AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

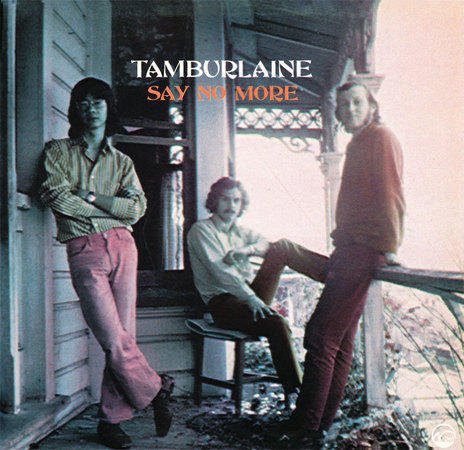

Tamburlaine

Raised in Wellington’s rich musical underground, the great Tamburlaine was born from British-style blues and the folk revival, and graduated from shouty, sweaty clubs to spellbinding larger concerts.

Guitarist Steve Robinson grew up in Fiji, where he studied piano from age four, played the violin in school orchestras and learned the ukulele, which naturally led to guitar. Returning with his family to New Zealand as a young teenager, he first played bass in Christ College’s ironically named beat covers band The Pagans, and later, lead guitar with Wellington College’s Us Five.

Long before graduating to guitar, young Denis Leong studied piano for eight excruciating years, while also developing his singing voice. Backed by brother Kevin on guitar, Leong sang and together the brothers dominated 1950s talent shows, where they regularly won prizes in competition and accumulated a modest collection of toasters and other small kitchen appliances.

“I would like to say we sang early Chuck Berry or Everly Brothers tunes,” says Denis Leong, “but … our repertoire was limited to all but the cheesiest of top twenty hits.”

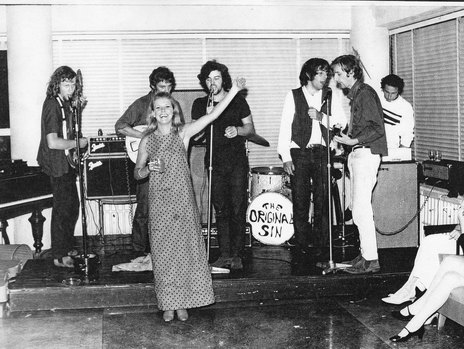

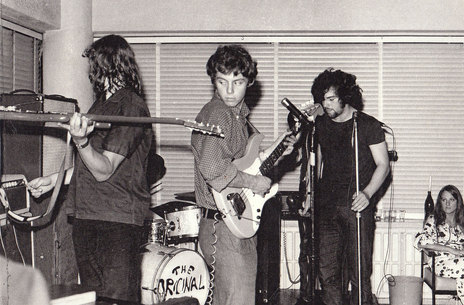

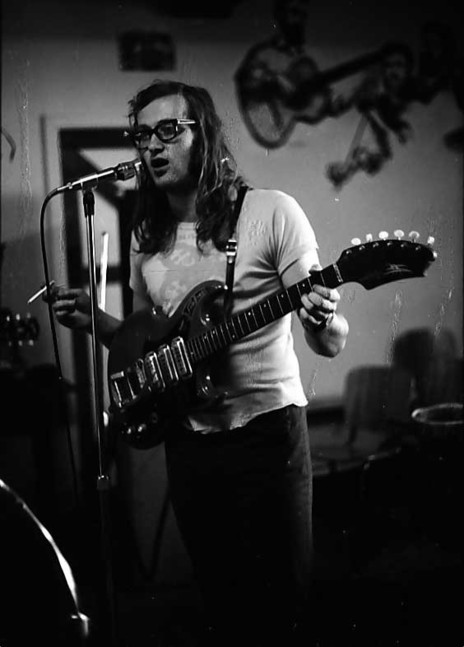

Meanwhile, bassist Simon Morris was playing lead guitar in his Onslow College school band Changing Times when formidable future vocalist Rick Bryant tried out for singer, but was turned down. Meeting up again with Morris at university, a newly honed Bryant fancied starting a “serious blues band”, and he and Morris bore Original Sin. “Original Sin was very much a bunch of mates into Chicago type blues (Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, etc.), pretty much driven by Rick," says Steve Robinson.

After unshackling from Rick’s harmonically-challenged brother Rod on mouth harp, the Sin really caught fire when ex-Canberran draft-dodger Bill Lake took on guitar and harmonica. Cafe L’Affare founder Jeff Kennedy played drums, rounded off, says Morris, with “a revolving door of bass-players. We could never hold onto one. Steve Robinson was one, Tony Backhouse another, [and] Lindsay Field [later an in-demand backing vocalist in Australia]."

“I went to see Original Sin perform in a school gym,” says Denis Leong. “The stage was full but the hall was empty and there was possibly just one functional amplifier. I was there because Rodney Bryant – a year younger at Rongotai College – claimed to play in a rock band. A group of fellow sixth-form skeptics went to check this out. While Rodney did not play, his older brother Rick did, ably fashioning a credible Chicago blues frontman persona in the manner of a prematurely weathered Van Morrison. More striking was another fellow who did all the talking bits between songs. This fellow told great jokes and projected a very sunny entertaining disposition … a touch at odds with the otherwise grim authentic blues ethos. That was Simon.”

Sure, Original Sin had started off playing “authentic” blues – via the Stones and The Pretty Things – but soon the Sin stepped even farther from the source when Hendrix and Cream modified the mix. Songs got longer, tempos and keys changed more, and there was more adlibbing and improvisation.

They played sporadically – including a gig for the Karori Girl Guides – and by 1968 they were the resident band at the Mystic, on Wellington’s Willis Street, a hot, smoky blues club with ultraviolet lighting.

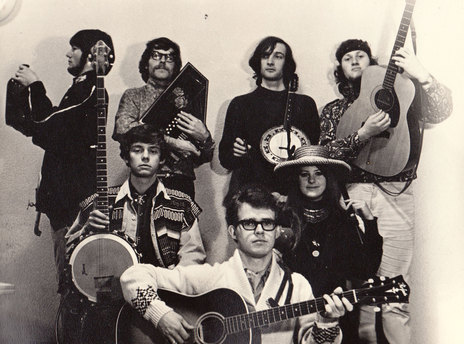

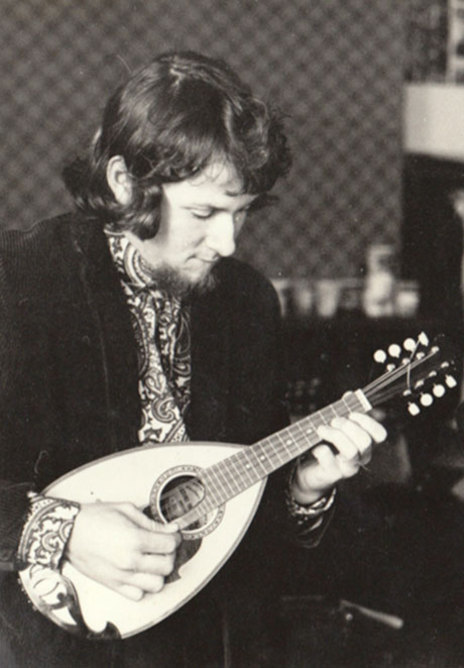

Tamburlaine was renowned for their rich vocal harmonies and diverse instruments.

Perhaps as penance for the volume and excess of Original Sin, Morris joined a jug band with fellow student Lindy Mason – the Kelburn International Airport Ceremonial Guard Band – which also featured her boyfriend and ex-bassist Steve Robinson, with Mitch Park, Mike Rashbrooke on the jug, and future Windy City Strugglers Bill Lake and Geoff Rashbrooke. Mason introduced the KIACGB to West Coast American bands Jefferson Airplane and Buffalo Springfield, and the group started to introduce techniques which would become Tamburlaine standard practice: rich vocal harmonies and multi-instrumentalism. Morris took on traditional – if somewhat silly – folk instruments like tin whistle, ukulele and kazoo, with Robinson on guitar and high harmonies. The group played the Christchurch Arts Festival in August 1967.

“The fact is, we loved singing together. Harmony vocals have been my favourite thing in bands,” says Morris.

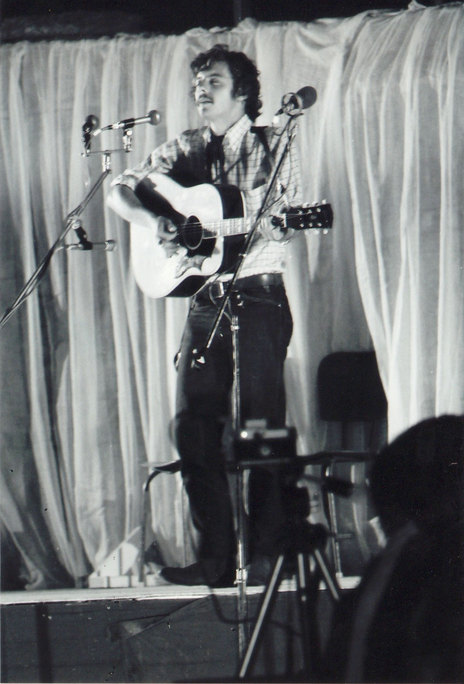

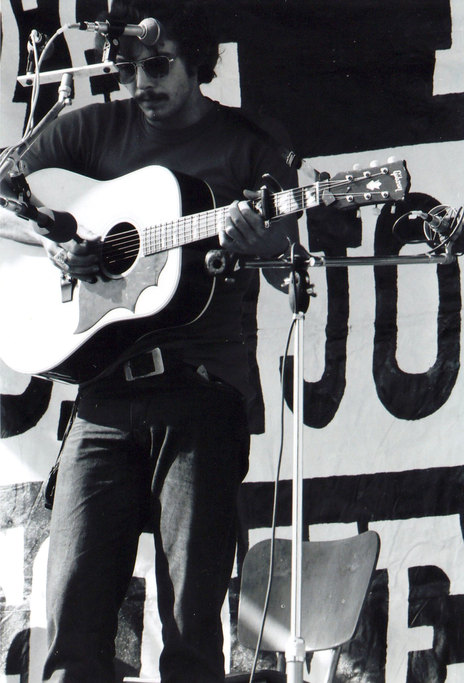

After his two-month stint in the Sin (“I think he objected to working four hours a night for no money, or something!” says Morris) Robinson went exclusively folk. Studying sociology and anthropology at Vic, his tastes had changed from high school beat bands through the blues to Dylan, The Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary. He joined Victoria’s folk club during Orientation, and later became President with Lindy Mason as Secretary.

Wellington’s coffee house/ folk club scene was merrily percolating away, and Robinson played several times a week at these new venues: The Chez Paree at the Embassy Theatre on Courtenay Place, the Balladeer, and particularly the Monde Marie in a duo with Mitch Park, where the fee for playing was “$2 an hour plus a bowl of Hungarian goulash.”

The Original Sin’s residency had shifted from the reasonably scuzzy Mystic to the post-apocalyptic, student flat-like Mystic II, and they split up in 1969 when the academic year finished.

“Bill Lake, Tony Backhouse and I decided to form a group specialising in hard songs we could barely play,” says Morris. “Frank Zappa, Spooky Tooth, Jack Bruce – and finally a few originals.”

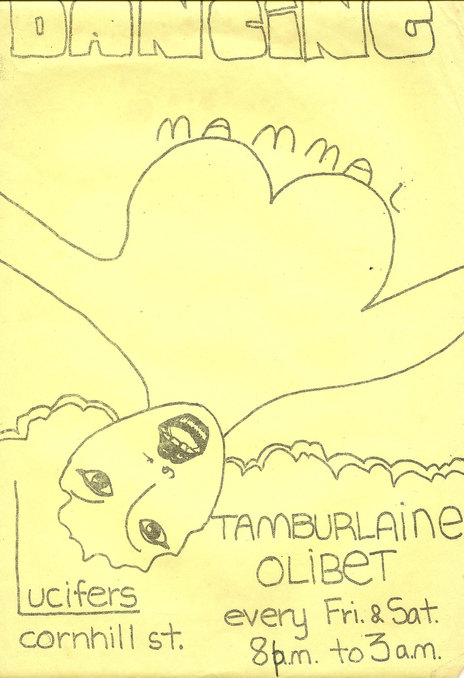

This first incarnation of the band is often referred to as Simon and the Mammals, but the band was just called Mammal, says Morris.

Mate Mark Hansen had a fab pad in Lyall Bay for band practice, and he signed up as their (unexpectedly short-term) drummer. Sin singer Bryant had gone on to get Gutbucket going after Original Sin, but soon joined the flocking Mammals, swapping in Gutbucket’s drummer Mike Fullerton for Hansen.

“After a while the Original Sin, and later Mammal, were quite keen on generally showing off,” says Morris. “Since none of us were exactly virtuosi, our showing off was more about keeping the audience on its toes – lots of unexpected vocal backup bits, quotes from well-known songs in the solos, that sort of thing. And in 1967, suddenly a lot of other bands overseas started doing the same thing – The Beatles of course, the Stones, then Incredible String Band, Moody Blues. I think all we wanted to do was make something a bit interesting.”

And if that wasn't interesting enough, Geoff Murphy invited the irrepressible Morris to play bass with him and Bruno Lawrence in their project The Acme Sausage Company, soon to become BLERTA. “They wanted a bass player. Could I play bass? The correct answer to this question is always ‘yes’. And fortunately I managed to borrow, and later buy, Tony Backhouse’s bass, a tiny Maton with an unbelievably narrow neck. Which meant it was incredibly easy to play. The sound of Tamburlaine – the bottom end at any rate – was entirely down to that.”

Tamburlaine the Great, Part I

Now studying Zoology at Victoria, Leong had a lovely low voice and a flash acoustic guitar, and was learning technique from Robinson. “Steve Robinson was an exalted leading light in these circles,” says Leong, “a highly accomplished blues picker and singer songwriter, with a broad repertoire that included a few mysterious old-time tunes, probably intricate elaborations on Fats Waller originals. I summoned up the courage to ask him for lessons and paid him for about a half dozen sessions.”

“I was playing a lot of songs that employed the technique of finger-picking called ‘clawhammer’,” says Robinson, “where the thumb alternates the bass line and the fingers counter the bass. David Calder (Hamilton County Bluegrass Band) taught me this technique. Denis asked me to teach him clawhammer. James Taylor, Simon & Garfunkel and Crosby Stills & Nash were perfect exercises for finger-picking."

“They were both very good at that smart, finger-picking style of acoustic guitar playing that I envied beyond belief," adds Morris, "my guitar style (electric) was cranking it up and grabbing long, wailing notes over the top.”

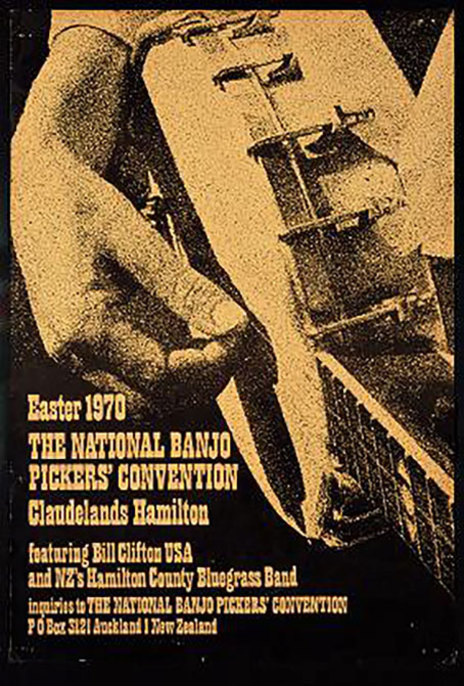

The two pickers polished their string work at Hamilton’s annual National Banjo Pickers’ Conventions, where both Robinson and Leong featured as soloists.

“Steve … unexpectedly agreed to teach me ‘Song for Sunday’, an original gem featuring some beautiful guitar work in open tuning,” says Leong. “I played that song at Banjo Pickers and the response to my very first solo performance was a huge surprise. The applause would not stop and when a slightly bewildered Mike Seeger (the international invited guest) brushed by to take the stage after me, he must have wondered what the hell was going on.”

Leong and Robinson were keen to start a group that would play the exciting new sounds in the folk tradition.

Leong and Robinson were keen to start a group that would play the exciting new sounds in the folk tradition, now called “singer-songwriter”, and needed some bass to round out the sound. (“Since I owned one … of course I said yes,” says Morris.)

But first they needed a name. "Honestly, we agonised for months. Simon added more pressure with the flippant if not anomalous 'The Joy Boys'," jokes Leong.

Both Morris and Mason (daughter of playwright Bruce Mason), were studying Medieval Literature at Victoria University, where one of their course subjects was Tamburlaine the Great by Christopher Marlowe, a 16th Century play about a Tartar warrior.

“One afternoon," says Leong, "while browsing the bookshelves of Steve and Lindy’s student flat, I came across the classic Christopher Marlowe text and shouted ‘How about Tamburlaine?’ Steve approved from the next room but Simon had major reservations. Simon’s previous groups all enjoyed thoughtful, often sharp, forceful names. When pressed, Simon felt Tamburlaine was a bit ‘fay’. Push come to shove it was fay or gay, and so we became Tamburlaine.”

“The worst thing about forming a band is coming up with a name,” says Morris. “Generally, the least-bad one gets accepted gratefully. Tamburlaine sort of fit anyway – a bit arty, a bit rocky, a bit mythic.” “Seemed like a good hippie kind of name,” says Robinson.

A few short months later, and the band were already on record. Their first recordings (credited to The Tamburlain) were included on the National Banjo Pickers’ Convention 1970 LP, highlights from an Easter performance that year at Claudelands.

“Banjo Pickers were way ahead of the curve in encouraging a progressive and eclectic programme,” says Leong. “Tamburlaine was embraced expansively to broadcast that the festival was not just a stop for crapped-out liberal folkies enjoying the blue grass. The festival even arranged a session where Tamburlaine was interviewed (along with the Hamilton County Bluegrass Band) and a few hundred people showed up to be entertained by Simon in his element. As much fun as those interviews were, one of my enduring memories of Banjo Pickers is of Simon Morris that evening playing a broad selection from a new The Band album with pitch-perfect sensibility, on unadorned guitar. He held that little tent audience spellbound.”

On the record, Robinson does a faithful, slightly bluegrass (in the spirit of the day) solo guitar and vocal rendition of Lennon and McCartney’s ’The Ballad of Rocky Raccoon’. The two tracks from “The Tamburlain” – James Taylor’s ‘Something’s Wrong’ and Simon and Garfunkel’s ‘Only Living Boy in New York’ – have all the trademark Tamburlaine traits, albeit embryonically: dual finger-picking interplay, sweet three-part harmony, Morris’s bomping bass.

The recordings were produced by John Ruffell, who would work with Tamburlaine again on later projects, and featured flautist Penny Evison, who came up from Christchurch to play with the group. Years later she met up again with Morris, and the two have been together since.

In 1971 Tamburlaine was performing around Wellington with similarly progressive folkies at the university and Chez Paree. “I vividly remember coming off the stage in the Victoria University Union Hall March 1971," says Robinson, "and seeing the next band due to go on, heavily made up with mascara etc. It was the first line-up of Split Enz.”

By May they were in the studio, recording for Kiwi Records, who had set up a new Tamburlaine-focused sub-label: Tartar.

“We got signed up ridiculously easily by Tony Vercoe at Kiwi Records,” says Simon Morris. “He was a lovely old chap, and he promised us not only an album contract – recorded at a real studio, EMI, with a real producer, Alan Galbraith – but our own label, you know, like Apple. And the spirit of The Beatles was all over the first album – even the title Say No More was a running gag in the movie Help. We’d write a song, arrange it, then embellish it with overdubs. Alan Galbraith made sure it didn’t get out of hand – with one exception – and it was a lot of fun.

"We didn’t have a drummer at that stage, so Steve, who was the best rhythmically, did a lot of percussion – tambourine, bongos, tabla, that sort of stuff. I had the best ear for solos, so I’d usually do those – acoustic guitar, rudimentary piano, organ at one stage, and a bit of electric guitar. And Denis wrote the most specific songs, and brought some mates in to play strings and flute on them.”

“We had made a demo tape mostly of original material and this was shopped around to the various recording companies,” says Leong. “I was pleasantly surprised to get a call back from Tony Vercoe … Tony was planning to retire that year and he felt like doing ‘something out of the box’ with a final completely unexpected blockbuster. He had a twinkle in his eye when he gave me the numbers: there would be $30,000 available to record an LP in the EMI studios. Roughly speaking the budget allowed thirty hours of recording time on a lovely four-track machine, the very model that The Beatles had used to record Rubber Soul. There had been many surprises over the previous twelve months but this was right up there. We signed, somewhat in disbelief.”

‘Say No More’ is simply astonishing, and rightly recognised as one of New Zealand’s 100 Essential Albums.

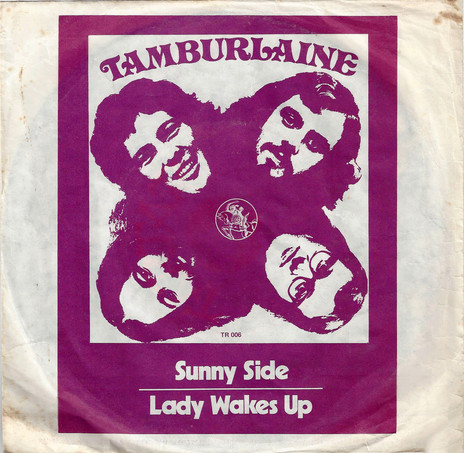

Say No More is simply astonishing, and rightly recognised in Nick Bollinger’s 100 Essential New Zealand Albums. Robinson won the 1972 APRA Silver Scroll for ‘Lady Wakes Up’ and for good reason: a simple, elegant arrangement with guitars, subtle flute, hand-claps and wood block grace the homely homily: “In your woodbox of memories, may I be a chip.” When Julie Needham’s fiddle comes in during the opening to ‘Raven And The Nightingale’, it briefly foreshadows Alastair Galbraith’s violin on The Rip’s ‘Starless Road’, 15 years into the future.

On a universities tour with rock poet Sam Hunt in 1973, Morris got a nod from the icon. “What I remember most though was Sam telling me how much he liked the words of 'Raven And The Nightingale'. Whoa! High cotton!”

Borrowing from his and Lindy’s English Lit studies, Morris reveals ‘Raven ...' to be “Pure Keats”. “ ‘Flame of Thoriman’ is Robert Browning, ‘Saffron Lady’ is – well, that’s Ravi Shankar.”

Tamburlaine had started – like most 1960s New Zealand bands – as a cover band, with lots of James Taylor and Simon and Garfunkel covers. "But it was 1970," says Morris, "and we decided we’d only record originals – and one Steve Stills number. Denis brought it in, and Steve and I refused to listen to the record. We’ll do it our way, we said. And we did.” On ‘Do For The Others’, Leong’s low, easy voice stands stark and soulful (as opposed to Stills’ slick double-tracked vocals) with Morris and Robinson on high harmonies.

Keeping it Beatles-y, ’Saffron Lady’ is Tamburlaine’s ‘Sexy Sadie’ – not another cryptic indictment of the Maharishi, rather an elliptical love song to the music of Ravi Shankar. Unlike Lennon’s plaintive scathing, the band bounces between faux-Eastern sections (hand drums and ringing, reverbed, arpeggiated minor chords), and good old Western folk guitar and harmony vocals.

“‘The Flame of Thoriman’ was learned in a white heat over about a week or so, and we played it live once – at a university concert featuring Tamburlaine, Mammal and a young singer called Rob Winch,” says Morris. To contemporary Peter Jackson-steeped NZ ears, it’s quite Tolkienesque, but there was a lot of that fantasy-British-iconography from bands at the time: ‘Frodo’ from Tamburlaine’s label-mates Tole Puddle, Led Zeppelin’s ‘Ramble On’, Pearls Before Swine’s ‘Ring Thing’, and pretty much everything from the Steve Peregrine Took-era Tyrannosaurus Rex. Aside from its imagery, ‘Thoriman’ has the complex structure of an intricate narrative, influenced perhaps by Morris’ favourites Moody Blues, with interludes of West Coast sunshine pop, UK heavy psych, and even some jangly Byrds guitar.

The songs sit tight with Fairport Convention and the Incredible String Band, with bits of Big Star and Buffalo Springfield too, but for all their Beatle-Byrds harmony vocals, Tamburlaine are most famously known as NZ’s answer to Crosby, Stills & Nash.

“Although Denis and I weren’t playing Crosby, Stills and Nash they became an important influence when we started Tamburlaine,” says Robinson. “Two of our CSN show stoppers were ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’ and ‘Carry On’. We nailed those two tunes. Simon was right into bands like The Moody Blues, basically anything with sophisticated harmonies. We had a great blend vocally with Simon in the middle, Denis down below, and me on top, and we backed that up with great acoustic guitar work from me and Denis, anchored by unfettered bass from Simon.”

Though blessed with these blissful vocal harmonies, Leong found fault in their production. “As a group we came together most in three-part harmony with each voice comfortable in its natural register. It was not so much the blend but more the fact that all three voices seemed able to attack with unusual aggression. Inexplicably, almost all of the vocal aggression was suppressed in the final mix in preference for a dominant lead voice. I have always thought the greatest strength of Tamburlaine was left off the record.”

On their next record, Tamburlaine would struggle with much more deeply troubled mixes.

To outsiders this difference was perhaps unnoticeable, but on their next record, Tamburlaine would struggle with much more deeply troubled mixes.

Following the release of Say No More, Tamburlaine explored their trad roots by catching up with some fellow Banjo Pickers in Hamilton and contributing three tracks to the Song of a Young Country double LP of New Zealand folk songs. From songs collected by folklorist Neil Colquhoun and again produced by John Ruffell, the album explored New Zealand’s historical folk traditions, drawing from nearly forgotten and well-documented historical songs, as well as contemporary interpretations. Among time-honoured techniques with Celtic inflections or English-style ballads from contemporary traditionalists like Marilyn Bennett and Phil Garland, Tamburlaine contributed three songs – in a style described in the liner notes as “almost ‘pop’ extensions” – over the four sides.

Morris says it was, “One of the most enjoyable recording sessions I've ever been on. One take, goodbye! The apparent overdubs were recorded at the same time – all played by legendary multi-instrumentalist Robbie Laven.”

Tamburlaine also dropped into the studio to record two more sides for Tartar, the two parenthesised Dylan tracks, ‘(Just Like) Tom Thumb’s Blues’ and ‘If You Gotta Go (Go Now)’, sung by Marilyn Bennett with Robbie Laven and Tamburlaine. Bennett’s voice is sweet and pure, soft and somewhere between fragile Vashti Bunyan and unaffected Shirley Collins, with Laven and Tamburlaine providing lovely understated backing with tambourine, undistorted electric guitar, bass, spare drums and hand claps.

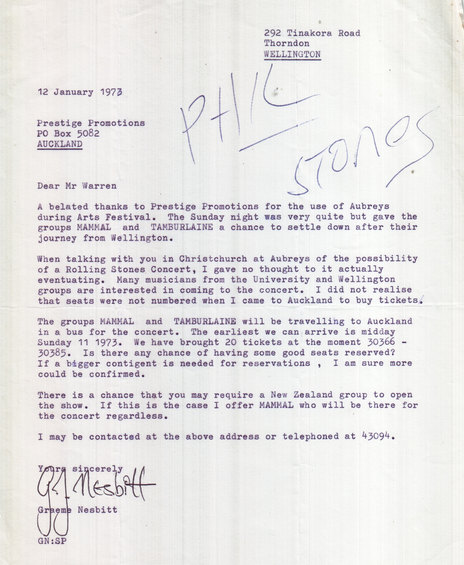

At this point, Morris was still playing with BLERTA (which had since evolved from Acme Sausage Company) and Mammal as well as Tamburlaine, “but since all our gigs were fairly sporadic, to say nothing of my final year at university, they didn't clash too much” when Tamburlaine were headhunted by media personality Brian Edwards to join a tour with The Rumour. “On the strength of that, I decided to quit Mammal and BLERTA and concentrate on Tamburlaine. Which was fine, except the Big Tour was a disaster … and suddenly I was a full-time folk musician without any work.”

Tamburlaine the Great, Part II

Leong had had enough. "We were writing for a second album at this stage. I know this because we played 'Rebirth' with Denis in Christchurch,” says Morris.

“Denis had other fish to fry,” says Robinson. “He wanted to pursue a scientific career in a ‘proper job’.”

“I thoroughly enjoyed the three or so undergraduate years devoted to Tamburlaine but all too inevitably came to a crossroads. I chose academia,” says Leong. He left the band to study and work, and in 1980 joined the faculty of the University of Virginia School of Medicine in the Appalachian foothill town of Charlottesville, Virginia, where he has lived ever since.

Tamburlaine found its feet quite quickly with new members Rob Winch and early Mammal drummer Mark Hansen.

Tamburlaine found its feet quite quickly with new members Rob Winch and early Mammal drummer Mark Hansen. “Mark Hansen was a drummer friend of Simon’s who had great charisma and taste in clothes, totally in keeping with the Incredible String Band/CSN image Tamburlaine was cultivating,” says Robinson. “He joined us playing congas, finger cymbals and triangles etc. It was all about the vocals with acoustic guitars, bass and percussion – not a drum kit.”

Hansen’s multi-instrumentalism was a natural fit. “We [can] get away with a bit more complexity than normal, but we don’t try to be intellectual,” Hansen told NZ Listener (16 October 1972). “We try to inject as much feeling into songs as possible, so that where someone may not understand lyrics we hope they groove on it in other ways.”

Another mate from the local scene, Winch took over on second guitar and rounded out their vocal harmonies. “I knew Rob when he came over from Nelson – a friend of various friends,” says Morris. “He could sing too … a number of us would get pissed at the Duke of Edinburgh hotel and launch into a cappella versions of well-known songs. He’d been in a little folk group with Sharon O’Neill, and clearly played guitar okay. So we invited him to join … and the vocal blend was even better than it had been before. We literally seemed to be able to sing anything together.”

Tamburlaine the second began to perform more extensively than before. “We had a variety of gigs at Vic and Polytech, especially with Mammal and The Windy City Strugglers,” recalls Robinson. “We toured Christchurch and Dunedin a couple of times. The Auckland Arts Festival was memorable in that we played on the main auditorium stage in a concert where Barry ‘soon to become Dame Edna’ Humphries was one of the headliners. [Humphries] sang three songs – including ‘Chunder in the Old Pacific Sea’. He then said, ‘Since my repertoire is essentially limited, I’ll now sing all three songs again and you can join in on the choruses.’ ”

Aside from occasional trips north or south, Tamburlaine mainly played in the Wellington region. In June and July 1972 they played the Lion Tavern in Molesworth Street, with BLERTA at The St James, and toured Masterton and Palmerston North with Mammal and Sam Hunt. At the end of July they played to a reported 4,000 punters at the Impulse 72 concert in Dunedin.

“I remember us running out on stage and launching into ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’,” says Robinson. “It wasn’t an original song but it blew everyone away.”

Morris recalls: “The Dunedin thing I think was essentially a Christian gig – hence the huge audience. Not sure why we and The Kal-Q-Lated Risk were there, but we both went down a treat.”

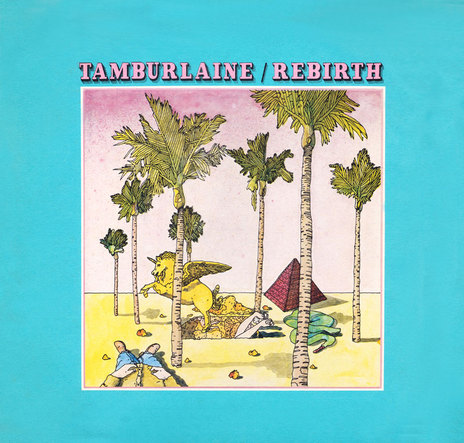

The new line-up had crystallised quickly, and after the heavy touring, they got down to recording a new album, christened Rebirth. Though recorded with the same engineer, in the same EMI studio as the first record, production whiz Alan Galbraith was unavailable and the band decided to produce it themselves. “It was a bit of a mess, until we invited Songs of a Young Country producer John Ruffell to step in and help,” says Morris. “Which he did, to the enormous benefit of the record.”

The band have always been unhappy with the production on this album – with the exception of Ruffell’s rescue work. Morris told NZ Listener, “The trouble with this album is that there have been so many new things to deal with. Rob and Mark are new, and we’re new as producers … Listening to the tape I now know a lot more about what to avoid.”

The reviews agreed. Kicking off with a compliment – “Their once folk-based sound is now more into country rock and it works far better for them” – Ray Columbus continues his review in a 1973 ‘Sound-Round’ column of the NZ Listener: “The LP lacks only one thing for me and that is the production, especially the remix ..." Though he readily offers technical support: “This can be adjusted easily though by turning bass controls back a little and treble up a touch.”

The album opens with ‘New World’, which for all their fears features some quite clever production: dual electric guitars duelling slightly out-of-phase or ping-ponging acoustics, and a foxy fake-fade at the finish. This track also introduces Winch the composer, and his further credit, ‘All In The Way’, fits right into Tamburlaine time, a Beatles-via-Steeleye Span stunner.

The rich, multi-layered vocals of ‘Maybe It’s True’ circle about before spiralling into a catchy, campfire-worthy sort of round, and Robinson’s second credit, ‘Love Song In G Minor’, is a simple, bittersweet, mandolin-soaked McCartney-esque gem.

‘Sleeper Awake’ is Morris at his complicated best. Hansen explains: “He likes to have to work on a song, he likes complexity, whereas Steve prefers simpler treatments.” (NZ Listener, 16 October 1972). Powering into it with Morris’ dancing bass line, the driving dual electric guitars and jazz high-hats give listeners heavy notice that Tamburlaine is indeed the prog conqueror, before dropping sharply off into achingly sweet vocals.

‘Take Your Time’ is perhaps the track that most fits the Crosby, Stills & Nash vocal mold. The album ends with ‘Rebirth’, an eco-epic on the same scale as ‘The Flame of Thoriman’.

From opener ‘New World’ to closer ‘Rebirth’, the album bursts with the youthful, hippie optimism.

“We started writing stuff that wasn’t so much actual songs, more lots of interesting bits strung together,” says Morris. “The longest song was ‘Rebirth’, and although it didn’t mean all that much lyrically, musically it was – in all modesty – a knockout. Particularly on stage.”

During the recording, Hansen described the album to the NZ Listener as “more rock, it has more punch. It’s more of a theme than a collection of odd things that individuals like.”

From opener ‘New World’ to closer ‘Rebirth’, the album bursts with the youthful, hippie optimism found on Shona Laing’s debut and common to Kiwi sunshine psych, whilst also recalling the Utopian aspects of Paul Kantner’s Jefferson Starship LP Blows Against the Empire.

Multi-faceted Auckland artist Denys Watkins designed the album, featuring his early trademark watercolour and pen-and-ink technique in the cover art. On the flipside, band photos show Morris, Hansen and Robinson decked out in Tamburlaine T-shirts, a logo in graphic monochrome of the band’s four faces radiating out below the grand name “Tamburlaine”.

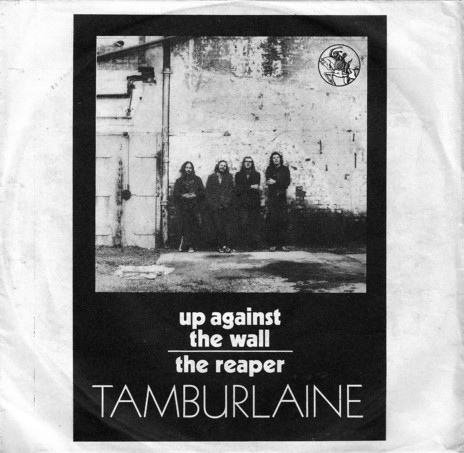

“After Rebirth we recorded one more single. Both songs worked well when performed live but the dynamics were never properly recorded on the vinyl,” says Robinson. Medievally-themed A-side ‘The Reaper’ sees the title character gathering corn for the mill as a death metaphor, while B-side ‘Up Against the Wall’ is driven by a conga rhythm in a 1970s, ethno-American protest vibe – with nods to Santana and Sly Stone.

Morris: “That [single] clearly could have used John Ruffel’s magic ears. Steve wrote ‘The Reaper', which was a bit half-baked in the arrangement. The perfectly good piano solo seemed to belong to a completely different song! And ‘Up Against The Wall’, which was a dynamite show-closer on stage, sounds extremely feeble on the B-side!”

Around this time Tamburlaine recorded incidental music and a few all-new, non-album tracks at Pacific Films in Kilbirnie for Barry Barclay’s short film, the eco-panto All That We Need (A Fable In Masks), with a small role by a very young Jane Campion. Morris: “Barry and Pacific Films had picked up a gig promoting, I think, Pink Batts. Being Barry, he turned the whole thing into a sort of concept album, involving masks courtesy of Ian Mune, and various wrong ways to go as far as conserving energy was concerned. We recorded it at pace; one or two takes for everything. Rough as guts, but at least we conserved energy on it!”

After two years, touring, and two albums, Tamburlaine’s new manager found the band a residency at the Casa Fontana, a coffee bar with, Morris recalls, “a dribbling fountain by the spiral steps … it seated maybe a hundred people if they were friendly. So full houses were the norm.” The band expanded their sound again, adding sitar and harmonium, more electric guitar and novelties like doubled-up recorders, playing a mix of originals and unusual covers. Hansen told the NZ Listener, “we’re refusing work elsewhere so we can stay in one spot and work things out.”

Tamburlaine had opened for big overseas acts like Tom Paxton and Mary Hopkins in 1972, and Don McLean in 1973, but the dependable university tour concerts, which had so nurtured the germination of a music for (as Morris says), “listening to [rather] than boogieing to”, were beginning to dry up.

“We unrealistically thought we might make a living playing in pubs,” says Robinson, “which is when Mark left … and we got our ‘full-kit’ drummer, Paul Davies.” Peter Woods from Nelson also joined on keyboards, and Winch bought a Gibson Les Paul Gold Top.

Morris: “We slapped together a pub-friendly repertoire of pop songs and hit the pub circuit. It was ghastly. We’d play with bozos who kept referring to us as Tramline, or Trampoline, both of which names were probably better suited to what we’d become than Tamburlaine.”

Robinson agrees. “It was the beginning of the end because we moved away from the concert scenario which was very much part of the uniqueness of Tamburlaine, and became just another pub band.

Morris: “The nadir was playing in Porirua East with Terry King, the 'King of Rock and Roll’ who was a true professional in the worst sense of the words. Paul and Peter were okay pub musicians, but they had as much in common with what Steve, Rob, Denis, Mark and I had been doing as the King of Rock and Roll. Within months it was all over.”

In March 2019 Kiwi Pacific re-released both Tamburlaine albums – ‘Say No More’ and ‘Rebirth’ – on a single CD.

Tamburlaine the Great was dead, but Morris, Robinson, and Winch all continued in music and arts. Hansen lives in Whanganui and is still a working musician, and Leong lost touch after settling in the States.

Winch joined The 1860 Band and became an in-demand session guitarist and bass player, working in television and film. He passed away in 2012.

Morris played bass with Ebony, and he and Robinson did session work with Alan Galbraith and commercial jingles before forming The Heartbreakers with members of Ebony and Bulldogs All-Star Goodtime Band. He is widely known today through his film reviews and production of Radio New Zealand National’s Standing Room Only arts programme.

Robinson has continued with film and commercial music, working with artists like Sharon O’Neill, Wayne Mason and Jon Stevens, producing and writing jingles and film soundtracks.

During the 1980s Robinson and Morris reunited for C&W band Punk and the Cartel (with RWP director Brent Hansen on drums, and Ian Morris on guitars), and they both continue to play in pickup bands with friends.

--

Update: in March 2019 Kiwi Pacific re-released both Tamburlaine albums – Say No More and Rebirth – on a single CD (Kiwi SLC-105). The albums, which were digitally remastered, were also made available on Spotify.

--

New Zealand green: read about Tamburlaine's lost, last song.

Denis Leong - guitar, vocals

Simon Morris - bass, guitar, mandolin, recorder, vocals

Steve Robinson - guitar, vocals

Rob Winch - guitar, vocals

Mark Hansen - drums, vocals

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air