Mark Williams should really have been born hollering: “Here I come, ready or not.” Because, by the age of 20, his afro, satin flares and eyeliner was pushing groove and ambiguous glamour onto a musical landscape dominated by earnest hippies, cookie-cutter family entertainers and pub rockers. Ask anyone who was a child when they first saw him on television – he was impossible to miss, given New Zealand only had one channel – and they’ll likely recall the instant reaction of the adults in the room: “I can’t tell if it’s a boy or a girl…”

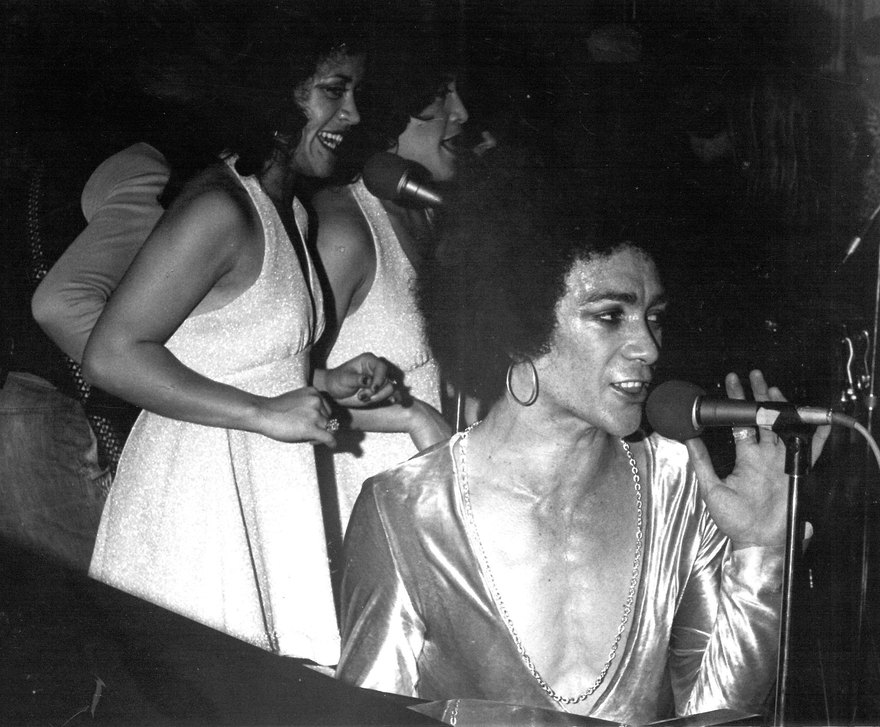

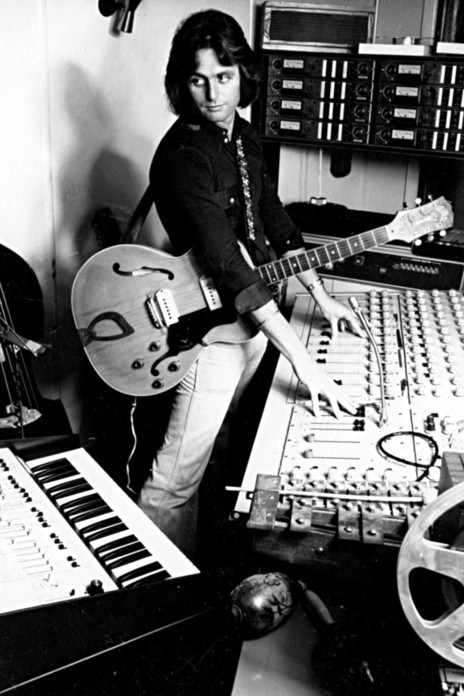

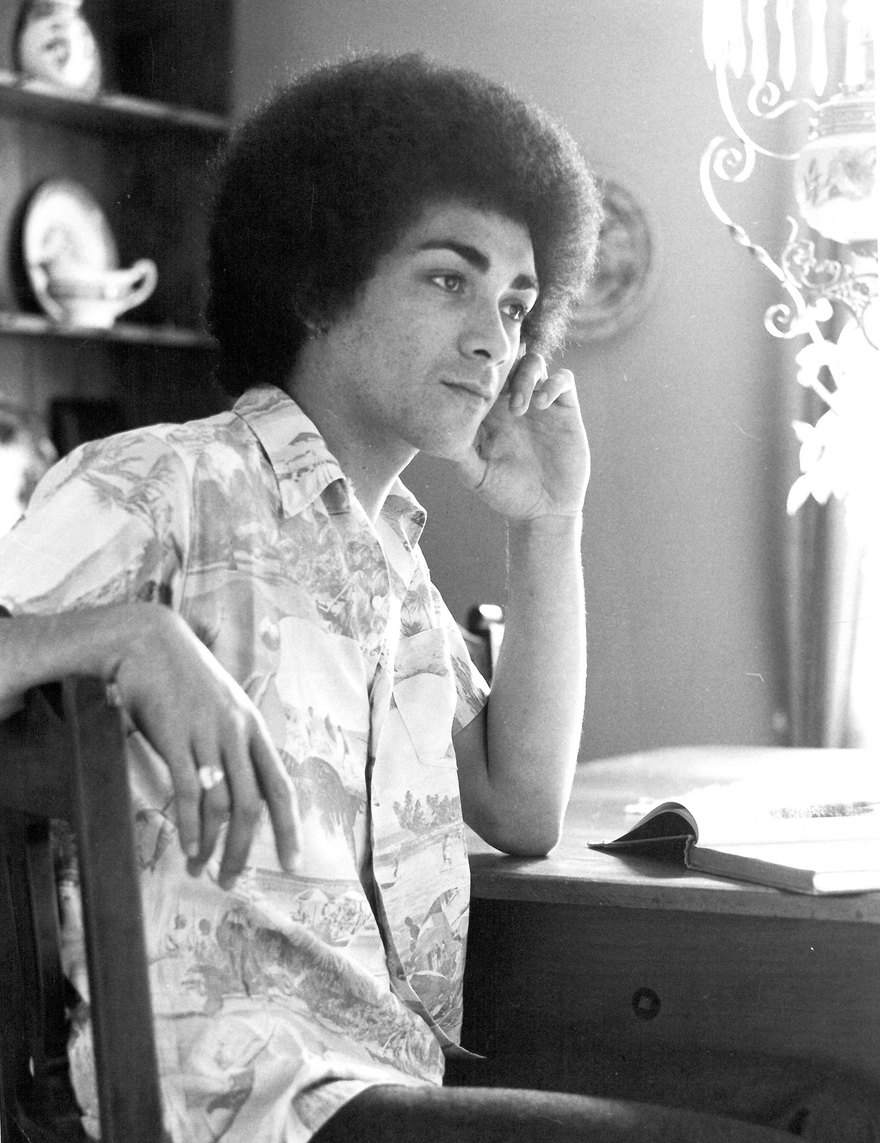

Mark Williams, circa 1975. - Phil Warren Collection

And in mid-70s New Zealand – a country besotted with the regressive bullying of Prime Minister Robert Muldoon – that was not a comfortable niche to claim. Even within his own family. Yet they can share credit for launching his career. Both parents had been performers around Northland in their younger days, and his mother kicked off his piano lessons when he was only four.

But Williams’s drive to follow his own path began in his hometown, Te Kopuru, 14 km south of the Northland town of Dargaville. In the late 60s he heard the sound of guitars coming from a neighbour’s home. The Tanes had bought their two boys amplifiers and Williams immediately wanted a go. Mack Tane, the older of the brothers, went a step further and began teaching his schoolmate how to play.

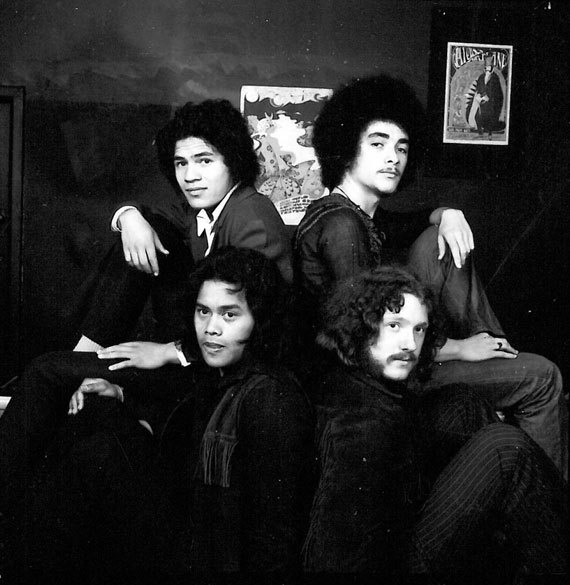

That was it: music was now to be Williams’s life. At the end of his sixth form year he and his friends left Dargaville High School to form a band, Face. They were joined by Willie Hona, who was known locally for his guitar skills (he would later be a member of Herbs). While Hona lived further north in Rawene, he would stay with the Williams family when the band gathered to practise.

Face, 1972 with Mack Tane (top left), Willie Hona (bottom left), Mark Williams (top right) and Gregg Findlay (bottom right). - Phil Warren Collection

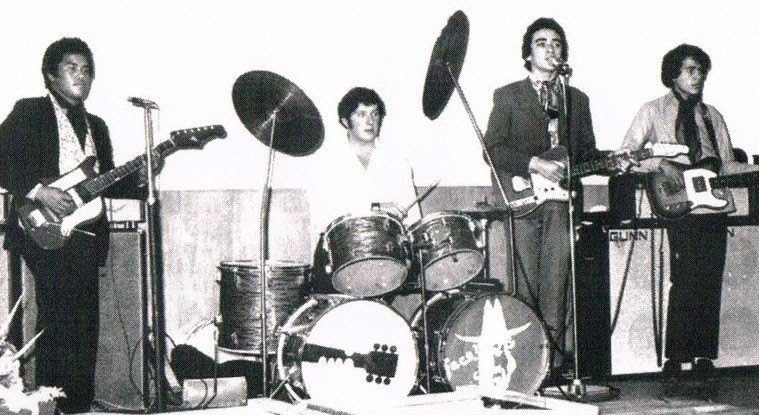

Face began travelling most weekends using a van bought by the Tane family. Their usual set ranged from New Zealand guitarist Peter Posa to the Shadows and on through to Black Sabbath and Hendrix.

In 1971 they were making weekly trips to Auckland to perform for the local Samoan community at the Otahuhu Community Centre. Each gig earned them $20.

Face also entered that year’s Whangarei heat of the Battle of the Bands competition, and won: “We were up against bands of a ‘certain’ calibre,” says Williams, “we were just raw energy and that got us through.”

Face in action. Left to right: Mack Tane, Mark Williams, Gregg Findlay, Willie Hona. - Simon Grigg collection

They came third in the national final, behind Aucklanders Tramline and The Lord from Christchurch, and did enough to impress promoter Lew Pryme, who convinced them to move to Auckland full time. But gigs were few and the boys, still teenagers, found themselves in the big city and stoney broke.

Williams has admitted his situation got so bad he resorted to stealing milk money. The only concession he made to earning outside of music was a short-term car washing job that paid for a new amp.

Face, left to right: Willie Hona, Gregg Findlay, Mark Williams, Mack Tane. - Gregg Findlay collection

The band’s prospects remained dire until their Otahuhu connection secured a year-long bar residency, an opportunity that earned them further gigs outside Auckland (even if they were still too young to drink).

Their sound became sought after and they found themselves backing acts as diverse as Bridgette Allen, Australian pop singer Normie Rowe, Bunny Walters and Steve Allen. And they still couldn’t read a note of music.

In 1973, Pryme got them a gig at the Kensington Carpet Awards, a television industry event, where they debuted their new glam look with glitter, make-up, platform shoes and tight, satin costumes. Williams made the costumes himself on his girlfriend’s sewing machine. If the image outraged some, the resulting attention saw NZBC (New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation) producer Kevan Moore invite them onto Free Ride, the network’s replacement for the long-running Happen Inn music show.

But the Face soon fell apart when, after a gig in Whakatane, Williams took the band’s $100 fee and spent it on a night out. The resulting squabble killed the band and Williams moved out of their Herne Bay band house and in with his girlfriend, Pam. They are still together.

Face only recorded one single, ‘Hangin’ Around’ b/w ‘Mr Postman’ (the B-side was a Mark Williams composition), which was released on Zodiac in 1972. The production is credited to Dave Russell and Ray Columbus of Invaders fame.

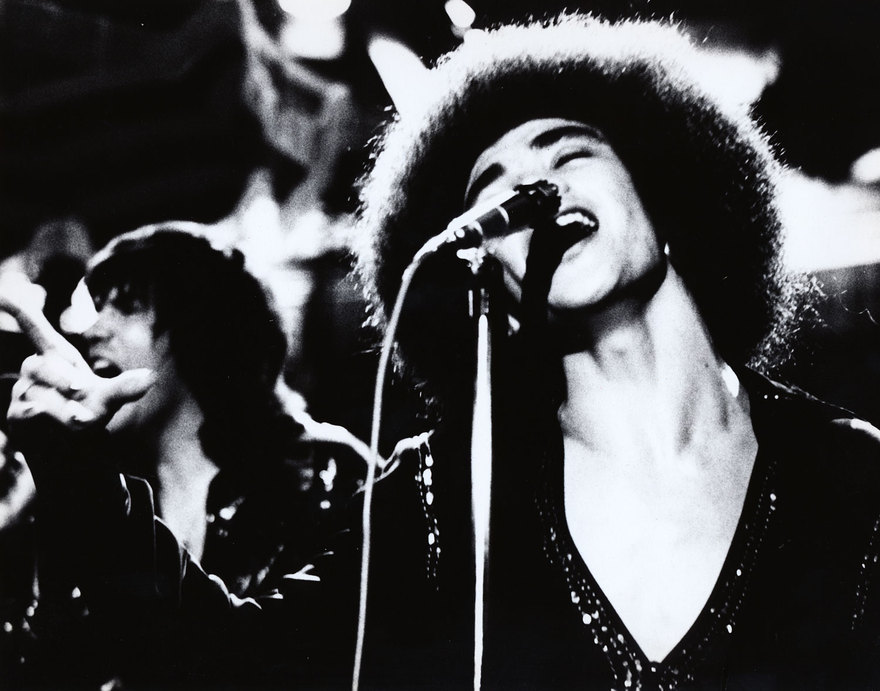

Free Ride then changed everything and launched Williams’s solo career. His trademark look – slinky, bedazzled and sexually ambiguous – caused an immediate storm and he was cranking out two new outfits a week to keep his look fresh. It was a look New Zealand had never seen on prime time television, especially coming from a young Māori.

A target was now on his back.

“It was horrible, absolutely,” he says. “The cat calls and that sort of stuff, it was weird. I was pushing the limit I guess, but it was very small minded. I was just being me.”

Even his father turned against him. But Williams refused to be intimidated or swayed. In an interview with Radio New Zealand he remembered: “I had my own instincts to go by, I don’t know why I did it, but I was taken by people like David Bowie and all of that whole glam era, and I decided to follow that route because it felt quite natural … Bless New Zealand, I was derided on the one hand and loved on the other – I couldn’t walk down the street without one thing or the other happening.”

Mark Williams. - Murray Cammick Collection

It’s hard to imagine how he survived the baying and threats from pissed-up, provincial punters once he hit the pub circuit. He didn’t have a regular band to watch his back either. As a solo artist, he’d arrive in town, meet the local backing musicians and teach them his set from scratch. And he would do that week after week. He also wasn’t playing the expected rock covers and instead presented a set of soul and funk.

Then a collaborator emerged. Wellington producer Alan Galbraith had recently returned from England to assemble a stable of recording artists and contacted Pryme to ask if Williams was interested in releasing an album. Why yes, he was – and so, in 1974, Williams signed on with EMI. He arrived for his first session and promptly lost his voice (a persistent problem not helped by his heavy smoking).

Alan Galbraith, 1974, in an EMI publicity shot. - Alan Galbraith collection

“I was always working alone and I suffered from anxiety. It was stress, I was getting shit all the time and I still wasn’t a mature artist.”

In an interview with the Taranaki Daily News, Williams remembers how intimidating the EMI recording studio appeared: “It looked like a control room from Flash Gordon.”

It didn’t help that his backing group was frontline Wellington outfit, Redeye, which was made up of former Quincy Conserve and Dizzy Limits members.

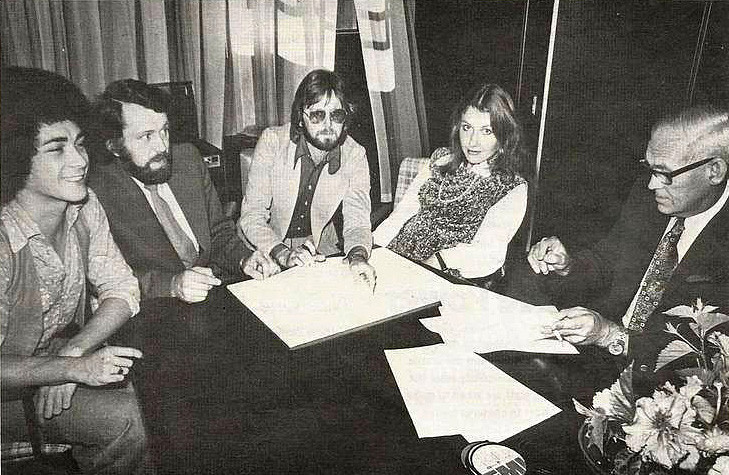

Alan Galbraith signing his producer contracts with Annie Whittle and Mark Williams at EMI 1975.

But his excitement dimmed when Galbraith played him ‘Yesterday Was Just The Beginning of My Life’, a song written by Australian songwriting duo Harry Vanda and George Young. Williams hated it, but Galbraith held fast until the singer reluctantly agreed to try rearranging it with a Māori groove.

It worked and excited by the result, Williams rushed off to play it at his next gig at the Sandown in Gisborne. The crowd hated it.

Undeterred, the sessions continued with Galbraith increasingly applying the British funk sound used by the likes of Hot Chocolate. ‘Disco Queen’ was one such number even though Williams had been hesitant about recording a strictly disco track. As a soul/funk guy he didn't see disco as his genre: “So in a sense that was Alan who decided it should go on the album, a song for the DJs.”

‘Celebration’ was chosen as the first single which did okay but did nothing to prepare Williams for the reaction to his second single, ‘Yesterday Was Just The Beginning of My Life’.

“Everything became a blur.”

With the song storming the charts, a “meet the fans” event was held at Western Springs, Auckland, with about 4000 screaming kids showing up to witness Williams arrive in a hot air balloon.

Again, he had laryngitis and after battling to the stage he was struggling through his song when a moth flew down his throat: “I managed to spit it out, but it ruined me for the gig.”

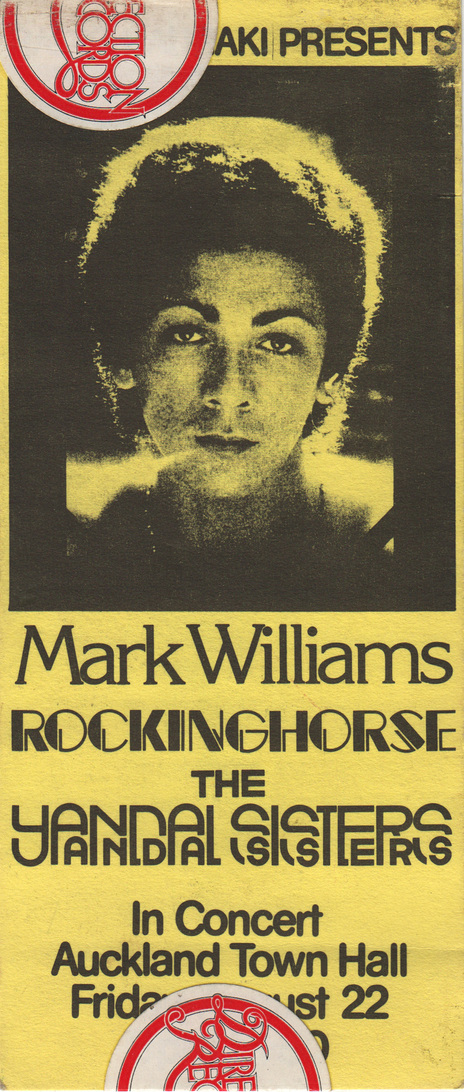

Mark Williams, August, 1975, at Auckland Town Hall with Rockinghorse and The Yandall Sisters - an all EMI line-up.

With the song done he again forced his way through the crowd – they tore his clothes and ripped his hair – to reach the balloon. It rose to about 50m when the wind changed and forced it back down again “and back into the madness, I had to fight my way out all over again.”

The next day he was diagnosed with polyps on his vocal chords and for the next three months, with ‘Yesterday …’ at the top of charts, Williams couldn't sing a note.

His self-titled debut album peaked at No.2 and remained in the charts for 30 weeks, making it the highest selling New Zealand album of the year.

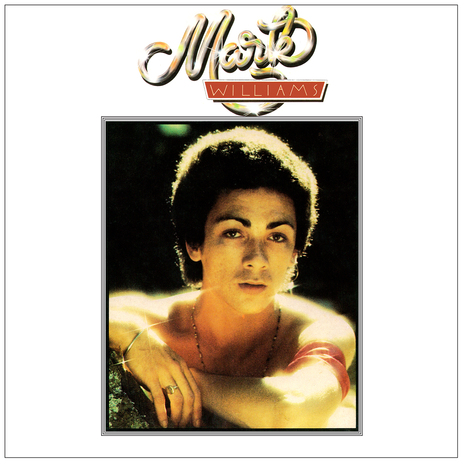

The cover of Mark’s 1975 debut, designed by Kevin Dunkley with photography by Michael Baigent. The first of a very successful three album collaboration with producer Alan Galbraith.

He was away and in 1975 found himself touring with another strutting peacock, Gary Glitter. But his popularity hadn’t lessened the impact of his look with at least one school principal asking him to tone it down for his students. Later that year, Williams was awarded the inaugural Gold Microphone Award, for most professional performance of the year, at the New Zealand Variety Artists convention.

His biggest problem was now dealing with demand. “Mark’s big failing,” his life-long partner, dancer Pam Beadle, told the Listener in 1977, “is saying yes to everything. I hear him on the phone saying ‘Yes, all right, I’ll do that’ and I have to grab it and yell ‘no he won’t.’”

In reply, Williams said: “When ‘Yesterday …’ hit the top I thought, like so many other people, that I was just a one-hit wonder. I was reluctant to accept the first success, but after I recovered I began thinking that if I've really got it inside, I should get out and see what I can do with it.’

A grouping of EMI artists circa 1976. Mark Williams, The Yandall Sisters and Rockinghorse with EMI's Rick White (second from right, rear) and Alan Martensen (kneeling, right). - Rick White collection

So he had serious ambitions for his second album, Sweet Trials (1976). If the production team remained the same, his backing now came from Rockinghorse, a quasi-supergroup of Wellington musicians Galbraith was hoping to craft into a studio act, much like LA’s Wrecking Crew.

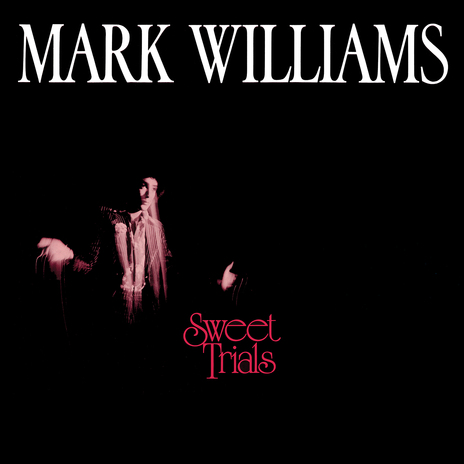

Steve Henderson’s design for Mark Williams’s second album, Sweet Trials, released in 1976, with photography by Alan Guildford.

But the tide was against them this time. Not only was Williams having more throat problems, the New Zealand government had increased the sales tax on recorded music. As a result, sales slumped and labels became jittery about releasing anything that wasn’t a guaranteed hit. Local music suffered.

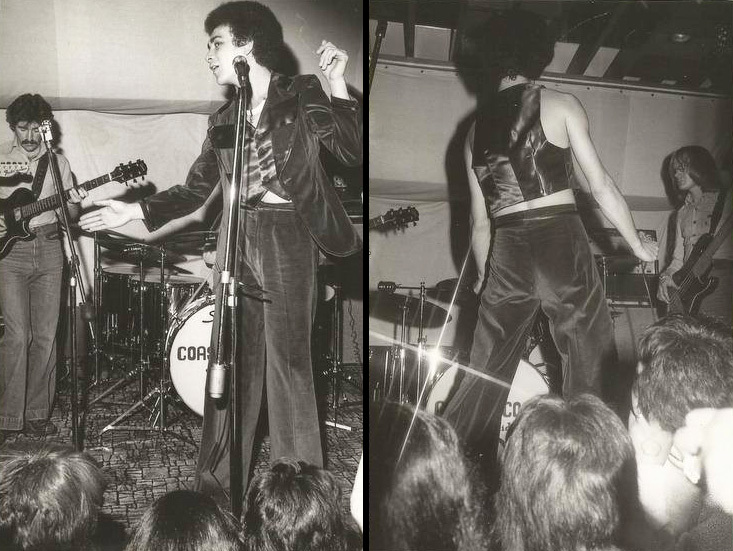

Mark Williams on stage in 1976 with the Coast to Coast Band: Rick White, Bruce Robinson, Gavin Peacock, Alister McQillan, Paul Boyes and Daryl Kidd - Rick White collection

When the album struggled to No.14 on the music charts – with the singles, ‘Sweet Wine’ and ‘If It Rains’ peaking at No.7 and No.25 respectively – Williams’s career dipped. He took some of blame himself, believing that his efforts on Sweet Trials were “probably too introverted to be successful.”

Everything now hinged on the last album required by his EMI contract and another operation on his vocal chords.

But 1976 first saw him taking an unexpected tangent to communist Poland for the 16th International Song Festival. Again, his satin slacks and makeup divided people: “A lot of people took to it, but a lot of people didn’t and they weren’t shy about telling me.” Still, he played the festival, did a few solo gigs and even appeared on Polish television. He earned a lot of money, all of which was confiscated at the airport.

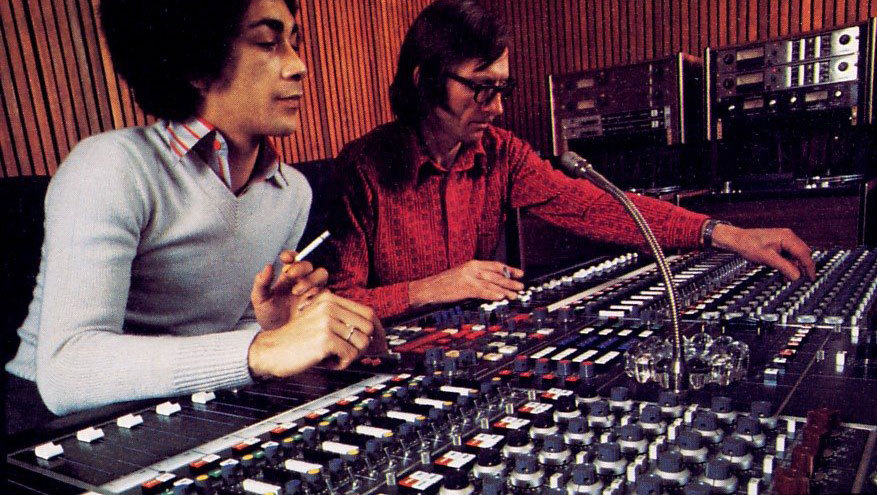

Mark Williams with engineer Peter Hitchcock in the EMI Studio, Lower Hutt, Wellington 1976.

Back home, he found Galbraith had another single in mind, Buddy Holly’s ‘It Doesn’t Matter Anymore’, and again, says Williams, “my reaction was that I didn’t want to do it.” Nonetheless he met with arranger Dave Fraser. After disagreeing on what approach to take, three versions were recorded with a shifting cast of musicians, with the first proving the keeper.

The final album, Taking It All In Stride, was released in June 1977. It didn’t do much better then Sweet Trials, but still spawned three singles, the title track (which also reached No.14), ‘House for Sale’ (No.13), and the massive ‘It Doesn’t Matter Anymore’ which became Williams’s second No.1 hit and the biggest-selling single of the year.

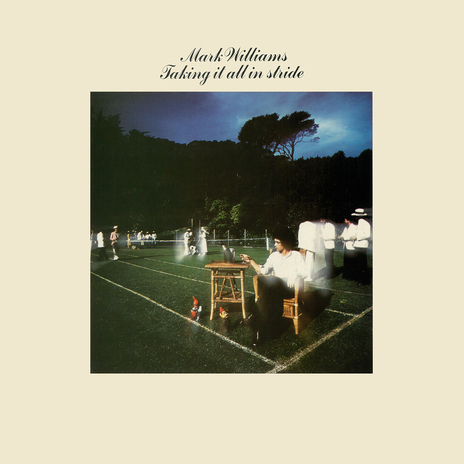

Daryl Watt’s Hipgnosis-like cover for Williams' 1977 LP, his final for EMI before heading to Australia with album producer Alan Galbraith, who had by this time become his manager.

His rendition of Millie Jackson’s ‘A House For Sale’ is now prized by modern and Northern Soul collectors.

The album then received the highest number of nominations in the 1977 New Zealand music awards, winning a brace of technical prizes, and best male vocal performance for Williams, although the album itself lost out to Douglas Lilburn’s Symphony Number 2.

Williams was then pipped for the Entertainer of the Year title by childrens’ television presenter, Chic Littlewood.

So, in July 1977, with his EMI contract having expired and no one seeming in any rush to renew it, Williams sat down to discuss his future and the perils of success with Rip It Up magazine.

Mark Williams. - Murray Cammick Collection

“The good thing about what we’re doing now is that nobody’s trying to mould me … I think EMI did in a lot of ways, in their expectations.”

He was also critical of the breweries, who saw musicians more as a means to sell more beer than as promotable attractions in their own right.

But, more than that, he felt he needed to disappear for a while: “One of the biggest mistakes in a country this size is to keep pouring things out as fast as you can. After all, you can only do it for so long and people get bored with you. It’s happened to every entertainer in New Zealand, after so long you just become totally over-exposed.

“I got kickback on that too. If I’d go to a club there’d always be one or two who’d really despise what I was doing.”

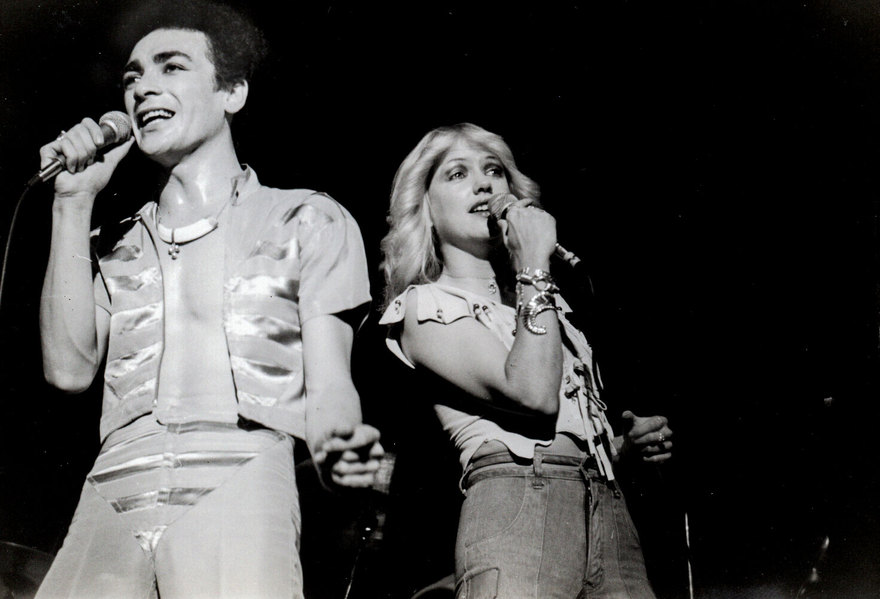

Mark Williams and Sharon O'Neill in the late 1970s - Photo by Murray Cammick

Now managed by Alan Galbraith (who also looked after Sharon O’Neill and was off-contract with EMI), he announced one final tour before heading offshore.

Galbraith put it this way: “It’s quite nice living here, but there’s just not enough to do.”

“I know I’ve got to get out of here now,” added Williams. “I didn’t want to and I’ve always maintained I didn’t want to, but …”

--

Mark Williams – the Australia Years

Auckland music writer Alan Perrott co-compiled the New Zealand funk compilation Heed the Call, which features Mark Williams's versions of ‘A House For Sale’ and ‘Disco Queen’.