Joe Wylie was born and grew up in Levin and remembers drawing pictures in primary school including simple ‘running gag comic strips’. At secondary school he recalls competing with like-minded students drawing cartoons where, “We basically took the piss out of one another, casting each other as figures from history or superheroes.”

In 1966 Wylie left school and moved to Wellington where he studied art and design at Polytech but found much of the teaching irrelevant. When it got to industrial design they were taught that, “All that mattered was stainless steel ... and don’t frighten the chooks kind of thing.”

Early in his second year he discovered the anti-design movement coming out of Britain: “All that pre-psychedelic imagery with The Who incorporating Union Jacks and stuff. To me it was absolutely wonderful.”

Sgt. Pepper cover designer Peter Blake said something that Wylie thought sounded like a manifesto: “The only point of going to art school is to have something to rebel against.” Not long after he moved to Christchurch and started a fine arts degree at Ilam, but in retrospect, he says it was a mistake to enrol in the first place.

He had conflicts with various teachers and clearly recalls one incident. He’d brought in an ultraviolet light for a kinetic sculpture project and played around with the new fluoro colours. The teacher came in; it was dark and Wylie says, “he was like a little kid with his mouth hanging open”. But then he regained his composure and completely dismissed it, saying it was all in dreadfully bad taste.

Wylie was regularly drawing and gifting one-off cartoons to his friends for thank you's and birthdays, a habit that has lasted most of his life, but he hadn’t submitted his own work to anyone. He loved Bob Brockie’s cartoons in the anti-establishment Cock magazine and was tempted to try, but his first published work was in the Canterbury capping mag. Having discovered marijuana, he came up with an extended comic strip called “Captain Kiwi Versus The Dope Fiends”.

He demonstrated against the Vietnam War and registered as a conscientious objector. He’s proud that his mother saved his “conchie card” and he still has it.

He went to Sydney with his girlfriend Christobel and she pushed him into answering a newspaper ad for work at an animation studio.

Not long after, Bill Hanna, head of the famed Hanna-Barbera studio, visited Sydney on a talent hunt. Hanna was a hands-on boss who played saxophone and wrote songs, including the theme to The Flintstones. He saw Joe’s work and promptly hired him for their Sydney studio at around four times his previous salary.

Wylie worked on a Scooby-Doo series, where he learned professional animation. “At the time we thought the show was mildly amusing trash,” he remembered. “None of us ever believed it would become a cult show.” He also helped animate family sitcom Wait Till Your Father Gets Home — one of the only animated shows to run in prime time in the United States for more than a season, between The Flintstones and The Simpsons.

At 26 he returned to New Zealand and worked at Avalon as a studio cameraman for the NZBC.

At the end of 1974 he went to Kathmandu where for three months he lived in a house with a Tibetan artist who didn’t speak English but nevertheless showed him a completely different approach to drawing. Back in Sydney he again worked at Hanna-Barbera and on “Leisure”, an independent short by cartoonist Bruce Petty that was nominated for an Academy Award.

At 26 he returned to New Zealand and worked at Avalon as a studio cameraman for the NZBC. After 18 months he had a serious case of cabin fever but had made some lifelong friends including Bob Stenhouse, a master animator who went to the National Film Unit and later was an Academy Award nominee.

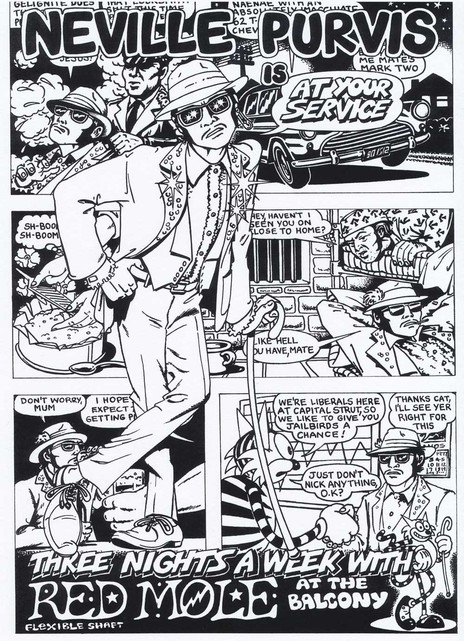

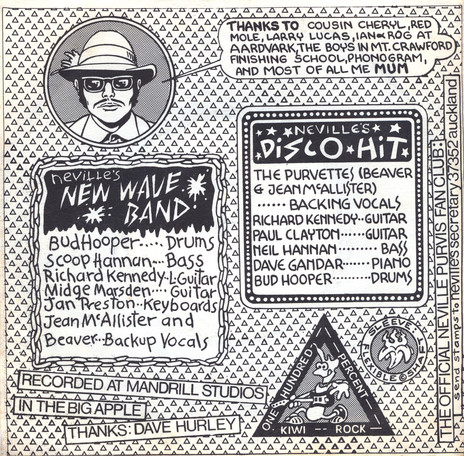

In 1977 he saw alternative theatre group Red Mole at Carmen’s Balcony and did several black and white posters for them. One, "Stairway to the Stars", is about a country girl who comes to the city to try to make it in show business. With just three horizontal panels it is storytelling at its best and marks a high point in his poster career. Typically modest, Wylie says that for him the best Red Mole posters are by his friend Barry Linton, produced after the Moles moved to Phil Warren’s Ace Of Clubs in Auckland.

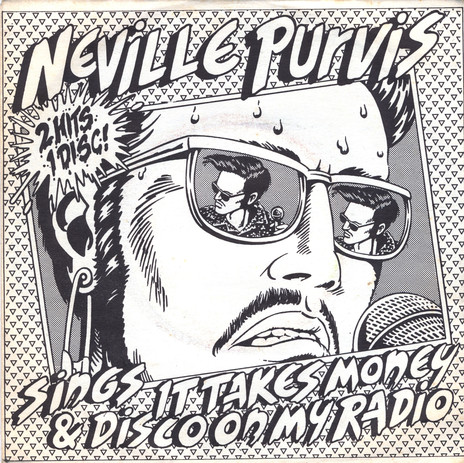

Joe also did the animated opening credits for the controversial television series The Neville Purvis Family Show. He watched it again recently and feels that “it holds up pretty well”.

He went to Auckland and founded Magic Films with Sue Wilson, employing young graphic artists on a PEP scheme to make a short film: Mãori legend, Te Rerenga Wairua. Next, with John Robertson, he did The Night Watchman (1993), a cautionary tale about the environment that started out as a Pygmalion story. In those days the Film Commission assigned an outside film maker to oversee the projects they funded. “We got a doctrinaire feminist,” he recalls, “and she decided it showed a negative portrayal of women.”

The story was revamped to one about giant insects and eco-disaster and for Wylie, seriously compromised. The Night Watchman had screenings at a number of international film festivals but Wylie, despite having sold his car and his computer to pay for the Dolby mix, has never watched it on the big screen.

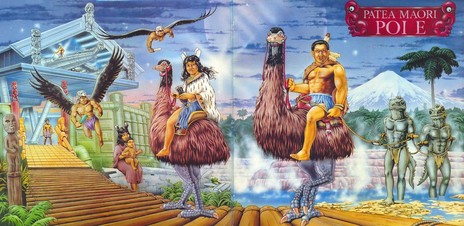

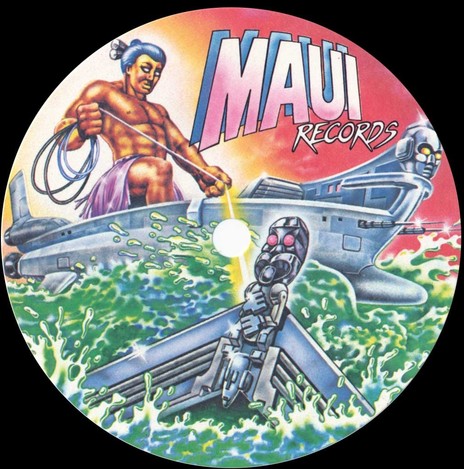

Dalvanius asked for key elements including Māori riding on the back of Moa and other images tied to the mythology of his iwi.

A happier experience was when Dalvanius Prime walked into Magic Studios and asked Joe if he would do the record cover for the Patea Māori Club’s forthcoming Poi E release. The brief was for a double album with a foldout cover. Dalvanius asked for key elements including Māori riding on the back of Moa and other images tied to the mythology of his iwi. According to Dalvanius there were flying Moa that could carry people and back in the day they ran a shuttle service operating around Taranaki. Prime then disappeared to Djakarta for a three-month engagement but when he returned there were a string of changes required. Wylie didn’t mind this. As he says, “Dalvanius was an inspiring bugger to be around and I busted a gut to get it done right.”

He remembers a great event at the end of the album tour when they had a big luncheon in an Auckland Chinese restaurant. Dalvanius had gold silver and platinum records made up using the label artwork he’d created. “Everyone got one, even the tour bus driver.”

All the hard work was worth it. The cover image has become iconic, Joe won the Tui for Best Album Cover and it later featured in a Te Papa exhibition of New Zealand music. However, Joe was surprised to discover that Dalvanius had conferred honorary Mãori status on him by crediting him in the exhibition as “Hohepa Wylie”.

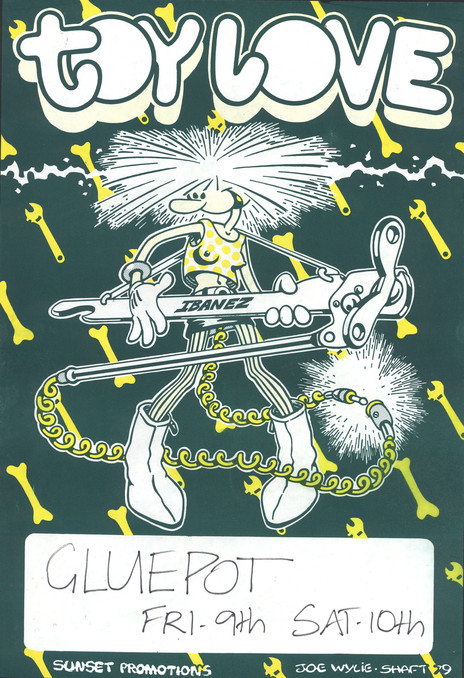

When he first came to Auckland his friends told him he had to see a band that had come up from Dunedin. He finally caught Toy Love at the Windsor Castle and soon after Terence Hogan commissioned him to do a video clip for their country-punk song, ‘Bride Of Frankenstein’. It was another job that he put his heart into but it meant a huge amount of work. “Three minutes doesn’t sound very long but with hand-made animation it’s a lot of work, like the equivalent of six TV commercials.”

He remembers working in a loft space next to where Murray Cammick published Rip It Up magazine. He spread huge camera sheets out on the floor so he could see at a glance where the choruses were, where the guitar came in and so on. The result, a relentlessly fast and funny video that pumps up the energy of the song, is a fan favourite around the world.

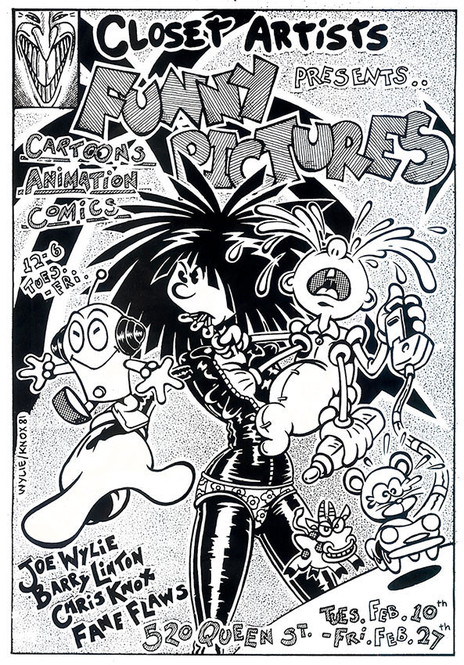

Wylie’s work featured in the Funny Pictures exhibition at Ray Castle’s gallery alongside Chris Knox, Barry Linton and musician and animator Fane Flaws.

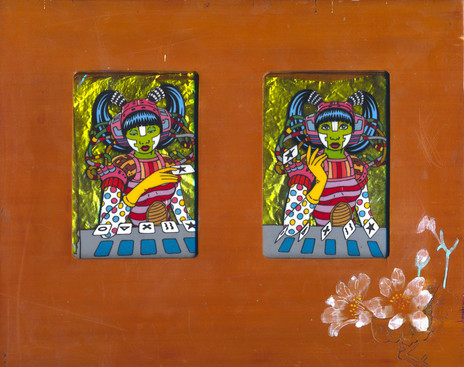

Another joint venture was in Colin Wilson’s black and white comic magazine Strips. Wylie came in on issue No.2 with his Kabuki-style girl hero Maureen Cringe. A later strip – “more jagged and edgy” – was called Decline of the West. The magazine became home to Wylie, Barry Linton, Chris Knox, Laurence Clarke and numerous others. In its short life it is credited with reviving the NZ comics industry. Colin Wilson has since gone on to international stardom.

By the early 90s Wylie was becoming disenchanted with 2D animation as a lifestyle. This was before Toy Story heralded the start of 3D animation and he says it just took too much time out of his life and began to feel like “sadistic drudgery”.

The economic recession saw Magic Films fall over and Joe decided on a complete change. He went back to Christchurch and enrolled as a mature student at Canterbury University, doing several papers in creative writing and gaining a BA with Honours in English Literature.

He didn’t draw for years until the disaster of the Christchurch earthquakes changed his mind. Like most Cantabrians he was hugely affected by the quakes, being made homeless by the first one and becoming politically involved after the second. He found he was going to more demonstrations and rallies than when he was a teenager and it was this that got him back into his own art.

“I just kind of slid into it in the aftermath of the quakes,” he says. “What Christchurch people are so hungry for is some kind of feeling that they’re involved in the reconstruction and at every turn they’re sort of led on and then just cut off at the knees.”

He sometimes appears in online forums but has found making a picture is a better way to deal with it, with the ideas coming when he feels strongly enough about an issue to sit down at his desk. He has contributed cartoons to Danyl McLauchlan’s Dim Post blog site, but his main vehicle is his own site, Porcupine Farm, where he regularly skewers politicians and media personalities.

Why Porcupine Farm? Joe Wylie laughs, “Just being a prick.”

--

Joe Wylie died peacefully on 5 March 2022