In 2019 for an AudioCulture column on “deep cuts”, Auckland singer-songwriter Greg Fleming singled out ‘Ghost Town’ as an “acoustic slice of small town noir” in which Clancy “creates a compelling intimacy with lyrics that seem almost tossed off and yet are all the more powerful for it”.

He also mentioned the subtle production by Andre Upston, and Clancy’s skill and courage as an artist who put her heart and soul on the line.

“The fighter in me and my overwhelming love for music and singing took over.”

Although she has usually been private about some aspects of her life, in recent times she wrote on her Department of Hearts page of being sexually abused as a child and “when I realised no one would help me, I turned to the dark side and deep into the substances I dove – in a spiraling deathwish – my life forever changed”.

“But the fighter in me and my overwhelming love for music and singing took over, steering me headlong into the cathartic power of a song, of an immersion in sound, where the feeling of Wrongs Being Righted reigned, if only for a minute, in the place of transcendence, of elevation, in the presence of something greater than me.”

These days Miriam Clancy, her husband and four children live in Kutztown, Pennsylvania where they have bought a home (“way cheaper than anything you’d get in New Zealand”) and she has played selected gigs in nearby New York.

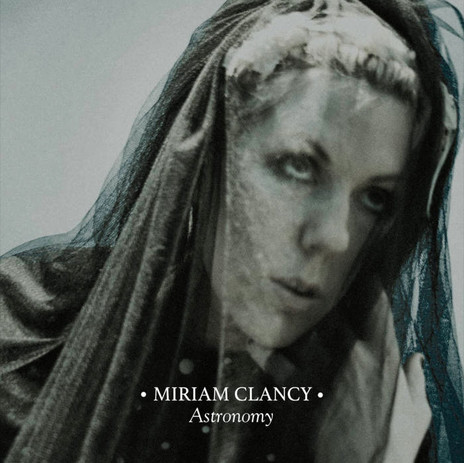

The five years since their move to the US had been tough, she admitted to me in a 2019 interview in advance of her new and very different album Astronomy, which erred to rock and electronica. She’d come a long way – emotionally, physically and creatively – from the Foxton of her childhood which prompted the compelling ‘Ghost Town’.

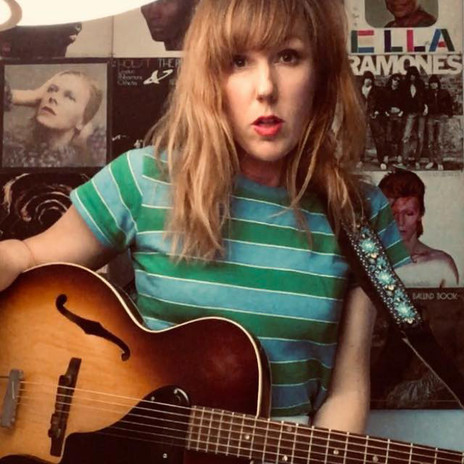

Clancy was born to a Croatian mother and Irish father who were both musicians (“and a fiery blend of genes”). After they separated when she was three, she lived with her mum who played Little Feat, Neil Young, Janis Joplin, Joan Baez, and Neil Diamond around the house.

Being a child of the 80s however she added melodic Fleetwood Mac, the urgency of early Bruce Springsteen, the wham-glam of David Bowie and Prince to the mix: “Prince really shaped me although you can’t hear any of that in my music, but the guy is a genius.”

Then at 16 she left school, took a “stink job” for a while, then hooked up with musicians on an Access course. She joined their band as lead singer and for the following four years played around the pubs of the Foxton and Levin area. Get her at the right moment and she’d even admit to having played bagpipes for a few years in Foxton.

By 20 she’d seen and done it all, and was looking for something more. She lit out for Wellington and worked with jazz musicians, all the time expanding her musical parameters.

When she heard that Auckland R&B rocker Ted Clarke was looking for a singer to join his outfit for some gigs in Malaysia she grabbed the opportunity. “I packed my bags and came to Auckland – then sat around for months waiting for the trip to happen. We went in the end and I’d always said I was not going to go overseas until music paid for it. And it happened, although maybe a little later than I thought.”

It was on her return to Auckland that she decided to listen to what she now calls “more pensive music” and to stop knocking herself out in clubs and bars with Clarke’s Backdoor Blues Band and the Rockafellas.

She had churned out covers of rock classics by AC/DC, Bon Jovi, Cold Chisel and Pat Benatar, and professed a passion for the music of Detroit’s working-class rocker Bob Seger. But a change was happening in her listening and what she wanted to do. “I’d liked early Sheryl Crow and that might have spurred me on into thinking that I could do that kind of thing.”

And so – entranced by the songs of Elliott Smith, cult figure Ray LaMontagne and Gillian Welch – she started to explore a deeper and more emotionally intelligent musical palette which came to fruition on her debut album Lucky One in 2006.

She road-tested the songs and herself in a series of low-key gigs around Auckland, notably at that now former mecca for singer-songwriters, the Temple on Queen St where she played almost every week for a year.

Lucky One – which she co-produced with Steve Roberts at York Street Recording Studios – was a strong and consistent collection of original songs which invited comparisons with American alt-country acts and the long tradition of singer-songwriters, rather than the denim and leather rockers whose songs she once played.

Clancy had come to musical maturity with a collection of often emotionally intense songs given colour and texture by a small core of sympathetic fellow musicians.

Her ‘Lucky One’ album showed an artist at the top of her game first time out.

“They are all very personal songs,” she said, “and it can be embarrassing. There’s the song ‘And So It Begins’. When I was singing that I was crying my eyes out, it was hard having it all out there.”

With lyrics which were refined and considered (“practice pushing the ‘what if’ away, walking bereft in this solemn brigade”), and instrumentation which moved from gentle acoustic guitar to swelling Hammond organ and kicking electric guitar, Lucky One showed an artist at the top of her game first time out.

“When I was about six or seven I wrote a journal and had pictures of myself with a guitar. I knew what I was going to do, which is exactly what I am doing now at age 32,” she said at the time.

“I’d tell a couple of my friends and get laughed out of the room, like, ‘Aww, she thinks she’s cool and is going to be a singer’. But I knew it then and would go to sleep thinking about it.”

She toured and recorded again, three years later releasing Magnetic which drove even deeper into her personal poetics, and which she co-produced with Andre Upston.

That time out there were strings (on ‘Join the Chorus’, ‘Southern Cross’) and horns (‘You Ain’t The Worst Mistake I’ve Made’) and Clancy played dulcimer, mellotron, piano, guitars, Wurlitzer organ, glockenspiel ...

It’s a measure of the high regard in which she was held that Warren Maxwell (TrinityRoots, Little Bushman) provided the haunting vocals on that standout ‘Ghost Town’, the late Aaron Tokona played guitar on ‘When I Do’, Nick Atkinson and Tim Stewart (Hopetoun Brown, Supergroove) played horns, and the strings were arranged by Bruce Lynch.

Tracks from it were played on the Australian soap Home and Away and in 2020 the album got a belated US release. But then, after a few years, Clancy disappeared off our radar to try her hand in New York. And by her own admission, it knocked her back and sideways for a long time.

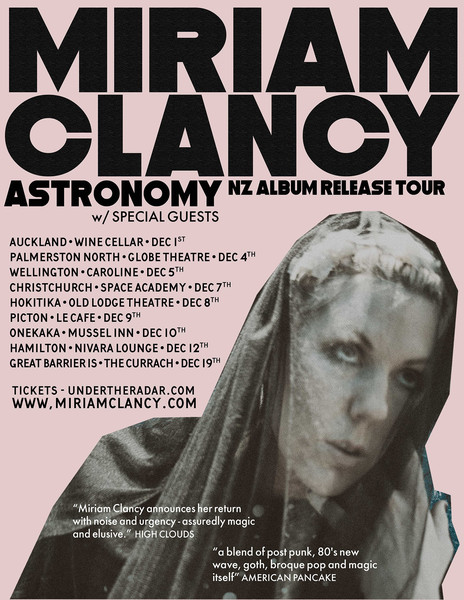

But a very different Clancy, one tested and toughened by those years, emerged with her new album Astronomy (2019), which pushed into rock and electronics.

And as a performer, when she played at Auckland’s Wine Cellar late that year at the start of a short national tour, an impressive transformation took place.

On stage with her “box of robots” – drum loops and programmes – and a small battery of guitar pedals, she delivered an often full-throated and sometimes brittle set which came with expressive hand gestures in the manner of Nick Cave, sometimes set up sonics akin to early 80s synth-pop and was punctuated by seductive ballads such as ‘Over You’ from the new album.

It was a compelling solo performance, just what the Astronomy songs required. Like Aldous Harding and more recently Reb Fountain, Clancy broke free from that space behind the microphone stand and strode the stage with exceptional confidence.

“I know there’s a lot of electronic stuff on this record,” she told me the next day, “but I like to venture into a heavier territory and a wider canvas.

“I got really frustrated with the acoustic thing, which I love and will be incorporating again. But I find it frustrating. I heard people saying there were too many women acoustic singer-songwriters in New Zealand,” she laughed, “and I was like, ‘Yeah, okay. But that’s not all I can do’.

“So this album is different and I like the wider scope and broader vision within the landscape I’ve made for myself, and how far you can push creatively.”

She has a band back in New York but enjoys the risk of performing solo with her portable technology. “It’s a house of cards, when it works it’s exciting, when it doesn’t it’s a soupy mess of wrong beats and overbearing guitar.”

Most of the songs on Astronomy recorded in New York – “about heartache, grief, loss, existential crisis” – had been written before Clancy, her husband and four children arrived there. Inspired by time spent on Great Barrier Island, the album’s title and sound reflected her emotional experience of the night sky and the millions of stars visible in that Dark Sky Sanctuary.

On the ground in new york, the city was tougher and more expensive than they expected.

“It would wrap around you and lift you into the cosmos. It’s amazing how something so far from Earth can affect us and give a sense of perspective… it’s the great equalizer.”

But on the ground in NYC, the city was tougher and more expensive than they expected and she stopped playing for a year.

“I fell apart a bit and needed to rethink everything. It was a depressing time. I had this album I loved and didn’t know what to do with. And we needed money, and I needed to look after my kids as well. So I needed to stop.

“The doors weren’t really open and it was a lot of hard work. I had grossly underestimated how hard it would be. I spent a lot of time in a tiny railroad apartment in Queens surrounded by people who didn’t want to talk to me, because I didn’t speak Spanish. I felt like an alien even though I’d got my Green Card for ‘extraordinary ability’.

“I was very depressed. I fell apart after making the album and I think I needed to fall apart to build back up. Hannah Gadbsy, the American comedian, says it well: there is nothing more dangerous than a broken woman who has put herself back together.

“I do feel a bit of that. It was depressing. I was depressed. I felt like an exile. I was isolated. It’s been a hard five years but we survived, and the kids are happy for having had some mum-time.”

After the hiatus however she attended open-mic nights and met others also trying to crack it. “I took out my guitar and trundled my little amp around and did a little open-mic-nights, and spent quite a bit of time at Sidewalk Cafe.

“I got to meet a bunch of really humble people trying to crack it and who probably never will. But they were happy with their own company and each other’s company and it was more about creating their art and having a place to do it.

“I’d get up and do one song and then I’d hang out. I did quite a lot of that until I realised, ‘What the hell am I doing?’ It was great but I’d forgotten how good I was. That sounds really arrogant but what had become quite a great thing to run songs had actually become self-defeating. I needed to pull my finger out and do things the right way.”

Among those things was her song ‘Ex Erebus’ played at the 40th anniversary commemoration of the Erebus disaster in 2019. Clancy is the niece of crew member Marie Wolfert who was among the 257 who died in the Antarctic.

And because she felt she hadn’t been in control of the direction of previous albums, Astronomy would be entirely her call.

“It was already in the sonic territory I wanted it to go, I had the basis of everything laid out and wouldn’t kow-tow to others’ opinions. I went out of my way to be unshakeable. I handed my producer the songs and said, ‘I know what I want and here it is’. And that’s what I got.”

And now things are looking up on all fronts. They are home-owners in Kutztown, the children are settled, New York is a manageable two-hour trip away, her husband has regular work there, and she has a band, bookings and is recording new songs for another album. “Astronomy took an embarrassingly long time so we want to follow it up really fast.”

And – although she bought a Hot Cake guitar pedal while back home – it won’t be like Astronomy’s electro-rock template?

“No, I don’t always need to do that, I’ve tried it ... so let’s see what happens next,” she said in late 2019.

And sure enough her 2020 single ‘The Thief’ was an atmospheric, acoustic-based ballad written and recorded in isolation, with all profits going to the New York charitable advocacy and direct service organisation, The Coalition for the Homeless.

The woman who witnessed and understood the ‘Ghost Town’ lives, and is still out there observing, writing and recording songs of power and empathy.

A new album is imminent in 2021.