“I doubt angels could match him,” remarked one commentator.

He has become the voice to call on when the country needs soothing and uniting. When Canterbury fell in the 2011 earthquake, he and his band The Unfaithful Ways emerged from the rubble to deliver warm country harmonies on the back of a horse float or in abandoned parking lots.

When New Zealand was shocked with the devastating Mosque massacre in 2019, he had a waiata ready for the remembrance service. “I doubt angels could match him,” remarked one commentator. When the world was locked down during Covid-19, Marlon was there on our screens, singing songs in front of a roaring fire, his voice as gorgeous as ever despite a spluttering internet connection.

There’s perhaps no other musician currently working in New Zealand beloved by such a wide audience: millennials and boomers, Māori and Pākehā, religious and atheist, queer and hetero. The “Prince of Lyttelton”, as some locals dubbed him, has endeared himself to the whole nation in the last decade.

Early life

Some would say he had an auspicious start: born on a full moon, on New Year’s Eve 1990 in a bathtub, and named after an iconic movie star. Marlon was surrounded by music from the beginning. There were Chopin or Beethoven piano sonatas lulling him to sleep; his dad blared loud punk classics; his kuia, with her Billie Holiday-esque voice, sang him Bob Dylan songs, and his artist mum insisted he memorise all the words and tunes to Kāi Tahu waiata before they went to the annual hui.

He soaked it all in. The Band’s Music from Big Pink was an early obsession for Marlon. But his dad had a habit of trading in CDs almost every week, and when that one disappeared it was replaced by Gram Parsons’ Grievous Angel, an album that had a profound effect on his sound later on.

With Kāi Tahu on his mum Jenny Rendall’s side, and Ngāi Tai on his dad David Williams’ side, Marlon learned to use his vocal cords loud and clear on the marae.

His parents separated when he was five, and Marlon had a free range, bohemian childhood that he says actually made him a little anxious. The primary school choir, with its hard rules and clearly delineated roles, was a haven. “Music was the first recognition of strict lines in which to work,” he told the Sydney Morning Herald, “because if you sing, like, and it’s a little bit sharp, it doesn’t make sense. It was a really nice, really human moment for me.”

Around the same time, he began to take classical guitar lessons, learning to play Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, but Marlon really just needed a few chords to accompany the songs he loved to sing.

His mother says he was at home on stage from very early on. He won the Lyttelton Primary School talent quest at 11, singing a gospel number. “The whole audience was spellbound, including me,” Rendall told Stuff.

A couple of years later, in his first year at Christchurch Boys High, he found himself lined up in the assembly hall, learning the school song. He caught the attention of choirmaster Don Whelan immediately.

Marlon says of Whelan, “... [he] would walk around with his ear out, listening to everybody with a handful of coins rattling around, and then just start throwing coins at the kids who were singing the best. And I remember I got a two-dollar coin, and I started to get the stupid notion that music might be kind of lucrative.”

Choral singing, both at Boys’ High and for the Christchurch Cathedral Choir, was an intensive training ground for Marlon, who would spend up to 16 hours a week singing requiems, canticles, and psalms.

“He has a beautiful, golden, mellow voice that never needs to be pushed,” Whelan told the Sydney Morning Herald. “He also had that special knack of charisma. I would call it the Elvis factor because there’s a long amount of flopped hair. I wouldn’t say there was necessarily a pelvic thrust, but there was certainly a connection between the young Elvis and the young Marlon.”

Teens / Unfaithful Ways

Fifteen-year-old Williams started writing songs with his best friend, Ben Woolley. Their first band was called Woolley Fish.

“We met at a choir rehearsal in our first year of high school,” Woolley told Vicki Anderson of Stuff. “And if I remember rightly, we were singing a Billy Joel song of which we share a mutual distaste. Despite this relatively horrific setting, and perhaps partly because of it, we managed to form a friendship; a friendship based upon a shared hatred for Billy Joel’s music, and that we don’t now, and never did, lie to each other.”

Their pitch-perfect voices blended like brothers. They began leading a double life, by day as choirboys, by night, as swaggering guitar-toting country boys, enamoured with the songwriting of Gram Parsons and Townes Van Zandt. By 17 he and Ben had joined with fellow Christchurch Boys’ High student Sebastian Warne, who took guitar duties and rounded out the vocals, and they eventually recruited their science teacher, Simon Brouwer on drums. They went by the name The Unfaithful Ways.

Their pitch-perfect voices blended like brothers.

They took out the Best Song award at the Rockquest competition in 2008, and in 2009 recorded a four-track EP and toured around the country.

The end of the same year saw Marlon and Ben touring Europe with the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament Choir, singing in churches in the Baltic states, Spain, Portugal and San Francisco. Marlon toyed with the idea of taking his training seriously, with the aim of becoming an opera singer. He spent a year studying with Dame Malvina Major, taking classes with Max Cryer, and learning Russian. But classical music couldn’t keep him. The pull of the party scene, and of country music, was too magnetic.

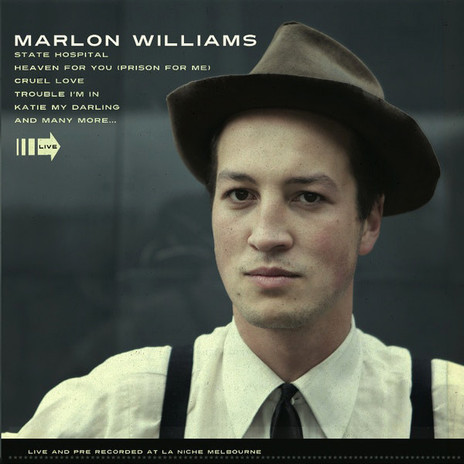

The Unfaithful Ways played regularly around Canterbury and quickly gained national attention. Their EP, released in August 2009, comprised a lovelorn set of four songs accompanied by twanging mandolin, at an ambling, equine pace. They looked the part too, with cowboy boots, long silk bows at their necks and Stetson hats on their heads. Marlon’s style was especially remarked upon by the media, with journalist Vicki Anderson observing that he had the “face of a choirboy and the shoes of an Italian film star”.

Around 2010 it seemed like the close-knit port town of Lyttelton had more bars than anywhere else in the country. Many were venues for music and a little chaotic at times, with artistic locals rubbing shoulders with international sailors in the port, all of them up for pints aplenty.

And it was quickly gaining a reputation for turning out old-timey, folk-country music. Roaring roots duo The Eastern had been doing the hard yards travelling around Aotearoa for a couple of years, and had released a trio of EPs in a short time. Country-noir musician Delaney Davidson had started to return to New Zealand for an annual tour, after years in Europe with The Dead Brothers. His New Zealand base was at Governors Bay, just around the shoreline from Lyttelton. Other musicians, like Aldous Harding, Nadia Reid, and Anita Clarke (Motte, Ragamuffin Children) were later drawn to Lyttelton.

Producer Ben Edwards recorded them all. He started his studio The Sitting Room in Christchurch city, where he first met The Unfaithful Ways practising in one of the studio’s spaces. “I remember thinking after a few rehearsals ‘they’re pretty good – they’re not amazing, but they’re pretty good.’”

Edwards agreed to record their debut LP, and started work on it mid-2010. They were nearly finished when an earthquake in September of that year made the studio unstable. They set up again in another building for the mixing early in 2011. When the catastrophic Canterbury earthquake of February 22 happened, The Sitting Room was marked for demolition. A couple of structural engineers made a rescue mission and saved the master recordings for The Unfaithful Ways’ debut LP.

In late October the album Free Rein landed on shelves, showcasing vocals in the band, weaving close harmonies, fiddle and pedal steel, and some world-weary, cynical lyrics well beyond their years. “The Unfaithful Ways essentially tackle a full spectrum exploration of the human condition, all irrationalities and warts left in the mix,” wrote reviewer Martyn Pepperell.

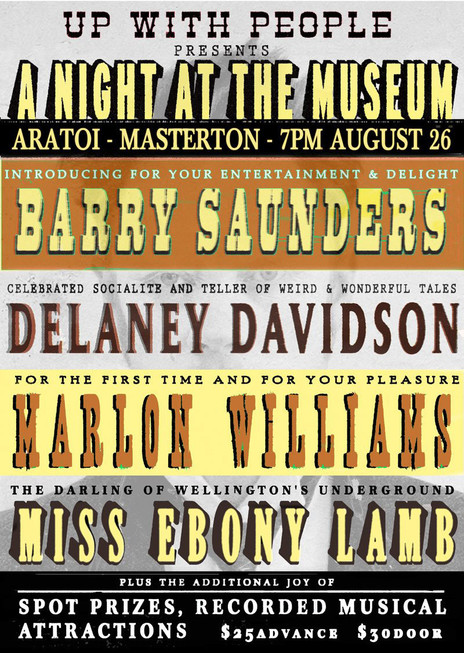

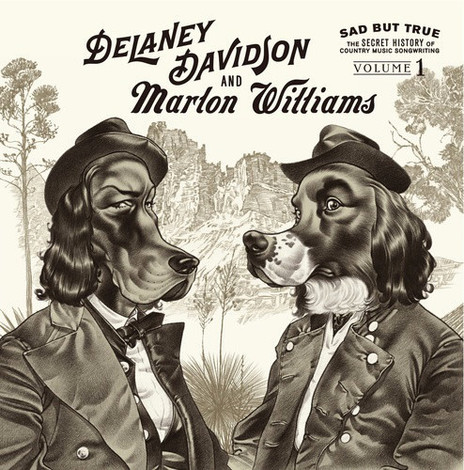

Delaney/Earthquake

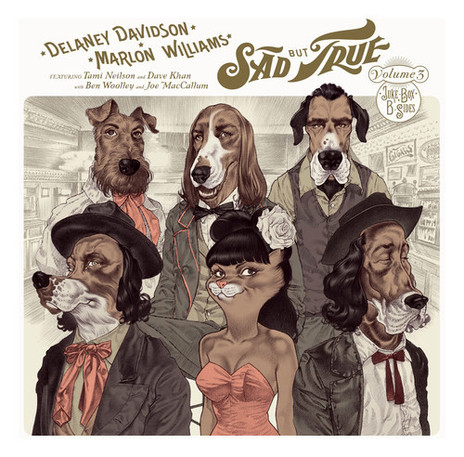

On the day of that earthquake, Marlon was sitting with Delaney Davidson outside the Lyttelton Coffee Company, planning their collaborative Sad But True, The Secret History of Country Music Songwriting albums. They’d met through matchmaker Adam McGrath (The Eastern) who had booked both to cover him for a gig at Wunderbar. They were thrilled to find so many songs they both knew and loved, and they harmonised naturally.

During the year that followed, in that city of rubble, the two wrote and recorded their first album together.

Marlon’s voice is smooth and youthful; Delaney’s is gravelly and menacing, and 18 years older.

“I had to make him sit in one place,” says Delaney of the co-writing process. “You just have to stay in the chair. If you stay there long enough you’ll have a song.” They developed a deep connection, and method that continues to this day. “One hacks out the rough shape and the other can refine and look for nuance.”

The pairing is as different as two voices could be. Marlon’s voice is smooth and youthful; Delaney’s is gravelly and menacing, and 18 years older. But they were both students of country music, as the title suggests, and these albums were a homage to all the different facets of the genre.

“For me, country music is about simplicity of form, it’s about sentimental honesty,” said Marlon in a documentary made in 2016.

The album took out the NZ Music Awards for best country album and song in 2013. The third volume of the series, in 2014, added the voice of Tami Neilson and fiddle of Dave Khan to the mix.

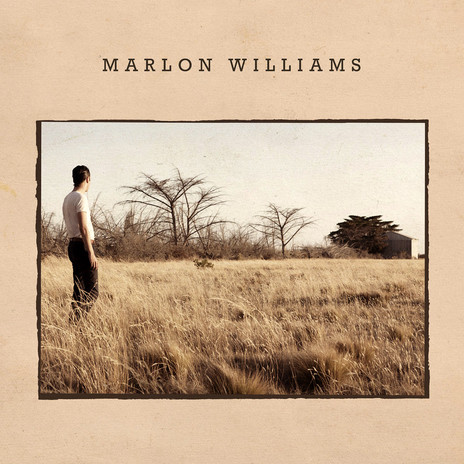

By this time, The Unfaithful Ways had petered out. Marlon had helped Ben Edwards record his friend Hannah (Aldous) Harding’s debut in the summer of 2012, and by mid 2013 he’d moved to Melbourne, and was living above iconic rock pub The Yarra Hotel, making a name for himself as a solo performer. When it came time to record his debut solo album, he returned home to work with Ben Edwards, who had set up his new studio just a few doors up the road from Marlon’s mum’s house in Lyttelton.

Solo

The self-titled album would prick up the ears of music media internationally, and showcased the range of characters, styles and voices Marlon was capable of.

“We actually had a different plan initially for his album,” Ben Edwards told Vicki Anderson. “The first half is the songs as you hear them now, the second side was going to be Marlon as you’ve never heard him before. There’s a bunch of songs here we did with Marlon just screaming over the top of Lyttelton noise band Asian Tang. But in the end, we decided it was probably a bit too far for a first release. People shouldn’t pigeonhole him as just an alt-country singer because he’s more than that.”

The album gallops out the gate with ‘Hello Miss Lonesome’ which he later performed with his band on Conan O’Brien’s TV show, compelling viewers to mid-song applause by holding a note that lasted a death-defying eight whole bars. It moves through the subdued ‘Dark Child’, a song penned by a friend of Marlon’s written from the point of view of a parent burying his child; a faithful cover of Terry Randazzo’s 1964 melodramatic symphonic pop song ‘I’m Lost Without You’. He also interprets a fingerpicked folk number from 1975 by Canadian songwriter Bob Carpenter, and the operatic folk of ‘When I Was A Young Girl’, a trad song recorded by Nina Simone, Odetta, and others. Marlon showed his ability to make these songs his own and deliver them with as much emotion as if he’d written them himself.

Being schooled in folk traditions meant he knew songwriting and performing didn’t have to be one and the same thing. And it was more comfortable for him to tell other people’s stories. Songwriting, and sharing his innermost feelings, wasn’t something that came easily for Marlon.

Marlon worked hard over the next three years, touring nearly non-stop.

“I mean, I find it ecstatic to finish a song,” he explains. “To have done one doesn’t feel like an accomplishment as much as a relief and maybe a curiosity, you know? To have come through to the other side and have something. But it certainly always feels messy.”

Marlon worked hard over the next three years, touring nearly non-stop around the US, Australia, Europe and the UK, and back home, sometimes just with his guitar, sometimes with his band The Yarra Benders. His childhood mate Ben Woolley backed him on bass and brought those brotherly harmonies, Dave Khan joined on fiddle and mandolin, and Yarra Hotel bartender Gus Agars was on drums.

In 2015 Marlon inked a deal with American indie label Dead Oceans, releasing the debut worldwide.

Maybe it wasn’t a great time to fall in love with another up-and-coming music star, but Aldous Harding and Marlon Williams took their longtime friendship and musical collaboration and made the plunge into a romantic relationship anyway. Aldous’s first album had made waves not only in New Zealand, but internationally too, and their busy tour schedules didn’t match up all that often.

When the relationship ended, Marlon retreated to Lyttelton, and used his broken heart to fuel a flurry of deeply personal songwriting.

“I hadn’t finished a song in two years,” he told Clash magazine. “And then in a matter of three and a half weeks I came out with 15 or so. It really felt like I came out the other end with blood on my hands, and I couldn’t remember anything that had happened.”

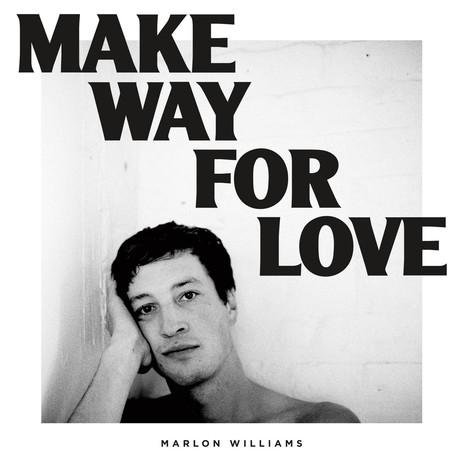

His resulting second album Make Way For Love funnelled complex, sometimes ugly emotions (jealousy, bitterness) into devastatingly gorgeous songs. American producer Noah Georgeson worked with the band for 12 days refining the songs and recording them.

While the album was written and recorded in a rush, the songwriting showed Marlon was learning new tricks. The pinnacle of the album was ‘Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore’. It’s an astonishing song in many ways, not least of which is the fact that Aldous Harding agreed to sing as Marlon’s duet partner, from a separate studio in Cardiff, Wales. The five-minute song starts out as a stoic mantra, but two-thirds of the way through there’s an E minor 7 chord change that signals the truth of the matter. “That’s the moment where I don’t believe my own hype and the game’s given up.”

“What am I gonna do / When you’re in trouble / and you don’t call out for me,” he sings.

‘Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore’ won the APRA Silver Scroll in 2018.

He told the Takenote podcast, “It’s the one that was the most edifying. It’s the one that I actually learned from, from writing, and feel … And I feel that giving expression to something that I can’t express using ordinary language … yeah, that’s the closest thing to success I’ve felt as a songwriter.”

The song won the prestigious songwriting award the APRA Silver Scroll in 2018, and at the NZ Music Awards the album won Marlon best solo artist and album of the year.

The 2019 live recording Live At The Auckland Town Hall shows Marlon as a commanding, polished performer, as he breezes through 21 songs backed by The Yarra Benders. He gives all of his energy to the audience, and his band clearly adore playing with him. By the time he gets to the encore, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ ‘Portrait Of A Man’ with its lyrics “I am using all the colors of blue/ I have here on my stand / I am painting in oil, a portrait and I’m the man” – everyone in that captivated audience seems to agree. He’s the man.

Marlon has flirted with film since 2015, scoring bit parts in a couple of indie films and TV series. Actor and director Bradley Cooper specifically requested Marlon to play a young-gun country music prodigy in the blockbuster A Star Is Born. He adeptly takes the vocals on Roy Orbison’s ‘Oh, Pretty Woman’ alongside Cooper and roots singer Brandi Carlile. He played Ned Kelly’s stepfather in the arthouse Australian film The True History of The Kelly Gang, and appears in Lone Wolf, another indie film released in late 2020, directed by Jonathan Ogilvie.

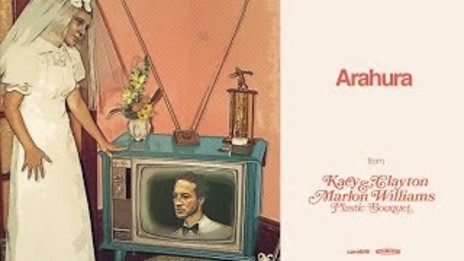

2020 also sees the release of Plastic Bouquet, a collaborative album which was recorded at Christmas 2018 in Saskatoon, Canada, with duo Kacy and Clayton.

“My last album was a very personal self-regarding, self-cannibalising album,” he told Kim Hill. “So for me, one of the most exciting things about working with Kacy and Clayton was exploring those forms again and using limited chords and really familiar tropes that everyone can grab onto easily.”

The pandemic of 2020 has meant that for the first time in a decade, he has stayed still, in Aotearoa, settling around the coast from Lyttelton in Diamond Harbour. He’s brushing up on his te reo Māori, with the aim of recording an album, co-writing and spending quality time with whānau.

In early 2021 he will do his first solo tour in six years, which he’s described as “a show of two worlds, Te Pō me Te Ao Mārama. Come and watch me flit between song-and-dance man with manic smile and bells on and Byronic, self-possessed cretin with no regard for anyone or anything but his own diseased thoughts.”

--

Updates:

Marlon Williams originally planned to only perform a handful of shows as a solo act within the Auckland region – at Leigh Sawmill, the Auckland Town Hall Concert Chamber, and the Hollywood Cinema – but these sold out quickly. More were added to meet demand, until his run extended to nine shows in all. Williams entertained the audiences by moving between differently decorated areas of the stage: from a makeshift lounge created in one corner where he played guitar; to a formally set up piano on the other side; to centre stage where a large screen behind him allowed him to sing ‘Vampire Again’ karaoke-style while dancing in front of projections as if he was recreating a video clip live.

He began to drop the odd phrase of te reo effortlessly into his music

In September of the following year, his New Zealand fanbase sent his new album My Boy (2022) straight to No.1. His growing confidence as a songwriter gave him the freedom to mix emotive tracks (‘Promises’) with more light-hearted ones such as the title track with its quirky “do-do do-do” chorus. The song also had a hint of 80s pop sound, which was echoed on ‘Thinking of Nina’. He also dropped the odd phrase of te reo effortlessly into his music, such as the moment in ‘Don’t Go Back’ where he mentions the call of the ruru – “Tērā te tangi a te ruru”.

His comfort with singing in te reo also saw him brought in to provide backing vocals for Lorde’s EP, Te Ao Mārama (which had five translated versions of songs from her 2021 Solar Power album). She then took him on tour as her support act through the UK and Europe, which included a final night duet of ‘Mata Kahore’ at the Alexandra Palace in London. Not long afterward, he took off for two more months of his own shows in the northern hemisphere. This led to a mention in the New Yorker, which proclaimed: “Elvis is really Williams’s best analogue. Both men manage, by turns, to be profane and sacred, wizened and innocent, seductive and silly.”

The new year saw him heading out for another tour across Australasia. The crooning troubadour finally back out on the road, in his happy place once more. (Gareth Shute, 2023)

--

Marlon Williams had sung in te reo Māori since he was young but it was only in recent years that he began learning to speak it. Despite his limited proficiency, he felt himself drawn to writing songs in the language. He fortuitously befriended the musician and educator, Kommi, who also lived in the Lyttleton area and agreed to help him in this exploration.

Williams felt that using te reo brought a freshness to his work and he also drew influences from popular waiata of the past. This was particularly evident on his song ‘Korero Māori’ which had big group vocals and began with movement instructions like a Māori action song: “Hope, Ki raro, Hope, Paiahahā!” (hands on hips, hands by your side, hands on hips, attention!). The album Te Whare Tīwekaweka (2025) also made repeated use of the jingajik rhythm of the “Māori strum”.

There were also many touchpoints for those with a limited understanding of te reo. The lead single ‘Aue Atu Rā’ used words and phrases that were well known such as “moana” (the word for “sea/ocean” made popular by the film), “aroha mai” (“sorry”/ “have mercy on me”), and “titiro mai” (“look at me”, as often used by school teachers).

It was followed by a duet with Lorde (‘Kāhore He Manu E’) that featured a striking vocal performance from the pop star. His participation also brought in a wider audience, helping the song race past a million streams.

The process of making the album was captured by director Ursula Grace Williams for a full-length documentary film, Ngā Ao E Rua (2025). It took a fly-on-the-wall viewpoint, showing Williams moving from hectic overseas tours back to quiet songwriting sessions with Kommi at his home. They moved to a rural hall in Haast for the album sessions, with Williams’s backing band The Yarra Benders and co-producer Mark Perkins, aka Merk.

The film received strong reviews, with The Spinoff saying “it feels like quietly witnessing a piece of history,” and RNZ awarding it four-and-a-half stars. The album was even more of a triumph, debuting at No.1 on the New Zealand charts. The language may have changed, but Williams’s singing and songwriting reached new heights and had all the more resonance for those who had followed his journey as a Māori musician. (Gareth Shute, 2025)

On 29 October 2025 the song 'Aua Atu Rā', written by Williams and Te Pononga Tamati-Elliffe (KOMMI), won the APRA Silver Scroll. It was the first time a song with lyrics completely in te reo won the award.