AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

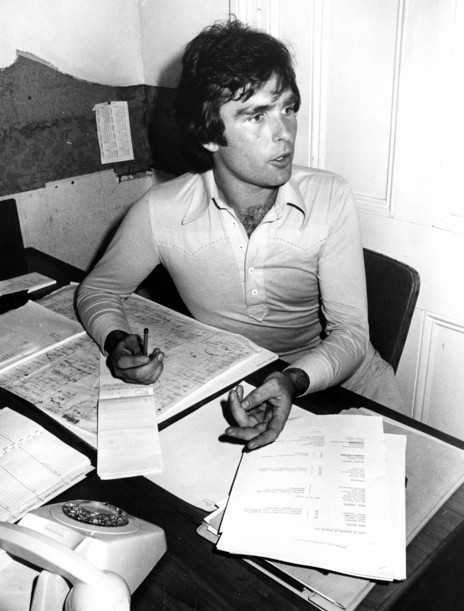

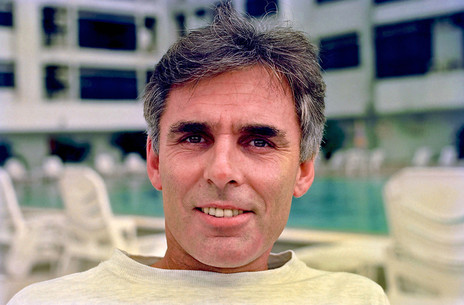

Graeme Nesbitt

Graeme John Nesbitt was born in 1950, the eldest of six siblings, and spent his early years in Kohukohu on the Hokianga harbour, where his father was postmaster. At nights he would tune in to the Lever Hit Parade on radio.

At Rawene High School he took guitar lessons from teacher George Sutherland. He had a strong academic bent and – after teachers told his parents that they felt unable to extend him to his full potential – he was sent as a boarder to Whangārei Boys High, where he studied Latin, among other subjects.

There he met Raureti Reginald Ruka Korako, better known as Reggie Ruka, a young singer and guitarist who had a strong musical influence on Graeme and would later front numerous groups both here and in Australia. Graeme would often accompany Reggie to gigs. Sometimes they would travel to Auckland, where they would catch local bands in the youth clubs or see international stars such as The Beatles.

In 1965 Graeme’s father was promoted in the postal service and the Nesbitt family moved to Upper Hutt. The Nesbitts’ new home was a wing of the old Trentham Military Camp. Graeme’s room was a former laundry, some 30 feet long, where he could practise his music without disturbing anyone. He acquired guitars, an electric bass, violin, and saxophone, all of which he mastered to some degree.

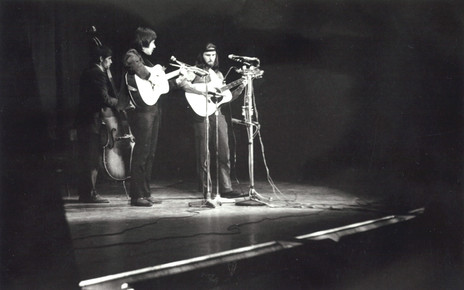

His musical preference, formed in part by the Māori singers he had grown up amongst in the North, was for country and blues. At Upper Hutt College he met more musicians, including Ray Mercer, a guitarist who would later play with national hitmakers The Dedikation, and Alastair Richardson who became a member of The Fourmyula. With classmate Christine Clocek he formed a folk duo, Los Pescadores. By the time they had finished school they were performing in Wellington folk coffee houses such as the Chez Paree and Monde Marie.

At Victoria University from 1968, he quickly became involved in the cultural life of the campus

He started at Victoria University in 1968 and quickly became involved in the cultural life of the campus. He joined the University Folk Club as both an organiser and performer. He also kept busy off campus, assisting promoters when international folk stars such as Julie Felix and Peter, Paul and Mary came to town.

In 1969 he launched the Victoria University Rock and Blues Society, and began promoting concerts of his own in the Student Union Hall. These provided a platform for a new type of band that was starting to appear: electrified and loud, studiously uncommercial, drawing on blues, experimental rock and original material, they were sometimes referred to as “the underground”. Wellington bands including The Original Sin, Capel Hopkins Blues Dredge, and BLERTA forerunners The Acme Sausage Company all appeared at what Graeme billed as “Hard Concerts”, along with out-of-town visitors such as The Underdogs and Ticket.

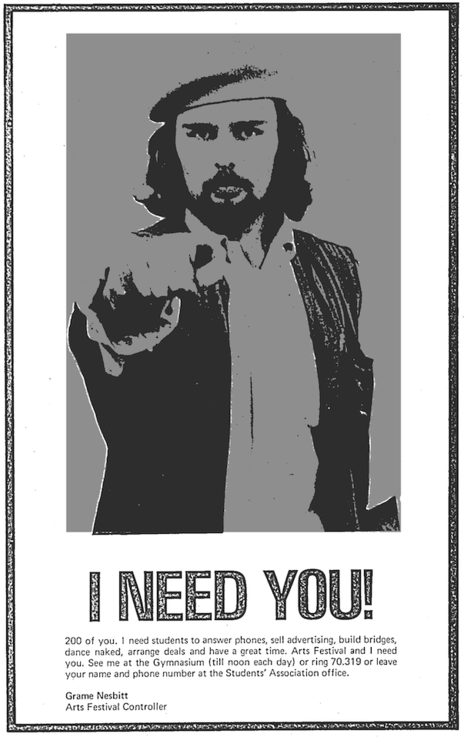

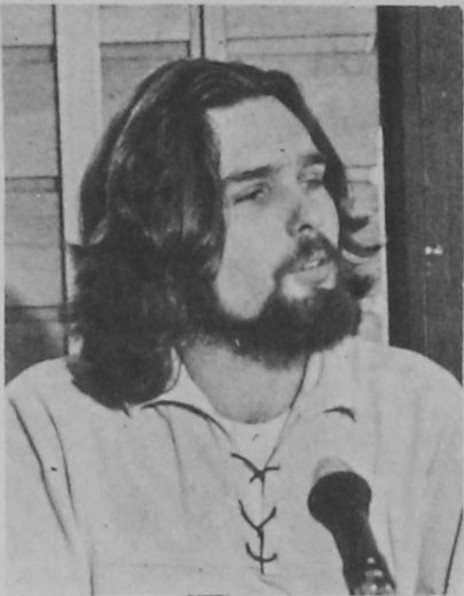

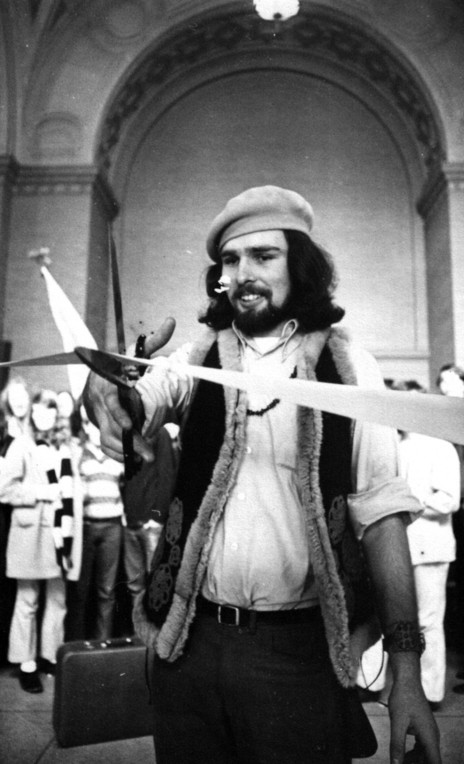

By this time he had begun to look something like a psychedelic Che Guevara: longhaired, bearded and often sporting a beret, an Afghan coat and purple socks. “It was very hard not to see Graeme around the university,” remembers Patricia Watson, a teenager from Christchurch who arrived in Wellington around this time, and would work closely with Graeme in the years to come.

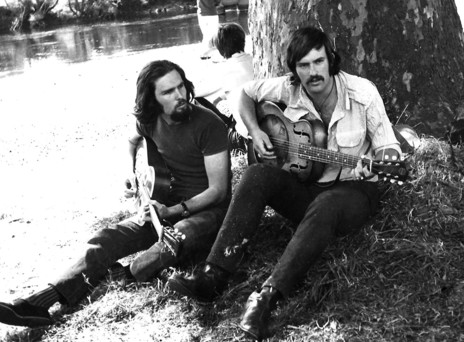

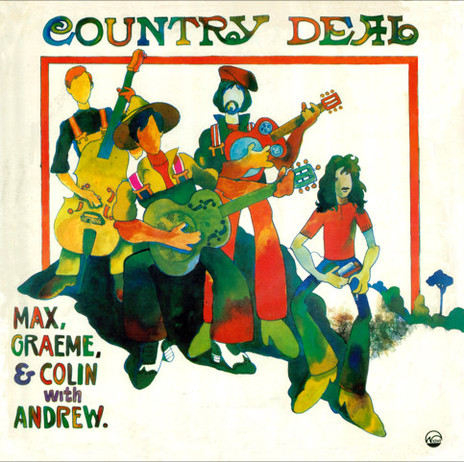

Graeme continued to make music of his own. With local folk hero Max Winnie and jazz bass player Colin Heath he formed Country Deal, specialising in blues, jug band and country songs. He also did a spell on guitar in Rick and the Rockets, an eclectic combo led by Rick Bryant, an up-and-coming rhythm and blues singer who would become one of Graeme’s closest friends.

In an unpublished memoir, Bryant described Graeme in this way:

Mercurial, jovial, Promethean, Dionysian, possibly definitely slightly Greek if you get my drift, he was considered extremely handsome by many, including himself. He seemed to be able to charm almost anyone of any age, class, style, belief system, race, culture, either or any imaginable gender, or I should probably say, sex.

He was also extremely intelligent, and, I realised some decades later, horribly insecure, and – this was well concealed – in constant need of reassurance, which luckily was never far away.

“Graeme was not a very good guitarist,” Bryant recalled. “He owned a wah-wah pedal, but one of us, well, Peter [Kennedy] mainly, would hide it at the beginning of practice if possible, and its battery would go missing quite often. But Graeme did know quite a few chords. When we wanted to write something, he’d play a B flat minor 7th. He claimed, and I think he may be right, that there is no better starting point. We didn’t actually ever finish a song, but he was right about the starting point. We were to do a lot of jamming with it over the next few years.”

Somewhere in this period Graeme discovered marijuana. In late 1969 he was appointed to a committee of the Students Association to look into the question of legalisation. Nesbitt advocated “controlled use” among those of legal drinking age.

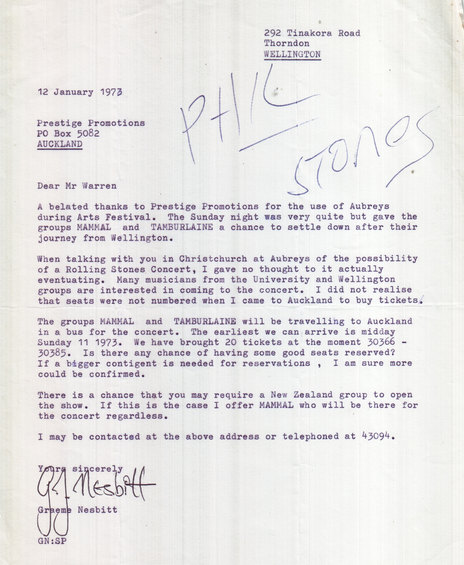

In 1970 he was elected Victoria University’s cultural affairs officer and appointed Controller of the National Student Arts Festival, which was to be hosted that year by Victoria. Normally run as an adjunct to the annual New Zealand Universities Winter Tournament, a sporting event with a fair amount of alcohol consumption on the side, the profile of the Arts Festival had been raised the year before when Auckland organisers replaced the traditional Saturday night hop with a “Freak Out” involving rock bands and a light show.

Commuters arriving at Wellington railway station were greeted by Mammal playing psychedelic rock

Graeme took this concept to the next level. On the first morning of the 1970 festival, visiting students and commuters arriving at Wellington railway station were greeted by the sounds of the recently formed Mammal (more on them later) playing psychedelic rock inside the station’s entranceway. The festival closed a few nights later with a concert at the Paramount Theatre headlined by another new Wellington band, Highway. Writing for Auckland student paper Craccum, Bruce Cavell judged it to be “the best local thing I’ve ever been to ... rock’n’roll played the way you wish it would always be played.”

The festival’s good vibes were dampened only by an incident in which a group led by Auckland student radical Tim Shadbolt attempted to tried to stage a spontaneous sleepover in the Student Union Building. When the squatters refused to leave, Nesbitt called the police, and Shadbolt and several others were charged with trespass, leading to accusations that Nesbitt was an “establishment pig”. There were other grumblings that he had lavished too much attention on the rock component of the festival at the expense of other art forms. Nevertheless, the event was widely hailed as a success and further established Nesbitt’s reputation as a creator of happenings. It even turned a profit for the Students Association.

Jim Stevenson, the first chairman of the National Student Arts Council, worked closely with Graeme around this time, put the event’s success down to Graeme’s unique skillset. “The key word – if overused – is charismatic,” he recalled in 2015. “He was able to imbue people with enormous enthusiasm. He was a unique thinker; he didn’t just borrow stuff. He had an absolute affinity with music and a deep knowledge, and that ability to have a vision and carry it out and take people with him. He was a live force.”

To light the Arts Festival concerts, Graeme had enlisted Peter Frater, a veteran of campus drama and music clubs who was now pioneering his own psychedelic light show involving 16 mm silent films and oil wheels: rotating cylinders filled with oil and food dyes which created colourful, cellular-type patterns that were projected onto a screen behind the bands. Frater’s light shows would continue to be a feature of Nesbitt productions, evolving into ever more complex affairs requiring multiple projectors and operators.

Patricia Watson met Peter Frater while working at Downstage Theatre and was drafted in to help. “Graeme and Peter would go off and have a big joint. They would give me a smoke and I was not half as experienced as they were. Then they would leave me up on the landing where the oil wheels were, and I’d be so stoned that I’d go to sleep on the floor.”

Over the next couple of years Graeme would feed the growing appetite for underground rock, promoting dozens of concerts on the Victoria campus, as well as in downtown clubs such as Lucifer’s and occasionally larger venues like the Wellington Town Hall and Opera House. He brought to Wellington out-of-town bands such as Split Enz, Space Waltz, Dragon, Butler, 1953 Memorial Society Rock’n’Roll Band, and Billy TK and Powerhouse, billing them alongside locals including Farmyard, BLERTA, Tamburlaine and Mammal.

“Those concerts were like a hub for everybody,” Watson remembers. “Those audiences were the same people who were at the protest marches, who were the counterculture of the time. I think the role of music in all of that can’t be underestimated. If you think of university as your home, it was right there in your home. You didn’t have to go anywhere, you just rocked up. And everybody went. That music in the academic institutions created part of the vibe and energy of those institutions and I don’t think that exists now.”

Graeme took on the task of managing Mammal – as much as anyone could

Graeme took on the task of managing Mammal, as much as anyone could. Though their raggle-taggle demeanour and challenging original material made them a less-than-commercial proposition and virtually unemployable on the lucrative pub circuit, he had a staunch belief in their musicianship and in that of Rick Bryant, who had become Mammal’s singer.

Though their personalities were almost diametrically opposed – Rick was shy and reserved, Graeme extroverted and upbeat – they also had much in common. Both were highly academic; Rick had graduated in English with first-class honours and had gone on to become a junior lecturer while Graeme studied Chinese, religion and ethnomusicology. Both loved American roots music. And both were keen on marijuana, which they had begun to sell, initially in small quantities simply to subsidise their own consumption, later in larger amounts to help fund musical projects.

Mammal were musically, if not professionally, ambitious. The Auckland-based Dragon, by contrast, were musically undeveloped but fixated on success, which impressed Graeme. In the 18 months they had been together they had already released an album, begun to work on a follow-up, and were ready to break out of the New Zealand circuit of campuses and clubs.

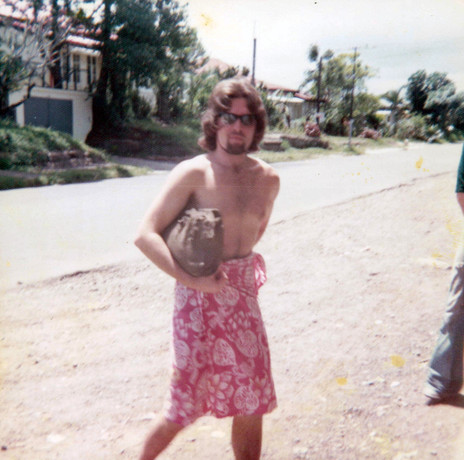

Dragon were impressed with Graeme too. Having witnessed his organisational skills on the campus scene, guitarist Ray Goodwin approached Graeme about managing the group. In 1974 Graeme took them on a tour of Fiji. At the aptly-named Golden Dragon nightclub in Suva, where the group spent much of their three-week say, they were forced to sideline their original material in favour of popular covers. Determined to give the originals at least one airing on the trip, Graeme booked a one-off event in a local hall, billed grandly as The First Suva Rock Concert. While Dragon’s self-penned songs went down little better there than they had in the nightclub, at least the opening act was a hit: Graeme Nesbitt, in a rented cowboy costume, strumming an acoustic guitar and singing a selection of country classics.

When Mammal split up towards the end of that year, Graeme manoeuvred Robert Taylor, Mammal’s star guitarist, into the Dragon line-up. Their next single would be a song of Robert’s, ‘Education’, produced by Graeme.

Having set their sights on Australia, Dragon planned a final tour before departing

Having set their sights on Australia, Dragon planned a final tour of New Zealand before departing. But after crossing Cook Strait, the band’s bus developed engine trouble, requiring expensive repairs. Graeme flew to Christchurch with the financial solution: a large quantity of cannabis, which he planned to sell. Goodwin collected Graeme and the stash from the airport but soon realised his van was being tailed by police. A chase ensued and Goodwin and Nesbitt were arrested and held in Addington Prison, awaiting remand. Goodwin was eventually discharged but Graeme was sentenced to two and a half years, most of which would be served in Wi Tako Prison, near Upper Hutt. After a few months he was joined by Rick Bryant, who had been convicted for dealing cannabis in a separate bust. They formed a prison band, Rick and the Rockbreakers. At one point they even shared a cell, where they discovered that between them they could recite the entirety of Shakespeare’s Hamlet by heart.

Before the bust, Graeme had been working on several music touring projects with Bruce Kirkland, his successor at Student Arts Council. With Graeme suddenly out of commission, Kirkland asked Patricia Watson, who had just finished a stint as front of house manager for the South Pacific Arts Festival in Rotorua, if she would step in. Almost immediately she found herself on the road with Canned Heat, trying to keep their alcoholic singer Bob Hite off the booze long enough to stand and sing at each night’s show. The band told her that when they had been informed their tour manager was called Pat Watson they presumed she would be a man. “They said ‘We’ve only had one female tour manager before and she is a heroin addict in Barbados now!”

While Pat was chaperoning the likes of Hite, Renée Geyer and Flo & Eddie, Graeme was plotting further musical events from his prison cell. By this time Dragon were in Sydney and had secured a recording contract with CBS. But they had also been befriended by Greg Ollard, a former Wellington cannabis dealer who was now part of the burgeoning “Mr Asia” heroin ring. He helped the band out financially and gave them easy access to hard drugs, of which drummer Neil Storey became a victim. After Storey’s death from a heroin overdose, Dragon recruited another former Mammal, Kerry Jacobson, and at last seemed to be heading for the stardom they had long sought. Graeme planned to bring them back to New Zealand for a triumphant celebration that would coincide with his release from prison.

Dragon returned to Wellington in style. Their homecoming concert at Wellington Town Hall (a double-bill with locals Red Hot Peppers) was attended by a parade of fans, fellow musicians, and characters from the campus underground. But with the group’s drug associations and Graeme’s own recent history, the event was being closely watched by police. Pat Watson, who had been promoting the concert from Graeme’s Willis St office, remembers seeing police cars parked outside the building, taking note of the comings and goings.

When the budget for the Dragon visit blew out, Graeme turned to a source of quick cash

When the budget for the Dragon visit blew out, Graeme turned again to the one source of quick cash he knew. One night, a few weeks after the Dragon show, he walked out of the office carrying nine pounds of cannabis and was immediately picked up by the police. Pat Watson received a midnight call. It was Graeme, in custody. “He asked if I’d take over managing the bands. He had Red Hot Peppers and a bunch of others with tours already booked. So all of a sudden, overnight I became the band manager, as well as going up and down to the jail every day to check with Graeme.

“People were ringing the office and asking, ‘Is Graeme there?’ and I’d go, ‘No’.

‘When will he be back?’ And I’d say, ‘He won’t be.’ ‘Where is he?’ And I’d say, ‘In jail.’ ”

She was also fielding odd calls from anonymous “friends”. The cannabis Graeme was caught with had come from the Mr Asia drug ring. Now Mr Asia associates were scheming to secure Graeme’s release. She remembers “unknown callers ringing with harebrained schemes. They would say, ‘We’re going to show it is intimidation. We’ll drive past the office, you’re going to get under the desk and we’ll fire bullets through window ...’ ”

Another plan involved landing a helicopter in the prison yard, rescuing Graeme and squirrelling him out of the country. Pat would relay these stories to Graeme who just shook his head and said to tell whoever was calling that he would be staying right where he was, thanks. Which he did – though he was eventually moved to Rangipo Prison, and finally Mt Crawford, from which he was released in 1978.

“It doesn’t matter how educated, smart, or sensitive you are, there’s still a lot of work to be done when you’ve been through an experience like jail or war,” Graeme said to interviewer Peter Fantl in the July 1984 issue of Cha Cha.

For Graeme, the work had begun even before his release. During his time at Rangipo he had received a visit from Colin Knox, a town clerk in Wellington with whom he had previously been on the executive of the Victoria University Students Association. Aware of Graeme’s talents, Knox engaged Graeme for the final part of his sentence to assist with Summer 79: a programme of public entertainment in parks around the Capital, conceived by Rohesia Hamilton Metcalfe of the Wellington City Council’s Parks and Recreation Department. An innovative feature of Summer 79 was that a number of the performing artists were employed under the government’s Temporary Employment Programme (TEP), an idea Rohesia says was inspired by the Wellington-based Artists Co-op which was already making use of the scheme. Graeme would add a number of live bands to the Summer 79 roster, including Rough Justice, the current lineup of his old friend and former cellmate Rick Bryant.

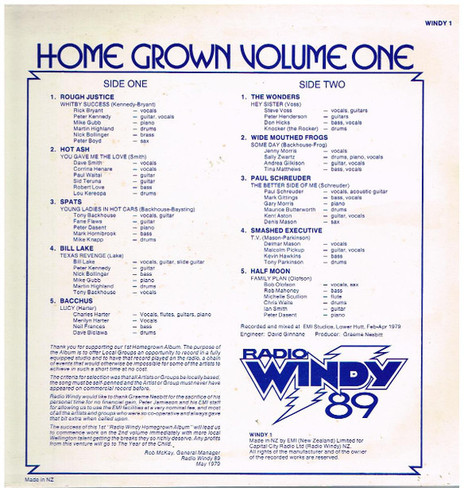

Rough Justice was just one of a number of local acts involved in another of Graeme’s post-prison projects. He had successfully pitched the idea to Wellington commercial station Radio Windy of sponsoring a promotional album of local music. The LP Home Grown Volume 1 appeared before the year’s end, with tracks by Spats, Wide Mouthed Frogs, Bill Lake and The Wonders, among others, produced by Graeme Nesbitt and heavily branded with the Radio Windy emblem.

Graeme thinking about rising unemployment and the place of artists in the community

Meanwhile Summer 79 had been a massive success, due in large part to Rohesia Hamilton Metcalfe’s creative use of the TEP scheme. This got Graeme thinking about rising unemployment and the place of artists in the community. As he explained to Fantl: “It became fairly obvious to me that these Labour Department employment schemes were going a long way to not only helping unemployment but adjusting society to the leisure age where people were going too have to creatively use their recreation time. We wanted to encourage unemployed musicians, actors, singers, writers, and have them perform some meaningful task in society.”

The following year Summer 79 morphed into Summer City with Graeme at the helm. The city council made available an historic two-storey house at 335 Willis St as its headquarters. Photographers, puppeteers, writers and musicians came on board, employed under the TEP scheme. These included former Mammal and future Crocodile Tony Backhouse, Wide Mouthed Frogs members Tina Matthews, Sally Zwartz and Katie Brockie, and music journalist Malcolm McSporran.

In 1980 Graeme received an Arts Council grant to travel overseas, looking at similar employment programmes that could be adapted to the needs of artists and sports people in New Zealand. He returned on Christmas Eve, “hot and excited with new ideas,” only to find that the Community Arts Council, under which he was employed, had made other plans in his absence. Suddenly Graeme was out of a job, “which was quite strange after whipping around the world giving and gathering information on unemployment programmes.”

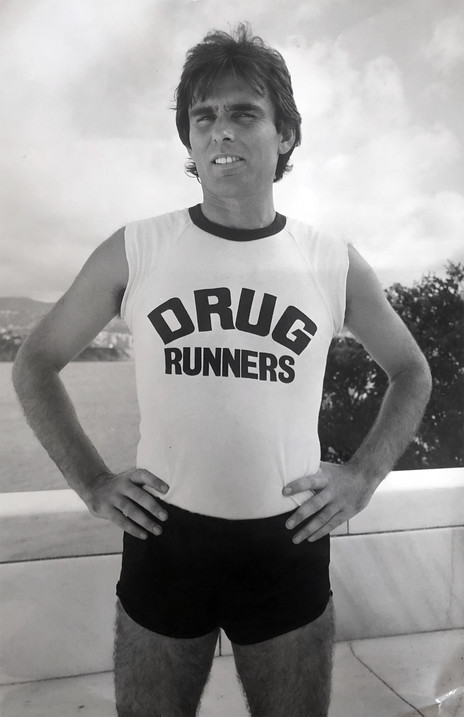

To keep occupied he took up running. He would sometimes run a hundred kilometres in a week, frequently jogging the thirty kilometres from his flat in Northland to his parents’ place in Upper Hutt to join the family for a Sunday roast. He formed a track team with a group of fellow former inmates and reformed druggies: The Drug Runners.

Returning to the rock’n’roll coalface, he started booking local touring bands into Wellington venues such as the Terminus Tavern, and took contract work as a tour manager for other promoters – Stewart Macpherson, Ian Magan, Chris Cole – which meant travelling the country with overseas acts: The Clash, Elvis Costello, Motorhead, Devo, Joni Mitchell, The Hollies. His local knowledge was welcomed by visiting musicians. He was able to explain the meaning of Waitangi Day and recommend the best New Zealand novelists and poets to Joe Strummer. He found Japanese restaurants and Evian water for Devo.

Occasionally his interactions with the internationals took a comic turn. When Talking Heads arrived in Christchurch for Sweetwaters South, Graeme was on hand to help, but their brash American tour manager told him his services wouldn’t be needed so Graeme stood aside while luggage and musicians were loaded into the tour bus. After the bus had gone, Graeme went into a nearby shop to buy a newspaper, where he was approached by a lost and confused-looking David Byrne, who asked: “H-h-have you seen my band?”

He also played a crucial role in reviving the New Zealand Music Awards. Run by a combination of industry organisations and sponsors, the annual event had enjoyed a high profile in the 60s as the Loxene Golden Disc, often with a live televised ceremony. But by the 80s it had dwindled to what Tony Chance, then Chief Executive Officer of the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand (RIANZ) recalls as “a glorified piss-up in a suburban hotel”.

“The 1982 awards had been an abysmal failure,” says Chance. “I went to a board meeting of RIANZ and told them the feedback I was getting from the industry. They thought it might be a good idea if I organised it for 1983, but I realised I’d need help so I called Stewart Macpherson. Stewart was busy but Graeme Nesbitt turned up in my office and said Stewart had asked him to fill in.”

Tony Chance of RIANZ quickly realised that Graeme had “a skillset beyond comprehension”

Chance quickly realised that Graeme had “a skillset beyond comprehension. He was the proverbial fixer. He could deal with egos – bring people down from angry heights, provide solace for them, while getting them to do exactly what he wanted them to.”

Dividing the tasks between them – Chance liaising with the industry and Graeme doing virtually everything else – they mounted a ceremony in the Michael Fowler Centre that would be broadcast live on national television and watched by 800,000 viewers. Graeme promoted and stage-managed the event, which despite all the industry freebees delivered a healthy box-office profit.

After the resounding success of the 1983 awards, Graeme returned to fill the same role for the next two years and continued to manage the event once it returned to Auckland in 1986. His ongoing work with New Zealand bands included taking Wellington chart-toppers the Holidaymakers to Fukuoka, Japan in 1989 for the Asian and Pacific Music Festival. But there were extramusical roles too: tour managing an All Blacks supporters trip to Australia, and – much to his amusement – the New Zealand visit of Pope John Paul II.

Graeme’s youngest brother Bruce once asked him why he didn’t become a promoter himself, rather than always working for other agents. Graeme explained that it would immediately put him in competition with all the people he currently considered his allies. He preferred cooperation to competition.

Through the 80s he also took on promotions contracts with commercial radio stations, first Radio Windy and later 2ZB. Although he maintained his usual dynamic pace, friends began to notice his growing dependence on alcohol. Some, such as Jim Stevenson, traced the beginnings of his drinking to his time in prison, which he saw as ruinous.

In the 1990s Graeme went to live in Asia, in part to escape the booze. From 1992 to 1996 he worked in Singapore as marketing consultant and tour manager at Frontier Touring and Cole Productions. In 1996 he moved to Malaysia. Living in Kuala Lumpur he resumed his academic career and taught media studies, as well as becoming the Malaysia correspondent for Billboard magazine. He converted to Islam, taking the Muslim name Muhammad Ilham Nasir bin Abdullah, and married Sharifah Nur Anthasha, a presenter for Malaysia state television. Peripatetic friends such as Tony Chance would stop by to visit on their travels. Others, like Rick Bryant, kept in touch by long distance call. The last time they spoke was in 2000, after Graeme had been diagnosed with cancer. As I recounted in my book Goneville:

They reminisced about high times and fallen comrades, but Graeme soon sounded tired.

“I don’t know what to say,” Rick admitted.

“Why don’t you sing to me?” Graeme said.

Rick sang him a blues.

Graeme died a month later, in June 2000. He was 49.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air