Much of Magan’s career path was informed by his passion for music. He grew up on a farm in Orini, near Hamilton, and his love of music and radio came about through listening to the 1ZB request session. Magan developed a love for guitar music, but adds that he has been “lucky to appreciate music that just ‘gets’ you and it’s not through superior education or anything like that. It’s just a range of experiences listening to radio as a kid all the time … no television … just exposed to a very wide range of music including classical music, folk, jazz, blues, you name it.”

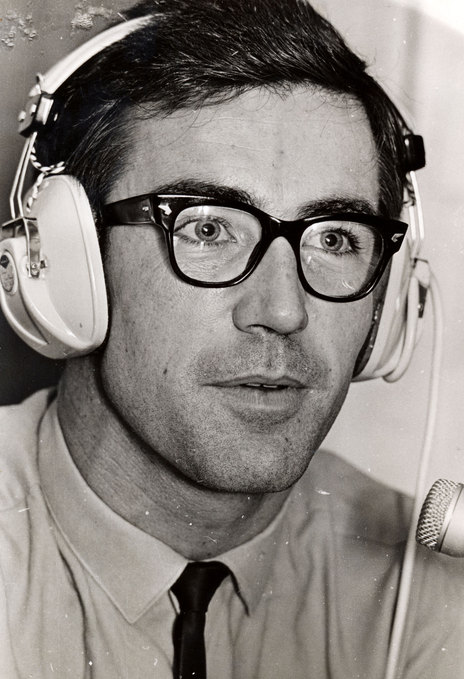

Magan was offered a job in 1962 working for a NZBC radio station in Whanganui. He agrees that this was a position that determined much of the man he has become because it lead “inevitably to getting into the live entertainment business”.

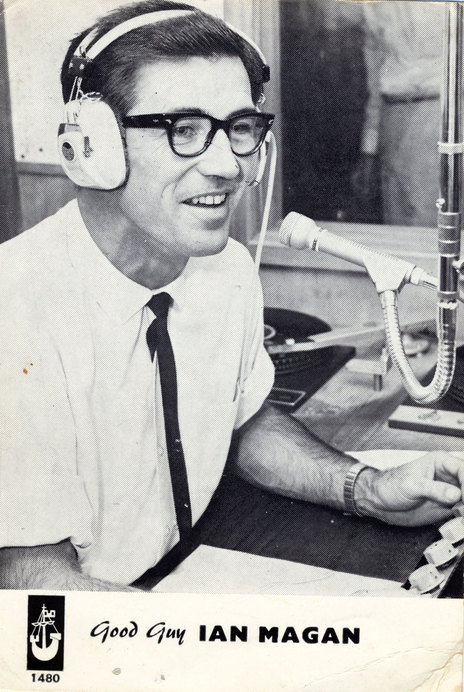

Working in radio was always his ambition. “I can remember getting my first pay packet and thinking, ‘Why are they paying me this much for something I always wanted to do?’”

Magan had four happy years learning the radio business with the NZBC in Whanganui, but in May 1966 – when the opportunity came up to join the founders of Radio Hauraki – he “couldn’t resist it, and I went for it boots and all”.

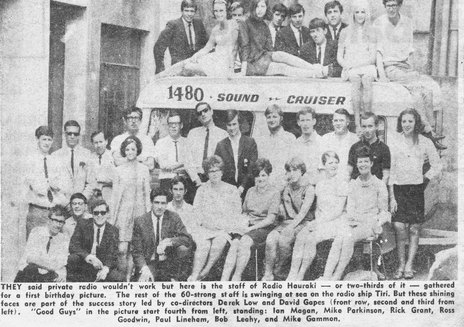

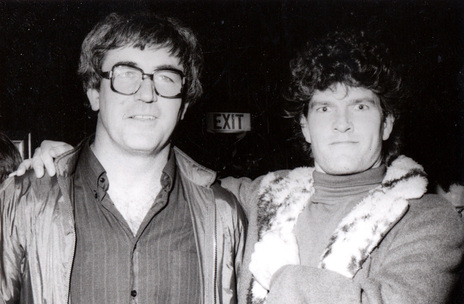

He joined the original team of “Good Guys”, the DJs that started pirate radio, broadcasting from the MV Tiri, a boat in the Hauraki Gulf, outside New Zealand’s waters. Radio Hauraki’s well-documented story began with two men, David Gapes and Derek Lowe (father of Zane). Together Gapes and Lowe literally took the “system” on and spearheaded the birth of commercial radio in New Zealand.

As David Gapes wrote in an interview I curated for NZ Musician in 2006, before Radio Hauraki “there was a radio wasteland made up of horse races, rugby, Aunt Daisy, Doctor Paul and not a lot else. Radio, in short, was bloody awful. All plummy non-Kiwi accents, horrible ads and no music.”

When the news broke about the planned station, Gapes and Lowe were immediately contacted by frustrated employees of the NZBC. “One of these was Whanganui-based announcer Ian Magan, who didn’t even phone,” Gapes recalled. “He just hopped in his Vauxhall Velox and drove to Auckland where we immediately signed him up.”

There were many, many battles in front of the pioneers of Hauraki: political, technical, financial. But the “Good Guys” were dedicated, and the station quickly developed its own sound, a brand, and an ever-growing audience. Among them were a few teenagers belonging to the politicians, says Magan, laughing. “I’ve still got this photo of Muldoon on holiday at Hadfield’s Beach and his kids are wearing Hauraki tee shirts.”

Signing on to work at Radio Hauraki was quite a courageous move.

In retrospect, signing on to work at Radio Hauraki was quite a courageous move given the Good Guys were being paid a minimal income and were also on the wrong side of the law.

Did Magan consider those factors when he was proposed the job? “Oh very much. I think it probably went through my parents’ minds more than went it through mine. I was unmarried at the time. I was in my early 20s and I think my parents were petrified at the thought of me breaking the law … and me making a bloody idiot of myself, y’know. But when you’re young like that you’re bullet proof: you don’t think about the consequences that much. Our passion for the cause far outweighed any fears we might have of repercussions. You had to be passionate about the cause, which was telling the Government to get its bloody hands off broadcasting.”

Being out at sea was pretty rough. Magan claims he “didn’t have it so rough because I was on air. We discovered quite early on that announcers couldn’t really work on the boat because you couldn’t play records. The ship was rocking all over the place and there wasn’t enough room on the boat to carry a whole team of people, unlike the British pirate ships, which were big ships and more stable. So we worked up a system of pre-recording our programs half-hour by half-hour exactly a week ahead on tape and those tapes were flown out once a week and then they had live links in the half-hourly tape change-over times. We had two guys on board doing those links. They were the real heroes ’cos it was a bloody awful life out there. It was cold, wet and they had no money.”

Magan told the NZ Herald in 2014 that when Radio Hauraki first took to the high seas, “most of us were optimists and thought we’d clean it up in six-to-eight months. Instead we spent three-and-a-half years having no idea of what the next day would bring.”

He said that those involved in Radio Hauraki at the time were conscious “of our place in history, because every thing we did got reported and blown up, y’know … we were the focus of some attention, particularly David Gapes and Derek Lowe who played an incredible political game, getting close to politicians … nobody knew a thing about the background goings-on. Getting close to the very people who we knew could bury us in 24 hours. Those guys [Gapes and Lowe] worked away at those people from the Prime Minister down. We made some very close associations there and nobody, the press included, had a clue what was going on. That kept us afloat in a major way, having the right attitude with the politicians and proving to them that we weren’t out to bury politicians. We were out to bury Government control of radio. Two different things, and I think Gapes and Lowe in particular made the politicians see that.”

Magan also acknowledges the crucial role Lowe and Gapes played keeping the crew together during that uncertain time, while helping their crew maintain a motivation in their mutual belief. “David just lived and dreamed it and only had to say, ‘I want to do this, are you interested?’ and we put our hands up straight away, not just because we wanted to do it but because we admired his capability and charisma.”

“Dad kept saying the old thing about when are you going to get a real job.”

Did his parents sanction his career choice? “God no ... I came from a wonderful but conservative Waikato family. My father never quite got used to it. My mother gave up after a while but my Dad kept saying the old thing about when are you going to get a real job.”

Radio Hauraki changed the face of New Zealand popular culture and of course radio. They learned the power of building a fan base and worked closely with a growing local live music scene.

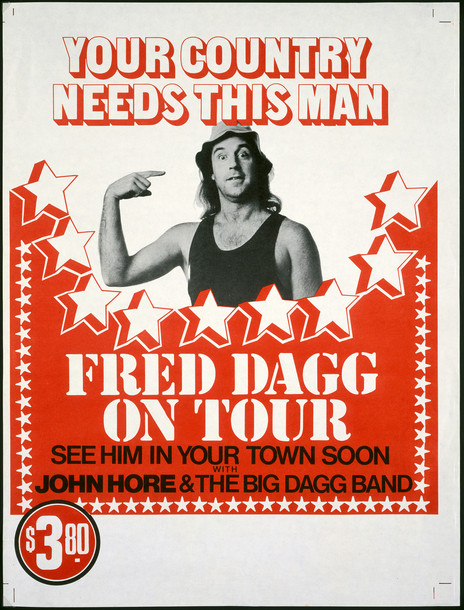

Hauraki was active in putting on live shows and Magan was heavily involved, working and staging shows with artists as diverse as Larry’s Rebels, Split Enz and Fred Dagg, often for charitable causes. And soon, overseas touring companies were knocking at their door.

Magan: “I had worked with Benny Levin, Phil Warren and other local promoters and I’d also been doing work with a crowd called Concerts West out of Dallas in the USA. In fact, with our help, when I was at Radio Hauraki, they put on what I would call the first of the modern-time outdoor shows, as we understand them today: that was for Creedence Clearwater Revival in 1972 at Western Springs. We played without a roof and on a stage made out of 44-gallon drums and wooden pallets – you wouldn’t be able to do that today – and when it rained they all got wet and kept playing. It was $3.80 a ticket.”

The station’s growing influence, branding and audience loyalty gave Radio Hauraki the ability to break records, often before the local label distributor was aware of the act or had a grasp of their commercial potential.

Magan had been instrumental in establishing a commercial platform for Creedence Clearwater Revival in New Zealand. While in Australia in 1969 he was given the 7" single of ‘Proud Mary’ and took it back to Auckland.

“A disc jockey at [Sydney’s] 2SM slipped it to me and I brought it back after my honeymoon and we played it [on Radio Hauraki] and we loved it. We rang Festival Records and said, ‘Hey, we’ve got “Proud Mary” and we want to play it’ but they said ‘well we’re not going to release that band. We don’t think they’ve got any future.’ [Magan laughs] So we said ‘bugger you, we’ll play it every hour on the hour’ … and of course it became this enormous hit!”

Within a month Festival Records rush-released the single into the market. The Concerts West organisation didn’t have a local agent “so by de facto we [Hauraki] were involved in the pioneering of the big concert market. Our next big concert was with Three Dog Night.”

Concert promotion requires a special breed of person and Magan has demonstrated he is of that stock. He has promoted a diverse number of shows that range from Tony Bennett to Pavarotti, Norah Jones to Vanessa Mae, Ray Charles to Elton John, BB King to Dire Straits.

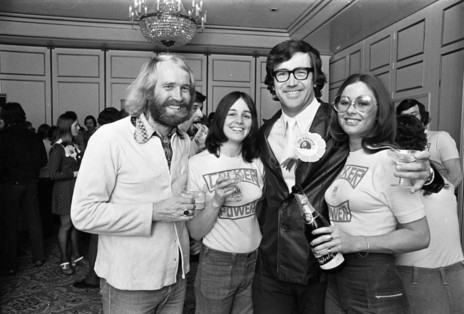

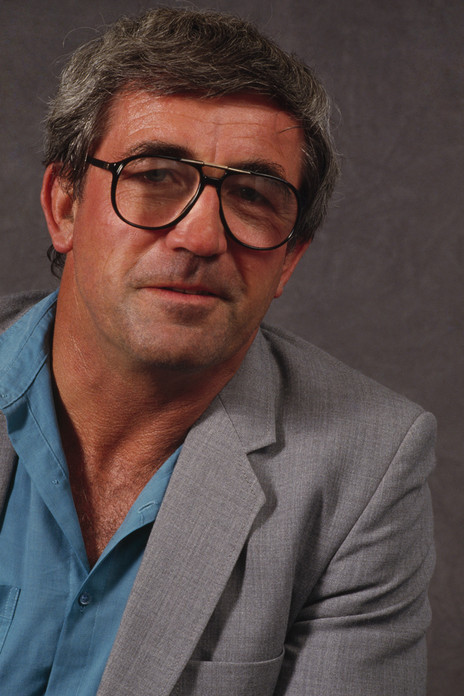

Building on the contacts made from his high-profile days in radio, Magan went on to form the Concert Promotion Company in 1975, later merging with Gray Bartlett and Pacific Entertainment in 1995.

Magan’s career in staging and promoting large international and local shows has been both “diverse and demanding” but nonetheless, it is work that he clearly loved. He describes his role in putting on large concerts as being something of a “one stop shop”.

“A lot of companies use different agencies and sub contract their work through different agencies,” he explains. “We tend to do most of that work ourselves. We book the air travel ourselves, we book hotels ourselves, the transport – we tend to contract out technical services like sound and lights ’cos that’s very highly specialised work, but we co-ordinate the whole tour including advertising. For promotion we hire publicists to spread the word although we control all our artwork, make our own radio ads and TV commercials.”

Radio Hauraki “was fiercely on the side of promoting local musicians.”

Back in the mid 1960s, local touring was still coming of age. “We would probably have to credit Peter Sinclair in those early television programs like C’mon and other shows that got the local acts being seen at peak time, so obviously local touring was spinning off that. Ray Columbus would do a tour, Larry’s Rebels and all those big bands, who were big because of the C’mon programme – and made even bigger, I might add, because of the support that Radio Hauraki was giving them. We were fiercely on the side of promoting local musicians – so there was a good touring culture developing and people like Benny Levin, Russell Clark and many others were exploiting all of this by the time I got into the business.”

An active pub circuit was also beginning to flourish (this was a time before strict drink-driving laws). “In those days you could go to the pub, as we did, for two hours every night and drive home happily. Obviously that encouraged the big barns like the big pub called the Thunderbird Valley Inn in Glenfield which held around 1800 people so you’d jam them in there – bands like Tommy Adderley and The Chicks – and have a bloody good night.”

Magan decided to specialise in larger concert theatrical acts rather than working pubs, which soon dried up after drink-driving laws were tightly enforced. His work as a radio “Good Guy” and helping organise live shows on behalf of Radio Hauraki proved to be his entry point into live concert promotion: free concerts in Albert Park – with Split Enz and others – and the legendary Buck-a-Head concerts. These were usually run purely for promotion and were lucky to break even, but as a promotional tool they served to establish Radio Hauraki as a committed supporter of New Zealand music and musicians. It was important to the station that it kept cementing a reputation of giving local music a platform. This was a massive point of difference that appealed to the baby boomer, pop culture generation.

Larry Morris gives Radio Hauraki the credit for Larry’s Rebels’ first No.1 single with the song ‘It’s Not True’ (written by Pete Townshend of The Who).

Larry Morris gives Radio Hauraki the credit for Larry’s Rebels’ first No.1 hit.

Speaking to RNZ in 2017, Morris said: “David Gapes, God bless him, I’ve got a lot of time for David and Ian Magan, Derek Lowe and all those guys who were there at Hauraki and believed in what they wanted to do. They were never going to give up, and we [Larry’s Rebels] could help them … so David and I were talking and he said ‘I’ll tell you what Larry, we’re going to get our licence eventually. There’s so much force behind us with the kids and everyone realising that we need to be given this licence and we’re not going to go away. We’ll get our licence, but we need food for the Tiri – let’s have a concert in Albert Park. We’ll charge the kids no entry to get in but they’ve got to bring a can of food, whether it’s a small can or a large can or whatever. And you give us the food and I guarantee you that Radio Hauraki will give Larry’s Rebels their first No.1 local record. We shook hands and I said, you’ve got a deal. We got a ton of food, I mean we filled up three trucks with food. We had 2500 people in Albert Park. They all brought cans of food. We had so much food. One of the trucks took the excess they couldn’t get in to the hold of the Tiri and took it to the City Mission. I remember this like it was yesterday. David was a man of his word.”

When Magan decided to get out of radio in 1976 he moved into concert promotion. His first act was Fred Dagg: the alter ego of John Clarke. “John was ready to tour, he’d had enough of TVNZ, they were treating him very badly and he wanted to go to Australia to live and he needed a grub stake. So we did this huge tour, a fantastic tour, and very successful …we kept going around [New Zealand] all the time ’cos it kept selling out. He was so popular.”

From that friendship Magan was able to build other relationships, he says. “We were lucky enough to find acts that said, ‘We don’t want to play the pubs. We’ve got a special thing to tell and show people, we want to play theatres’. And that, of course, was Split Enz, and I got in right at the ground floor with Split Enz and had a wonderful 10 years with them, and later Crowded House.”

While working at Hauraki, Magan and his fellow broadcasters got to know and love Split Enz despite many in the industry not being able to see their potential and vision. “I always thought the whole band just had this international feel about music,” he says. “They were way ahead. They had the image but behind it all was the songwriting and brilliant musicianship. They created their own package and they took no notice of what other people did. They said, we’ll do it our way and stuff ya.”

Magan credits David Gapes – who later went on to manage Hello Sailor, including their ill-fated sojourn in Los Angeles – for instituting the famous Buck-a-Head Concerts. Split Enz was hired to perform, they charged punters $1 each to see them on a Sunday night, and obviously those concerts sold out every time. It helped Split Enz consolidate their growing reputation and repertoire and it certainly paid dividends for Hauraki. It was a cultural oasis out there and Hauraki had tapped into a musically hungry youth market.

“It was a cultural oasis out there.”

Magan: “There were two people [in Split Enz] who stood out and would sacrifice everything for their music, and who were absolutely bullet proof – and that was Tim [Finn] to start with … and then there was young Neil.They showed great leadership and enormous stickability during those years in England when they were almost literally starving. The whole band was. And of course they always had Eddie Rayner, a fine and inventive musician. You’d look a long way to find people like that, even today.”

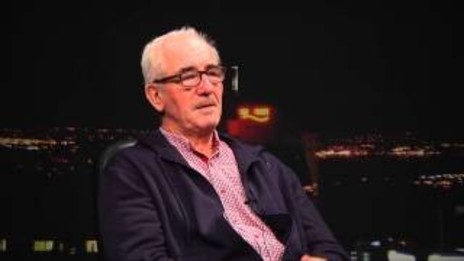

His experience was rooted in the belief that the effect an artist has on an audience is the most valuable currency there is.

Ian Magan died August 2019. His vitality and passion for the business kept him involved in music as a mentor and advisor well into what most people would consider to be retirement age, and his love for music endured right until the end.