As she told the Listener’s Douglas Jenkin in 1986, Wednesday night in the Murphy household was the one night that Val and her sister Jill were forbidden to play Elvis. Her father, Jack Murphy, was a member of The Songspinners, one of New Zealand’s first recorded folk groups, and Wednesday was practice night in the family’s living room.

“We were very upset because we couldn’t play Elvis for a whole evening,” she recalled to Jenkin. “But I got to listen to what they were doing – if you can’t lick them, you join them. And I ended up playing their songs.”

When Val, fresh out of school, went to Wellington Teachers’ Training College she took her guitar and songbook with her. It was the early 60s and a wave of folk revivalists had made the music seem topical and exciting again. Val had learnt piano and taken singing lessons for a year. She told Jenkin: “What I had come to discover was that the [opera] words didn’t mean much to me and the folk music words did. They were very plain statements with an enormous amount of emotion in a few simple words rather than having the emotional quality in the music.”

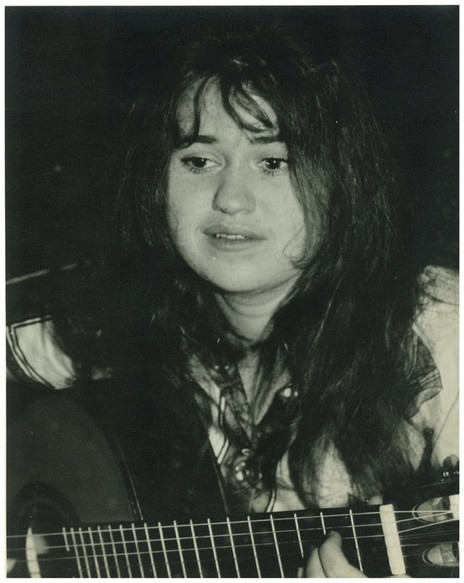

When she performed in a student concert at Victoria University, her powerful delivery made an impression. Afterwards she was tracked down at her hostel by Mary Seddon, granddaughter of Premier (Prime Minister) Richard Seddon and proprietor of Wellington’s well-known bohemian folk haunt the Monde Marie. “She said, ‘You must come down to my coffee bar darling.’ I thought, ‘Who is this lady?’

“It took me six months to get to her coffee bar and when I did, I never looked back. As soon as I got to the Monde Marie I thought, ‘there are people like me’ because they had folk singers – lots of magnificent people.”

It took Murphy six months to visit the Monde Marie coffee bar, “and when I did, I never looked back.”

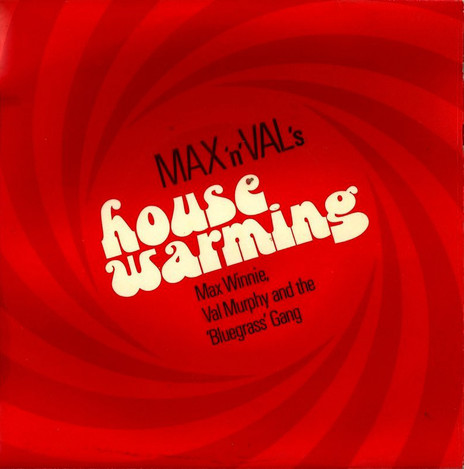

Val fell in with a community of mostly young local folkies that included Max Winnie and Nick Villard, and crossed paths with international folk celebrities. “Anyone who came to town ended up at the Monde Marie. William Clauson, I met him there, and Theodore Bikel. Judy Collins too. I remember she asked me about race relations in New Zealand and I talked to her for a long time. You’d sing sitting at a table for three hours – which people now say seems like a terribly long time – but it was great. I don’t know of anything like it today,” she mourned in 1986. “Gone are the duffel coats.”

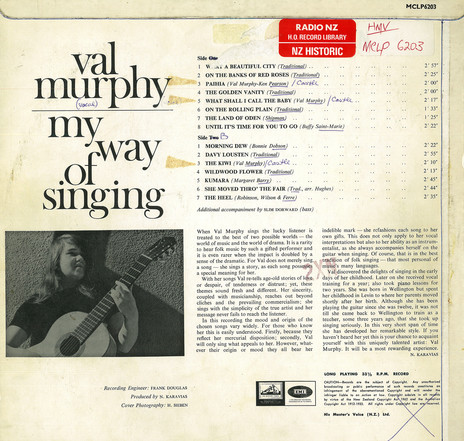

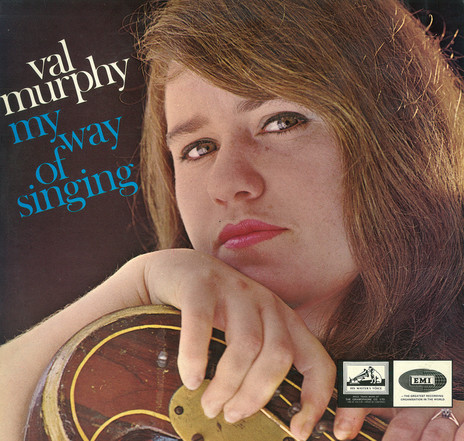

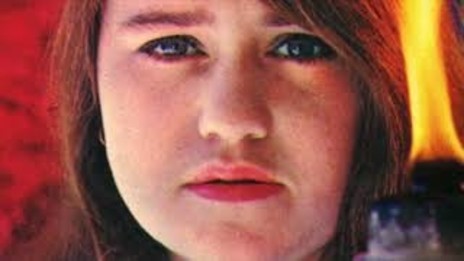

Perceiving a local market for folk and recognising Val’s talent, HMV signed her to a recording contract and set about making her first album, My Way Of Singing, released in 1965. Produced by Nick Karavias, the recording was spare: just Val’s voice and fingerpicked guitar, with occasional double bass by veteran session pro Slim Dorward. Val’s powerful soprano and strong feeling for the stories in the songs were easily enough to carry the material.

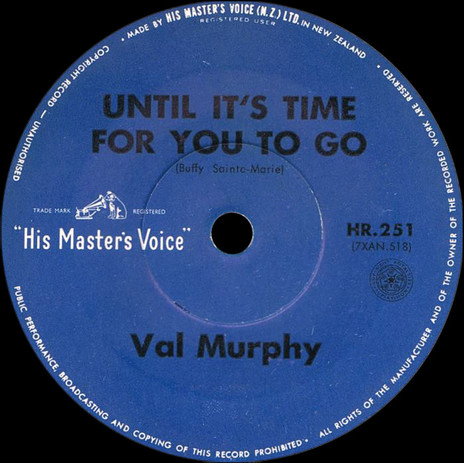

In his liner-notes, Karavias notes Val’s “sense of the dramatic” and the way she “refashions each song to her own gifts”, not just as a singer but also as a guitarist. In addition to songs from Irish, Black gospel and traditional English sources was contemporary material by Buffy Saint-Marie and Bonnie Dobson (the deathless ‘Morning Dew’), New Zealander Margaret Barry (‘Kumara’) and three originals: ‘Paihia’ (co-written with Ken Pearson),‘What Shall I Call the Baby’, and ‘The Kiwi’, in which she reflects on colonialism and her own Irish heritage.

But even at the height of her folk stardom, she was leading something of a double musical life. On Saturday nights she would put on earrings and a dress she had made herself and sing popular tunes with the house band at the Zodiac, one of only three licensed restaurants in Wellington at the time. Her closing number, a guaranteed showstopper, was always ‘Hava Nagila’. “It paid my rent for the week and I got a free meal”, she says. “After that I would go to The Balladeer, run by strictly folky Frank Fyfe and his wife. It must have been bizarre for him, but he loved that I did it.”

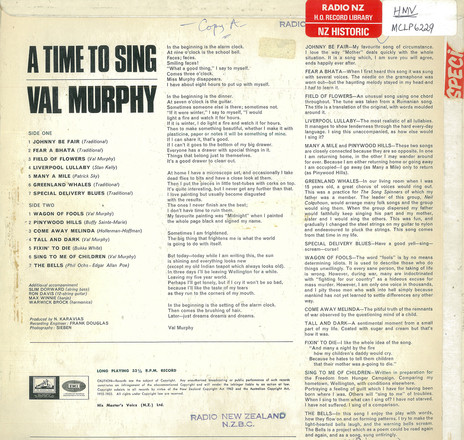

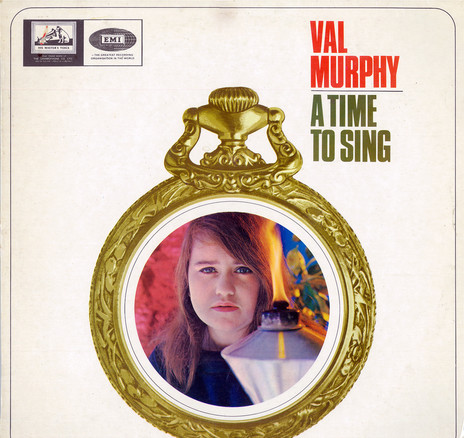

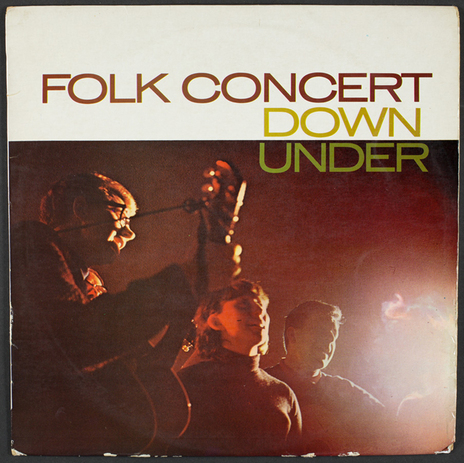

In 1965 Val appeared alongside several of her fellow Monde Marie habitués on Folk Concert Down Under, recorded live in front of an invited audience in the HMV studio. A second solo album, A Time To Sing, followed in 1966, drawing on a similar range of material to the first, her voice and nylon-string guitar occasionally bolstered by Ron Davis’s 12-string guitar, Max Winnie’s banjo and harmonica from Warwick Brock of the Christchurch-based Band of Hope Jug Band.

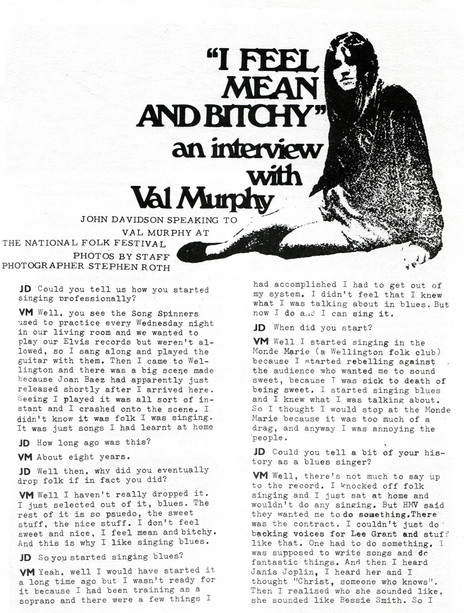

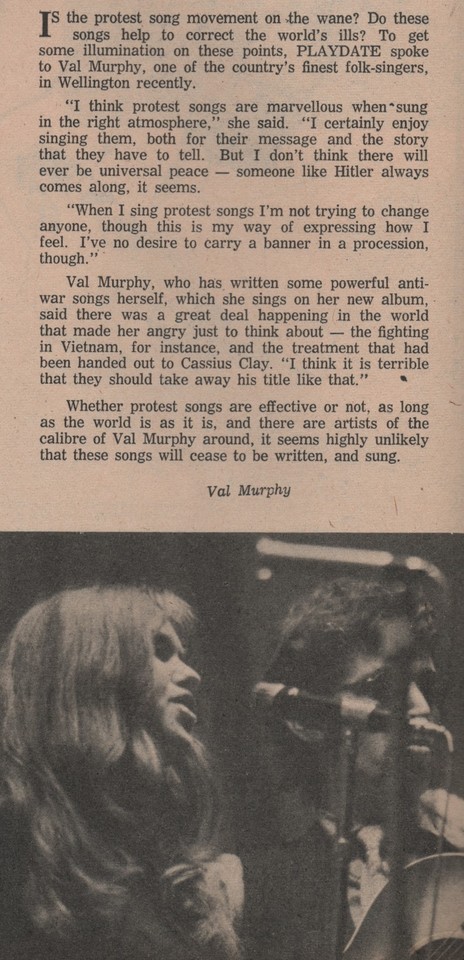

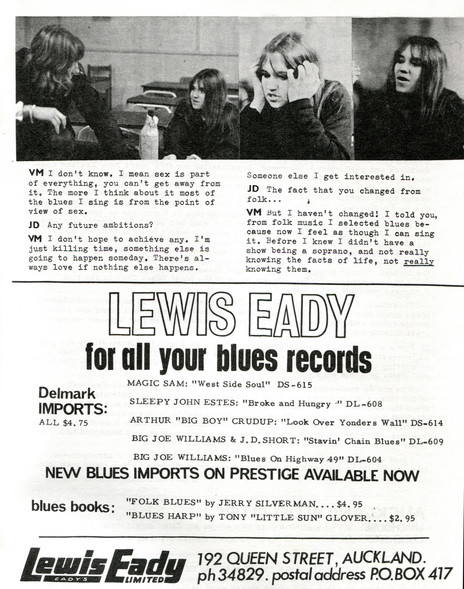

By the late 60s the folk boom had peaked. Some folkies were now going electric while others were turning their attention to the raw musical and emotional language of the blues, Val included. As she told John Davidson in an interview for the Auckland magazine Blues News, she gravitated towards blues because, of all the different styles of folk music, it seemed to best express her personal feelings. “The rest of it is so pseudo, the sweet stuff, the nice stuff,” she said. “I don’t feel sweet and nice, I feel mean and bitchy. And this is why I like singing blues.”

She had already recorded a heartfelt version of bluesman Bukka White’s ‘Fixin’ to Die’ on her second album. In 1968 she guested with the Band of Hope Jug Band on their self-titled album for the Kiwi record label, delivering a decidedly bluesy reading of Tracy Nelson’s ‘Walking To Chicago’ (backed by future economist Tim Hazeldine on piano). Still signed to HMV, though not having recorded as a solo artist since 1966, the label released a Val Murphy single in a blues vein: an arrangement of Skip James’s ‘Special Rider Blues’ backed by ‘My Man’, derived from the Billie Holiday song of the same name and learned from a version by Louise Spann on an album by her husband, Otis Spann.

Rather than emulate the originals, she would adapt blues songs to her own style, usually accompanying herself on her trusty nylon-string guitar. “I can’t pretend to be a black woman from the American South”, she says. “But I can take a song and wrap it up for myself, my version of it.”

A favourite of hers to this day is a Bessie Smith song, ‘My Sweetie Went Away’. “When I first heard it, I just about died laughing. When she sings ‘I’m like a little lost sheep’ she sounds like anything but a little lost sheep. She sounds like an axe murderer! But I adore the lyrics and the melody. And the humour.”

Sometimes Val sang backing vocals on recordings by other HMV artists, and it was in this role that she met musician Clive Cockburn from the group The Avengers, with whom she shared a producer in Nick Karavias. As Clive recalls in his memoir You Can Do It!, “We were [vocally] in perfect balance and to achieve that I was extremely close to the mic and she was a long way away which meant that she could sing and I couldn’t. We became great musical buddies and then we became a couple.”

When the two married, their wedding made the front page of the Sunday Times. “Val’s wedding dress was of cream-coloured crepe, Clive wore a trendy black velvet jacket, grey flared trousers and a dress shirt of the same material as Val’s dress,” the paper reported.

she gravitated towards blues because it seemed to best express her personal feelings

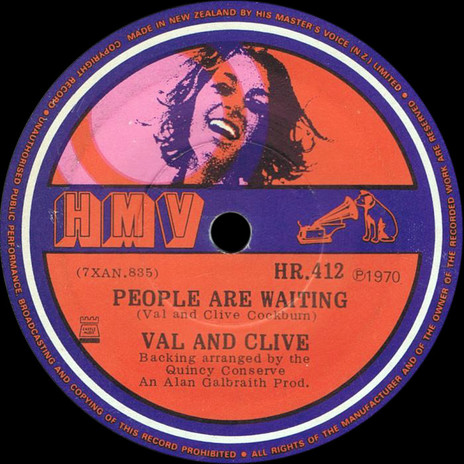

Their first collaboration had been on a one-off single, ‘Lovers of the World Unite’ b/w ‘There’s A Scarlet River Flowing’, a pair of faintly psychedelic folk-pop songs sung by Val, accompanied by The Avengers, and credited to Valeria Vengers. Released in 1969, it sank with little trace, but together Val and Clive continued to absorb and repurpose current sounds: Julie Driscoll, Janis Joplin, and early Blood, Sweat and Tears were among their favourites. Inspired by the brassy arrangements of Blood, Sweat and Tears, they co-wrote ‘Lucky For Me’, which they recorded as a duet, accompanied by The Quincy Conserve and released in 1970 as Val and Clive.

They also collaborated on a pair of ambitious musical theatre projects. The first was Jenifer, which was billed as “New Zealand’s first full-scale rock opera” and “the pop opera you’ll sing tears about”, though it was technically a musical with dialogue as well as songs. Librettists John Banas and Alan Farquhar strung the story together around a dozen songs by Val and Clive, who then wrote a few more to plug holes in the plot. The show, which ran at Wellington’s St James Theatre from 14-24 July 1971, featured well-known singers in the key roles including Graeme Collins of The Dedikation, Alan Galbraith, and Val herself; a rock band that included Tony Backhouse and Simon Morris of Mammal, and a live string section. During the season Val’s three-week old son Henry would sleep backstage.

After the success of Jenifer, Val, Clive and John Banas went on to collaborate on a full-scale rock opera, Valdramar: a post-holocaust fantasy involving an underground city, an evil wizard, and a heroic prince. This time, the entire narrative was delivered in song. In an age of Tolkien-inspired concept albums and prog-rock odysseys, Valdramar fitted right in. Its six-week Downstage season in late 1974 saw bravura performances by Andy Anderson, Robin Siminauer, and Val, among others.

During the three years it took to write and develop Valdramar, Val worked in other theatre shows, including live settings of Shakespeare in a Downstage production of As You Like It and portraying the Peanuts character Lucy in a staging of You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown.

When Spike Milligan offered to perform a fundraising concert for Downstage’s new theatre, the Hannah Playhouse, Val was asked to provide the musical interludes throughout the night. Though Spike caught her off guard, summoning her to the stage only moments after the show began, she was relieved to find the stage props she had requested were in place: an ashtray and a bottle of wine.

In 1976 she and Clive co-wrote the opening song for the South Pacific Festival of the Arts, held that year in Rotorua, and worked at the festival with a group from the Solomon Islands. The same year she appeared in BLERTA’s television series and feature film Wild Man, as both singer and actor, and played a role in Tony Williams’ film Solo.

Her teacher training merged with her musical career the following year when she composed an end-of-year musical for Ngaio School, the first of many children’s shows. She also began writing and recording children’s songs for Correspondence School broadcasts (in a regular series written and directed by Cormie O’Shea (wife of filmmaker John O’Shea).

She also found a regular slot writing topical songs for TVNZ’s Today At One, and sometimes appearing on screen singing backing vocals, along with the likes of Beaver and Tony Backhouse, on the pop show Ready To Roll.

By the late 70s her marriage had ended, and she had begun performing in concerts specifically by and for women. She sang at the 1979 United Women’s Convention in Hamilton and the 1980 Christchurch Women’s Arts Festival, where she also conducted workshops on Songs For Women.

In 1982 she was part of the Web Women’s Collective, which brought together a group of Pākehā and Māori women singer-songwriters including The Topp Twins, Mahinaarangi Tocker, Hattie St John, Jess Hawk Oakenstar, and Hilary King. “Women making music for women, singing the lives, the loves and the concerns of women,” as Broadsheet described it, the collective mounted a series of concerts and produced a groundbreaking album, Out of the Corners. Written, recorded, and produced by women, here was a record that, as Gordon Campbell noted in a Listener review, could “stand on its own feet without props or patronising”.

Her 1982 song ‘Punk Passion’ drew shocked reactions from some of her old fans

Though Val says “there was too much of me on it”, and self-deprecatingly tries to redirect listeners’ attention to tracks by Mahinaarangi Tocker and The Topp Twins, her contributions as singer, songwriter, guitarist and vocal arranger are essential strengths of the album. One highlight is her song ‘Punk Passion’. Though she performed it solo – just voice and guitar, like her first recordings from almost 20 years earlier, and drawing on the same extraordinary vocal and emotional range – it drew shocked reactions from some of her old fans. As she explained to Douglas Jenkin, one audience member came up to her after hearing it and said, “You used to sing such lovely songs.”

To Val, the song was “something that I had to write because I’ve never written a love song that was aggressive and also humorous. It’s very good to get to that point in your life when you can say to someone, ‘Look, if you muck me around, leave. Go away. I don’t want to know you.’ I think a lot of women can’t do without being madly involved in a relationship. But I know a few who actually quite like their own company and get over that. It’s often said, isn’t it, that if you can’t live with yourself, who can live with you? … But I chose to live alone before I got married and I like it. When my marriage broke up what I found out was that I had to go back to where I was years and years before, when there was only me and my guitar. And I started singing again.”

Even more raucous was ‘Give Us A Durry’, a politically-incorrect celebration of cigarette smoking, which she co-wrote and sang with Hilary King. But of all her contributions to Out Of The Corners, the most meaningful to her is ‘Love Song From Villa 6’, an intimate and deeply empathetic song based on her experiences playing for residents of Kimberley Centre for the Intellectually Disabled.

Living on the Kapiti Coast in the 80s, she met Paekākāriki-based pianist Gilbert Haisman at a party and, impressed by his abilities a blues player, began working with him as a duo under the name Wordsongs. They performed for several years, initially playing house concerts, then larger shows including a fundraiser to save Wellington’s St James Theatre.

Gilbert was struck not only by Val’s rich musicality, but also the raw honesty and spontaneity of her performances. “There was a blues she often sang, ‘My Man’, that starts ‘My man don’t love me / He treats me awful mean …’ and I came up with a little turnaround in the second bar, a G to G seventh thing, and I was proud of it. The first time I played it was one night on stage and she automatically changed the line to ‘He thinks he’s awful smart’, which I thought was hilarious and yet when I mentioned it later, she hadn’t even realised she had done it. That’s how in-the-moment she could be as a singer.”

In recent years Val has dropped out of live performing, but she continues to write. Among the songs she is proudest of are two that remain unreleased. One is ‘Mr Bible Man’, a quizzical riposte to door-knocking evangelists. And there’s ‘My Only Brother’, a heartrending ode to a vulnerable soul, which dates from the late 70s. She remembers performing it once at a women’s concert. When she introduced the song, its male subject matter drew disgruntled murmurings from the audience, yet by the end one could hear a few quietly weeping.