In early 1863, on the eve of the Waikato War, Ngāti Whātua chief Paora Tūhaere purchased the schooner Victoria for £1,400 and set off with 20 of his people for Rarotonga to develop a Māori trade with the islands of the South Pacific. That trade led to exchanges not just of produce but of people, with periodic voyages and marriages reinforcing ancestral links.

It is fitting then that more than a century later a band that forged a new synthesis of Māori and Pacific sounds, mixed in with a Polynesian adaptation of Jamaican reggae, should be so identified with Tūhaere’s Ōrākei base.

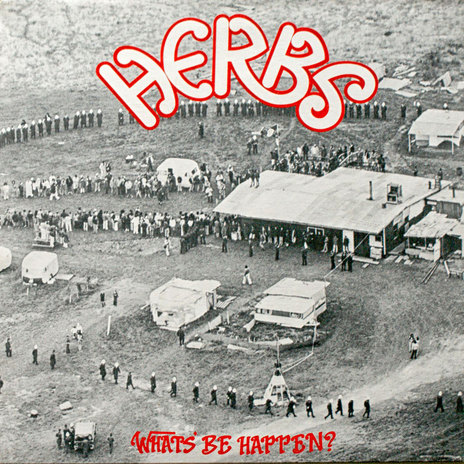

Whats' Be Happen? the landmark 1981 mini-LP from Herbs, issued just prior to that year's Springbok Tour. The sleeve featured an image of the police action to clear Bastion Point in May, 1978.

Herbs grew out of Backyard: Toni Fonoti, Spencer Fusimalohi and Fred Faleauto playing in the back bar of the Trident Tavern in Onehunga.

Will ‘Ilolahia was Fusimalohi’s cousin and he knew Fonoti from the Polynesian Panthers. When they asked ‘Ilolahia for a hand he went down to have a listen. “It was like that scene in The Blues Brothers where the band is playing behind chicken wire,” he says. “There were fights and jugs flying.” At the time he was managing Papa, a band with connections to Bastion Point through Dilworth Karaka and Alec Hawke, the younger brother of Ngāti Whātua campaigner Joe Hawke.

‘Ilolahia agreed to come on as manager, adding Karaka to the line-up for background vocals and guitar strum, and Backyard became Herbs.

Fonoti says his vision for the ideal band was himself as the Samoan, plus a Tongan, a Rarotongan, a Māori and a Pākehā. The later addition of Phil Toms created that dream band for the recording of its debut mini LP, Whats’ Be Happen?

‘Ilolahia set out three goals: the band should play original music; it should tour the Pacific; and the tour should include wives and kids.

At an early meeting, which also included lawyer/musician Ross France, ‘Ilolahia set out three goals: the band should play original music; it should tour the Pacific; and the tour should include wives and kids. By the end of 1983 that had been achieved, although with an ever-evolving line-up and a lot of gigs along the way.

‘Ilolahia took the band to Hugh Lynn, owner of Mascot Studios, who had a fledgling record label, Warrior. Lynn was also involved in touring overseas acts, which meant Herbs was able to get the support slot for the likes of Stevie Wonder (who didn’t play because a rainstorm made the stage unsafe – the support wasn’t told that), Tina Turner, Black Slate and UB40.

Bastion Point and the emerging land rights movement loomed large for the band. The cover shot of Whats’ Be Happen? was of police evicting land protesters from Takaparawhau/Bastion Point on 25 May 1978.

Band members took part in the occupation, and they also drew inspiration from, in the US, the Black Panthers and the Native American occupation of the former Alcatraz Prison, Aboriginal land rights in Australia, opposition to nuclear testing in the Pacific, and the fight against South Africa’s policy of apartheid or forced racial separation.

Whats’ Be Happen? hit the shops two months before the Springbok rugby team arrived in New Zealand on 19 July 1981 for a 56-day tour. This tour breached the 1977 Gleneagles Agreement, in which governments of Commonwealth countries unanimously agreed to discourage – and withhold support for – sporting contact or competition with teams or sportspeople from South Africa or any other country where sports were organised on the basis of race, colour or ethnic origin.

Whats’ Be Happen? was released in time to be an Auckland Māori/Pacific soundtrack for the Springbok Tour, offering songs to be sung at rallies or played when people were healing tired and bruised bodies after the midweek and weekend protests. (The EP is a companion on the front line to Wellington band Riot 111 who – in a similar piece of cross-cultural synthesis – reclaimed the haka ‘Ka Mate’ from rugby and served it up as a punk call to arms.)

The Herbs EP opens with ‘Azania (Soon Come)’, which France had brought to the band as lyrics and a melody. “We put the ground to it, adding a Pacific reggae flavour,” says Fonoti. Tough words wrapped up in sweet harmonies and a reggae off-beat became the Herbs signature.

Fonoti says he was attracted to reggae because of its ability to carry a message, but he didn’t want to just copy how it was done in Jamaica. “I wanted to bring the Pacific Ocean in. Spenz, he was born and bred Tongan and he was the top guitarist on the island.

“With Herbs, we weren’t a reggae band. We knew R&B, soul, Sam Cooke, we could play all that as well. I was also in a reggae band, Unity, with Tigi Ness, Che Fu’s father. I wrote ‘In the Ghetto’ (which turned up on the Long Ago album) for that band.”

‘Dragons and Demons’ is the first of four Fonoti songs on Whats’ Be Happen?. “I was trying to say that all fears are just internal thoughts, that they are mythical, like dragons and demons,” he says. “Negative thoughts become your dragons and demons, you need to cast them out.” While the song is seen as being about mental health, Fonoti, a lapsed Mormon, says he was also drawing a bow at the control exerted on Pacific Island life by the churches.

Also by Fonoti, the song ‘Whats’ Be Happen?’ tapped into the experience of Pacific parents who came over to Aotearoa thinking it would be a place for their children to get the best education, and then they would go home to an idyllic Pacific lifestyle. “They became slaves to hire purchase, slaves to the mortgage and so on. When they left home they didn’t think they would not go back again, and their children would not go back.”

There was also the sense of betrayal at being invited to New Zealand to fill gaps in the labour market, and then being called overstayers and deported when the economy turned down. When Herbs was forming the dawn raids were still going on: mainly Samoan or Tongan homes would be targeted in a police search for people who had overstayed their work visas. People were also picked up on the street, and if they did not have papers could be deported – including in some cases New Zealand-born Pacific Islanders and Māori.

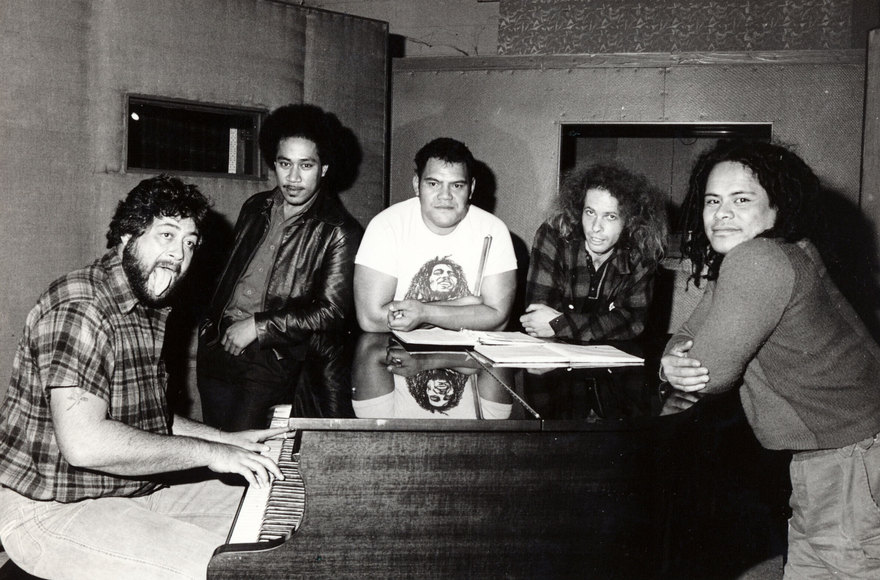

Herbs in Mascot Studios, circa 1980/81, at the time Whats' Be Happen was recorded. From left: Dilworth Karaka, Spencer Fusimalohi, Fred Faleauto, Phil Toms, Toni Fonoti.

Fonoti has never been to a Pacific island. “So when I wrote ‘French Letter’, I was imagining ‘under the coconut tree’,” he says. When his family returned to Samoa for a visit in the 1970s Fonoti was heavily into Jimi Hendrix and sporting an afro haircut. “My mother said they would throw stones at me, or think I was a fa'afafine. I would shame my family, so I could only go if I cut my hair. I didn’t go.”

Side two of Whats’ Be Happen? opens with the Phil Toms’s song ‘One Brotherhood’, in which the bass player drew parallels between the various protests:

Well they’re fighting for land in Raglan

And they’re fighting for land in Ōrākei

And they’re shouting in Parliament.

People trying to get free

On a paradise island

With the Springbok tour looming, there was also a vision of the upcoming protest:

So you knock me down

With your modunok [sic] baton

Cause I make a big noise

About the bad things goin’ on.

Modunok refers to the Monadnock PR-24 long baton issued to frontline police for the tour. In the months leading up to the Springboks’ arrival, specially chosen police squads had been practicing against Polynesians and punks at parties and pubs. So the more strategic of the protesters – such as ‘Ilolahia, an organiser of the frontline Patu Squad – knew what was likely to be coming during the tour.

Fonoti addressed police tactics directly in ‘Whistling in the Dark’, a song not about the upcoming battles but about the years of harassment of Māori and Pacific Island youth on the streets. “They’d stop you, verbally abuse you, call you a black bastard, and if you reacted, they’d arrest you,” he says. “Walking home from the pub, they’d arrest you for being idle and disorderly.

“The Polynesian Panthers raised awareness among our people that you didn’t need to get in the car, all you needed to do was give your name and address, and behave at all times in a courteous manner, don’t let them provoke you.”

‘Reggae’s Doin’ Fine’ was written when Fonoti heard of the death of Bob Marley. “We all loved Bob Marley, he clicked with us. And I was thinking, would reggae die with him? [Then I] thought no, ‘good times, good times, reggae’s doing fine.’ Like him I would use my songs as messages, compose them for our issues, not what was happening in Bob’s part of the world.”

‘French Letter’, also by Fonoti, could have been on the record, but Warrior boss Hugh Lynn insisted the 12" disc should be an EP. “I had a batch of songs that could have been worked up into a full album, but Hugh said EPs were trendy. I never saw that.”

‘French Letter’ and ‘Them’s the Breaks’ turned up on the second EP, Light of the Pacific, but Fonoti was gone by then. “I was going to stay, but they said I needed to sign a five-year contract. I was in two camps by that time – it came down to staying in Herbs or becoming a Rasta. I became a Rasta and went over to 12 Tribes. Then Willie Hona joined and it eventually became an all-Māori band, but they kept doing my songs.”

Fonoti eventually moved to Brisbane where he worked with the disabled and the homeless. He is still writing songs and stories, which he is now putting into e-books such as The Soul Effect: Opening Your Mind One Song at a Time.

By the time the Springboks arrived the band was on a tour of its own, often in the same towns where the games were being played. ‘Ilolahia remembers the band’s support of UB40 on the night of the Third Test between the All Blacks and the Springboks at Eden Park. “Ali [Campbell] and other UB40 members were at Morningside Road until someone suggested they better get out of there,” he says. ‘Ilolahia himself ended up in the police station, and got out in time to sprint up Queen Street to Mainstreet nightclub to stage manage his band, still feeling the ache of the batons.

It was UB40 who gave Herbs the tip that helped make the song ‘French Letter’ a hit, despite the refusal of radio to play a song with a title that also meant a condom. UB40 told them to find out where the chart return shops were, keep them well stocked with product, send in street people to buy some of it, then recycle until the disc took off.

Whats’ Be Happen? soon became regarded as a classic from Aotearoa (and would be reissued on vinyl in 2019, with the addition of ‘French Letter’). In retrospect, Hugh Lynn’s judgment can be seen to be right: the EP doesn’t outstay its welcome, it’s all killer, no filler – and of its time.

Just as the protest movement took on the lesson that it wasn’t only in faraway South Africa that things needed to change – racism and colonial legacies in Aotearoa and the Pacific also needed to be challenged – ‘French Letter’ became the proper centrepiece for Light of the Pacific.

‘French Letter’ also became the anthem for the next great battle, when the anti-nuclear protest fleet took to the Waitemata Harbour where Paora Tūhaere’s waka taua and schooner were once familiar sights in the 1870s.

--

1981 Springbok Tour of New Zealand