The Secret Musicians’ Ball

It was mostly a simple office job. There were two breaks from this drudge, one was organising the annual Musicians’ Ball at the Peter Pan Cabaret, which involved asking about six bands to appear. There was a lot of kudos in performing at the ball, and one year we had an application from the South Seas Island Serenaders who – although on our books – I knew nothing about. I wrote and asked them for information on their personnel and background, and got no reply, so I called Bill Sevesi, the very well-known and respected Polynesian bandleader. He was very guarded to say the least and the discussion went:

Me – G’day Bill, what can you tell me about the South Seas Island Serenaders band?

Bill – Weeell, actually some of them are my cousins …

Me – Fine, Bill, but are they any good?

Bill – Weeeell they practise a lot …

(It was becoming clear that Bill had some reservations about them, but was being “staunch”.)

Me – Now, come on Bill, I need to know if you think this band is good enough to stand up at the Muso’s ball along with Arthur Skelton’s Band, the Radio Dance Band, Merv Thomas’s Dixielanders and so on …

Bill – Weeell actually Neil, I am a bit surprised they applied to play at the ball really, because the last I heard, they had a big argument, and the drummer took all the band’s gears and lined them up in Crummer Road, and ran over it all with the van!

Egged on

A rather world-famous-in-New Zealand guitarist called Peter Posa came into the office. He sadly related how he had been sacked for misbehaviour from the El Matador Restaurant, and wanted to get his job back. It seems he had an argument with the chef, and as a result he got sacked. I ascertained that the argument arose when Peter went in to get his meal, and the chef had closed down the kitchen. “Did this argument involve any fighting Peter, For example did you hit him or anything?” “No, No,” said Peter, “I never hit him.”

Tom Skinner had always urged me to remember that you can’t buy an ice cream with a penny with a picture on only one side. Only a penny with a picture on each side, different to each other, is worth anything. This had proved wise counsel in the past and would again as I asked the owner what happened. He explained in his thick European accent that Peter had to get his meal before 10pm when the kitchen closed, and when he went in at 10.15pm the chef wouldn’t serve him, “So Peter complain that he have to play requests, then he throw a dozen eggs at the chef and cause a great mess.” “So,” I said, “Let’s be clear, Peter gets in a row, and picks up a carton of eggs and throws … ? “NO, NO, Mr McGough, not a carton, ONE AT A TIME!” Peter wasn’t reinstated, but he had told the truth, he indeed hadn’t hit the chef, not even once from 12 shots.

Post Office in show business

Negotiations with the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation were simple: they had a clause in the Broadcasting Act that exempted them from the Industrial Relations Act. They had previously been part of the public service, so it was deemed convenient that their staff remain as members of the Public Service Association (PSA). The result was that the Musician’s Union was left out the rain. Broadcasting could ignore us if they wished, and it is to their credit – and the good relations established by Sir Tom Skinner over many years – that they didn’t.

Neil McGough at Auckland Town Hall

We arrived at Broadcasting on one occasion with Julian Lee as an assessor. We had three negotiators, and they turned up with seven, so we complained of “cheating” of course. Julian had our submissions in braille, and added greatly to the humour with asides like, “Just kick me Neil when you need me to fall off my chair for the sympathy vote.” At one stage he became a bit agitated during a discussion of how long it took to write a page of music for the violin. No computers in those days of course, and all music was written out by hand. After flashing his fingers across his braille book and rattling off figures and times he himself had compiled, he suddenly slid his braille book across the table at the chairman with astonishing accuracy, and shouted, “And if you don’t believe me, FEEL THAT!”

Julian, being blind, hated being treated as if he were deaf as well. Coming home from these negotiations he and I were seated in the front seats of the aircraft as he was considered “handicapped”. As we did up our belts, the air hostess leaned over Julian and asked me, “Will your friend require any assistance when we land in Auckland?” Julian replied in a loud voice, “How dare you madam, he hasn’t drunk as much as all that!”

Broadcasting paid less than the general award for their programmes, arguing that they could only play them once with no financial return, whereas anyone else could sell records, and reuse as they liked. I always argued that this was an artificial argument because there was in reality no reason why they could not use recordings as repeats many times over. In the end I had a tough job persuading both Broadcasting and the union members that we could get more money if we wrote into the agreement that radio and TV could broadcast material twice. The second broadcast would almost certainly be in an off-peak time, so rather than compete with ourselves we would only be competing with such American classic reruns as Petticoat Junction or Mr Ed.

In those days Broadcasting was very public service in attitude, and it must be noted now that they could well have pointed out that it would be hugely cheaper to put on an LP of the Glenn Miller band than record and broadcast a local radio orchestra. But they held the belief that as a public service they had a duty to local artists, and as much as they could they lived up to that. Light orchestras, drama, jazz groups and recitals from classical singers and so forth were regular staples on radio during those years. Of course immediately they changed the structure and “profit” entered the Broadcasting language, all that ceased. No more radio orchestras, or anything of the kind.

When our sign writing company was up and running in the 1980s, I had a call from a sales director of Radio New Zealand, who wanted us to sign write one of their cars. She came to see me and we chatted about Broadcasting. To my surprise, she had never heard of Ossie Cheesman, or any household name bandleaders or musicians from only a decade before, and was unaware that Radio New Zealand once had a radio theatre which could broadcast shows with a live audience. Now – in the 2000s – RNZ does not even own a studio they could record and broadcast an orchestra, it was demolished about the same time as His Majesty’s Theatre was demolished in the 1980s. I guess we were lucky to be around when it was “all happening man” because now musicians get almost no work at all from radio and TV which is supposed to “reflect New Zealand culture”.

Billy T James and the core cast and orchestra of TV's Radio Times, with Neil McGough at back

Television however, was a growing industry in the 1980s. Although now there is almost no local light-entertainment music content, it was for the 1970s and into the 80s, a growing and flourishing part of our work. In 1975, NZBC-TV had been divided into two parts, Television One in Wellington, and South Pacific Television (TV2) in Auckland. Kevan Moore was the producer of light entertainment in Auckland for SPTV, and Bernie Allen was appointed resident musical director. After the success of C’mon they started out with a plan to produce a series of shows featuring local groups from rock, opera, jazz, and other different idioms in each series, but the huge success of the first season of Happen Inn in 1970 caused them to stick with the format and Happen Inn became a regular primetime show on Saturday night for many years. Singers such as Tommy Adderley, The Chicks (and later Suzanne Donaldson as a solo artist) Ray Woolf, Ray Columbus, Shane, Dinah Lee, Rob Guest, Angela Ayers and others became household names after appearing regularly on shows like Happen Inn and C’mon. At that time, there was also a flourishing nightclub scene throughout New Zealand, and having these stars appear at such clubs added greatly to their earning power. Even Kiri Te Kanawa had plenty of club work at that time. It may have been the only time in New Zealand when we had a flourishing industry for such entertainers. In the early 1980s, shows such as 12-Bar Rhythm ’n Shoes appeared as the sun set on New Zealand television’s light-entertainment productions.

Redwood riot

In 1970, backing Robin Gibb of The Bee Gees, we performed the shortest concert ever. Phil Warren hired Redwood Park at Swanson, an outlying West Auckland suburb, and staged Redwood 70, a sort of mini rock festival featuring Robin Gibb in the evening. I had put together quite a large orchestra, the rehearsals went fine but the concert didn’t.

Robin’s big hit at the time was ‘I Started A Joke’ and the concert was to start with this. By the time the concert started, about 8pm, the large crowd had been partying all day and was a bit dodgy to say the least. We started the intro, and after a few bars, Robin ran on stage and launched into “I started a joke, which set the whole world laughing ...”

A small wave of girls charged the front of the stage, screaming and carrying on as girls at pop shows did, and a row of burly security men threw them back where they belonged. This seemed to irritate the audience, especially the girls’ boyfriends, and there followed a general charge by hundreds at the stage. They flowed over the front in a swirling battle with dozens of security men, who were all swamped in the deluge, and a mighty brawl began on stage. Beer cans flew as the audience at the rear did their best to contribute to the proceedings, and a brave TV cameraman walked round, stepping over the struggling bodies, taking shots for the night’s TV news. “But the joke was on meeee / Oh noooo...” sang Robin, but about then he gave up and headed for his security van.

You remember in Roadrunner cartoons how characters would run off the top of a cliff, and keep running until about three metres out from the edge? Then they look down, look worriedly at the viewer for a second, and plunge to their doom? Well Robin Gibb is the only bloke I ever saw who actually did that. He ran off the end of the stage, in midair with his little feet still going like mad, and finally landed about three metres from the bottom step. Into the van! Slam! Gone!

Meanwhile on stage the brawl continued. Bruce King broke the world record for dismantling a drum kit, and the rest of the band got out of there, holding their valuable instruments over their heads. In the midst of this rumble I stood at the rear, sort of supervising, when the second trombone, Neil Dunningham, tapped my shoulder and shouted, “Would you tell me when we get to letter ‘B’ because I have lost count.” “Never mind,” I shouted back, “I don’t think we are going to get to letter ‘B’.” So we both laughed, and left hurriedly.

We then repaired to the Musician’s Club and spent the evening laughing at the shortest concert we ever played. What’s more, we pointed out to Phil that he already had the gate takings, so we were paid in full. That was nice.

Piper’s farewell

In the mid-1970s I was asked to fly to Dunedin and repeat one of the Rock Symphonic concerts with the Dunedin Civic Orchestra, to raise funds for the refurbishment of the Regent Theatre. In Dunedin the shortage of experienced recording musicians made the local orchestra struggle a little, and a shortage of strings compared with Auckland also caused a lot of balance problems.

After a very successful concert in which Calder Prestcott’s Dunedin Big Band performed the first half, the mayor had a small reception to thank me for my work, and presented me with a huge half-gallon of Hundred Pipers whisky. I asked him, “How in God’s name did you know I was a whisky drinker?” He replied that when he saw me at rehearsals he thought, “I know that guy, where have I seen him before?” Then he realised that he was in the bar of a certain licensed establishment some years before, when John Rowles and I strolled in, sat at the bar and began to sample all the whiskeys that you could not buy anywhere else in the country. John and I finally settled on Hundred Pipers as the best, so the mayor thought it a most apt gift. I of course agreed.

The trouble was, for the next few months, whenever Harry M Miller’s New Zealand manager took to threatening to sack people, cancelling rehearsals without notice and things, to force me to declare a dispute, out came the Hundred Pipers. So in the end Dunedin’s scotch was all drunk in the cause of “better industrial relations within the classical music sector of the entertainment industry”.

Harmonica blues

For some years Bernie Allen, the musical director at TVNZ in the 1980s, had been trying to persuade me to resume some playing work, and I had resisted fiercely. He called one morning however, and started to rabbit on about my “forthcoming performances on TV with Patsy Riggir.” Only having a vague recollection of talking with him about Patsy over a bottle of whisky the night before, he advised that about half past two in the morning I had thought it was a great idea to fly to Christchurch and appear as a guest artist on the harmonica, with the very well-known country star, to be recorded before a live audience in the James Hay Theatre.

Neil McGough adds some harmonica to ‘Stardust’ as a guest on Patsy Riggir's Christmas TV special, 1985

To ensure I didn’t do a runner, he had already talked to the producers, who were very enthusiastic. I would get all expenses and about $400 for the appearance, and I then found that a new harmonica would cost $385, so I clearly wasn’t going to make anything out of this. After a lot of listening to tapes I chose for the first show a number called ‘Cotton Eyed Joe’, a rollicking flat out “hoedown” sort of thing, wrote a lead chart of how I wanted to play it for Bernie to complete the orchestration, and set to work to master this rather difficult piece. Another score was produced for me to accompany Patsy in a blues type duet, ‘Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song’.

In Christchurch when we rehearsed ‘Cotton Eyed Joe’, we found that I had sped it up considerably from the recordings we took it from, and to everyone’s annoyance it lopped about a minute off the show. When we did the blues number, I used three small “blues harp” instruments in the three different keys of the arrangement. This required that I remember very carefully in which pocket I put each one, and sure enough at the dress rehearsal, I whipped out the wrong one at one point and sailed confidently into my bit in the key of G while the band played the same thing in E flat.

This combination doesn’t work very well, and as the band crumpled to a wilting stop under Bernie’s baton, I resorted to the old dictum of “Getting your kick in first” and complained loudly that the band was horribly out of tune, and would Bernie please fix it before we taped the show. After the laughter had subsided, and I had convinced Patsy that I wasn’t as bad a player as it seemed, we started again and from then on I got the pockets in the right order.

For the last number the producers very tentatively asked how would I feel in a Santa suit, as the song was about Santa. My bodily silhouette is similar to Santa’s, but as I say, “when you are watching your weight, it is handy having it right out front where you can keep an eye on it!” However the rest of me isn’t a bit like Santa, so I asked, “Have you blokes ever tried to play the mouth organ with a Santa beard on? Bernie has a real beard and it gives him enough trouble playing the bloody saxophone. So forget it!” That suggestion was dropped.

Watch Neil McGough perform with Patsy Riggir

A fortunate life

I am often asked, “Wouldn’t you like to do some music work again?” and my answer is always a resounding “NO!” For a start I would have to practise again. One good thing about the harmonica is that it is the only instrument I know that you can practise lying down! Lying down is already one of my retirement hobbies, at which I am most adept, but with the trombone you have to be at least sitting up, and even standing most of the time. Such behaviour is against all my current principles.

What I did in the past was what I wanted to do at that time. I have moved through many phases of life and music, and been most fortunate in the mentors I worked with. I have also numbered many hugely talented and honoured artists among my friends, and enjoyed musical experiences few have had the fortune to enjoy. I have no complaints.

I was also fortunate that my early life in Auckland, the fifties through the seventies, was full of musical activity. Radio and TV orchestras, continuous live theatre work, session recording for LPs and commercials, dance hall work and touring with international stars, all or most of which are now gone.

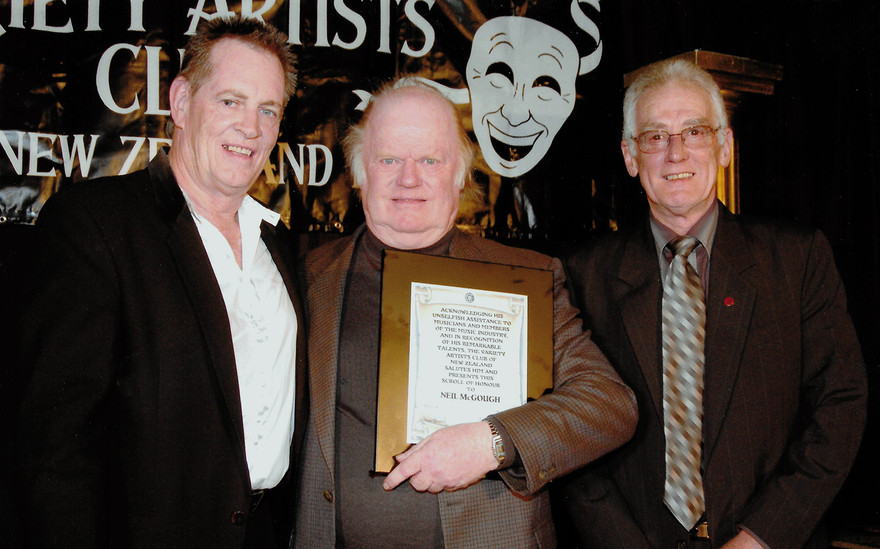

Neil McGough receives a Variety Artists Club scroll of honour in 2005, with club president Tom Sharplin at left, and broadcaster Jim Sutton. - Neil McGough collection

I don’t seek to complain or criticise the tastes of people today, but to point out the effects musical changes have had on the ability of musicians to earn a living. It is ironic that one area of music where an instrumentalist can still enjoy some stability, and not worry that changes in pop fashion are going to put him out of work for life at any moment, is so-called classical music. For a trombonist, who is not part of an orchestra anyway until it is pretty large, the NZSO and the regional orchestras remain the only stable line of employment available in New Zealand. A TV gig once or twice a year, or jazz festival concert and a couple of pub gigs are not going to pay the grocer next Thursday.

We live in a world which adores fame and money. We pay TV newsreaders three times more than the prime minister! Women’s magazines are loaded with stories about film and TV stars and their babies and love life. We admire the rich: why? In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar the murderers are asked why they killed Caesar and they reply, “Because he was ambitious!” In ancient days, ambition was a vice like greed and lust. Happiness and sadness are emotional conditions that come and go according to current circumstances. Plato defined “happiness” as “contentment within your allotted station.” Contentment is the state I seek.

Beware of ambition. The very word implies dissatisfaction with your present station. Contentment is hard to achieve if you want to be famous and you’re not yet; if you want to be rich and you’re not yet. As I said earlier in this book, look over your shoulder at all those thousands, millions of people who aren’t in the Woman’s Weekly because they are not rich or famous. For every star you see, 10,000 failed.

At a funeral for a musician friend recently I talked with Al Fletcher, a guitarist mate from way back. As I left I said, “Well Al, I hope I see you at the next funeral.” “Why?” he asked. “Because it will mean neither of us has died yet.” With reasonable health and a sense of humour intact, what more could I want?

--