Her childhood in Taumarunui was busy and convivial with music integral in whānau life. Close harmonies reigned and performance was collective – at home, the local marae and other family gatherings – with Mahinaarangi’s eclectic guitar playing and improvisational bent already apparent.

While formal education was valued – both parents met at Wellington Teachers College and her father taught at Taumarunui High School – Mahinaarangi’s early musical influences were more organic, absorbed through a high rotation of traditional waiata, Catholic hymns and her jazz-fan father’s Ella Fitzgerald, Mills Brothers and Southernaires albums.

However, Mahinaarangi’s sporting prowess as a competitive diver and keen netballer was more to the fore during school years, and she was by her own description “an absolutely staunch kapa haka chick”. On leaving school, music wasn’t an initial career choice either. She entered the nursing school then attached to the Taumarunui Hospital.

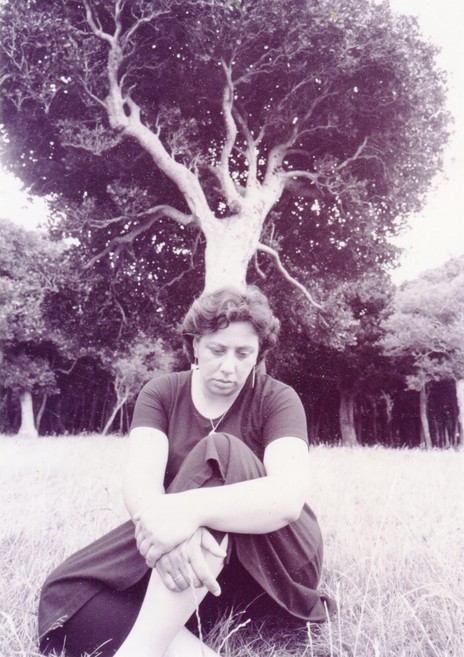

But Mahinaarangi had been compiling a collection of her own songs and poetry on a more private scale for years. One writer described her using music “as a survival kit, from her first day of school when she wrote a song on the way to help her cope”.

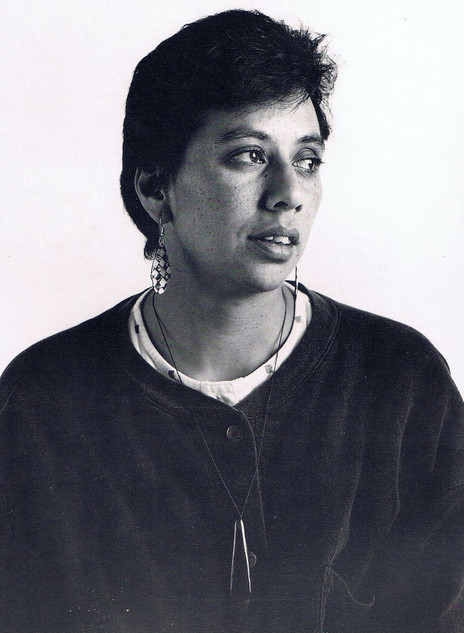

Travels overseas in the late 1970s prompted a refocus to seriously consider performing her own music, and ultimately settling in central Auckland, she connected with an inner-city milieu of independent musicians at a fertile and politically active time. Venues such as Java Jive and Atomic Café provided well networked outlets and audiences for the “shy but firm” singer-songwriter, as well as the occasional dishwashing stint between gigs. And she started recording and building her extensive repertoire.

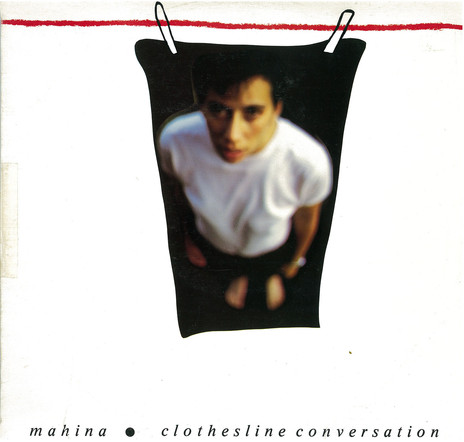

HER beguiling vocals and emotive but intelligent songs introduced a talented artist.

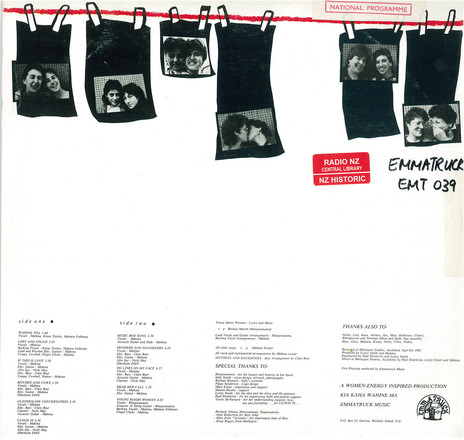

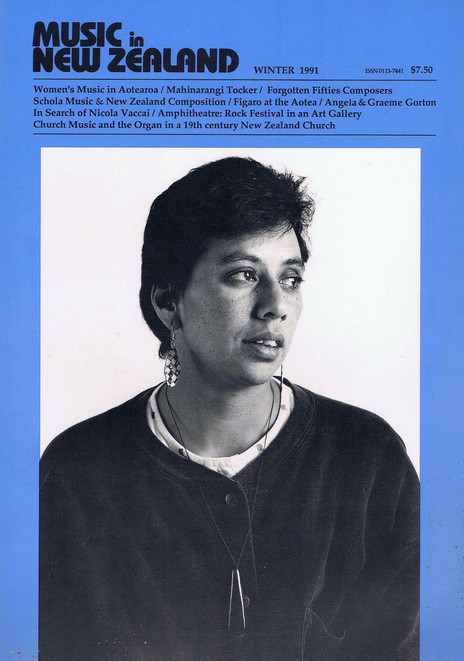

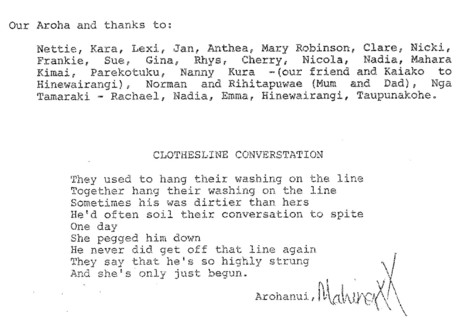

With the release of three of her tracks on the Web Women’s Collective compilation album Out of the Corners and her first full length album Clothesline Conversation in 1982, Mahinaarangi’s beguiling vocals and emotive but intelligent songs quickly made her name as a talented artist who wrote beautiful melodies and intuitive jazz flavoured folk-pop songs, but was not afraid to write about provocative or controversial issues. She had seated her first releases firmly in the feminist “Women’s Music” camp alongside The Topp Twins, Hilary King, Jess Hawk Oakenstar and fellow activist Māori female musicians, Mereana Pitman and Tracy Huirama.

Right at the close of a very busy 1982, she gave birth to her daughter, Hinewairangi, and the strands of intergenerational whānau connections and plural heritage echoed back and forth even more throughout her lyrics. While both her parents spoke te reo fluently, Mahinaarangi grew up when the language was completely absent from the classroom. As a Māori songwriter who wrote the majority of her lyrics in English, she was unabashed about using words, phrases, and on occasion complete songs in Māori, always encouragingly and carefully edited by her mother throughout her career.

In 1985, she had further tracks released on Auckland Acoustics, another compilation on the Real Groovy label masterminded by “culture creator” Chris Priestley with several locally based independent songwriters active in the burgeoning acoustic-cum-folk scene. Her second album, I’m Going Home, released in 1987, led to an extensive international touring foray to the Bruges Festival in Belgium with Marion Arts and Robbie Laven (Red Hot Peppers), the Vancouver Folk Festival and the Michigan Womyn’s Festival. She was the first Māori woman to appear at all three events.

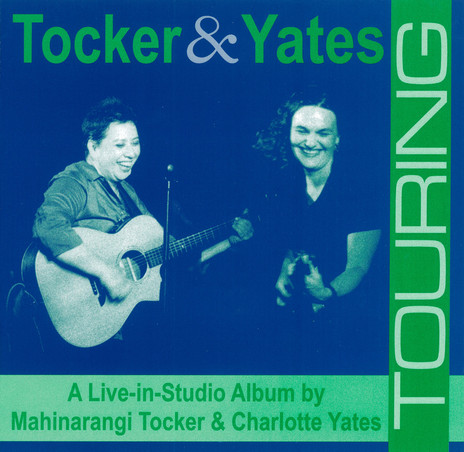

She maintained lifelong connections with the local folk music circuit from Whare Flat to the Auckland Folk Festival, enjoying the jamming camaraderie and open mic “DIY” ethos, as well as the deep community and cultural links. However, the international folk festivals provided a portal into meeting the myriad of styles and ways of creating music that soon received the epithet “world music”. She was fascinated with new sounds and loved meeting musicians from all parts of the globe. Her openness, legendary good humour and generosity made for quick introductions and she loved to offer her talent and see how she could incorporate new influences, respectfully, in her own work. It was no surprise Mahinaarangi was a featured soloist at New Zealand’s inaugural Womad festival in 1997.

Her openness, legendary good humour and generosity made for quick introductions.

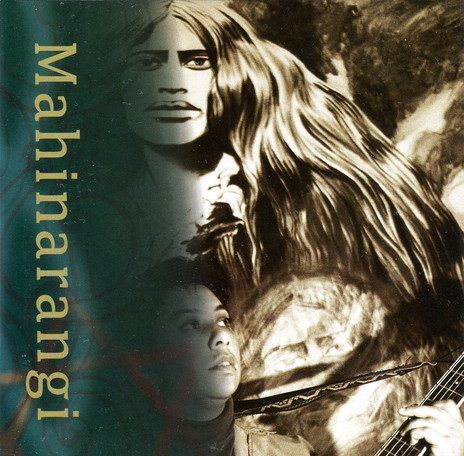

As a songwriter she was keen to see other artists perform and record her songs. In 1992, Annie Crummer’s debut top 10 album, Language, included Mahinaarangi’s song, ‘Make Up’. This assisted Mahinaarangi to be able to release her third album, Mahinarangi, a 10-year retrospective, on a major label for the first time in 1996.

Sony/Tristar/Columbia released her fourth album Te Ripo in 1997, produced by Shona Laing. The relationship with the label did not continue and her ambivalence with the industry part of the music business is well documented.

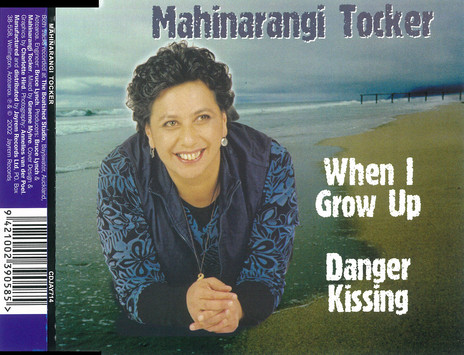

Other elements of a public persona presented challenges for Mahinaarangi. Struggles with self-esteem and self-confidence seemed at odds with someone who once turned up at my dressing room door wearing nothing but a Christmas decoration, or who had no issue singing for the opening of Parliament invited by the then Prime Minister elect, Helen Clark. Managing her mental health more successfully led to her taking part in the television campaign Like Minds Like Mine to destigmatise mental illness, with her song ‘When I Grow Up’ as the soundtrack in 2001. It also led to her training as a facilitator for Korowai Whaiora workshops about human rights issues for and by those who have experienced mental illness.

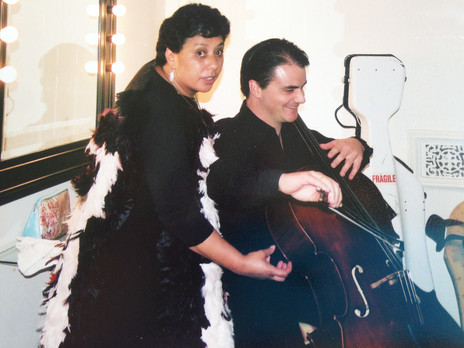

From 1999, Mahinaarangi was interacting significantly with musicians and composers from the classical community, meeting other key collaborators and working on a dizzying array of projects. She met composer David Downes during Michael Parmenter’s epic dance/voice work, Jerusalem, and co-wrote and recorded ‘Never No More’ with him for the Baxter compilation album and arts festival concert series in 2000-2002. Downes composed the soundtrack (songs) for Michael Heath’s film A Small Life, for which Mahinaarangi wrote lyrics. She also played the leading role, winning best actress at the 2002 Karachi Film Festival. One of the songs, ‘I’ll Breathe for You’, was included on Hei Ha!, her fifth album of original work, released by Jayrem Records and co-produced by Mahinaarangi and the renowned Bruce Lynch.

In 2001, Mahinaarangi was invited to be part of a nine-piece Māori chorale led by Dilworth Karaka (Herbs) to provide backing vocals for Dame Kiri Te Kanawa on her best-selling album of traditional and contemporary waiata, Māori Songs. Released on EMI, this sold over 60,000 copies.

Mahinaarangi was also named by public vote 2001 Queer Musician of the Year and we performed to sellout shows at the 2002 Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. She was proud to perform gratis for Auckland’s Big Gay Out and frequently supported gay pride events.

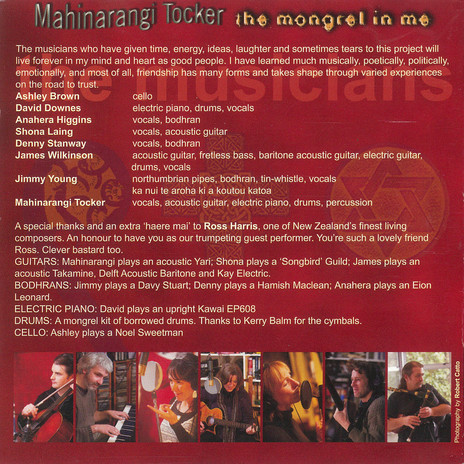

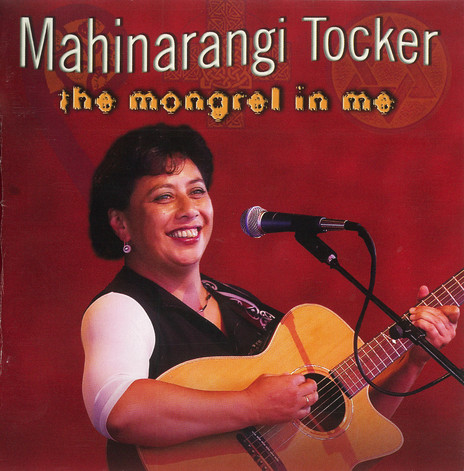

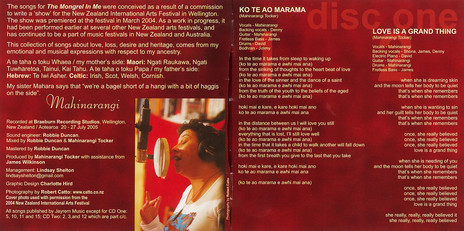

David Downes, Shona Laing, cellist Ashley Brown, vocalist Anahera Higgins – together with folk darlings Denny Stanway, Jimmy Young, James Wilkinson and composer/trumpeter Ross Harris – began a mighty performance and 22-track double-disc recording collaboration as the Mongrels, for Mahinaarangi’s final opus, The Mongrel In Me, commissioned for the 2004 New Zealand Festival. Ross Harris also invited Mahinaarangi to write the libretto for his opera, Roimata, and perform with the Auckland Philharmonia.

She worked again with Ashley Brown and his colleagues from NZ Trio on her setting of Hone Tuwhare’s poem, ‘A Northland Heartscape’, recording and performing for both the NZ Festival and the Auckland Arts Festival (2005-2007). Both poetry compilations (Baxter and Tuwhare) were top 40 releases. Meanwhile, her song ‘Winter’ was also released on the 2004 Strawpeople album Count Backwards from Ten.

In September 2007 – with her mother, Rihutapuwae Tocker – she was a finalist for the APRA Maioha award (excellence in contemporary Māori music) for best waiata for their song, ‘Taku Kōtiro’. In the 2008 New Year’s honours list, Mahinaarangi became a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit, for services to music.

On 29 March 2008, she performed solo at the opening afternoon concert of the Titirangi Festival of Music. This was her final show. I am profoundly and ever grateful that I had the chance to speak with her one last time, late evening 30 March. On the morning of 8 April 2008, I received a phone call that Mahinaarangi was in North Shore Hospital in a coma, after a massive asthma attack. She died peacefully on 15 April 2008, surrounded by her whānau.

--

Read more: Jess Hawk Oakenstar interviews Mahinaarangi Tocker, 1985.