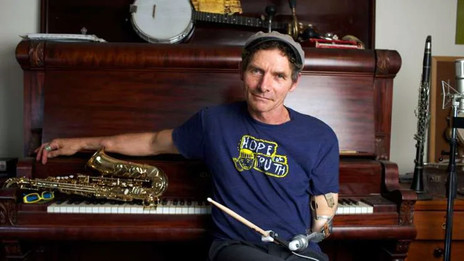

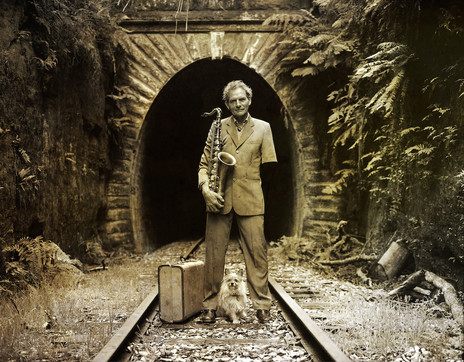

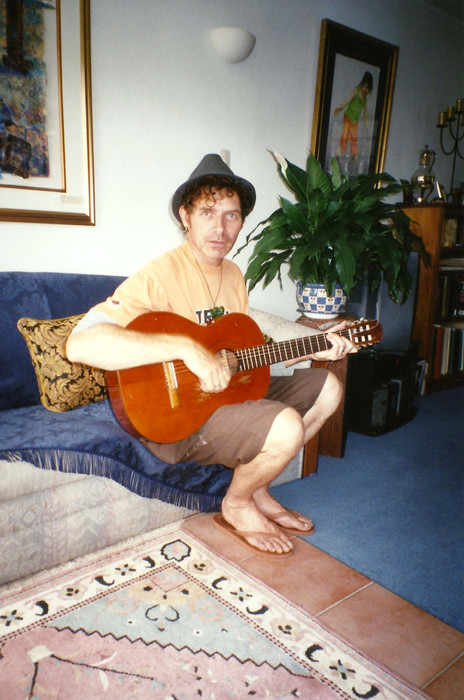

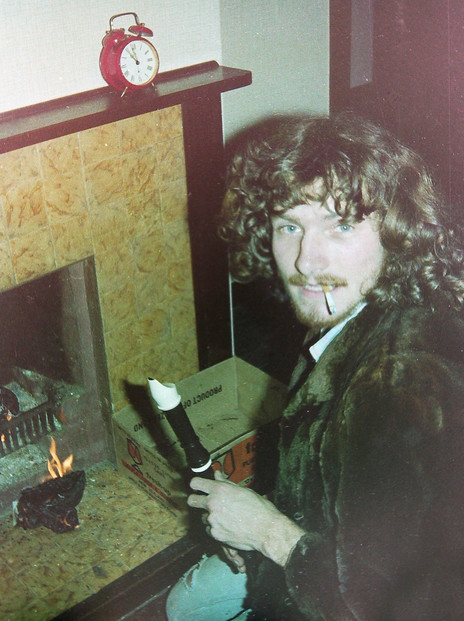

Neill Duncan was born in Timaru on 9 March 1957, although he grew up in Brighton, Christchurch. His family eventually settled on Auckland’s North Shore, where Neill’s dad took him to see old-time Dixieland jazz gigs, kickstarting a deep lifetime love of New Orleans jazz. Despite graduating as a teacher, music quickly won as an abiding passion, and in addition to becoming an adept saxophone exponent, he discovered quite by accident that he had a talent for drumming. As musician/ luthier Harmen Hielkema tells it, he accidentally split a drum skin one night and went home to get a new one. Curious, Neill turned the drum over and played on the other side. It was a eureka moment.

Neill, wrote Hielkema on his blog, could not only “play the saxophones brilliantly, but was a whiz on percussion, a rare combination. And I don’t mean just what are called ‘toy’ percussion instruments (handheld) but a full percussion kit. Neill added a whole new dimension.” Years later, Neill would perform with Hielkema in The Jews Brothers.

With Anthony Donaldson, he would form the most innovative ensemble of his career, Primitive Art Group

Abandoning his nascent teaching career after his qualifying year in Gisborne, Neill headed for Wellington, where he attended a jazz workshop in 1980, meeting percussionist Anthony Donaldson, with whom he would soon form the most outwardly innovative ensemble of his career, Primitive Art Group. The two musicians soldered their friendship with a listening session where Neill played Albert Ayler records to Anthony, who responded by playing Sonny Rollins records to Neill.

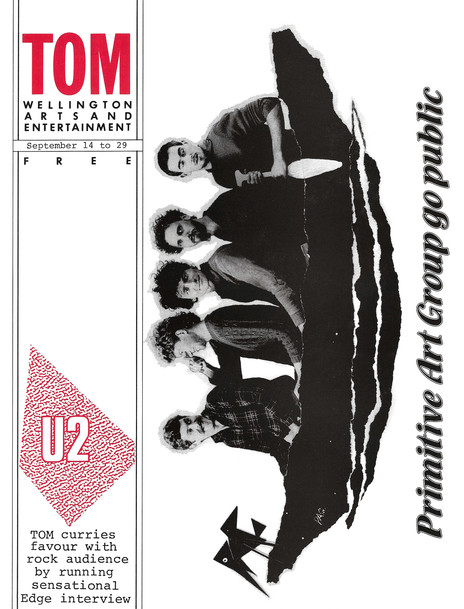

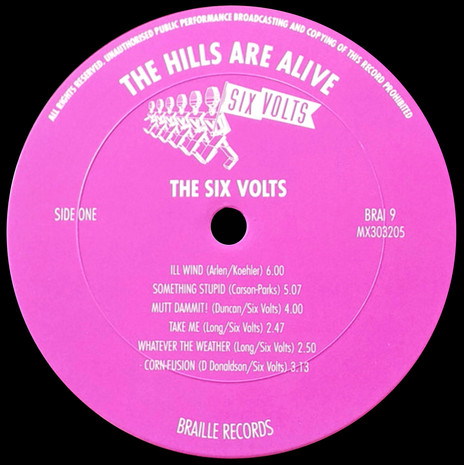

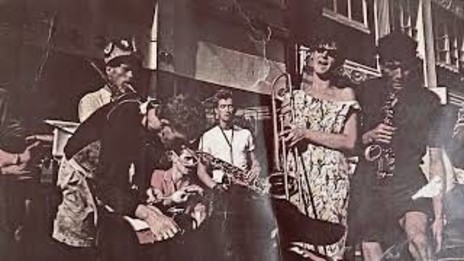

Primitive Art Group was active in Wellington between 1981 and 1986, in that time performing hundreds of gigs locally and around the country, and releasing two albums, Five Tread Drop Down (1984) and Future Jaw Clamp (1985) on their own label, Braille Records. Comprising of brothers Anthony and David Donaldson (drums and bass, respectively), David Watson (guitar), Stuart Porter (saxophone), and Neill (saxophone, percussion), PAG was a phenomenon to experience live and in a sympathetic environment, where it always felt like anything could happen.

Wellington in the early 1980s felt oppressive and somewhat monochrome with a flagging economy, the repressive Muldoon government and the Springbok rugby tour of 1981 dividing the nation. But even though their music was like a splash of bright colour through a scene dominated by post punks soaking in a Joy Division vibe, Primitive Art Group was respected by the underground rock tribe.

Although their music was undeniably in the free jazz tradition established by artists such as John Coltrane, Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman, they were white boys from a colony at the bottom of the world, so the sounds came out different. And in amongst the organic squall of acoustic improvisation there were unmistakable anchors: friendly whisps of melodic invention, moments of almost chamber jazz calm. While Watson’s guitar scribblings and Porter’s pealing sax represented the harder edges of free jazz, deep down there was something funky about the rhythm section, and in particular an access point in Neill’s playing, a lightness of touch and a willingness to entertain.

“As a player he really wore his heart on his sleeve, and had a very warm tone,” says former Primitive Art Group guitarist David Watson. “Within the PAG, his talent for mimicking phrasing and natural talent made some kind of tension with the avant-garde wings of the group. When it worked, and it mostly did, that tension was really useful.”

the public responded to the Primitive Arts Group performances with “sheer terror”

Watson recalls the sheer audience terror when the Wellington public experienced PAG perform in the glaring sunshine as part of the Wellington City Council Summer City programme: “The immediate rush of hundreds of families grabbing their picnic accoutrements by the armload and stampede-dashing for the exit should have been filmed for an early Peter Jackson horror. Not that we were much bothered. We played with our eyes closed.”

But he also recalls a very different gig where Neill ended up saving the day. The group, accustomed to playing to tiny crowds in tiny venues, performed at a large outdoor festival in Punakaiki. “As we started our set, graunching and grinding our jazz-skronk, some disgruntled folk had found they could purchase apples very cheaply and then entertain themselves in a DIY Kiwi fashion by throwing them at us. That was considered funny. A line of patched gang members coalesced around the front, all thumping the stage with meaty arms in unison, as if trying to get some obvious rhythm out of us. Apples were smashing into the stage around us. We fought back with our music and were right on the verge of a trainwreck in front of the vast crowd. But in this ruckus, Neill on soprano sax becomes the ‘centre that can hold’, leading us out of our melee, employing elegance, melody, energy and rhythm. It’s almost miraculous.”

Neill had this to say about Primitive Art Group and his perspective on what they were about:

“When the music swings, when it moves kinetically, I can relate to it, I can hook onto it. We used to say, the music has to roll like an egg, not a golf ball. And that was what Stuart and Anthony were doing the first time I heard them. They were going fucking ape shit but they were swinging. I couldn’t hear it then, I could only hear this massive sheet of sound and incredible noise and I loved it. I loved it because it was unadulterated expression. It wasn’t until Primitive Art Group got going that I had the epiphany of you can have five people screaming at the top of their heads and it can swing or it can’t swing. Anthony has this ability to play something really free but you can still hear the swing in it. And maybe it’s the notes he’s not playing. Maybe it’s what he’s implying. Maybe it’s just what he’s thinking. Who knows, but it’s swinging.

“We used to say, the music has to roll like an egg, not a golf ball”

“Primitive Art Group was the only time in my life I’ve ever played real music from the source, from a very emotional place. It was a very emotionally charged music. And interestingly enough, when you listen to Archie Shepp, he had something majorly to express, black politics. He politicised it and expressed that in his music. As five white boys in Wellington, we were emotionally charged as well, there was a fair bit of anger around, and that came out in our music. We didn’t purposefully say hey, stand up for this or stand up for that, but it definitely came out with some fucking angry nights and some angry gigs.”

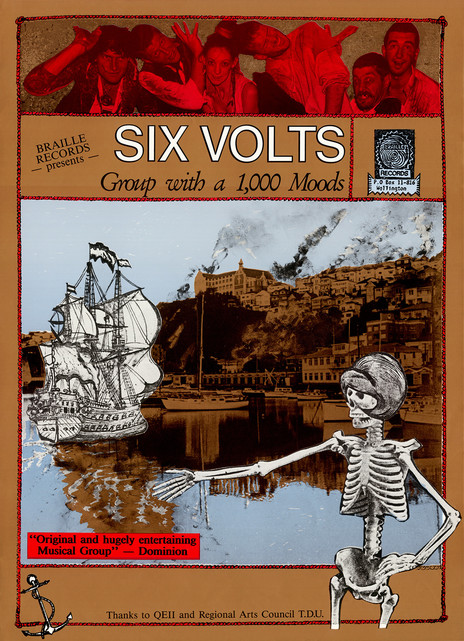

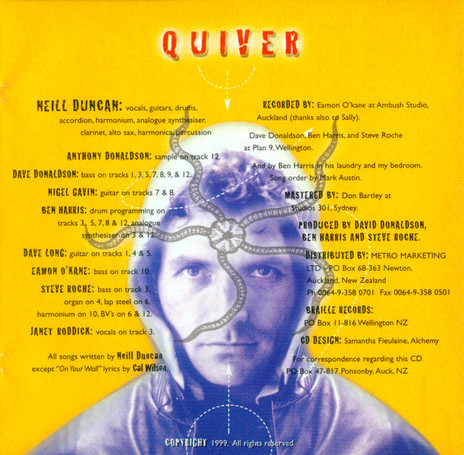

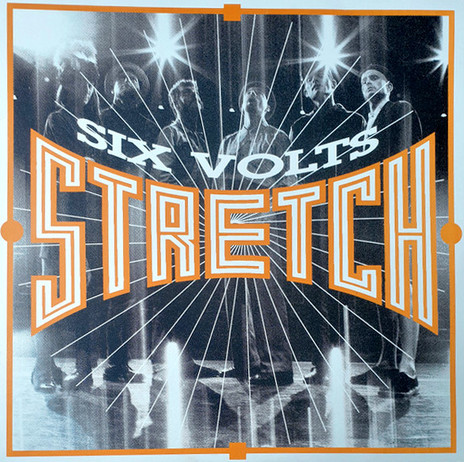

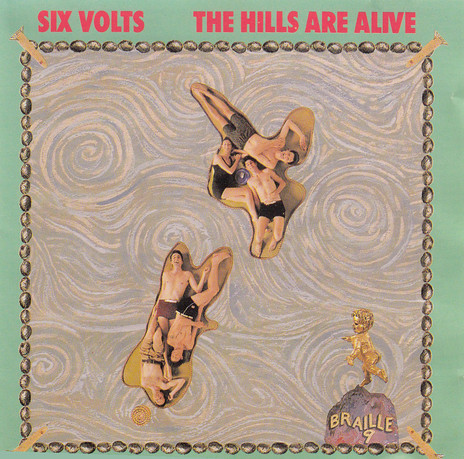

Primitive Art Group grew into a collective under the moniker of Braille Records, a musical repertory company with various more – and less – successful offshoots, some of them featuring Neill in their ranks. These included Four Volts and then Six Volts and the Bung Notes. Six Volts, who became something of an alt-jazz sensation, featured Neill on a variety of instruments including alto, soprano and tenor saxophones, clarinet and vocals, and included PAG members Anthony and David Donaldson alongside newcomers David Long (later to become a key member of The Mutton Birds) on guitar and opera-trained singer Janet Roddick. Six Volts were song-based and often performed mutant interpretations of songs as diverse as ‘Something Stupid’, ‘Black Dog’ and ‘Surabaya Johnny’. The group would also end up providing the background instrumentation for Songs From The Front Lawn, the first album by Don McGlashan and Harry Sinclair’s unique theatrical exposition.

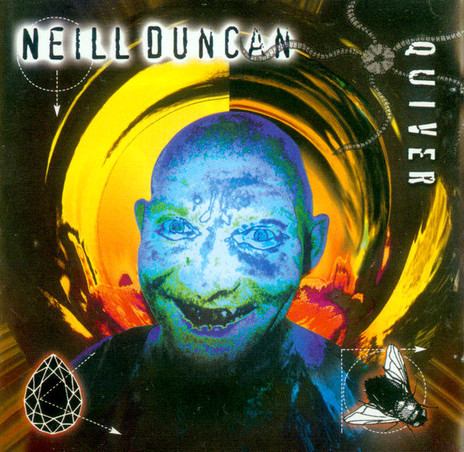

Neill’s other contributions to Braille Records include the one-off Jungle Suite project, A Walk Of Snipe (1986), which features his Six Volts pals David Long and Janet Roddick, and his only solo album, Quiver (1999), an album of intensely personal songs with a surprising, almost Chris Knox feel to it. There were also theatre shows like Threepenny Opera, Aunt Daisy, Cabaret and Flare Up – A Floral Explosion.

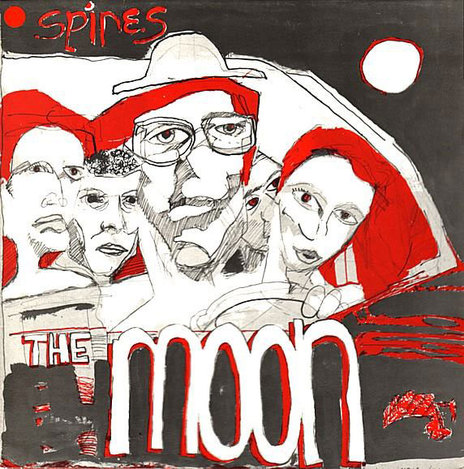

But PAG, Six Volts and Braille Records weren’t the sum total of his prodigious output in the 1980s; Neill was also a member of Jon McLeary’s critically acclaimed group Spines. While that outfit’s songs were clearly authored in McLeary’s distinctive style, the band’s music shifted from a fairly gloomy post-punk, almost ska feel to the unusual, rock with jazz elements of their one Flying Nun album, Idiot Sun (1986).

In fact, McLeary was one of the first contacts Neill made when he arrived in Wellington; he played flute with his pre-Spines group Negative Theatre, coming and going in Spines but maintaining an important friendship.

“He loved my songs and was in and out of every line-up of Spines until the mid ‘90s,” says McLeary. “He was my partner in crime with his humour, musicality and drive to experiment.” Musician/composer/producer Mark Austin says of Neill’s time with Spines: “If Jon dared to say ‘we don’t need sax in this tune mate,’ Neill would respond, ‘Cool, I’ll just play cowbell’ and the audience would be treated to an equally spectacular and educational cowbell solo that would again explore the limits of the instrument. Neill was engagingly enthusiastic and there was no holding him back!”

“Neill was engagingly enthusiastic and there was no holding him back!” – Mark austin

Austin would end up working on a number of Auckland-based projects with Neill in the 90s.

“I formed a soundtrack company with David Long in Auckland in 1991. When David and I teamed up with Don McGlashan on a feature film in 1992, we flew Neill up to play sax and clarinet solos. Later that year, Neill proposed he and I team up as musical directors of Cabaret at the Watershed Theatre. It was a fun band – we did abstract readings of the score and it was a very successful show – the first of many for Neill and me. Neill and I collaborated on a number of soundtracks for theatre shows (including Simon Bennett’s Titus Andronicus, Michael Hurst’s Hamlet, and Inside Out’s A Spectacle Of One) and we worked together on many individual projects before combining to write, direct and perform the music for Braindead The Musical (aided by Jeremy Jones, Russell Scones and the whole cast) in 1995 – a huge undertaking and a critical success.”

Based in Auckland throughout the 90s and living with his then-partner, comedian/actor Cal Wilson (RIP), in addition to his work with Austin he got stuck into a multiplicity of activities there, including tenures with The Blue Bottom Stompers and The Jews Brothers. It was on a Jews Brothers trip to Sydney in 2000 that he met Rachel Besser, and in 2002 they got married, living first in Bondi and then in Katoomba in the Blue Mountains. Although he continued to perform during the early part of the 2000s, his focus was on family life and raising his four children. Even so, he found time to establish new musical relationships and worked with bands like Darth Vegas, The Snaketown Rattlers and with guitarist John Stuart.

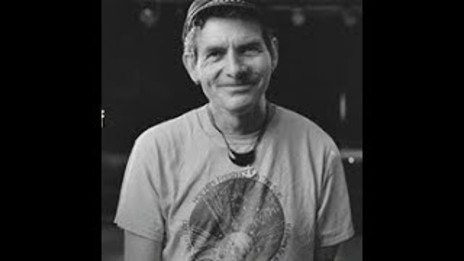

Then, in 2012, Neill was diagnosed with sarcoma. “I’m a musician. I support my family with one tool: my saxophone. So discovering I had cancer in my arm – and then having it chopped off – was a very dark time,” he said. After two rounds of chemotherapy, he had his arm amputated the week before Christmas 2012.

Neill’s positive attitude shines through on an online video of the jam session party the night before the amputation. “It’s incredibly gutsy,” says former PAG bandmate David Watson. “He’s just enjoying playing.”

In an article he wrote about his life-changing experience, Neill reveals that his fellow Darth Vegas bandmate Michael Lira tracked down Maarten Visser, an Amsterdam-based instrument maker who adapts wind instruments for people with disabilities. Subsequently, he custom-built the world’s only one-hand tenor sax, hydraulically moving the top keys to the bottom so that Neill could use just his right hand.

Neill’s second wife Naomi Parry – who he met in 2016 – says that he was “producing and teaching a lot in the post-amputation period and playing with John Stuart in the Three-Handed Beat Bandits. He played a lot of disability gigs and did some big keynotes and parliamentary addresses for Support Act. He also toured New Zealand with the Jews Brothers.

“We travelled to Birmingham in 2018 so he could address the One-Handed Musical Instrument Trust conference and then took the horn back to Maarten Visser at Flutelab in Amsterdam so he could repair it and make it stronger. After that he really got back into his music and began planning to record songs he’d written with John. We got through the [New South Wales] fires and managed to make it to Wellington to record in February and March 2020, getting home just before Covid. The Devil’s Gate formed out of those recording sessions and songs and that’s the recording that became Phantom Tones.”

That album, released posthumously in January 2023, features songs developed by Neill and John Stuart and performed with collaborators old and new, including Anthony and David Donaldson, Steve Roche and Daniel Beban.

“Neill started getting sick in May 2021 and was first hospitalised on 21 June,” says Naomi. “From July he was undergoing rigorous chemotherapy for a rare form of diffuse large b-cell lymphoma. It was a new cancer but it’s possible the chemo for the first cancer created the new one, nine years down the track. For a while he made a good recovery, all through Covid lockdowns, but he began experiencing pain again in November. In early December we found out it had roared back and decided we’d better get married. We married in the garden of Varuna, the National Writers House on Christmas Eve 2021.

“He was preparing for a new round of chemo then, and had received a grant to record his songs with Lloyd Swanton (of The Necks), James Greening, and Alon Ilsar, but he just didn’t have the strength. Lloyd came over though just before Christmas and they played together and he knew how it would sound and he was content. He also felt he finally understood Ornette Coleman’s theory of harmolodics and that he’d achieved the sounds he was working towards all his life.

“His heart suddenly stopped on the morning of 28 December, 2021 at our home here in Katoomba. It was a shock to us all.”

Notes David Donaldson: “In retrospect I kind of took Neill for granted, as he was such a constant companion through a defining part of my musical career, as well as a great friend. He was a larger than life character and one of the most natural musicians I’ve ever met. Lately, I’ve been digitising hours and hours of live gigs of the Four and Six Volts as well as the Bung Notes. I’m kind of in awe of his playing. He really was an amazing player and performer. Like all of us in the Volts, we excelled in a live setting. In 1990 for example, the Six Volts played 90 gigs as part of three national tours. We were incredibly playing fit and it’s a shame we didn’t record a live album because that’s where Neill really came to life. He was a born performer.”

“when your horizons are broadened by music so is your whole outlook on everything”

Gregarious, with a friend in every port and living and breathing music, Neill Duncan’s loss is palpable. A dashing, always well-dressed chap with a wide-eyed, almost naïve enthusiasm, Neill was a welcome contrast to the many musicians who become bitter and tired as the years sap their spark. And of course, that makes his premature death even more tragic. Happily, however, his music lives on in the Devils Gate Outfit, which takes its cues from Neill and continues to perform his compositions. It’s hardly compensation for a life, but it looks certain that his legacy won’t be forgotten, with Devils Gate Outfit member Daniel Beban’s tome on Primitive Art Group and its various spin-offs (Future Jaw-Clap out through Te Herenga Waka University Press), and a double album of Primitive Art Group live recordings, 1981-1986 also due imminently.

But let’s end with a quote from Neill that sums up his open-hearted attitude:

“I still remember the first time I actually saw my horizons open, an epiphany. It was when Anthony played me Out To Lunch, Eric Dolphy. Even though it’s not an overly free record, [it’s] the level of improvisation and the level of connection between the players and the freedom and the movements and the flows. It’s magnificent. You have a beautiful composition and then it blossoms out into this completely free improvisation but it’s all related to the melody you’ve just heard. That’s when I really just went ‘wow, okay.’ All of a sudden my views on music and life broadened. Music’s my life, so when your horizons are broadened by music so is your whole outlook on everything, arts, music, people, love, all those things, it just opens everything up.”