Their song ‘Lockdown Lullaby’ helped audiences commune over the shared experience of estrangement recently endured. Reminding everyone that Covid didn’t happen in isolation, ‘Daily Dose of Sunshine’ was about Tony’s experience of receiving radiation therapy for prostate cancer; prefacing the ripping instrumental with this knowledge turned it into a vital conversation starter for some of the men in the audience.

The response was rapturous in every hall that held them. The East Coast Bays Folk Club delivered a standing ovation. “I think that was a first for this club [which] has been running for about 30 years!” enthused fellow folkie Kath Worsfold of that honour.

Across the Great Divide bridge social and geographical spaces

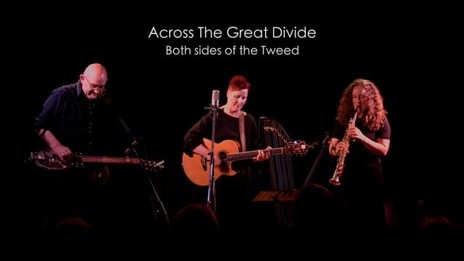

In these times where acceptance of cultural diversity is continually under threat, Across the Great Divide employ their timeless music – folk covers and original compositions – to bridge the social and geographical spaces between themselves and their listeners. Weaving together sounds from the disparate Celtic, Americana, and Swedish musical traditions of their members, the band cares as much about living their sound as they do about recording it.

Often referred to as Aotearoa’s finest dobro player, Tony Burt is president of the Wellington Folk Festival, and owner of Curio Film and Music, operating the Kettle Wink recording studio. He runs an annual Americana music festival Mid Winter Holler. He is a documentary filmmaker and soundtrack composer.

His early family life was “totally non-musical,” he says. “They were into rugby and listening to 2ZB – Mrs Mills and The Archers. Our records consisted of The Sound of Music – still one of my favourite films – Val Doonican, and Noddy. It was very limited. I distinctly remember strumming my first guitar at a marae, and thinking, ‘Oooh, that sounds nice,’ and then thinking, ‘I want a guitar!’ I might have been 12 or so when I got a guitar for Christmas. My parents have a cassette recording of me opening it. Then, I just had this feeling, ‘I just wanna learn.’ I went down to a local teacher, and I was like a pig in muck. Dad would be banging on the stair rail at three o’clock in the morning, ‘Shut up!’ The teacher would be trying to learn new things to teach me … It was just a progression from there, getting into rock bands.”

There were school bands like Argosy (“playing your David Bowie stuff”), and a gig at the Upper Hutt mall (“getting the plug pulled by the old lady in the bookshop who thought we were making an awful racket”). Argosy played at the Maidstone Park in Upper Hutt with the newly formed Crocodiles. The Upper Hutt Leader lauded Argosy’s performance, adding – as an afterthought – that “the Crocodiles played as well”. That still makes Burt laugh to this day, because he could see they were brilliant.

He became involved in Clive Cockburn and Val Murphy’s 1971 rock opera Jenifer. “It was a collection of people up in Stokes Valley. I was 17, but the musicians – guys from the music scene in Wellington – were all older. So, I got introduced through my friends, who were ten years older, to the likes of Clint Brown, Ray Ahipene-Mercer, Rockinghorse … All these artists were amazing influences. Then, on the side, we started this band, Madlight.”

Madlight played around the scene, at venues such the Terminus Tavern, on the corner of Courtenay Place and Taranaki Street in the early 1980s. Burt still likes to wear a T-shirt featuring a playbill for the Terminus, boasting an impressive roster of “LIVE BANDS EVERY NIGHT”, where Madlight sit alongside the Innocent, Blam Blam Blam, and The Steroids; and The Mockers and Midge Marsden are “coming soon”.

The stepping stone to film soundtracks came when Burt learned keyboards – mostly teaching himself – and branched out from rock into experimental and world music. He amassed numerous film and soundtrack credits spanning the first decade of the 21st century. He has also composed music for exhibitions at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, including E Tū Ake and Slice of Heaven in 2010, and Ka Mate in 2011.

Jones describes herself as “a folkie before I was born,” given that she gestated behind her Australian folk musician mother’s guitar. Her mother had put her VW and two pals on a boat to New Zealand in the early 1960s, to drive from pub to pub playing music by the likes of Peter, Paul, and Mary. When her mother got married, and became pregnant with Jones, she continued to play guitar, strongly influencing the future of her unborn child.

“I was inside, with only my mother’s skin between me and the guitar,” says Jones. “I think music has been that natural for me. When people say to me, ‘You’re so creative,’ or ‘You’re so great at music,’ or whatever, it feels such a foreign thing, like they’re saying, ‘You’re so good at breathing.’ It feels like this is how it really ought to be.”

we’ve somehow created this gap between everyday life and music, says Jones

She recalls parties, when she was a child, where her mum and uncle would be playing the guitar. Her Dad loved to sing around the house. “We just had music all the time,” she says, smiling. “We’d have a music conversation, and then we’d have one about the Weetbix, one about school … It wasn’t separate from our lives. And I think that’s the way it used to be with clans … or in Africa – tribal music – they just have it. Like Māori used music for healing, it’s just part of what they did. It wasn’t something separate from everyday life. I think we’ve somehow created this gap. Let’s bring it back down to earth and close that gap.”

Jones left Aotearoa for an OE which saw her waylaid in Edinburgh for 14 years, assimilating as much Scottish music and culture as she could. It was there the multi-instrumentalist began playing the instrument she (as “The Harp Lady”) is most recognised for: the clarsach, aka the Celtic harp. She also ran a popular weekly folk and traditional session, and established a music school. She still teaches via her Children’s Music Centre.

A couple of years after returning from Scotland in 2011, she began noticing Burt in their shared music circles, leading to email communication, and – eventually – the suggestion of dating. She thought the very public space of Auckland’s Mission Bay would be a good first place to meet, “so I could get away if I wanted to,” she laughs. It turned out she didn’t want to get away at all.

Both of them brought instruments, and Burt remembers it like a scene from a movie. “It was a balmy summer evening, and we sat on the park beach, with the dobro and the harp, playing some music, and all the families and kids would come along and sit down.”

“It was great,” recalls Jones. “I didn’t really realise what a scene the harp made when you turn up.”

Jones had recently met Swedish soprano saxophonist Hanna Wiskari Griffiths, who lived around the corner from her. Wiskari Griffiths grew up with Scandinavian traditional music. After attending her first “Ethno” festival as a teenager, she went on to become an artistic leader for the movement in Sweden, Australia, and Aotearoa, where she has lived since 2016.

“I loved her music,” recalls Jones. “We just never had that kind of music in New Zealand, and I love European music, I’m very open to it – the stranger the better. So, just because she was living around the corner, I said, ‘Hey, we’re making an album, and we’d love to have some sax on some of the tracks. Would you like to come and play on it?’”

Burt recalls: “The first album had all these other really cool musicians from Scotland, Israel, Ireland, Australia … ” Among a dozen guests, Wiskari Griffiths became something more. Regular feedback declared that Hanna was “the glue” that bound Burt and Jones’s special sound together.

“She’s such an amazing player,” says Jones, “the way that she fits her frequencies around our frequencies.” And she’s not speaking only of musical frequencies. “The biggest thing Tony and I share together is the feeling of inclusiveness and community, and that’s the thing we both feel, and work in, in our lives together. So, whenever we play music together, even though he has come from a different tradition, we come together, and we promote that inclusivity and community thing.”

Wiskari Griffiths’s work with “Ethno” highlights how equally matched to this vibe she was, inviting natural assimilation into Across the Great Divide.

“The three of us, we live the message about community,” Jones says

“The three of us, we live the message about community,” Jones says. “It’s the band message, but it’s also our personal message too. At the end of the day, it’s all about peace isn’t it? Pulling the community in, and whakawhanaungatanga.

“People working for cultural cohesion through cultural understanding are also working for the end goal of social harmony and peace among people,” Jones continues. “I guess what we three have in common is cultural cohesion through cultural understanding. Across The Great Divide do this through music.”

Personally, Jones believes in and works towards two objectives.

“Understanding our individual whakapapa helps us to understand ourselves, and – by default – to understand others. When we understand our past, we can understand our present much better, which will have a positive flow-on influence to our future. Across the Great Divide gives me a vehicle and voice to offer an opportunity for our audiences to connect with their Scottish and Celtic whakapapa here in New Zealand, as I have done myself – an opportunity to share the taonga which is our whakapapa.

“I also believe that – currently – creative outlet, or art, is seriously undervalued in New Zealand society (especially in the education system), and that is why I am working to push it in schools.”

She and Burt present Unity Through Diversity music sessions at schools to further this end. “I believe that, when we are balanced with intellectual and creative processes, we are much more able to work confidently with peace and harmony in our communities,” says Jones.

Through touring extensively around Aotearoa, Across the Great Divide aim to put the ability to make and share music in the hands and hearts of everyday people, rather than on an unreachable shelf. When removed from any strictly formal context, their universally unique sound surprises audiences.

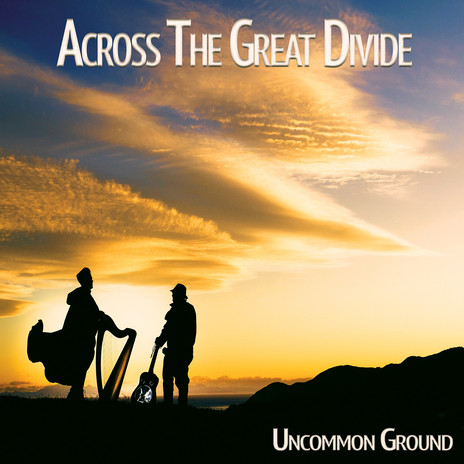

This was captured on their first album Uncommon Ground (2018); music critic Graham Reid described the results as capable of making one feel “transported in much the same way some of Mark Knopfler’s most grounded and understated Celtic work can do”. He further praised Burt as “a superb writer of slightly melancholy and wistful ballads”, while noting the diverse sources of traditional and other covered material. Their second album – Beyond Shadow (2021) – added tracks by Wiskari Griffiths (‘Längs Vägen’ and ‘Vyssa Lulla’) to the menu of folk, traditional and Burt-penned compositions, further broadening the Across the Great Divide sound. A third planned album intends to include more of her compositions, increasing the international scope of their work.

“In the folk world, people get used to it, but you take it out to people who haven’t heard it before, it’s something completely different, and it might blow their senses,” says Burt. “The folk community is a bit like the wizarding world, in that it happens outside the world of muggles. Arts on Tour broke it out, and presented it to an audience that had not heard that before.”