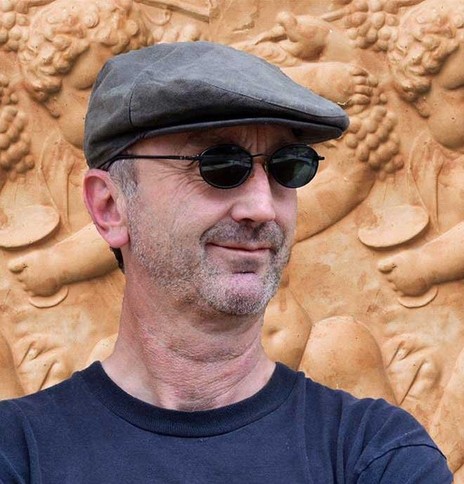

For a kid whose ambitions were to sing in a band, Dunedin-born Andrew McLennan found himself exactly at the right place and time. He was living just down the road from Westlake Boys High on Auckland’s North Shore, a school where a serendipitous meeting of like minds was about to take place.

His wider circle of schoolmates included Richard Von Sturmer, Don McGlashan (“I was so in awe of his musical gifts that I felt very shy around him”), Mark Bell, Ian Gilroy, Peter Warren, Rob Guy and Tim Mahon.

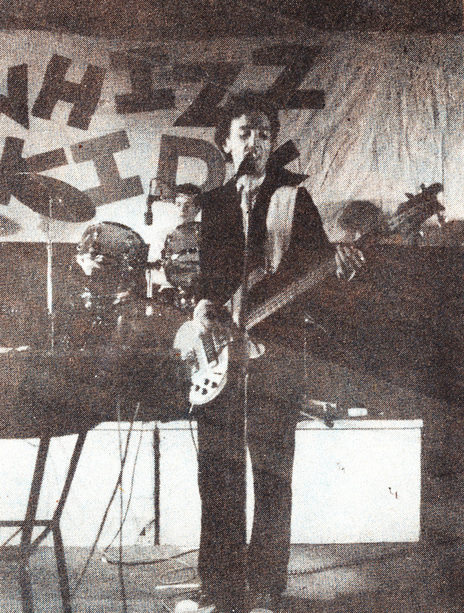

Bell, Mahon, Gilroy and McLennan formed a band called Titusucanbe which they later renamed The Whizz Kids. The Whizz Kids were a Petri dish, a nurturing ground that mentored a group of young musicians who later contributed to some of that generation’s most exciting music – Blam Blam Blam, The Crocodiles, The Plague, Pop Mechanix, Lip Service, Coconut Rough and The Swingers.

For Andrew it was straight out of school and straight into fulltime music. Between 1978 and 1980 he fronted both The Whizz Kids and The Plague, played some keyboards and wrote some of the songs. The Whizz Kids were power pop; The Plague were art rock theatre anarchy.

Members of The Plague were known by the surname Snoid, Hence Andrew Snoid.

The Plague seems a strange contrast to Andrew’s mainstream pop ambitions, but he explains it was because of school mate (poet and screenwriter) Richard Von Sturmer. “Being involved with anything he had a hand in was always something special.” Members of The Plague were known by the surname Snoid, which is why McLennan is often referred to as Andrew Snoid.

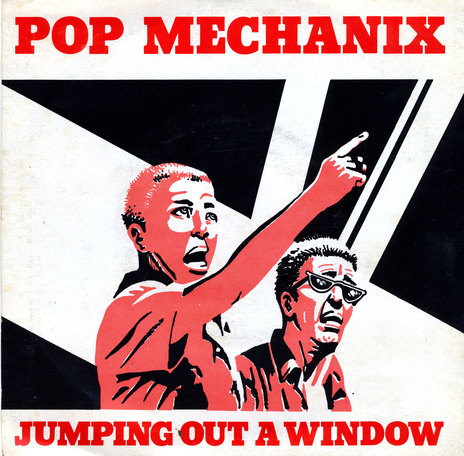

In 1980 Andrew joined one of the nation’s top touring acts, the Australia-bound Pop Mechanix, replacing their long time vocalist and founding member Dick Driver. Playing support slots for Split Enz, The Stray Cats, Joe Cocker and Eric Burdon, the band were building a solid reputation and playing to ever increasing crowds when Armageddon hit.

A Sydney outfit called Popular Mechanics claimed a conflict of interest and approached the band’s label, CBS Records, asking for $5000 in return for relinquishing all rights to the name. The record company refused and a protracted court case followed, severely denting the band’s momentum. The judge ruled in favour of Popular Mechanics and Pop Mechanix lost the right to use their name in all territories except in New Zealand, Canberra and the Northern Territory.

Andrew: “CBS could have paid the cash but didn’t, they were not going to be pushed around by a small-time band that had only released one independent single. It was all about the label’s arrogance and it fucked us.”

Tim Murdoch of Warner NZ later reclaimed the rights to the name and gave them back to McLennan.

The band soldiered on as NZ Pop then The Zoo, eventually returning to New Zealand to continue as Pop Mechanix. For Andrew it was all over and feeling somewhat disenchanted by the experience he accepted an offer to join The Swingers.

Andrew had played with The Swingers a year earlier at the XS Café in Auckland, taking on vocals for a cover of the Suburban Reptiles track ‘Saturday Night Stay At Home’. “When Phil Judd called me a year later and asked me to join the band the chance to work with him was too appealing but I did feel like a rat jumping a sinking ship as far the Mechanix were concerned.”

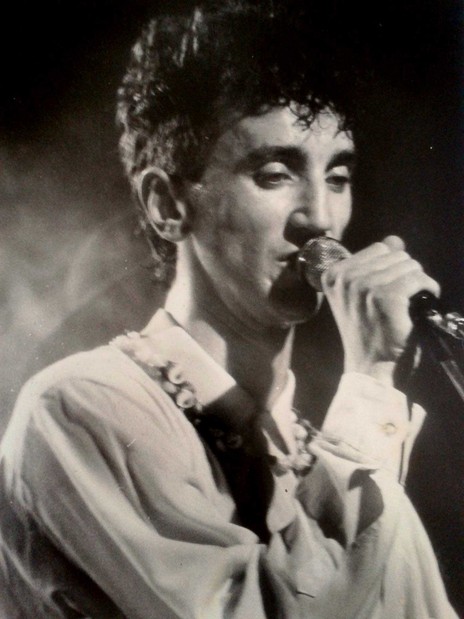

The Swingers were faltering under the weight of their mega-hit ‘Counting The Beat’, a song that had become so all-consuming it had stopped the band from moving forward. Judd’s solution to this dilemma was to recreate the band. In 1982 Andrew took over lead vocal duties from Judd, taking some of the weight off his shoulders and allowing him to concentrate on the guitar, but it was to no avail. Andrew: “The Australian audience didn’t get The Swingers and ‘Counting The Beat’ was all they wanted to hear. It was soul-destroying.”

Despite everyone’s best efforts the band was playing to ever-diminishing crowds and losing money. Finally, Judd pulled the plug but it wasn’t all a loss as Andrew explains: “Working with Phil was an accelerated learning curve. I got to work with a musical genius who taught me simple things like routine and discipline. His attitude was awe-inspiring. He would start off every day with writing then we would learn new songs and when the rehearsals were done we would spend the rest of the day doing bonding stuff like playing baseball. Phil taught me how to run and manage a band and apply a workmanlike attitude to the creative process.”

‘Sierra Leone’ “gave me my 17 minutes of fame but became this albatross I couldn’t get past.”

With the end of The Swingers, Andrew returned to New Zealand in 1983. He took what he had learned from Judd and applied it to his next project, Coconut Rough. He sat down and wrote 22 songs, some of which were demoed at Mandrill, and then shopped them around.

The response was positive, especially towards a track called ‘Sierra Leone’. After working through a few offers the band signed with Mushroom. Andrew remembers taking a call from Mushroom boss Michael Gudinski who expressed his feelings on ‘Sierra Leone’ with a hearty “Maaaaaate!!”

The song was released and went top five in New Zealand and top 50 in Australia. “The irony of it was that the one hit wonder thing that affected The Swingers so badly became our yoke to bear as well. ‘Sierra Leone’ became the only song from our repertoire that people wanted to hear and no matter what we did we couldn’t follow it up.

“I was 22 years old and that song was everywhere. It sure as hell gave me my seventeen-and-a-half minutes of fame but it also became this albatross I couldn’t get past. For a long time I struggled with it. I don’t feel that way now because it’s grown beyond me and I am really grateful for the royalty cheques, they never cease to amaze me.”

Coconut Rough eventually imploded, partly due to the weight of ‘Sierra Leone’, and in 1986 Andrew rejoined Pop Mechanix for “three years of productive and well-paid work”. But when the band decided to relocate to Christchurch to take up a long-term residency Andrew didn’t want to make that journey and bowed out. Instead he took up an offer from Tim Murdoch of Warner NZ, who paid him to go Los Angeles and write songs with producer John Boylan (Sharon O’Neill, The Little River Band, Boston). He spent 1990 through 1991 living at Boylan’s Laurel Canyon home and studio.

“I wrote and recorded all day most days but I was not confident about what I was doing and on top of that I was missing home. I was a bit despondent and escaped as much as I could and explored the city by car. I discovered these specialist vintage toy shops and started buying up bits and pieces and I began to think this was something I could do.”

Packing up the toys he had collected, he returned home and in 1993 opened The Old Tin Toy Shop in Parnell Village, Auckland, a retail and Internet operation that became a money-making machine and paid for a heady lifestyle that included plenty of partying. Between 1995 and 2000 Andrew kept making music, performing on and off with a cappella group The John Does, (Peter Elliott, Jay Laga’aia and Nathaniel Lees).

It all started coming apart in late 2005 when Andrew purchased a noted collection of Disney memorabilia in San Diego. The purchase required a hefty bank loan. He realised the collection was not going to be as easy to sell as he thought and with numerous other deals to maintain he began to feel the pinch and started losing his grip. In 2007 he walked away from the business, narrowly avoiding bankruptcy.

One person who helped in this period was Kevin Findlater (Bulldogs Allstar Goodtime Band, Hogsnort Rupert, Dave and the Dynamos) who was now working as a mentor. He urged Andrew to start writing again, “saying that through music I would find myself again. I don’t like admitting it, but he was right!”

“I HAVE BEEN AWAY SO LONG THAT IT IS NOT A COMEBACK, IT IS A BEGINNING.”

In 2010, Andrew picked up the guitar and wrote ‘Cabin Fever’, the first of 25 new songs, 12 of which were recorded at Findlater’s home studio for Andrew’s debut solo album Hiding In Public. Between writing and recording, he kept himself busy with live work.

Andrew McLennan is intelligent, thoughtful and no longer ambitious in the way he once was. These days it’s all about the craft and enjoying the moment. “I have been away so long,” he says, “that it is not a comeback, it is a beginning.”

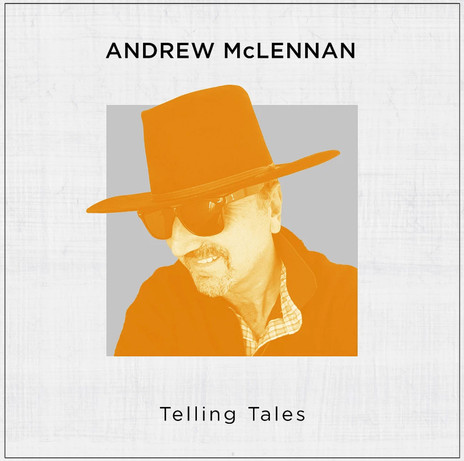

In 2018, Andrew released the album Telling Tales.