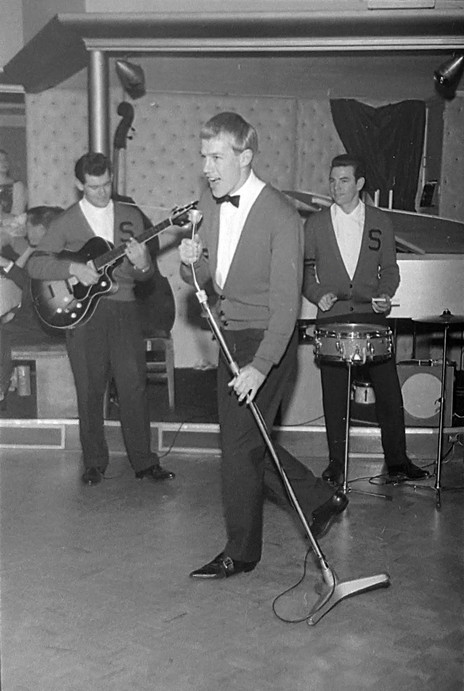

He met Graeme (Gray) Bartlett at the Mt Albert teenage club and the two became part of Clyde Scott’s backing band. They recorded Scott’s cult rock’n’roll track ‘Gravedigger’s Rock’ at Bruce Barton’s studio in the Pacific Buildings in Wellesley Street before becoming Clyde Scott & The Senators and undertaking a two-and-a-half year Saturday night residency at Bob Sell’s Colony Nightclub. The floor show began at midnight and there they backed local acts including Kiri Te Kanawa and Kahu Pineaha.

From his first recording in 1957 through to 1974, he played on dozens of recordings a year. That’s him drumming on some of the most recognised pop hits ever recorded in New Zealand: Allison Durbin’s ‘I Have Loved Me A Man’, a No.1 hit, and Bunny Walters’ ‘Brandy’ and ‘Take The Money And Run’, both charting in the top 10. He also played on The Chicks’ hit cover of ‘River Deep, Mountain High’ in 1968, and the Howard Morrison version of ‘How Great Thou Art’ from the Royal Variety Show in 1981.

While still an apprentice in 1961 and 1962, King took time off work to hit the road with Harry M Miller’s Showtime Spectaculars.

“Fortunately for me it put the deposit on my house. I was newly married, left a pregnant wife at home and went out on the road,” he said. “My boss was lenient for the first two years. Then he said, ‘I would like you to put a little more effort into your apprenticeship rather than music.’” At its completion, he was offered a tour of Australasia as part of The Mike Perjanik Band, and turned professional.

By the early 1970s, King was entrenched enough in the pop music world to stand up for what he believed best suited a song, although it nearly got him fired from the ‘Brandy’ sessions after a run-in with Midas-touch producer Peter Dawkins. “He wanted me to take all the bottom heads off my drums to have what was called a concert tom sound, and I refused,” King said. “I wanted my sound, which was a double head.” Dawkins backed down and the song was a No.4 hit in April 1972.

The list of sessions and releases is extensive and includes cutting sides for singers Vince Callaher, Toni Williams, Ricky May, Bill & Boyd, Lou and Simon, The Chicks, Tommy Adderley, Ken Lemon, Gerry Merito, Dinah Lee, Lew Pryme, Maria Dallas, and Ray Columbus. His output includes dozens of singles, and masses of EPs and LPs. There have also been numerous compilation CDs released in recent years, and a full discography is being compiled for later inclusion.

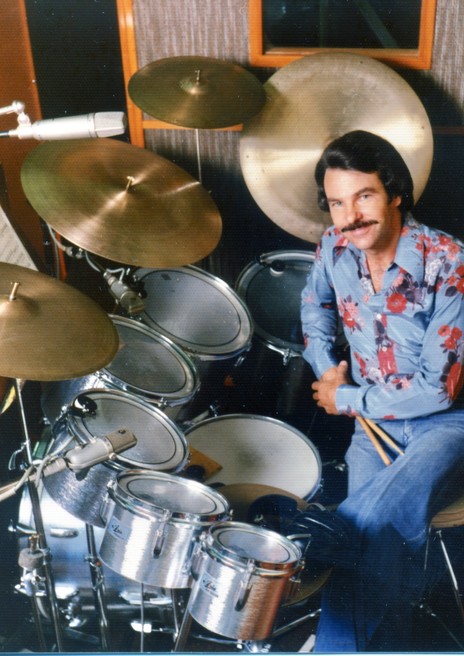

Recording at any number of Auckland studios – from Peach Wemyss Astor, through Mascot’s two moves, to Eldred Stebbing’s premises firstly under his house and then on Jervois Road – King kept a kit at each studio. “I bought a motorbike and I just used to put a bag of cymbals on the back and ride around the studios each day,” he told Chris Bourke. “Because we were doing television sessions, we were doing records, we were doing jingles in all these different studios every day, and it was a great way of getting around.

King performed in over 300 TV programmes between 1959 and 1999.

“The association with television helped [in recording singles/albums] because the arrangers for television, who were Bernie Allen, Tony Baker, Wayne Senior … Because we were good at what we did in the studio, the orchestra became so efficient recording television, economically it was sensible to use the same studio musicians to do a lot of their work. So I was used on most of the sessions for most of the singers who performed on television. When they came to do their records, we were asked to do them as well.”

Besides the records he features on, King appeared in and performed on over 300 TV programmes including many series (a series usually being between seven and 13 shows) and specials (usually one to two shows) between 1959/60 and 1999.

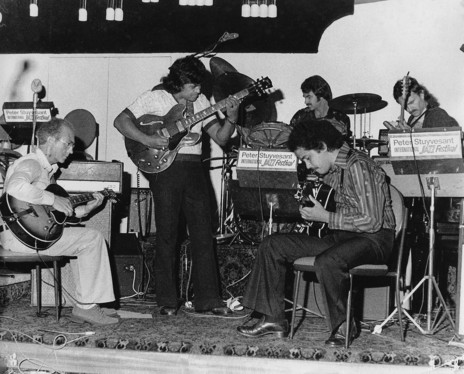

In many of these shows he was visible – as in the Radio Times series with Billy T. James, The Ray Woolf Show, the Just Jazz series with the Bart Stokes Big Band, Jazz Scene with the Auckland Neophonic Orchestra, 10 years with the Christmas in the Park series, while in others the band was not featured on screen. Again, a full listing of television shows is being compiled.

Of course, the flip side of being a session player is the live work, and King has had his share of the big gigs. He has played behind some of the biggest names in show business: Dame Shirley Bassey, who hired him for four tours, Harry Secombe, Helen Shapiro, Herb Ellis/Barney Kessel, Georgie Fame, The Coasters, The Drifters, Thijs van Leer, Jackie Trent and Tony Hatch, Roger Whittaker, Roy Phillips, Gene Pitney, Jimmy Webb, and dozens of New Zealand’s best.

Radio Times opened the door to national stardom for Billy T. James, but King had earlier toured the pubs and clubs of the North Island in a Thunderbird with the hard-partying James, Tuhi Timoti and Allan Wade. More often than not, the responsible Bruce King assumed the role of driver for the trip back to Auckland.

He also spent time in the pit playing for huge shows such as Cats (New Zealand cast, six months) Evita, Annie, West Side Story, Les Misérables, and Anything Goes (Australian cast). He has been a regular on the Norfolk Island Jazz Festival and their country music festival for the past 21 years.

In his career, King has seen and been a part of astonishing advances in recording technology and drum technology. From early 78 rpm pressings on brittle shellac through to CDs and other forms of digital recording, from – by today’s standards – fairly primitive drum sets, to custom-built works of percussive art, it’s been a journey he has relished and appreciated every day.

He’s been able to sustain his love of drums and drumming and succeeded in making music his “real job”, combining it with his engineering skills to provide a much needed tech service to the drumming community. Along the way, he has played no small part in contributing to the soundtrack of our lives through several generations.