Ravi Shankar at Monde Marie, 1965 - Jane Seddon collection

Carried by groups like The Kingston Trio, a folk music “boom” reverberated around the world in the late 1950s, and it was heard as far away as Wellington, New Zealand. Over the next decade, the capital’s coffee bar folk scene would bubble over with its own special musical brew.

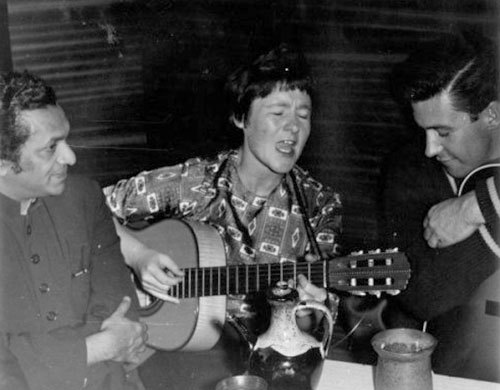

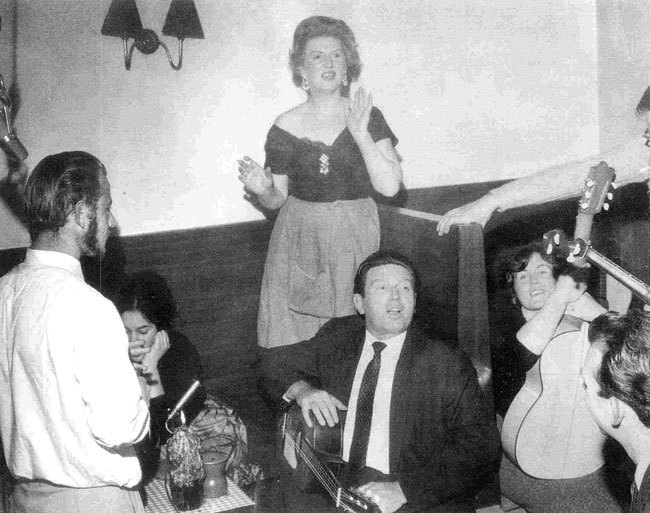

Mary Seddon and visting Austrian-American actor, and musician Theodore Bikel at the Monde in 1963 - Photo by Derry Seddon

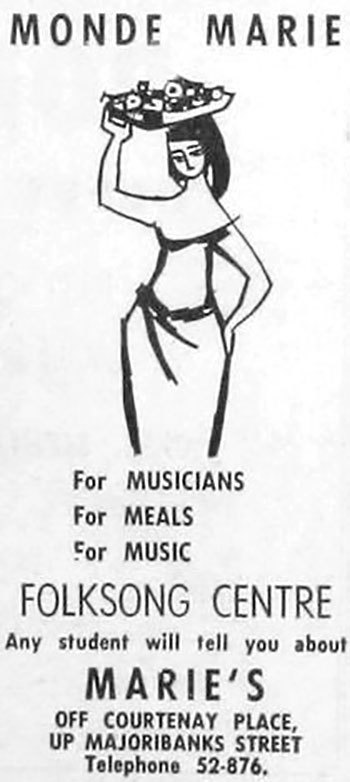

Folk music revivals in England and America had already influenced local music culture. New Zealand schoolchildren had been taught traditional English folksongs since the 1930s. In Wellington, varsity radicals dipped into a more left-wing folk repertoire after World War II, just as local airwaves began to feature the likes of Burl Ives and The Weavers. But the opening of the Monde Marie Coffee Shop in 1958 – the city’s first folk coffee bar – represented a watershed moment.

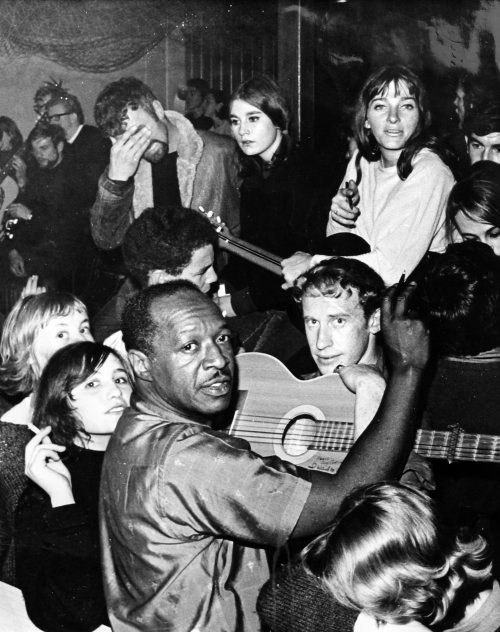

Josh White and Judy Collins (top right) at Monde Marie, 1965. In between them is Wellington folk singer Rod MacKinnon. - Jane Seddon collection

The Monde Marie Coffee Shop

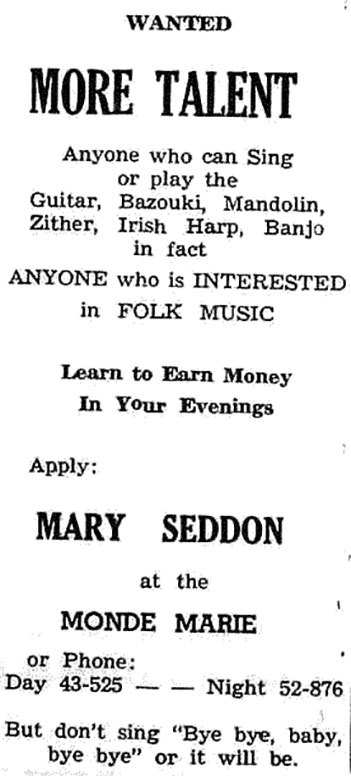

The Monde Marie’s proprietor was Mary Seddon (1924-2000), teacher, film reviewer for Truth newspaper and granddaughter of New Zealand Premier Richard Seddon. She had hitchhiked through Europe after World War II and wanted to recreate something of continental café culture down under. Coffee bars were no new thing in Wellington, but the Monde Marie, situated on the corner of Roxburgh and Majoribanks Streets, added some fresh twists.

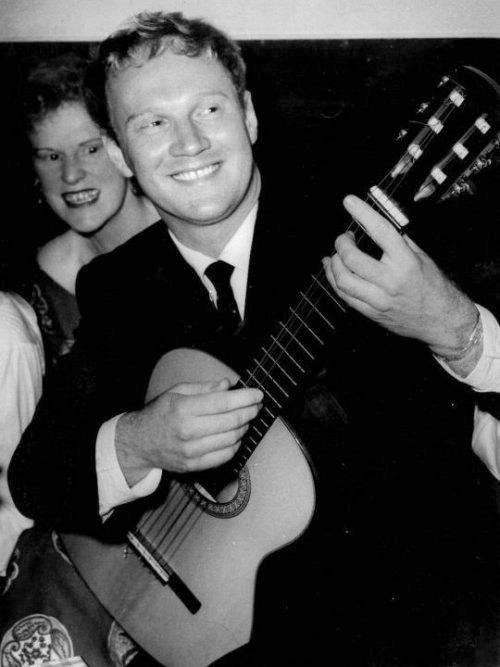

William Clauson and Rona Bailey at Monde Marie, early-1960s - Jane Seddon collection

the Monde’s ambience was strikingly bohemian.

For a start, the Monde’s ambience was strikingly bohemian – wall murals, fishing nets draped from the ceiling, wine-bottle candelabra – with Cona coffee, cheesecake and chilli con carne served by waitresses in short skirts and low-cut blouses. (“Cleavage sells coffee my dear,” one waitress was told.) And every night there was live folk music. “I sat in every coffee house, bistro, tavern, albergo, fonda and expresso bar from Lisbon to Cairo,” Seddon later explained. “Wherever I had been someone had always picked up a guitar or zither and sung.” In New Zealand, where pubs still closed at 6pm and cabarets mainly catered for dancing, it was a novel entertainment concept – and coincided nicely with folk music’s rising popular profile. “I had singers every night,” Seddon recalled. “It grew and we were the folksong centre of New Zealand.”

The Monde Marie. - Wellington City Council Archives Ref: 00138_0_10188

Live performance was a relaxed affair at the Monde. There was no stage as such. Singers and musicians performed, unamplified, from one of the booths near the counter, while the clientele conversed, sipped their coffees and sang along with the choruses. The establishment soon became a magnet for local songsters who helped fill the evening slots through to midnight. When the after-movie and theatre crowds flooded in on Friday and Saturday nights, the atmosphere hummed. Such was the venue’s popularity that Seddon eventually took over premises next door, doubling capacity to around 100 people.

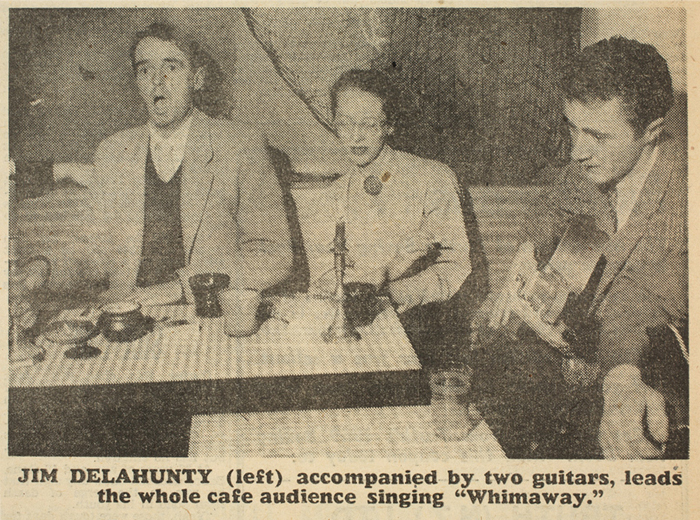

Long is the list of Monde Marie performers, but among the early roster were Terence Bryan, Vernon Wright and Dinah Priestley (later of The Chequers), Bruce King, Joan Prior and Peter Cape. Other key personnel included Max Winnie and Jim Delahunty (a member of early folk group The Sundowners). Auckland songwriter Willow Macky visited when she was in town.

Vernon Wright and 'Sabrina' at Monde Marie: Joy, 11 April 1960. In the 1970s and 80s Wright was a Listener staff writer.

Playing the Monde Marie was hardly lucrative – performers were paid a pound an hour, plus food and refreshments – but aspiring folkies embraced the opportunity to swap songs in good company.

During the Monde’s prime, “folk music” encompassed an eclectic repertoire, from ballads ancient and modern, sea shanties and French chanson, through to calypso and flamenco, with an overall emphasis on traditional material. There was also a New Zealand strand, including colonial songs collected by legendary political activist Rona Bailey, alongside Peter Cape’s vernacular ballads and other local compositions.

Jim and June Delahunty and Terence Bryan at Monde Marie: Joy, 20 June 1959

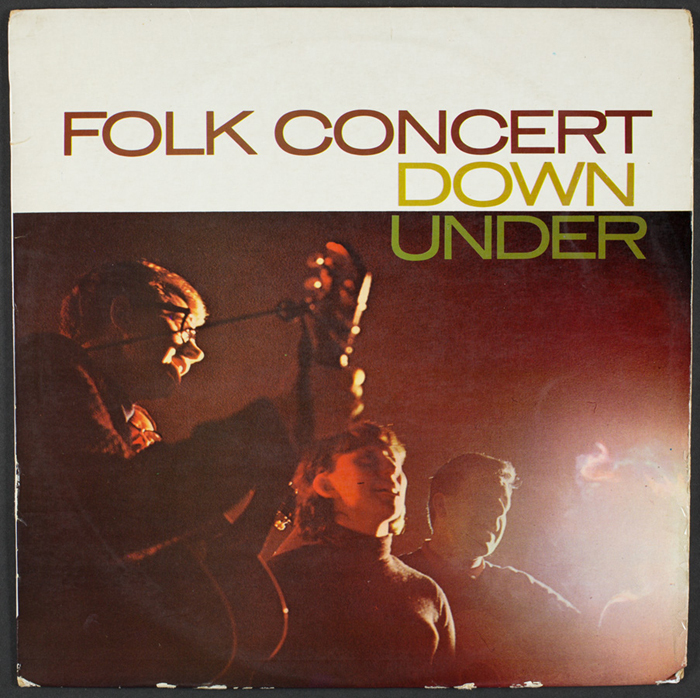

Guitars were a ubiquitous accompaniment, with banjos and the odd autoharp also chiming in. Small ensembles might feature tea-chest or double bass. The LP Folk Concert Down Under (ca.1965) captures something of the flavour with a cross-section of first and second generation Monde alumni: Don Toms, Val Murphy, Arthur Toms, Rod MacKinnon, Dave Whaley and others.

Val Murphy at the Monde Marie, Wellington, 1960s. - Wellington City Council Archives, BO001-6

What Folk Concert Down Under doesn’t represent – being recorded “live” at the HMV Studios – is the special ambience of the Monde itself, often enhanced by Seddon’s “special coffees”. Mostly the key ingredient was rum, sometimes brandy or mavrodaphne (Greek fortified wine), but any such alcoholic content was strictly illegal at the time. Nonetheless, word got around. Whenever American Navy icebreakers visited port, so the story goes, crew members would head to the Monde to break their drought if the pubs were closed. Special coffees, packed houses and rousing choruses of ‘Whiskey In The Jar’ made for heady sessions that could stretch into the small hours.

Monde Marie and Mary Seddon on Radio New Zealand National in 2010

Inducing further high spirits were post-concert sessions with touring stars. Famous visitors to the Monde include American singers Tom Lehrer, William Clauson, Paul Stookey and Mary Travers (of Peter, Paul and Mary fame), Theodore Bikel, Josh White and Judy Collins; Scotsmen Jimmie Macgregor and Robin Hall; Irish group the Dubliners; and Indian sitar maestro Ravi Shankar.

Peter Cape (with guitar) at The Monde Marie; beside him, harmonising, is visiting US satirist Tom Lehrer. - Jane Seddon collection

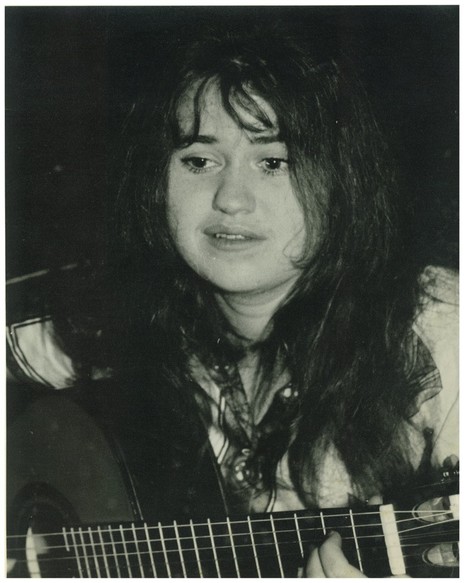

Larger-than-life locals such as deer culler-novelist Barry Crump also instigated some memorable scenes. And the coffee bar continued to nurture major talent, including folk-blues singer Marg Layton.

Advertisement for the Monde Marie from Salient, 1962

The Monde Marie’s most renowned personage, though, was Mary Seddon herself. No less barnstorming than her grandfather ‘King Dick’, Seddon orchestrated nightly proceedings with natural authority and outrageous humour. Whatever the challenge, she was indomitable. One legend has her bottling an unruly American sailor into submission one night, another ejecting two troublesome bikies with the help of a fire extinguisher. Even the police never quite managed to secure any licensing convictions. Seddon’s greatest bêtes noires proved to be the rival establishments who, by the mid-1960s, were looking for a slice of the folk coffee bar action – especially the new competition just across the road: the Chez Paree.

Advertisement for the Monde Marie from Salient, 1965

The Chez Paree

Mid-decade, folk music was burgeoning as a popular genre. Artists like Bob Dylan, Donovan, The Seekers, and Simon and Garfunkel were attracting huge audiences with original songs and innovative instrumental styles. In New Zealand, pop-influenced folk acts like The Convairs had taken flight and the country’s fledgling TV channels were commissioning dedicated shows, such as There’s a Meeting Here Tonight and Just Folk. The downtown Wellington scene was also heading in new directions.

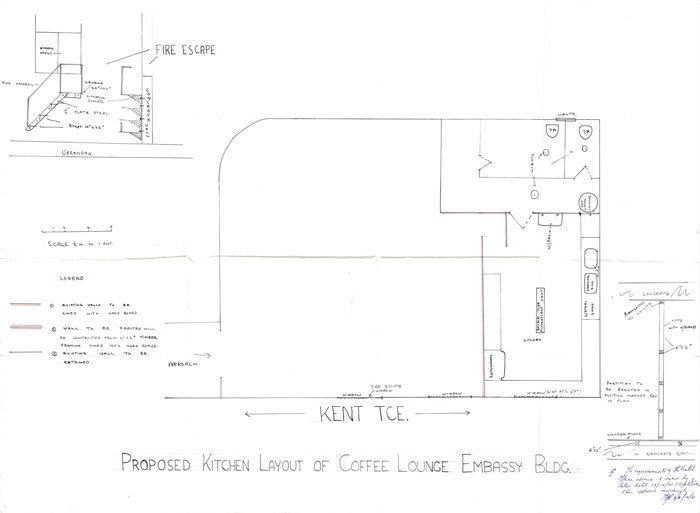

The original floor plans for the Chez Paree, part of Keith Dunshea's application to the council - Courtesy of the Wellington City Council Archives. Ref: 00058_205_C9382

Within two years there were reportedly over 80 coffee dispensaries operating.

Between 1961 and 1963, the number of coffee bars in the city virtually doubled, and it kept rising. Within two years there were reportedly over 80 coffee dispensaries operating. One of the new enterprises was the Chez Paree, established in 1962 in the Embassy Theatre building a mere 30 yards from the Monde Marie. Customers entered off Majoribanks Street, trekked upstairs then along a corridor with papier-mâché “cave” walls and into the main room, where they were greeted with further variations on a French theme: more fishing nets, poles wrapped with jute ropes, and red and white gingham tablecloths.

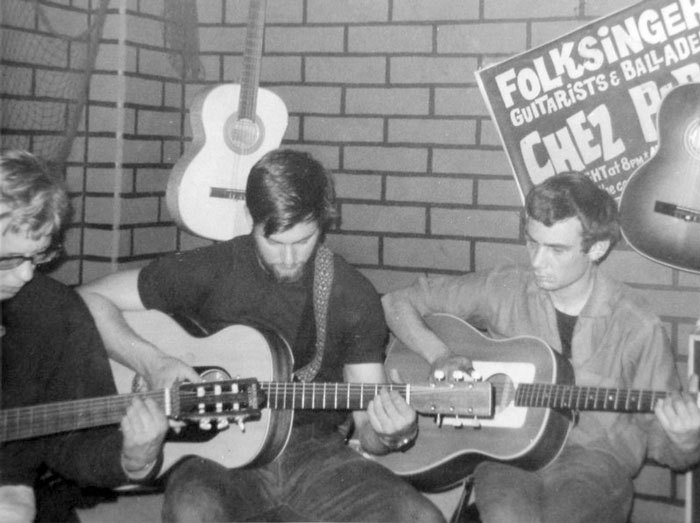

Bill Taylor, Bruce King and Ron Davis at Chez Paree, ca 1965 - Jane Seddon collection

The Chez Paree might have been accused by Mary Seddon of copying her “left right and centre,” but it did offer some genuine points of difference. For starters, there was a modest stage in the corner, with an actual microphone. The venue also had a straight-ahead appeal that attracted a younger crowd, still keen on acoustic folk but with ears tuned to more contemporary sounds. The Chez struck a chord. Despite derision from folk purists about its musical content (“superficial ‘Folkum’ together with the scraping of the Nashville barrel,” according to one critic), it probably succeeded more than any other Wellington coffee bar in the difficult task of making folk music pay.

Front cover of the ca.1965 LP Folk Concert Down Under (HMV MCLP 6205)

As it happened, the Monde and the Chez dipped into much the same talent pool. Arthur Toms, for instance, banned by Seddon after he was asked to run a welcome for Peter, Paul and Mary at the University Folk Club, became a Chez fixture for a time. Other seasoned troubadours also freelanced at the new spot over the road. With two coffee bars now presenting five hours of live music seven nights a week and various folk clubs springing up, Wellington was fast becoming a wandering minstrel’s paradise. Several other coffee outlets also dabbled in folk, including the Casa Contento in Eva Street, and later, the Matterhorn in Cuba Mall.

Chris Prowse and Gilbert Egdell at the Matterhorn, 1968 - Gilbert Egdell collection

The Chez Paree thrived through the mid-1960s boom period and beyond, the covers moving on from Dylan to the likes of Neil Young and Cat Stevens. Founding proprietor Keith Dunshea left to run a coffee bar in Surfer’s Paradise, succeeded by Rex and Connie McDowell. Among the many stage denizens of the later 1960s were Chris Prowse, Gilbert and Helen Egdell, Robbie Duncan and Alan Stephenson (soon reaching for stardom as Steve Allen). Others included rock entrepreneur Graeme Nesbitt and guitarist Robert Taylor who, before joining Mammal and Dragon, played acoustic sets upstairs at the Chez.

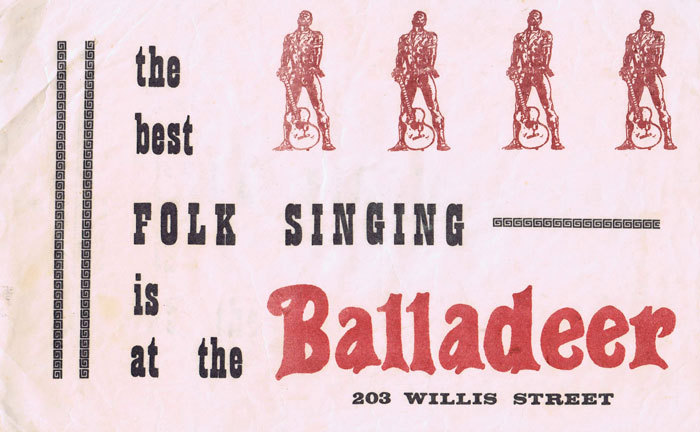

Promotional poster for the Balladeer - Robyn Park collection

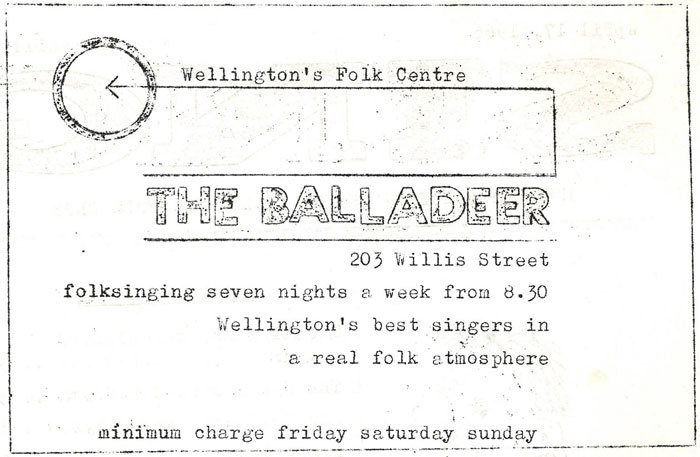

The Balladeer Coffee Tavern

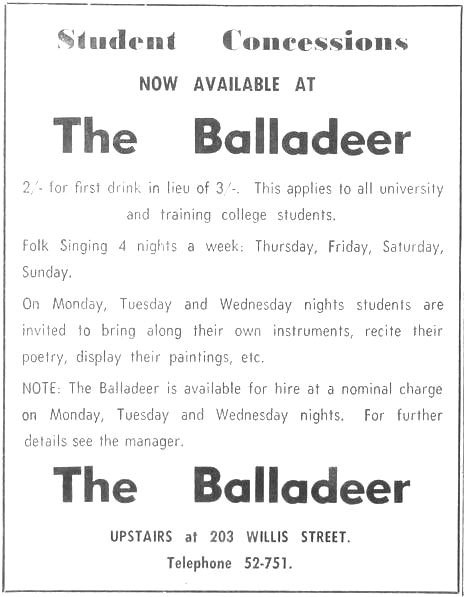

The history of Wellington’s third iconic folk coffee bar – the Balladeer Coffee Tavern – reflects other currents in the mid-1960s scene. These included the belief that folk music deserved to be taken seriously in its own right, whether as DIY music philosophy, “music of the people” or traditional heritage. Why should singers have to compete, as one commentator put it, with “the cacophony of 50 people shouting at each other over the clanging coffee cups and cash registers”? The various small folk clubs around Wellington that emerged during the early 1960s were part of the grassroots alternative. The Balladeer was another.

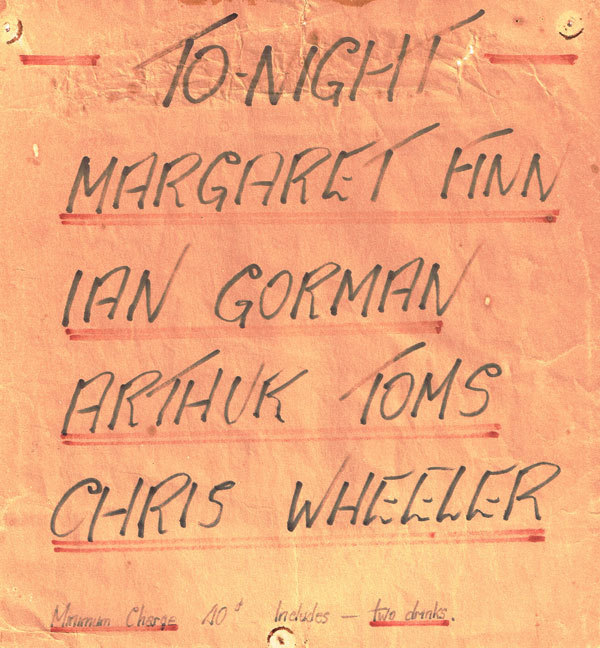

Concert line-up for the Balladeer, 9 September 1967 - Robyn Park collection

The Balladeer was founded in March 1965 by Don King and Martin Books on the former premises of the Green Door, above a Chinese takeaway in upper Willis Street. King was a classical guitarist and folksinger himself, sealing the venue’s credentials as “by folkies, for folkies.” After the Balladeer quickly ran into debt, Australian émigrés Frank Fyfe (1936-1997) and Mary Fyfe took over. Mary had been working at the Monde Marie, when Seddon asked one day if she fancied her own place across town and offered to absorb existing liabilities into the bargain. In return, the Fyfes would mind the Monde occasionally.

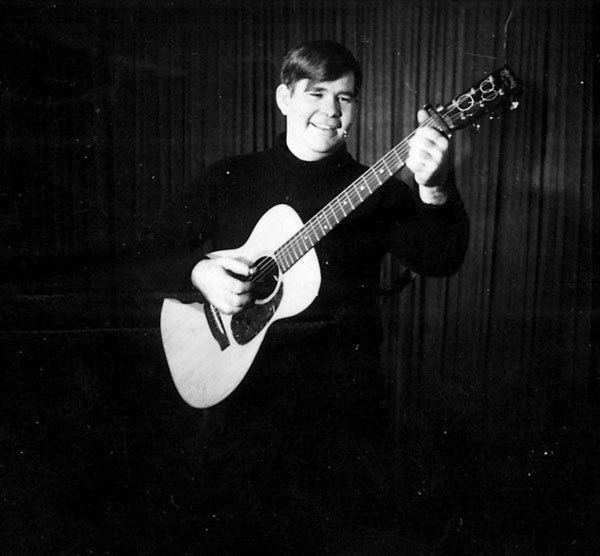

Frank Fyfe at the Balladeer - Mary Fyfe collection

The Australian couple had arrived in New Zealand the previous year, already veterans of the Brisbane bush music scene. As well as printing club newsletters, Frank Fyfe had run an underground press turning out anti-nuclear tracts; both Fyfes were members of CND and the Australian Labor Party. They also knew heavyweight folklorists like John Manifold and the interest in folklore would surface again in Wellington.

Advertisement for the Balladeer from Salient, 1965

Humble compared with the other coffee bars, The Balladeer’s furnishings initially consisted of little more than cushions and mattresses arrayed on the floor. When furniture did arrive, it came in the shape of homemade wooden forms and trestle tables. Similarly spartan were the refreshments: coffees, ‘Jamaica punch’ (Coca Cola with rum essence), and the mandatory toasted sandwiches. The venue opened only in the evenings after the Fyfes had finished their respective day jobs, but low overheads were one reason the Balladeer – or “The Bladder” as it was affectionately known – kept afloat financially.

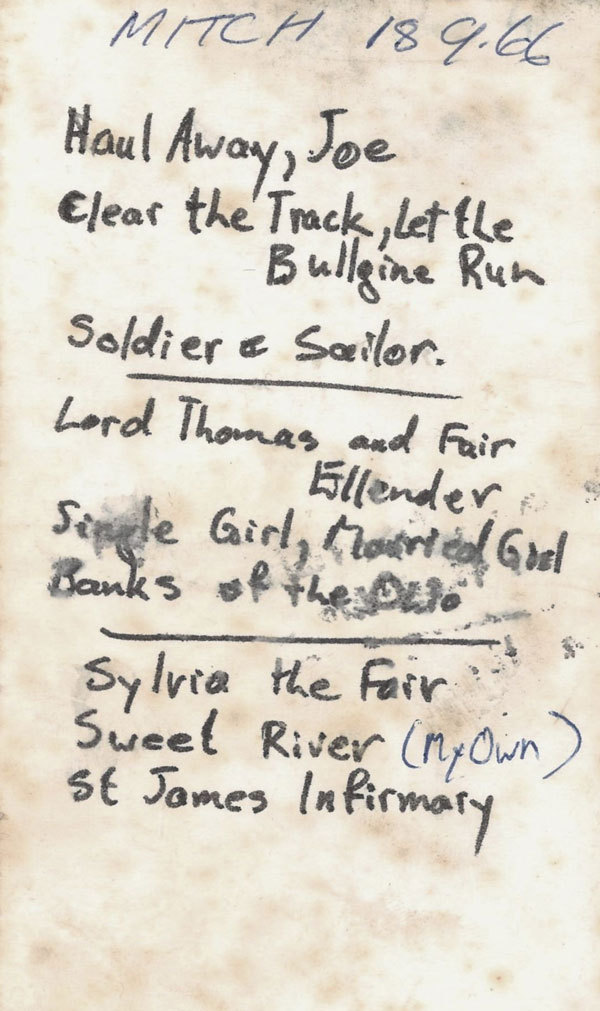

Mitch Park set list from the Balladeer, 1966 - Mary Fyfe collection

Fyfe enjoined members to collect songs, yarns and oral history from old timers

Filling the Balladeer stage were a swag of Monde Marie veterans and new faces, Frank Scaglione, Mitch Park, Jane Gardner, Jae Renaut, Jan Senior and others. Folkies visiting from other cities would regularly drop in to play. Frank Fyfe himself became an adept performer, leading the house in lusty choruses of Australian bush songs. If there was a touch of anti-commercialist folk purism in the air, the venue still generated its own social frisson.

Frank Fyfe was also involved with several influential initiatives, helping bring the Wellington Folk Club into formal existence, printing its bulletin and hosting sessions at the Balladeer. He lent a hand organising the city’s annual folk festival, inaugurated in 1965. Another pioneering venture was the New Zealand Folklore Society. Noting the low proportion of local songs in the New Zealand folk movement, Fyfe enjoined members to collect songs, yarns and oral history from old timers. Several branches sprang up in other cities and research was published in a journal, The Maorilander.

If any Wellington coffee bar carried the banner of protest song, it was the Balladeer. Anti-establishment sentiment came through with a repertoire that included both classic “rebel songs” and topical political comment. Fyfe also got printing. The Vietnam War was emerging as the left-wing cause célèbre by this time and, during US President Lyndon Johnson’s October 1966 visit, the Balladeer itself came under police scrutiny. The coffee bar was raided during a city-wide search for a hunting rifle and several regulars convicted for daubing unwelcoming messages like “Stuff LBJ” on the cable car terminus.

Economics proved a greater long-term challenge, though. The Balladeer’s uncompromising musical approach had always ensured the customer base remained more dedicated enthusiast than general public. In November 1967, with a new family arrival and a rent increase looming, the Fyfes reluctantly closed the doors.

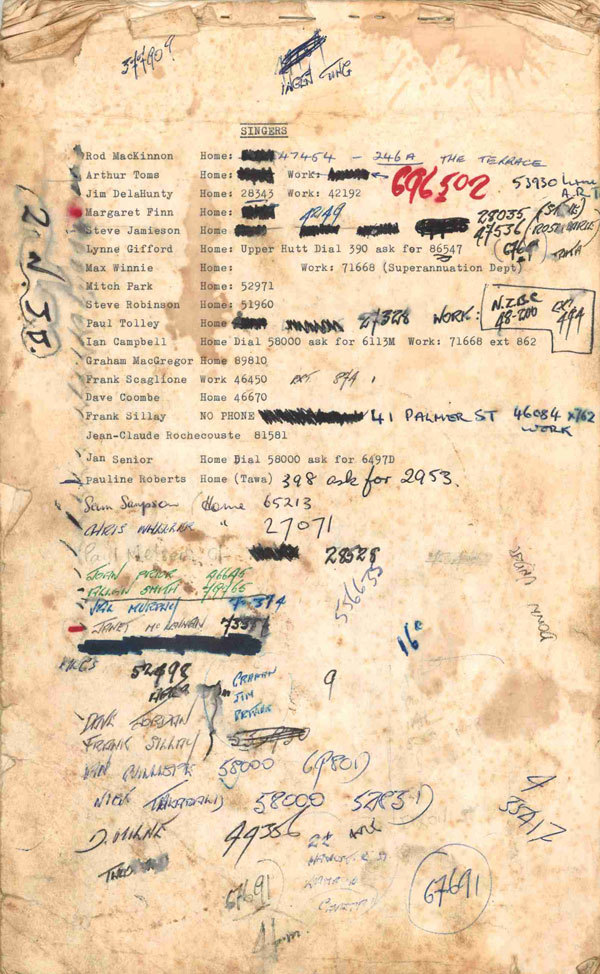

Balladeer singers contact list. - Mary Fyfe collection

Wider changes were also afoot. Licensing laws changed in 1967, allowing pubs to stay open until 10pm and opening up new evening entertainment possibilities. Local folk music was also diversifying into jug bands, old-time, bluegrass and blues. In Wellington, the University club was booming (500 members by the decade’s end) and plugging into a rootsier electric scene. Meanwhile, the Wellington Folk Club continued its peripatetic existence before finally establishing a permanent headquarters, the Wellington Folk Centre, in 1970. The era of the folk coffee bar was naturally drawing to a close.

Advertisement for the Balladeer, 1965

The curtain came down on the Monde Marie in 1970: Mary Seddon eventually found all the competition too much. The Chez Paree continued with live music until mid-decade, briefly serving as the capital’s first punk venue (aka the Mindshaft) in 1978. But the original spirit of the folk coffee bars lives on in the Wellington region’s various folk clubs and performers, immortalised in stories, poems and songs like Peter Cape’s ‘Monde Marie’:

What I want is the sound of Segovia

An Ives or a Clauson-to-be

And to hear them my choice is the guitars and the voices

I find at the Monde Marie.

New Zealand Folklore Society membership form, 1966

–

Thanks to Jane Seddon, Wellington City Council Archives, Salient, National Library Of New Zealand and the New Zealand Electronic Text Collection.

Michael Brown’s MA thesis on folk song collecting in New Zealand can be read here.