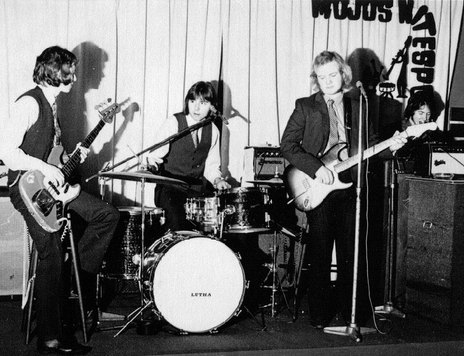

Its two frontmen and songwriters were poles apart vocally, but knitted together harmonically. Leonine rock’n’roller Garry McAlpine, writing with Gordon Spittle, presented songs at the heavier end of the rock spectrum in full vocal power, while Graham Wardrop contributed lighter, lyrical material, singing lead or harmonies in a pure, vibrato-free tenor.

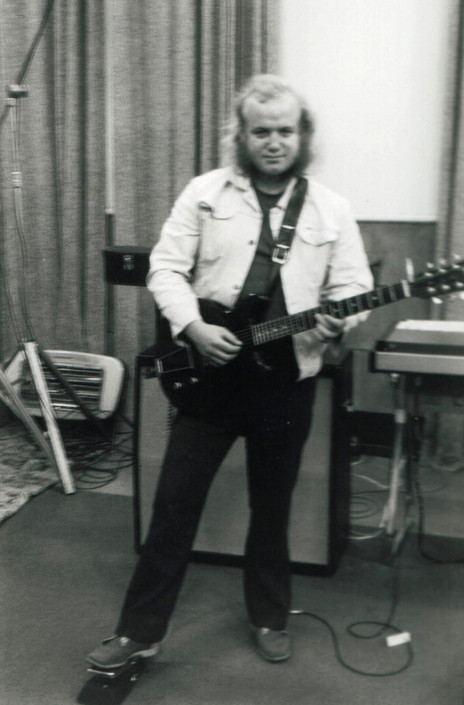

Wardrop had been playing bass with power-rock trio Kaleidoscope, but joined Lutha as electric guitarist. He was a quick study. In a previous AudioCulture story he told Spittle: “I taught myself acoustic guitar and then developed an increasing bent for songs as art after studying John Lennon's ‘In My Life’ as a poem for School Certificate exams. When Big Pete asked if I would play guitar in a new band with them – and I had never played electric guitar – I was over the moon. I listened to [McAlpine’s former band] Pussyfoot at courtyard parties and university gigs and was blown away with Garry’s vocals.”

Wardrop was a finalist in the Studio One television songwriting competition for his song, ‘I Really Only Want to be With You’.

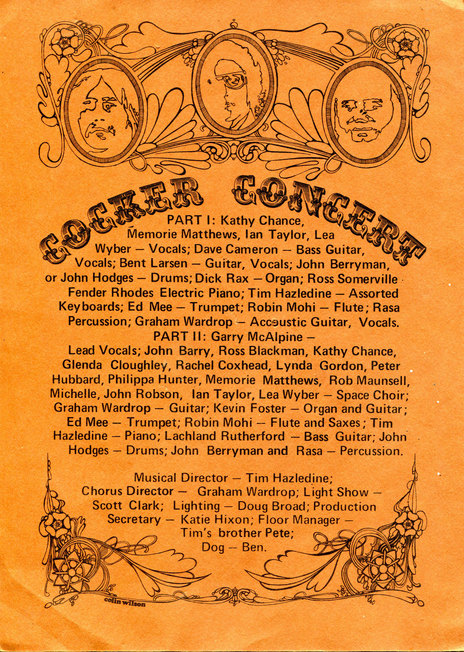

Despite Lutha’s brief but potent 1971-73 lifespan with this lineup, the band was influential, producing two albums, Lutha and Earth, which are still gaining traction for collectors as far afield as Germany. It also sprung a couple of singles that garnered a lot of airplay – ‘Then I Saw Her Face’ and ‘Stop: The Music is Over’ – and Wardrop was a finalist in the Studio One television songwriting competition for his song, ‘I Really Only Want to be With You’.

Before Lutha, Wardrop had been active musically at Otago University (where he was meant to be studying accountancy and economics), writing music for and performing in capping concerts, playing at university arts festivals, in various bands, at folk club events and so on.

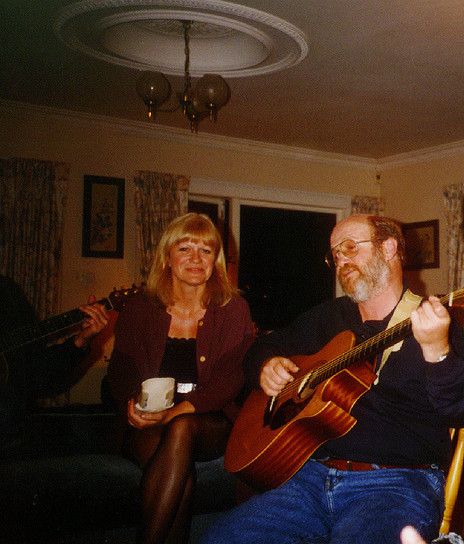

I should disclose here that he and I are longtime friends, having met 40-plus years ago when we were performing at the university arts festival in Dunedin. Wardrop was part of the Otago University contingent and I, Canterbury. We still perform together occasionally and enjoy it immensely when we do, although our paths have diverged increasingly as I disappeared further down the rabbit holes of print journalism and he continued in music.

The Beatles have been and still are a major influence for him, along with Paul Simon, James Taylor, David Crosby, and others of that ilk who write thoughtful, creative lyrics, interesting melodic lines and chordal structures on a crisp, rhythmic framework. And as much as he enjoyed playing with Lutha, his love of acoustic music and the sound of the voice with unamplified six-string was stronger.

By 1973, his time in Lutha had run its course. University also lost out. His economics professor had suggested that as an economist he’d make a great guitarist, and the words stuck. That year he left New Zealand to see what musical opportunities might open for him across the Tasman.

Australia was a difficult road initially, but soon he was working solo and with others, booked in backup bands for live shows and television, writing charts and doing session work. His songwriting was also prolific in these years. He had married, and he and wife Fay had two young children. They lived in various places on Sydney’s beautiful northern beaches on the Barrenjoey Peninsula, a surfing mecca and vacation hotspot where the laidback lifestyle was a drawcard for creatives of all genres.

Wardrop entered a rich period of performance when he was asked to join the Anne Kirkpatrick Band. Anne is the daughter of the late, legendary Outback balladeer, David Gordon Kirkpatrick – far better known as Slim Dusty. And while country music might have seemed left field from Wardrop’s rock roots or his acoustic preferences, he is nothing if not versatile, and the chance to work with the other fine musicians backing up both Anne and Slim’s bands was not something he could pass up.

For several years he toured Australia with the Slim Dusty caravan, playing in both bands and seeing parts of Australia out beyond the black stump, as they say, that even many Australians don’t get to.

“We did a big horseshoe – New South Wales, west of Queensland and as far as Cairns, right around Adelaide,” he says. “We flew across the desert to Perth, up the coast and a whole lot of tiny little towns inland that other artists probably just drove straight through onto the next big place. Slim had a real connection with down-home Australian people and they loved him for it.”

Wardrop had been noncommittal initially when Slim had invited him to join the band, wondering if he wanted to play three-chord backup to songs such as Slim’s No.1 hit by Gordon Parsons, ‘A Pub With No Beer’.

“I was working in Anne’s band with Jimmy Duke-Yonge [drums] and Bill Graham [bass], and they said, ‘You don’t know who this guy is, he’s an icon! We’re going to do it, because it’s going to be great, and if you want to keep playing with us, you’d better come with us!’ So I said Okay, I will.

The Slim Dusty Show featured a variety of performers with Slim as headliner, Anne’s band, brother David, Slim’s songwriter wife Joy McKean and sister Heather performing as the McKean Sisters, plus a guest artist or two.

“I never regretted it for a single moment,” says Wardrop. “We had a fantastic band, playing that very straight, very technically simple music, but what you had to do with Slim was develop the feel. It wasn’t about playing lots of notes or being impressive technically. That was what Slim was about. He never said he was a musician. He said, ‘I’m a balladeer and I surround myself with fine musicians.’ He was always totally himself and gave the band room to move within that genre.”

Even so, there were the occasional musical differences:

“I was musical-directing an album for him in Sydney, the first one I’d musically directed, and we were in the control room. Slim tuned up his guitar and said, ‘Right, that’s good’. I said to him, ‘Excuse me, Slim, I feel I have to say this, because otherwise I’m not doing my job, but your B string is flat.’ He looked at me with a little smile and said, ‘Graham, it’s Okay. It’s been like that for 40 years. I like it that way.’ ”

By 1984, Wardrop was ready to move the family back to Christchurch. He had grown up in a close musical family, with artist-musician sister Radha (the founder of Universal Children’s Audio), mother Eva a shy but tuneful singer, and father Bill an excellent, if not professional musician and member of the Canterbury Plainsman Barbershop Chorus well into his later years. Wardrop wanted to be closer to his family and needed to focus on his solo career.

He has travelled the length of New Zealand many times over, performing in festivals, folk clubs, house concerts, and on huge concert stages.

In the span of years since then, he has travelled the length of New Zealand many times over, performing in festivals, folk clubs, house concerts, and on huge concert stages. He has opened for Manhattan Transfer, Vanessa Mae and several other internationals, and has been a guest artist in countless festivals, from the Waiheke Island International Jazz Festival down to the Queenstown Jazz Festival and all points between.

He produces albums for himself and others, and builds most of the instruments he performs on. But composing, songwriting and finger-style guitar playing, for which he is heralded, are at the heart of it all. A particular highlight for him was sharing the stage with Tommy Emmanuel, Michael Fix and Martin Taylor in a Gray Bartlett-organised guitar festival.

Wardrop’s working life has taken him from Denmark to Britain, from Wagga Wagga to Mapua, Hong Kong, Canada and the Papua New Guinea highlands. Over nine Canadian tours, he counts more than 150 shows with Canada’s well-beloved songman, Valdy, and together or separately they have played festivals and concerts countrywide, either as the featured act or opening for the likes of Buffy Sainte-Marie and David Clayton Thomas, of Blood Sweat & Tears.

He’s lost count of the number of times he has performed in Hong Kong since first working there in 1996, and was often going up two or three times a year to play at the Hong Kong Country Club. He played solo gigs over the holiday season, then musically directed the New Year’s Eve shows with feature artists such as Suzanne Lynch (née Donaldson, ex-Chicks) and Sydney-based Kiwi singer Jo Elms. He also did folk club tours of Britain in 2011 and 2012, going from place to place by train, feeling lonely, and trying to evict the words of ‘Homeward Bound’ from his brain, but he rates his 17-odd tours to Papua New Guinea as altogether more interesting.

Organised and hosted by businessman Graham Wheatley, his work in PNG has comprised outdoor concerts and performances at conferences. Security is ultra-tight wherever they go, where expatriates and their guests live in apartment blocks within razor-fenced compounds watched over by heavily armed guards.

While there, Wardrop has been taken to singsings in remote villages and done fundraising concerts for AIDS education and to raise money for a hospital in the highlands. He makes a point of playing in schools. “The kids there really love music and guitars, and don’t have the money to buy guitars. I try and give something while I’m up there, rather than just going there to make money.”

On several occasions he has taken Christchurch pianist and vocalist Liz Braggins with him on these tours.

“Liz and I were over in Kimby Bay to play at a resort on the Sea of Bismarck, where professional photographers go to do underwater photography. It’s exceptional for diving,” he says. “We were playing in a hauswin, which is a roof with no walls, so the breeze blows through to keep you cool. We were playing to clients for a conference and all these villagers came over and stood outside to watch. I remember playing ‘Commuting’ [which uses delay pedals and other effects] and the looks on their faces – they could not believe it. We shook hands with them after and said hello to the kids. There are incredible moments like that in the more remote parts where the Nationals, the local people, know of guitars, but they’ve got this old thing with three strings from a piano or something. So seeing a professional act, they are quite astounded.”

One of his most demanding gigs was playing at the Bomana prison, just out of Port Moresby. “It’s the biggest jail in PNG. I’m the only person who’s ever played there. No-one has done it before and no-one’s done it since. It was recorded for EMTV and broadcast nationally several times. It was a scary gig, playing to inmates who are pretty violent – it’s a violent place – but there was good security and at the end of the gig about 50 prisoners lined up to shake my hand or hug me. That was something I’ll always remember.”

He has also been flown far into the interior to Tabulbul, an isolated village servicing the Ok Tedi Mine, to play for the chairman of the golf course. Only celebrated Australian trumpeter James Morrison had done this before him. “It’s about 500km inland and is the furthest, most remote place I’ve played at, close to the Irian Jaya border, and too dangerous to go outside the walls.”

His last PNG tour in 2016 coincided with civil unrest, when angry demonstrations against corruption in politics erupted and Port Moresby, the capital, was closed down. “It affected my crowds pretty badly and it wasn’t the happiest trip I’ve had.”

Wardrop spent most of 2016 on the road while his house was being rebuilt after damaged sustained in the Christchurch earthquakes. He toured New Zealand over this gypsy year, holidayed in Australia, and spent two months in Canada playing in various festivals, including the Salt Spring Island Music & Garlic Festival, with its eccentric melange of roots music and root stock.

Graham Wardrop is a low-key high achiever, flying under the mainstream radar because his shtick is not on the commercial wavelength.

Despite having been in the public eye for a long time, Graham Wardrop is a low-key high achiever, flying under the mainstream radar because his shtick is not on the commercial wavelength. And that’s the way he likes it. He is his own man, doing his own thing. Throughout the various strands of his working life, it’s the music urging him on, doing the very best he can and never short-changing: “For my own satisfaction, I have to play to the best of my level, no matter who I’m playing for.”

Over almost five decades as a performing musician, he has been both feted and ignored, and unlike other more straightforward careers, which are often linear and progressive, the pendulum continues to swing back and forth, back and forth. However, more frequently he is asked to perform at noteworthy concerts, such as soloing with the Auckland Philharmonia or the Christchurch Symphony, which he has done several times. (“It’s fantastic, but I don’t find it easy. Being a soloist with an orchestra really puts the pressure on.”)

He has been commissioned to play for millionaire businessmen and played background music in a pub. He’s done gigs at the Christchurch Casino, stopping dutifully every couple of minutes for the Keno results, and musically directed large outdoor public concerts. He’s performed for children, for the elderly, and has been a journeyman muso, playing with or accompanying others, working with some of the best in the land. He was also honoured to play at the funeral of friend and fine musician Murray Wood, the CEO of CTV, after Murray lost his life in the Christchurch earthquakes.

Among Wardrop’s career highlights he cites playing a New Year’s Eve concert on the steps of the Sydney Opera House with the Anne Kirkpatrick Band in front of 200,000 people (c1979); playing at last year’s Waiheke Island International Jazz Festival as the only soloist and getting a standing ovation; and simply performing with close musician friends at house concerts and the like.

He was an inductee of the Rockonz Hall of Fame in 2010, honouring Canterbury musicians, but his work speaks for itself. Whether writing music, playing guitar, recording, arranging, building guitars and performing solo or in groups, focus and diversity underline his long career. It’s a 3D portrait – sometimes in technicolour, sometimes in faded black-and-white – of a full-time working musician.

“At this stage of my life I feel incredibly privileged to have worked with so many wonderful people in such a variety of areas, and I couldn’t be more blessed as a musician. I’m a pretty lucky guy.”