While his former bandmates were receiving a standing ovation at the APRA Silver Scroll and joining in on an ad lib ‘E Papa’, Fonoti was at the bedside of his son Noah, in a coma in an Auckland hospital, where he stayed while Noah recovered.

Fonoti’s transition from poet to songwriter with such anthems as ‘Dragons & Demons’ and ‘French Letter’ set Herbs on a path as one of the country’s most important bands.

Fonoti’s transition from poet to songwriter with such anthems as ‘Dragons & Demons’ and ‘French Letter’ set Herbs on a path as one of the country’s most important bands, melding politics and melody and never surpassing his one official release with them, Whats' Be Happen?

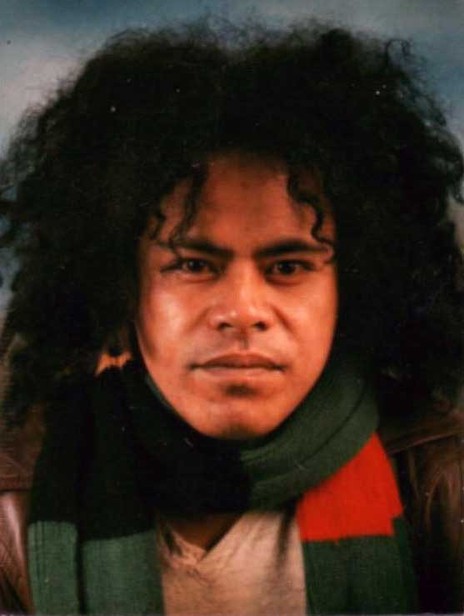

Toni Fonoti was born to Samoan parents in Wellington on June 3, 1953, but grew up in Ponsonby, Auckland, to the sounds of his father’s Nat King Cole, Bing Crosby and Hollywood musical records. Polynesian music was also played – although Fonoti knew enough to sing along, he never learnt to speak any Pacific languages.

He fell under the spell of The Beatles while still at primary school and moved on to songwriters such as Bob Dylan, Cat Stevens and then Jimi Hendrix as he progressed through secondary school at Mount Albert Grammar.

Purchasing all the latest fan magazines, Fonoti and his mates were the rock music gurus at high school, able to answer any questions from their fellow pupils on who sung what and which brand of guitar they were using.

That information didn’t impress the girls, though, and Fonoti began to dream that one day he would be on stage, all of those girls would be screaming and he would be famous.

Taking up the drums, Fonoti formed a high school band of Polynesians covering the likes of The MC5 and The Stooges. They were never as popular as the other Mount Albert Grammar band based around the Clarke brothers that would evolve into bona fide pop stars The Challenge.

The school connection led Fonoti to Auckland clubs where he watched The Challenge and the likes of Human Instinct, Sonny Day and Rangi Williams with The Arch. Fonoti would hang around and badger the musicians as they set up.

Armed with knowledge gained from the music magazines, he would ask, “What sort of equipment do you use? How do you get started?” Quite often the response was, “Piss off and get your own band.”

Older stepbrother Tony Hoskins was an influence on Fonoti when he turned up to stay with the family. Complete with Afro hair and silk trousers, Hoskins was in a band that played at the Taboo in the city. That and seeing Harry Leki with The Simple Image and Reggie Ruka with The Classic Affair opened Fonoti’s eyes to the fact that Polynesians could be in bands that made the charts. What puzzled him even then was that few of the Māori or Polynesian bands on TV or in the clubs and pubs were doing original material.

Fonoti met Dave Pou and Julius Schwenke at the Mormon Church and they formed a band called War. On one occasion they were paid $50 after two songs to stop playing and at a church dance had the power cut and were told to leave. The band’s fondness for swearing didn’t help.

Upon leaving the Mormon Church, Fonoti discovered alcohol and marijuana, drummed in The Peter Edwards Memorial Band and The George Brown Band and was picked up several times for being drunk and disorderly, spending the odd night in the cells. He stayed six weeks on remand in Mount Eden for possession of an ounce in 1977.

While locked up he decided to turn his life around and upon release moved to South Auckland, drumming in three-piece Jo Blo with Dave Pou on bass and brother Pere Pou on guitar. Throwing in their day jobs to focus on playing music, they covered 1960s and 70s soul through to Bee Gees disco.

In the months before Bob Marley’s 1979 Western Springs triumph, Fonoti was switched on to reggae music by his youngest brother Brian and his mates. They would come to Fonoti with the early Marley records only to be turned away with, “I’m not listening to that crap. You listen to Marvin Gaye.” When they eventually broke through the older Fonoti’s defences, he was struck especially by the music’s message.

His new plan was an original reggae/R&B band with a Pacific flavour and he set about seeking out the top Polynesian players in Auckland to ask if they wanted to join this new band. Guitarists Tuhi Timoti and Tama Renata were two of the many who sent him packing.

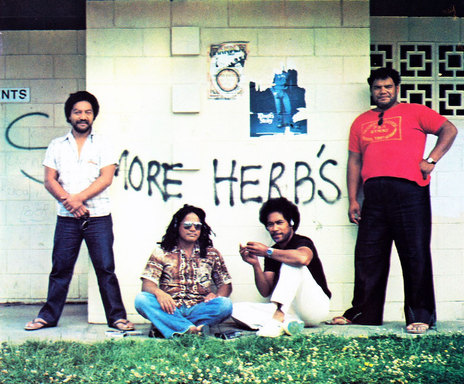

But there were some who said yes. Dave Pou was up for it and Fonoti swapped to congas after he found drummer Fred Faleauto in the resident band at the Rob Roy Hotel in Freemans Bay. While working cleaning caravans, Fonoti also found interest from co-worker Spencer Fusimalohi, who played guitar. Thus was born Backyard.

Fonoti was also a casual member of friend Tigi Ness’s band Unity. Although Fonoti had always written poetry, he wrote his first song, ‘In The Ghetto’, with Ness and Danny Wilson. A version of the song appeared on a Herbs LP after Fonoti had departed.

Backyard had the opportunity to do some recording and, with a lack of original material, Fonoti put forward Jimmy Cliff’s ‘The Harder They Come’ and ‘You Can Get It If You Really Want’. Although not confident in his vocal ability and having sung no more than harmonies to that point, the rest of the band pushed for him to sing lead.

Backyard would play early evenings at the Trident in Onehunga and till the early morning up the hill at Neil’s Club. They were soon joined by guitarist Dilworth Karaka, and an early supporter was Polynesian Panthers co-founder Will ’Ilolahia, who had the same idea as Fonoti – a Polynesian band playing their own songs.

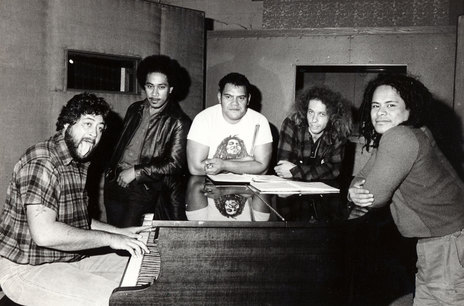

They started rehearsing a fully original repertoire, attracting Mascot Studios owner Hugh Lynn, and recording demo after demo as they went. Fonoti would arrive with a sheet of lyrics, sing the melody to the rest of the band, arrange the song and commit it to tape.

By the time they had renamed themselves Herbs, the band burst onto the national scene.

By the time they had renamed themselves Herbs, the band burst onto the national scene with a super-tight original set at Sweetwaters and as support for Stevie Wonder in 1981. Their six-song mini-album Whats' Be Happen? was released that July.

It included Fonoti’s commentary on the role of the Church in Polynesian life ‘Dragons & Demons’, his observation of the police fear of brown skin ‘Whistling In The Dark’, the lament of Pacific Islanders living in New Zealand ‘What’s Be Happen?’ and a tribute to the late Bob Marley, ‘Reggae’s Doing Fine’.

The record was a critical success and Herbs found themselves playing at 1981 Springboks tour protest rallies as well as scoring the support on British reggae band Black Slate’s New Zealand tour.

With his lengthening dreadlocks, Fonoti wanted to be part of the burgeoning Rastafarian movement in Auckland. But he felt like a fake when involved in deep conversations about Rasta philosophy with Black Slate singer Keith Drummond.

Fonoti studied books about the movement and found his interest in Rastafarianism was at odds with the approach the rest of Herbs were taking. When it came time to sign a new management contract on the eve of their first Pacific Islands tour, Fonoti broke the news he couldn’t stay with the band and remain authentic to his beliefs.

He headed north to Matarau, gave his car to a farmer and his family, and looked after the farmer’s marijuana plantation. After three or four months of watching the plants grow, he arrived one day to find all of them had been stolen.

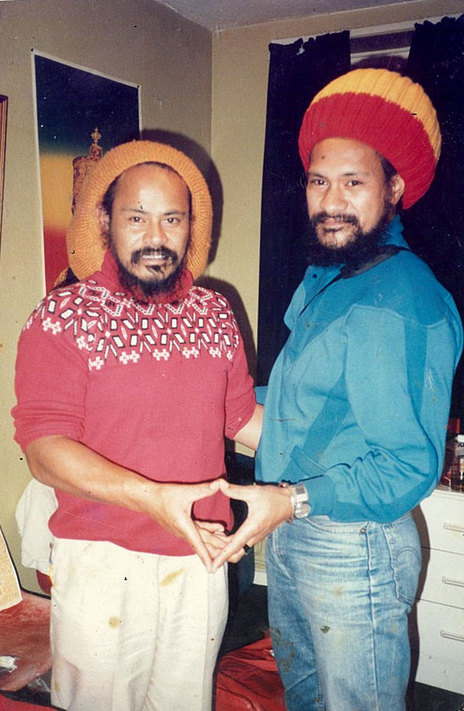

He returned to Auckland and became a high-profile member of the 12 Tribes Of Israel chapter being formed around Tigi Ness and Jamaican Hensley Dyer. Fonoti was instrumental in setting up the 12 Tribes Of Israel band that would travel the North Island attracting followers to the movement.

It wasn’t until later that Fonoti realised some of the demos he’d sung with Herbs before quitting had been finished and released on their second mini-album Light Of The Pacific, including the band’s first chart entry ‘French Letter’ which he’d written upon a suggestion from Mascot engineer Gerard Carr.

After 10 years and several DIY cassettes with the 12 Tribes Of Israel, during which he taught himself to play saxophone, Fonoti and his brother Brian started the duo Simon & Fire, performing standard covers in a reggae feel just for fun.

They released an album of their own songs (one written by Brian) called Aroha, which included a reworking of ‘French Letter’, and scored a residency at the Sheraton before packing up their families and heading to Brisbane in 1996.

After initial struggles with no transportation or agent interest and a period busking in Fortitude Valley, Simon & Fire started working steadily right up until Brian left for a job with an auto parts chain in 2000 and Toni turned solo. Brian Fonoti passed away after a sudden heart attack in 2010.

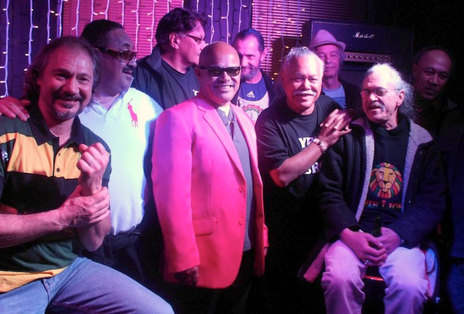

When the call came that Herbs were to be inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame in 2012, Fonoti was surprised how entrenched the band had become in the country’s psyche beyond the Polynesian and reggae audiences. He hadn’t even owned a copy of What’s Be Happen? until 2011 or so.

He headed to Auckland with his two sons and daughter for the ceremony and was feted at a reunion of former Herbs members the night before. But in the early hours, he received news that his son Noah had been shoved to the ground, hitting his head on the footpath and was in a coma in hospital.

The induction was quickly forgotten as the Fonoti family stayed at Noah’s bedside for the next six weeks as he regained consciousness and made a full recovery, Herbs rangatira Dilworth Karaka and the music industry providing greatly appreciated support.

Toni Fonoti is still writing songs and honing his craft. He and his sons, Noah and Yacob, play music around Brisbane in different configurations and Toni Fonoti is still visualising success.