He also started writing his own material and quickly became known as someone who could take a local image and turn it into a universal truth. He described an IGA store closing down. The Waikato River as a life-giving – and taking – force. The romantic fantasy of a well-known neon light. A slacker wishing he could go fishing. A pub entertainer sentenced to a lifetime of singing cover versions.

Ironically, the song which introduced most New Zealanders to Hunter was an advertising jingle.

Ironically, the song which introduced most New Zealanders to Hunter was an advertising jingle for an insurance company, ‘There’s a Blue Sky Waiting For Me’. In 1991 an ad agency wanted a song that emulated Willie Nelson’s ‘Blue Skies’, which was unavailable; Hunter is no impressionist, but happens to be a Willie Nelson scholar. The opportunity to create a homage became a great calling card – the voice, if not the singer, became nationally known. It had taken Hunter nearly 20 years to have the motivation and material to record his debut album, Neon Cowboy, in 1987, and now he quickly completed two more in just half a decade.

Country music was where he got started with music. At the age of eight, in 1958, he was home from school, suffering from chicken pox. He lay in bed listening to the family radio, and had an epiphany when he heard George Jones singing his honky-tonk classic ‘White Lightning’.

Recalling his childhood years later, Hunter knew he had the perfect background to be a country singer. He grew up in Pukemiro, a Waikato mining village 15 minutes southwest of Huntly. Alan Hunter was the son of a miner, and just eight months old when his father died of work-related illnesses. But he inherited music from his father, who had been a pianist playing Saturday night dances in local halls with pick-up bands. Hunter was the youngest of seven children, and there was a pile of 45s in the house: Elvis EPs, Fats Domino, Little Richard. A neighbour let the children play his 78s of Hank Williams and Hank Snow.

Shortly after hearing ‘White Lightning’, the eight-year-old was encouraged to sing at local gatherings: Elvis, the Everly Brothers and Frankie Lymon’s high-pitched hit ‘Why Do Fools Fall in Love?’ The budding child singer quit when he was 11, but later the emergence of The Beatles made him reconsider. At 14 he won a school talent quest singing their version of ‘Long Tall Sally’. While a teenager, hearing the British blues of John Mayall and Cream, he dreamt of moving up to Auckland.

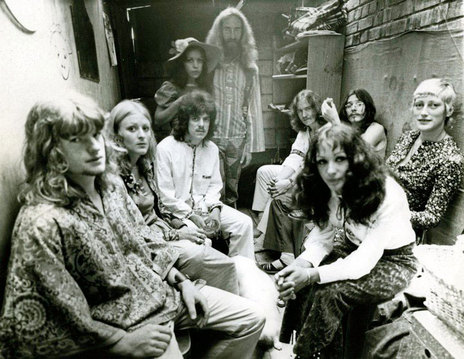

Hunter arrived in the big city aged 19, just as the 1960s came to a close. Clubs such as the Bo Peep and the Galaxy were pumping with acts such as The Underdogs and The Action. He got a gig singing with the hard-core blues band Killing Floor, in which the fiery guitarist Henry Jackson fronted twin saxes. University audiences were impressed by their dedication, and the way they captured the sounds of Buddy Guy and and Otis Rush. In the 1970s, Hunter led Cruise Lane, a country-rock band styled after Delaney & Bonnie, Van Morrison and Leon Russell. Among its members were guitarist Red McKelvie, who could put the twang into pop, and pianist Paul Hewson, later a pivotal member of Dragon.

Cruise Lane held court at the Embers, a downtown Auckland club run by folkie Nick Villard and frequented by inner-city bohemians. Hunter recalled the scene to Real Groove: “Flasks of whiskey under the table, and everyone there, from transvestites to Korean seamen to American GIs on r&r. A great, great club. Chewing gum stuck to the carpet, real sleazy.” The band also supported overseas acts such as Daddy Cool and Mungo Jerry. After 18 months at the Embers, Cruise Lane made an ill-fated foray to Melbourne, where they got few meals and even fewer gigs.

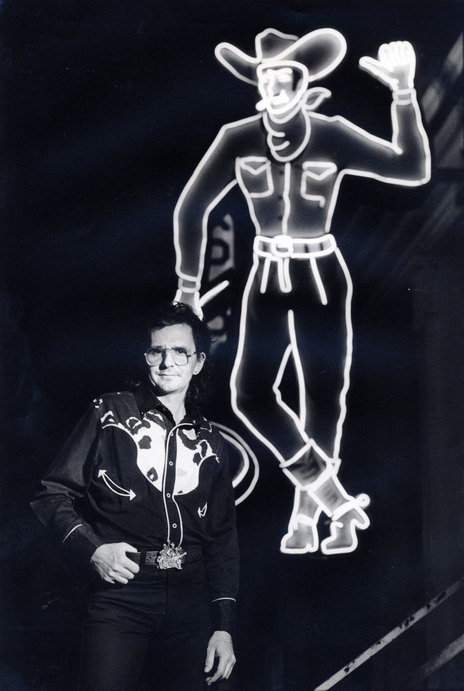

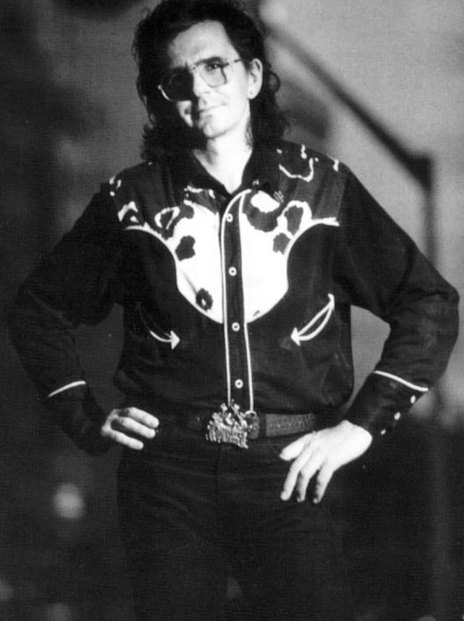

Wearing a big hat in the big city wasn’t easy; he often felt as alien as Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy.

Soon, Hunter was back in Auckland, and fronted Chapeaux at the Crypt, on Queen Street, from 1972-1974. By now he had latched on to the funkier, country-influenced styles of Little Feat and JJ Cale, and Leon Russell’s tribute to classic country, Hank’s Back. Chapeaux also won some high-profile support slots: The Faces, the Amazing Rhythm Aces, and Hunter’s old hero Leon Russell.

But when the residency at the Crypt became more “cabaret than nightclub”, he quit Chapeaux. He spent a couple of years in the 1970s playing with Malcolm McCallum, while drifting back to his first love, country music. The influence of country-rock in the 1970s can be seen in all the bands he played with and supported, and the emergence of the “outlaw” school of country songwriters who turned their back on Nashville: Nelson, Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, Jerry Jeff Walker.

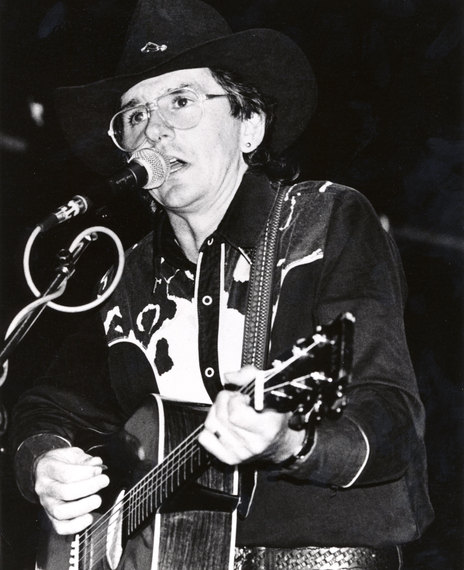

In 1981, he formed Hillman Hunter and the Rootes Group, a big country band that almost verged on western swing, and they began a three-year residency at the Royal International Hotel on Wellesley Street. (A hole in the ground since the late 1980s, the Royal was where The Beatles and other stars stayed when visiting Auckland.) Hunter’s Stetson was like a mission statement, and he had already won the respect of other musicians and many fans.

But wearing a big hat in the big city wasn’t easy; he often felt as alien as Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy. There was the occasional gig where playing country meant dying a death on the bandstand, and Elvis had to enter the building to keep the audience.

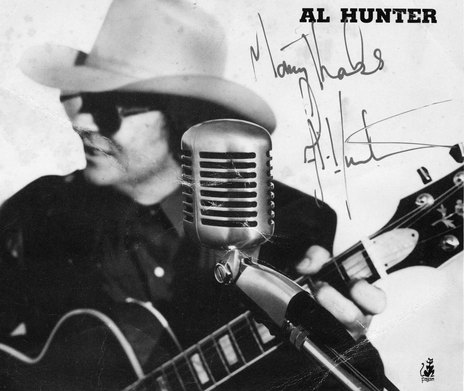

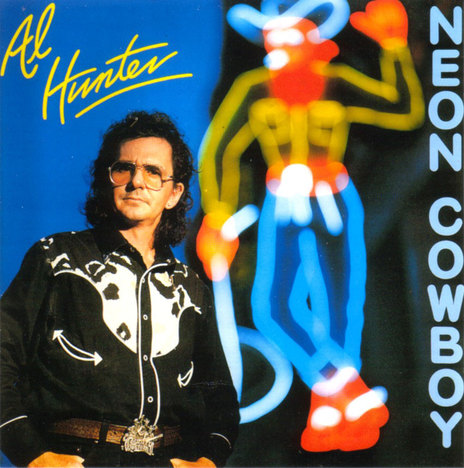

CBS offered Hunter the budget to record a single; instead they got an album of mostly original songs.

CBS offered Hunter the budget to record a single; instead they got an album of mostly original songs. Neon Cowboy was recorded and produced by former Chapeaux and Street Talk keyboardist Stuart Pearce in his Sydney home studio. The title track was firmly rooted in Queen Street, Auckland, where the Kean’s for Jeans neon cowboy sign flashed for many years. Neon Cowboy was released in 1987. It was a milestone in Hunter’s career, in a watershed year for New Zealand country music. A few months later The Warratahs’ debut The Only Game In Town came out, and it seemed that credible country-rock with a local flavour had finally arrived.

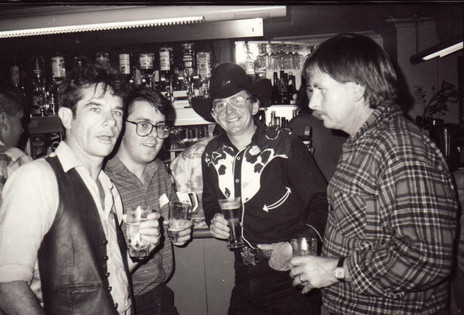

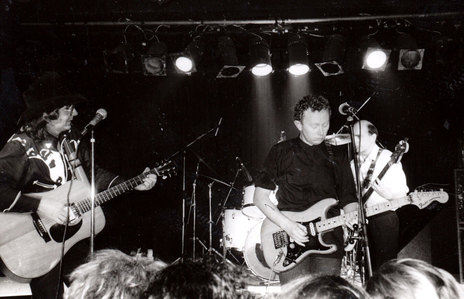

In 1990 Hunter was offered a regular Saturday afternoon gig at the King’s Arms in Newton Gully. At the time, “the KA” was a nondescript pub, hidden away on the edges of Auckland’s CBD, and the main music to be heard was the sound of the TAB in the public bar. For four years the Al Hunter Band held court in the KA’s lounge bar. Mixing the sound of a string band with country-rock, the group featured seasoned players such as McKelvie on guitar and pedal steel, drummer Bruce King, bassist Alastair Dougal and fiddle player Cath Newhook. It was a draw card for a motley crew of music lovers of varying ages and levels of sobriety; a World War II veteran shared the dance floor with hard-living identity Dolly Rocker, a rugby league prop beside a quiffed rockabilly revivalist. What they all had in common was Al Hunter who, like Epi Shalfoon at the Crystal Palace 40 years earlier, seemed like a personal friend to all those present. Apart from the show-stopping finale – a raunchy version of Elvis’s ‘One Night With You’ – the crowd mostly called out for Hunter’s originals.

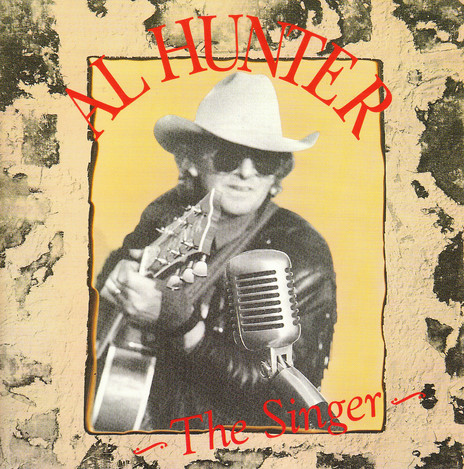

These were recorded for a Radio New Zealand programme in 1992, and came out the following year on Hunter’s second album, The Singer (it also included ‘Blue Sky’). The band knew the material so well and Hunter’s confidence had grown, so it was a leap forward from Neon Cowboy. The songs were about real lives, especially Hunter’s own. The man who sang ‘I Don’t Want To Go to Work Today’ stays awake with a bottle of Jack Daniel's to write ‘The Longest Night On The Shortest Day’. The title track is about a bar-room singer who writes his own songs but survives by playing those by others; he even obliges by singing ‘Happy Birthday’, and someone always demands ‘Me and Bobby McGee’. ‘Pukemiro’ is a serenade to his home town, and ‘The River Song’ a tribute to the mighty Waikato, the river that “runs through the country like an escapee”.

Shortly after The Singer was released Hunter relinquished his KA residency – and his band – and began to make forays out of town. For years, his friends joked, he had been touring Auckland “several times a week”. After experimenting running his own room with a new band at the Astor – a now-demolished pub on the corner of Khyber Pass and Symonds Street – he briefly returned to the KA. But with other bands now featured there – by 1995 the room began to replace the recently closed Gluepot – and the club-like atmosphere of those Saturday afternoons had passed.

For three decades Hunter seemed like a musical institution in Auckland.

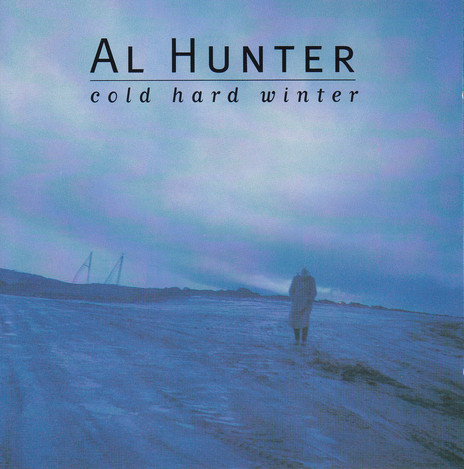

In 1997 Hunter followed up The Singer with Cold Hard Winter, an all-original set for Pagan in which songs such as ‘Slow Down Your Fall’, ‘Love’s a Thing Worth Fighting For’ and ‘Sleep Won’t Come’ shared the grittiness of the title track. Two songs were co-written with Arthur Baysting: ‘When The Circus Came To Town’, an evocative childhood memory of Pukemiro, and ‘Hall Of The Memphis King’, which harks back to that family valve radio “cutting the rug on the livin’ room floor”.

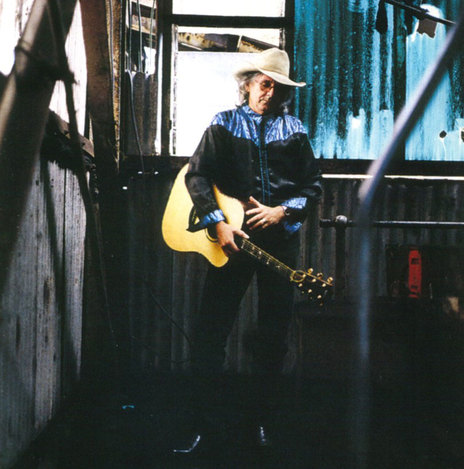

For three decades Hunter seemed like a musical institution in Auckland, a singer’s singer who determinedly wore a Stetson through many fashion changes. So it was a surprise to his followers when he suddenly left the big smoke in 1998 and based himself on the West Coast of the South Island. During brief tours after the release of The Singer, he had found a new musical community, very similar to the well-worn regulars at the KA.

Based in Hokitika he continues to perform in the region, receiving empathetic backing from musicians such as the Coalrangers from Canterbury, and the local father-and-son guitar aces Des and Dean Hetherington of Hokitika. He remains dedicated to country music, songwriting – and still wears a Stetson hat.