Windswept, I blew into town

The Number One I was running down

Didn’t know where I was going

Only knew what I was running from.

(From the song ‘Forty Days in the Wilderness’)

It feels somehow appropriate, given the theme of this story, to be travelling along a long dusty road. I’m on my way to the cabin on a bush-clad peninsula at the top end of the Hokianga harbour, where Johnnie “Timberjack” Donoghue lives. It’s Outlaw Country, a suitable hide-out for someone who has previously been known as a Cockroach, a Bulldog and a Bandido. Johnnie’s been living in the Hokianga for 15 years now, on the spot where the infamous bushranger Jacky “Cannibal Jack” Marmon, himself a Son of the Emerald Isle, lived as a Pākeha-Māori in the first half of the 19th century, including a stint fighting alongside Hongi Hika. Marmon is buried somewhere on this patch, unmarked and upside down to ensure he didn’t rise again.

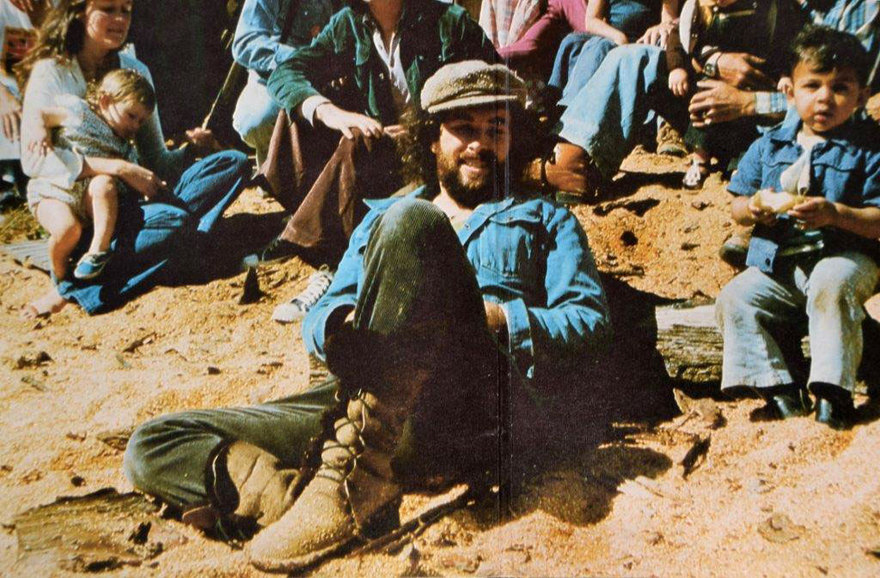

John Donoghue 1975

When Johnnie answers the door, my first question is simple. “What do I call you?” Around these parts he’s usually referred to as JD, sometimes Johnnie but I’ve never really understood the “Timberjack” thing. Johnnie explains it came about when he recorded the single, ‘Dali Mohammed’ immediately after the demise of the band Timberjack. His then producer, Terrence O’Neill-Joyce, pointed out that “John Donoghue” was the Irish equivalent of “John Smith”, so he insisted that they add the “Timberjack” to link Johnnie to his former band. At the time it was quite fashionable – think John “Cougar” Mellencamp – but as Johnnie says, “I hated the name from the get-go. Trust me, if I was to come up with a name for myself the last name that would be is Timberjack.”

But 40 years later, the moniker lingers. “When I finally realised that the name was going to be hammered into my headstone, I knew that I was going to have learn how to live with it.”

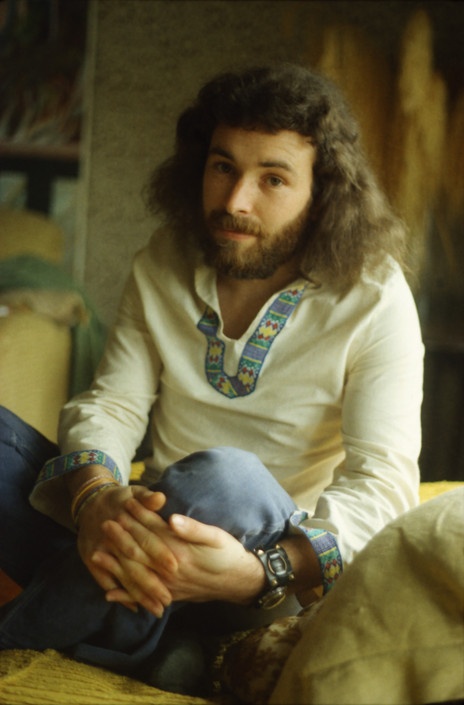

John Donoghue, 1974 - John Donoghue

Johnnie is still working at his music as hard as ever. You may think it’s strange for a working musician to be living so far off the beaten path, but it’s amazing the number of prominent New Zealand musicians who have migrated to the Far North. I’ve known Johnnie since the early 1970s when he was still, as he describes it, in his “overground” period. This was his time spent with The Cheshire Katt, The Dizzy Limits, Timberjack and the Bulldogs Allstar Goodtime Band. I met him when he was playing guitar in Auckland hard-rock band Human Instinct, in those halcyon years when local bands could enjoy six-day paid residencies in packed-out clubs like Granny’s, Grandpa’s or in this case Frank’s, perhaps the only place in town where you could enjoy both blazing hard-rock sets and cool Frank Sinatra standards in the breaks.

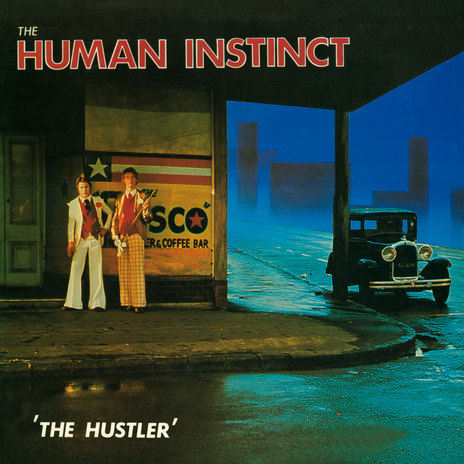

I shot the cover photos for the band’s 1974 album The Hustler and for Johnnie’s solo album Donoghue, the one he was still finishing the night before we both flew out to London in April, 1975. I was going to work on Lost in the Garden of the World, a film about the Cannes Film Festival, trying to convince the New Zealand Government that with a little financial support, our films could have a place on the world stage. For him it was the next logical step after his fourth appearance at the New Zealand Music Awards, including a Loxene Golden Disc nomination for the single ‘Dali Mohammed’, and a New Zealand Album of the Year for Spirit of Pelorus Jack. Back then, pre-internet and Spotify, there was only so far you could swim in the safety of the Kiwi music pond before you had to strike out for deeper waters.

The Hustler album photo shoot with John Donoghue, Glenn Mikkelson (Zaine Griff) and Martin Hope

The 1974 Human Instinct album The Huster featured Maurice Greer, Martin Hope, John Donoghue and Glenn Mikkelson (aka Zaine Griff). Photograph by Susy Pointon

But even as he was working on his second solo album at Stebbing studios in Herne Bay, Auckland, Johnnie was already questioning the road map for his creative journey. The original plan was to take his LP to London and use it as a calling card to advance his solo recording career but by then he had worked alongside and observed at close range enough major overseas touring artists to know that he didn’t want what they had. And what was that? I ask him. “All of it,” he says. “The total lack of privacy, lack of control, the claustrophobia and pressure from the commercial imperatives of the mainstream music industry.” Fair enough, but if fame was a one-way street you didn’t want to go any further down, but you still loved writing and playing music, what was the alternative?

Fork in the road

Warm Pacific sun is calling, drawing me from this land,

A land so cold it chills the soul, destroys the love of man

I was born to feel the sea and watch the seagulls fly,

Not to fight for every breath and watch a nation die.

( From ‘The Departure’ by John Donoghue and Shona Laing)

The answer to that question lay not in the rock spectacles of Wembley Stadium but in the streets and underground of a nation that was experiencing considerable social turmoil by the time we arrived. We got off the plane at Heathrow to the clamour of political pundits claiming that England was no longer governable, race riots in Ladbroke Grove, IRA bombs on Oxford Street and graffiti on crumbling tenement walls that offered a simple solution: Feed The Poor: Eat the Rich. Our neighbourhood in a pre-gentrified Notting Hill was a political hotbed and home to a vibrant passing parade of dreadlocked Jamaicans, bohemians, Portobello buskers, gypsies, vagabonds and thieves.

Music was everywhere and we soaked it all up, including the landmark Bob Marley concert at the Lyceum that threatened to start a revolution; Maria Muldaur performing ‘Midnight At The Oasis’ at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club backed by Elvis Presley’s drummer Ronnie Tutt and Little Feat’s Bill Payne on keyboards; Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon staged, complete with a formation of Spitfires and a replica rocket ship, in front of a 100,000 strong crowd at Knebworth; and smoky nights at The Half Moon in Putney where a few pints were all you needed to enjoy sets by guitar virtuosos Bert Jansch and Richard Thompson.

In pre-punk London, music was at the forefront of protest and social change.

The tide was turning. In these pre-punk days in Ladbroke Grove, music was at the forefront of protest and social change. After a decade of rock stars affecting the lifestyles of the aristocracy, skinheads and bovver boys found expression in reggae and ska, imported by post-colonial immigrants from the Caribbean, to voice their discontent.

But the biggest musical influence on Johnnie during that period was the London underground troubadours, whose acoustic music could be heard echoing through the approaches to the Kings Cross Station, Charing Cross, Edgeware, Finsbury Park and Paddington. He realised that what was going on down there was much more than amateurs just busking for small change. The acoustics of the tunnels and the passing crowds gave these professional musicians the opportunity to perform rigorous R&D on their new compositions, before introducing them to the critical audiences of London’s popular folk clubs. By the time they delivered the same songs to their electric bands, they had been honed and refined to a high polish. Even better, this entire process happened without the intervention of the commercial music industry. As Johnnie recalled, “When I figured out what they were doing, that’s when I said, that’s me and that’s where I want to be, for the rest of my days.”

But not in the congested teeming metropolis of a nation reeling from post-colonial payback. Johnnie knew that the stories he wanted to tell were set, as the poet Denis Glover proposed in his 1936 poem Home Thoughts, not in Sussex Downs but “in Johnsonville or Geraldine”.

There’s a grave overgrowing up Holly’s Hill

On Kau Kau overlooking Johnsonville

With the words on the headstone a mystery

When the hills turn to gold

No more wars there will be.

(No More Wars)

The road less travelled

When Johnnie returned to New Zealand in 1975 it was with a new sense of purpose and resolve. In an interview with Radio Windy DJ Peter McIlwaine soon after his return, Johnnie lamented the Kiwi cultural cringe that viewed anything local as inferior to the imported product. While McIlwaine sympathised with Johnnie’s desire to write songs about Johnsonville and Geraldine, he was sceptical: “Yeah ... for instance, no one's ever going to write a song called ‘Rainy Night in Ngauranga!’”

Rainy night in Ngauranga

Thought I’d go north for a while

But it’s cold, cold, cold

Outside the freezing works

Getting kind of hard to raise a smile

(Rainy Night in Ngauranga)

Undeterred, Johnnie bought a van, filled it with essentials and headed on a pilgrimage north, which eventually led him to the end of State Highway 1 at North Cape, Te Rerenga Wairua and the rural settlement of Te Hapua. He stayed with Paul and Denise Norman at the Ngāti Kuri settlement of Te Aporo, living the life of a hunter gatherer, the perfect antidote to the cultural confusion of urban London.

It was at this time that Ngāti Kuri found themselves in a legal battle to fight a corporate grab on sacred land, a waihi tapu. To raise the legal fees, they put out a call for local musicians who would be prepared to play, unpaid, for a fundraiser. Six musicians showed up to help out, Johnnie among them and Cockroach was formed. (The name came from the need to put the yet-to-be-formed band name on the poster advertising the event. While the committee were deliberating, a cockroach crawled across the table). The event was a success and the impromptu band enjoyed such an enthusiastic response, they went on to become one of New Zealand's first successful indigenous rock bands. Over the next three years they played their eclectic mix of original locally themed songs and raucous covers in gigs throughout the north and beyond, with notable performances on the main stage at the 1979 and 1981 Nambassa Music Festival. After several metamorphoses, the band, now named Rockcoach, downsized to comprise Richard Rua Mason, Derek Barnston and Brent Andrews, the line-up that would evolve into the Electric Puha Band.

Up here where the time moves slow

Soft winds through the nikau blows

Heart and mind in harmony

Rangaunu moon rise from the sea

(Moonrise Rangaunu Bay)

Johnnie’s songs had always reflected his environmental concerns – think 1972’s ‘Spirit of Pelorus Jack’ – but by now, as he recalls, the Far North had worked its magic on him and, “my world view had somehow changed – I found that I was looking at the world through not wholly Pākehā eyes. I realised what was important was the unification between Māori and Pākehā and our mutual responsibility to protect Papatūānuku. Living in a Māori community only reinforced my growing awareness of the Earth as a conscious being. This is a concept that is understood and honoured in Māori culture but even more urgent now to acknowledge with climate change and the exploitation of the environment.”

An unexpected detour

Here I stand, at the edge of my life,

Looking back at those times,

I turned left, when I should have turned right..

(from the song ‘Bluelove Waterfall’)

In 1980 Johnnie’s plans were disrupted once again when he received a disturbing letter from his mother. He realised he needed to move to Wellington, to support his aging parents. When he got there he started looking for ways to support himself. Eventually he joined The Mangaweka Viaduct Blues Band, a vehicle that allowed him to work on blues and his slide guitar technique. The band enjoyed success from 1980 to 1984, locally, regionally and with appearances at the iconic Gluepot in Auckland. Then Johnnie moved on to co-form one of New Zealand’s most acclaimed acoustic neo-country bands, The Warratahs, with fellow singer-songwriters Wayne Mason and Barry Saunders. Their inspiration for a true revisionist country band, playing original locally themed material came from a mutual love of Hank Williams. He recalls that Chet Filippo’s biography, Your Cheating Heart, was passed reverently among the band members.

The short-lived Warratahs line-up between The Only Game In Town and Too Hot To Sleep, 1987. Left to right: Nik Brown, Rob Clarkson, Barry Saunders (front), Wayne Mason, John Donoghue. - Photo By David Hamilton - Murray Cammick Collection

They were joined for their standing-room only gigs at Wellington’s Cricketer’s Arms by drummer Marty Jorgensen and violinist Nik Brown, and their first album The Only Game in Town was soon enjoying high rotation on Wellington student radio. By 1987 The Only Game in Town had gone gold, taking out New Zealand Country Album of the Year while the band took out the Top Group Award at the Gore Gold Guitar Awards.

But Johnnie’s tenure with The Warratahs was always going to be short lived, he explains, because of his commitment to developing a recording studio that would allow independent artists like himself “access to the means of production” without industry control. “I left in July 1988 to become a company director at Wellington's Pacific Sound Recording Studios.” The following year, he put together the line-up for his own rock and roll band, Johnny and the Skyhawks. This was to be Johnnie’s first and final attempt at being a bandleader. I asked him how it went. “Never again…!” he says with a shudder.

So I head out on the highway, to run my lonely mile,

I came to the mountain, and I climbed real high

And I followed the river, to where the big old trees grew tall,

And I found there's no water at the bluelove waterfall

(From Bluelove Waterfall)

It was only after his parents both passed away that Johnnie felt he could return to his spiritual homeland in the north. In September 1994 he reunited with his old bandmate Richard Rua Mason in Whangarei and jumped on board a powerful vehicle with Mason’s Electric Puha Band. With its mix of home-grown originals and hard core thrash-metal rock, Electric Puha had become a favourite of the Northland gangs. Over the next few years, they performed regularly for enthusiastic audiences of Black Power, Mongrel Mob, Hells Angels, Roadrunners and the Tribesmen, culminating in a landmark concert performance at Paremoremo maximum security prison. When I ask him about other highlights, he cites the fact that Electric Puha’s one and only single, ‘Sweet Music In Te Hapua’, became an Aotearoa Radio favourite and holds the dubious title of being a No.1 hit on the station long before the funds were finally raised for it to be actually released in 1990.

The Electric Puha Band played its last gig at the Kohukohu Hotel, on the Hokianga Harbour, on New Year’s Eve, 2001, victims of the rapidly diminishing Great Northland Pub Circuit. Johnnie and his former bandmates were still in constant work, however, with their alternative acoustic band the Puha Bandidos. With the street band, Johnnie had long harboured a desire to return to his skiffle roots and to explore the intriguing question of how bands in the long-distant past were able to entertain large groups of people prior to the advent of electricity.

John Donoghue (right) in The Bandidos, 2001. He regards this band as his most satisfying artistic achievement.

The original acoustic band had a modest start, going back to 1993 with Johnnie and Richard performing as a two-piece at the Whangarei Big Fresh supermarket. As he recalls, “The gig required us to sit up in the ceiling, where we soon discovered that customers could hear us but not see us. To become visible we took to wearing two giant Mexican sombreros. Local restaurateur Reva Merrideth heard us performing at the supermarket and booked us to play in her restaurant. When she saw us turning up to play in our sombreros, Reva declared we looked like ‘a couple of Bandidos...!’”

The open highway

Standing on the corner for my pay

I sing my songs

I strum and play

But the blues they just won’t go away

Just another day out in the life of a working man

(from ‘The Working Man’)

Once again the timing was spot on. The North was ready for a 100 percent acoustic street band. Johnnie remembers, “In the early 1990s, Whangarei had just built the Cameron Street Mall – the city had a progressive mayor and a supportive retailers association who got right behind our street music. They recognised its ability to draw crowds and revitalise what had been a tired CBD.”

Guiseppe De Plonk multi-tasked with fire-eating, sword-swallowing, knife-throwing, juggling and washboard.

Increasing demand for their services allowed Johnnie and Richard to bring in other members of the Electric Puha Band, who were then armed with various skiffle-type instruments. Eventually the line-up boasted guitar, tea-chest bass, dobro, mandolin and the highly improbable Guiseppe DePlonk, multi-tasking with fire-eating, sword-swallowing, knife-throwing, juggling and washboard. Although his tenure was relatively short-lived due to the inevitable collateral damage, the band continued with players coming and going as required. Their popularity led to appearances as far south as Christchurch and as far north as Rarotonga, where they mounted a highly successful two-week tour in 2004.

The unique wholly acoustic line-up and high entertainment value of the Puha Bandidos ensured they had a wide appeal and could perform at a diverse range of gigs, from pubs to street fairs and markets, A&P shows, arts festivals, television shows, weddings and TV appearances. They also became a fixture at the burgeoning annual Waitangi Day celebrations held at the Treaty Grounds from 1996.

Johnnie rates the 15-year reign of this wholly acoustic band as his most satisfying artistic achievement. “It was the dream I had harboured since those days in London. That’s what I came home to do – exactly what those London troubadours did – to be able to work out originals, alongside our rock repertoire, out in the streets. We were playing AC/DC and Led Zeppelin classics with pots and pans, alongside lots of originals, Kiwi covers, adapting the set list to our audience and the situation with no specific genre. I had had street bands before this in Wellington (The Warratahs won first prize in the Busking Competition at the 1987 Gold Guitar Awards) – in fact, all through my career the street thing was threaded through everything I did but it was not till the 15 years of the Bandidos that I was able to give it full expression.”

The road goes on

We are like candles, that burn so bright,

And these days of our lives, just candles in the window,

Blowing in the wind.

(From the song "Candles")

The reign of the Puha Bandidos came to an end with the untimely passing of Richard Rua Mason in 2006, but with his current projects Johnnie continues to honour his legacy.

“He and I had been musical partners and friends for so many years that losing him put me in a tailspin for a long while. Richard was a great believer in Māori and Pākehā working together and combining the best parts of each culture into an exciting new whole. He also proved by example that we could do it without surrendering our existing social identity.”

The Northland Titanics, 2018. From left: Alex Simeti, Billy Kristian, John Donoghue, Dave Gorrie. - John Donoghue

Johnnie’s story epitomises all the twists and turns, the ups and downs, the highs and lows of sustaining a lifetime career as a New Zealand working musician. He is one of the last of those who emerged during the late 1960s who is still working regularly and has not had to resort to another career to pay the bills. Throughout all the changing fortunes of the music business and the shifts and turns in our culture, Johnnie has continued to write and perform at a rate that many younger musicians can only envy.

Among his current projects are The John Waynes – a duo formed with old Warratahs bandmate Wayne Mason, that has continued off and on since 1984, as well as annual solo appearances at the Treaty grounds on Waitangi Day and his latest project, The Titanics, a Northland “super group” made up of Johnnie and Dave Gorrie on guitar and vocals, Billy Kristian on bass, and drummer Alex Simeti. And after a successful gig at the 2018 Mangonui Festival Johnnie is as upbeat as ever, with a stack of new original music all ready to record. As he puts it, “I feel with the Titanics like I might be on one of those sleigh rides, when all the planets line up and a band takes off, unless of course it hits some stupid iceberg.”

--

John Donoghue died on 9 February 2024.