The move to Avalon

Radio With Pictures opening titles, 1984. For several seasons in the early 80s the theme music was Marginal Era’s ‘This Heaven’.

In February 1980, TV One and South Pacific Television (later TV2 and TVNZ2) amalgamated into TVNZ, ending the era of competition between channels and ushering in a period of cooperation. For the 1980 season, the production of Radio With Pictures moved south to TVNZ’s Avalon studios in Wellington, where it became a stablemate of chart show Ready To Roll. Having established itself on a Tuesday night at 11pm in its 1979 season, Radio With Pictures stayed on a Tuesday but moved earlier to 10pm, and shifted to TV One for the first time.

Barry Jenkin: We rated our tails off, we did. It didn’t matter what they threw at us on the other channel, because there were only two, we out-rated them sort of two-to-one. They sort of lost control of it and they didn’t like that.

The opening titles of Grunt Machine, which ran from 1975 to 1976. Its final season over-lapped with the launch of Radio With Pictures. The animator was Mike Pebbles, a young TVNZ graphic designer based at Avalon.

Peter Grattan: The show is really successful, but then in 1980, comes a shake up, an amalgamation of TV One and TV2. We’d “competed” since 1975, TV One has Grunt Machine and Ready To Roll and has the state-of-the-art Avalon studios to do their music videos. But it isn’t always easy getting bands all the way out to Avalon. Remember too, all record companies are based in Auckland so it’s so much easier for us to produce Radio With Pictures in Auckland and to get a jump on them as a lot of the bands were Auckland-based. So, in their infinite wisdom, and needing to use Avalon’s studios, the new TVNZ bosses banish Radio With Pictures to Lower Hutt.

Simon Morris: What had happened was that it had originally been a clip show which was just basically some overseas clips and Barry Jenkin was the host and they put him in a closet as far as I could see; it was hardly a set. And he would just be out there and he’d be rather pompous and po-faced, sort of you know, “this is really important stuff”. And then for some reason they moved, I don’t even know why they did it, maybe because the pop stuff was coming out of Avalon and they decided it would make financial sense to lump them both together.

Peter Blake: With regards to RWP, its content reflected the alternative music of the day. Trends did evolve and we would try to appease a number of factions as they emerged. Its roots were new wave and punk from the Barry Jenkin days, so really it became obvious sorting the alternative and often interesting from the Ready To Roll pop clips that were made available to us. With both we would time screenings around record releases in most cases.

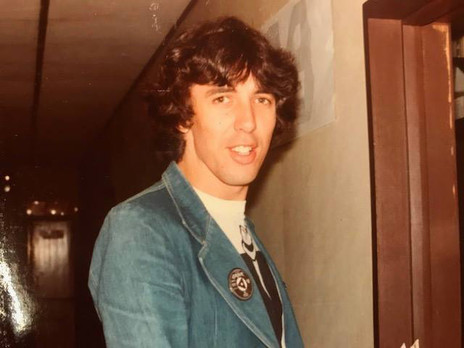

Phil O’Brien hosting

The first show of the 1980 season broadcast on March 11 and featured a new host; Barry Jenkin had been replaced by Phil O’Brien. But changes to the show proved unpopular with some of its punk-affiliated fans. A June 1980 edition of Rip It Up made reference to “Graffiti and posters on unguarded [Wellington] city walls calling for the firing of Phil O’Brien and the reinstatement of Dr. Rock,” and Wellington band Life In The Fridge Exists penned the ‘Phil O’Brien Song’, the lyrics of which included: “Phil? Phil! Phillip! Wanker! Wanker-wanker-wanker-wanker! Phil O’Brien! Bang bang bugger off!”

Barry Jenkin: I got fired! If anyone working in television tells you they quit, they're lying. I got up people’s noses for too long so they got rid of me. I didn't fall, I was pushed! I loved that show, so it pissed me off, and I took to my mattress for a while.

Peter Grattan: There was no budget to travel Barry Jenkin, and he was a “TV2 guy” so the new TV One producers found Phil O’Brien, a good radio DJ but not ideal for TV. Dr Rock was a hard act to follow.

¶ Wellington radio DJ Phil O’Brien had returned from a stint in Australia, working on Melbourne and rural ABC stations. He also worked for TV pop show Countdown, occasionally filling in for the legendary host Molly Meldrum. He jokes that his job was to “write the ums and ahs into Molly's script”.

Phil O’Brien: I was working at Radio Windy [Wellington] and we all got the call to audition. I just went out there for a bit of a giggle, to see what it was like. I never for one moment thought I would be able to do it, but there you go. Radio or television, I don’t know anyone who does both well. I can kind of do radio okay, I can’t do television okay. One of the reasons I left Australia was because I thought, I’m not really enjoying this being on television business. So why I auditioned again in Wellington I have no idea. I was young and foolish. Why I got it, I honestly don’t know because I wasn’t very good.

Phil O’Brien at Radio Windy in 1980, at the time of his Radio With Pictures hosting.

Peter Blake: Phil by day was a commercial radio DJ and I think this didn’t auger well with some of the hardcore RWP viewers. It was made more difficult by the fact he followed close on the heels of non-commercial Barry Jenkin.

Phil O’Brien: Tony Holden was the main producer. He was the only one I really dealt with. They used to have meetings and ring me up and say, right, here’s who is on the programme, go write your script. That was it. The programme had been very much Barry Jenkin’s up to that point. To be honest I didn’t watch a helluva lot of it because it wasn’t my kind of music. When Barry did it, there were all these bands doing their home-made videos and getting on the show, and Barry was being the spokesman for all these bands – and he did a superb job at it. Then when I got the job Tony said, right, it’s going to be wall-to-wall Fleetwood Mac, there’s going to be lots of commercial stuff here. So the programme changed format quite drastically, with what I think was not enough warning to the punters. I come along bright-eyed and bushy-tailed going on about how great Stevie Nicks is, and meanwhile all the guys in mohawks are sitting there going, who is this idiot?

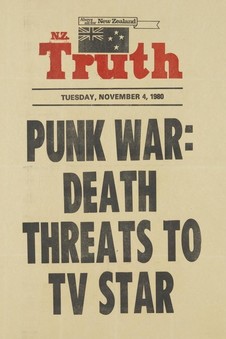

NZ Truth, 4 November 1980 - Simon Grigg collection

There was a poster put around town, a big A0 poster with a picture of me with a bullet going through my head, and a sign saying “Exterminate Phil O’Brien”. I thought this was hilarious until Bob Geldof held up one of the posters on stage at a concert and he said, “I’ve met this guy, he’s fine. What are you talking about? I’ve seen the programme. Leave him alone, he’s alright.” Up to that point, I got stabbed at a concert, they stuck a compass in my back – it bloody hurt – and they tried to set fire to my house in Brooklyn as well. I was the most hated man in town. To anyone who’d listen I’d say, “I don’t have any choice, I’m just a talking head, that’s all it is, they give me $80 a week …” Thank god there was no social media around, I would have killed myself. At that time Wellington wasn’t a fun place to be, to be honest. The punk thing was very heavy, full on, and it was very violent, and I win all my fights by a hundred yards. I remember going to concerts and having people just standing there chanting at me as I walked in the door. The punks. Life in the Fridge Exists did that song ‘Phil O’Brien’s a Wanker’ and then they got all shitty because they wouldn’t play it on television. Seriously.

Simon Morris: They objected to [Phil] because he wasn’t Barry Jenkin. And by the time they moved it down to Wellington I think that the producer, the interim producer, went a bit poppy which was a silly idea. But the weird thing was that after Phil left the whole theme went a bit poppier. Suddenly there was all this sort of New Romantic stuff coming out in the early 1980s: Spandau Ballet, Haircut 100, those sort of bands. So poor old Phil was prematurely pop; everybody caught up after that.

Phil O’Brien: I had no say whatsoever – seriously. I could suggest something, and it just became a running gag, oh yeah, here’s Phil’s suggestion, oh it’ll be the Kinks, it’ll be the Who. They would never play them. I notice Barry says, “don’t let people tell you otherwise, I was fired”. Don’t let people tell you otherwise, I had no say. What so ever. I was the front man, and I was treated with the disdain that most front people get treated out there, even though I was lucky, I had a really good crew. I knew I wasn’t any good at the programme, but I had to keep doing it.

I can’t even watch it now, if I see old clips, I can’t watch it. God knows how people watched the programme. I was contracted for 42 shows – a year – and I don’t think they wanted to go through the audition process again. Obviously they thought it was okay, even though I got a lot of bad press at the time. Colin Hogg, I’ll never forget, he just detested me – all these people wrote horrible things, I’d never met them in my life, and I’m sorta going, I’m not that bad.

Cartoon of Phil O’Brien, published in Rip It Up Extra, October 1980. The accompanying review was very critical: “It’s all just ‘great’ with our man Phil.”

Phil O’Brien: No, I don’t look back at it fondly, I just keep trying to forget it. I like the way people keep saying, oh yes, Radio With Pictures, Barry Jenkin, Karyn Hay – and they just skip over me, which suits me down to the ground, man, it honestly does! The minute that contract finished I was gone. I was out of there. I got out of the business completely after that, after RWP. It turned me off the industry so much, that I went to work for DSIR, doing marketing and stuff, which got me a trip to Antarctica, which was much more fun than doing Radio With Pictures. But then I ended up going back into radio. I was kidding myself. I wasn’t interested in television, but my love of music is such – and this sounds so clichéd – that I really wanted to share it. It stems from when I was nine or 10 years old sitting on the beach listening to a transistor radio on a Saturday afternoon, and thinking, that person’s got the best job in the world.

Karyn Hay: Well I don’t really want to be too negative about Phil, you know, and he laughs when I tell this story but it’s not something you want to keep hammering home. I just wrote them a letter in Wellington. I was watching it one night on TV and I fired off this letter saying, you know, I could do better than this guy … I remember later when I was working there – at some stage between 1981 and the end of 85 – I saw my letter in the filing cabinet so I read it again and thought “that was presumptuous of me!” Because it was written on a piece of ripped out school paper. Anyway, they wrote back and said “if you think you can do better, here’s your audition date”. But it wasn’t just the letter, because I was doing 7 till 10 nights on Radio Hauraki. I was the first female rock DJ in New Zealand, again it was a very male-oriented area. Peter Blake and Tony Holden had been up in Auckland and they heard me on Hauraki, so they knew who I was when they got the letter.

Peter Blake: Karyn wrote in during Tony Holden's final weeks producing and while I was being considered as producer, and yes, we had heard her on Hauraki. Given Phil was departing, Tony organised the auditions and incorporated me in the process where it was unanimous that Karyn be offered the position. Karyn felt right for the times. Her approach was assertive, her taste in music germane with the show and unlike Phil she was not strictly on or from commercial radio. We knew a different approach was required and the prospect of an assertive young woman fronting an alt show in a male-dominated television and music industry was appealing. I wouldn't say we were consciously trying to address the gender imbalance but just do what was fresh and right for the programme. We knew, however, that she would have a lot to learn transitioning from radio to television.

Radio With Pictures: Sweetwaters special, hosted by Dylan Taite (1980)

Karyn Hay hosting

In the 1981 season, Karyn Hay went from being the only female radio DJ to the only female host in New Zealand nightly television; she was also the first host in any medium to sport the quintessential New Zealand accent.

Simon Morris: So anyway after a year of that the producer left, Phil [O’Brien] left, Peter [Blake] turned up and he decided that we needed to get another front person. And he picked Karyn Hay largely because she was small and a woman and he thought that they wouldn’t be so horrible to her. But no, Karyn made it her own basically, so suddenly you got this deadpan Auckland sort of punky woman sort of hosting the thing and a new producer and you could do some stuff in the studio – so those are the things that changed I guess.

Originally intended for advertising use, this image by Philip Peacock shows Karyn Hay during her Radio With Pictures prime, with several leading New Zealand musicians of the era. It became the cover of Rip It Up’s December 1983 issue, a bumper Christmas special. - Murray Cammick collection

Radio With Pictures: A Pointless Exercise (1981). Tall Dwarfs Chris Knox and Alec Bathgate confront their past lives in The Enemy and Toy Love.

Karyn Hay: One of many groundbreaking things about that show was that they dared to employ a host who hadn’t had been through TV voice training or elocution lessons, so I just delivered the show in an ordinary New Zealand accent, which was the first time that had ever happened in this country. I did go to one elocution lesson. Supposedly I turned up – and I for the life of me can’t remember who the gentleman’s name was – but he said, “you’ve got a lazy tongue but it will be the making of you so go back and go for it”. And so I did and that really created so much discussion about my accent, which I had thought was quite normal.

Karen Hay interviews Split Enz for Radio With Pictures, Sweetwaters 1983

Bruce Russell: There was always the problem for me of who was fronting it because they certainly made an effort to promote the front people as personalities in their own right. The Karyn Hay era was particularly difficult. I kind of softened my attitude towards Karyn Hay over the years but at the time I absolutely fucking loathed her. I’m sure this probably wasn’t her idea but there was a period where every week she would be dressed in a different kind of style, she’d be a mod you know, then a goth, every kind of subculture. Occasionally they’d have interviews with like Dave Dobbyn and I can distinctly remember her asking with regard to the DD Smash album Cool Bananas, “how did you come up with such a crazy name?” You know. You can’t take that sort of thing seriously.

Karyn Hay: There’s the whole thing with wardrobe and makeup – you went through the mill in those days when you worked for Television New Zealand. I was put into a system in regard to makeup. Well, makeup was makeup but I look back now and I think you know, I was 20 – I didn’t need that amount of makeup. It was absolutely plastered on. There was a wardrobe department too, and it was a huge room with racks and racks of costumes and clothing, and they would pick out my clothes for me for that first year. Then I sort of rallied against that, as in “I don’t want to wear this clown costume any more, thank you”. That was what their idea of what “rock”’ was. So then we got various designers who I would wear; Wellington designers who were great and so that sort of evolved as time went on.

Radio With Pictures checks out New Zealand musicians based in Sydney, in the My Kind Of Town special (1981)

Simon Morris: And I think also that Karyn honestly didn’t give a shit, you know, she didn’t get huffy about what people thought about it and we didn’t really care much either you know. We just said “look, we’re going to do it, this is what we’re going to do”. And because Peter and Karyn and I were confident enough in what we liked as far as music was concerned, whatever anyone else said was completely irrelevant after a bit, so we just went for it.

Karyn Hay: My own music taste and my own interests gelled very well with everyone in the office in that regard. It was just a really great creative marriage in that office at that time for those years; it just worked extremely well. I was a cadet at Radio New Zealand, so I’d had that Radio New Zealand sort of bureaucracy and Television New Zealand was also state-owned, of course. But we were left to our devices in the Light Entertainment department and Peter Blake was a really good person to work for and he was also a musician, still is, and that made a lot of difference. Simon Morris was also a musician [see Tamburlaine] and their mindset was just different.

Peter Blake overseeing

By the end of 1980, Peter Blake was promoted from show producer to overall producer of TVNZ’s newly-invented Rock Unit. Having cut his teeth directing and talent coordinating on Ready To Roll and Grunt Machine in the 1970s, Blake now oversaw both Radio With Pictures and Ready To Roll, and would later add shows like Heartbeat City, Twelve O’Clock Rock and RTR Video Releases. Still in his 20s, Blake’s wide experience in, and deep connections with, the New Zealand music scene shaped the direction of these shows.

Peter Blake: I stayed connected with the scene, as I continued to play live. Broadcasting began as a day gig really. It was a way to pay the rent. But it was more than that; it was my interest as well, since watching NZ television music shows as a kid such as C’mon, Happen Inn and early music video fillers used when general programming ran under time. I had decided since early piano lessons that music was to be my life so wanted to be there in every way. I wasn't really part of the NZBC in-house establishment and was on contract or casual agreements that in early days allowed me to travel one week every month as part of the New Zealand band Quincy Conserve. We were on what was called the New Zealand Brewery Circuit. That was an arrangement where we would play Wellington six nights a week, then travel one week every month to a venue somewhere in New Zealand such as Auckland’s Mon Desir, Christchurch’s Aranui or the Shoreline in Dunedin. When travelling away I would scout locations for who was playing where, recording, developing contacts and keeping myself up with the scene.

Simon Morris: Peter had just taken over both of those programmes from, you know, grown-up producers and directors, but one thing that Peter had going for him was that he knew the music scene in this country inside out. And he turned out to be a very good producer, he was very capable and he could manage a very small budget very intelligently. When I joined there was Peter who was a producer, and there were two directors: me and Dave Brinkman. We were the guys who were putting Ready To Roll and Radio With Pictures together and putting it on air.

¶ Blake’s vision for these music shows was that they serve the public service function of promoting original New Zealand music. Up until the 1980s, the best – and sometimes the only – way for New Zealand musicians to appear on television was by playing cover versions of international pop songs; indeed, this was the format of Ready To Roll prior to the rise of music video. As a musician in the scene, Blake experienced first-hand the frustration of having few opportunities for original New Zealand music to reach the airwaves.

Peter Blake: I have to say being a musician myself, the concept of covers always grated. It seemed compromising. There were others in the 70s who felt similarly such as the late Bruno Lawrence of BLERTA and Malcom Hayman of the Quincys. They were averse, as Malcolm put it, to the “schmaltzy singers” on television. With the exceptions of the likes of Sharon O’Neill, Th’ Dudes, Split Enz and indeed BLERTA and The Quincy Conserve, the 1970s did not spawn a lot of radio-friendly original Kiwi music and the local recording industry was far from burgeoning. It seemed to me that to develop and foster a local industry, we needed to encourage composition and have more artists writing, recording and performing their own material. Who knows, it could eventually lead to record companies financing and producing their own artists’ music videos, as was happening internationally. Soon these companies might sign, record and distribute more local artists, and record-producers, recording studios and management would develop further. Radio stations might even play local content. Most importantly, perhaps, we could foster more acceptance of New Zealand music, thus higher audience turnout and higher record sales enabling artists to survive financially. Along with the phenomenal pick-up in international videos, this was my rationale behind decreasing and eventually dropping covers, but I knew it would be a long-term prospect. In 1981, I took over the producer role for RTR Countdown and Radio With Pictures and we continued to produce local clips and concert coverage of original New Zealand artists. Yes, there were success stories and some not so. We did have budget constraints, limited technology and time to devote to clips, but I do believe that this sowed the seeds for more awareness and confidence in original Kiwi music. NZ On Air has progressed the tradition further.

¶ Radio stations typically avoided playing New Zealand music, and one of the reasons they cited was that the audio quality of New Zealand music was inferior to overseas material. Television producers also faced technical challenges in making local singles fit for broadcast. Blake confronted the enormity of this task as unsolicited demo tapes began arriving on his desk from bands hoping to appear on one of the music shows. Many were cheaply made home recordings from bands in the burgeoning punk scene.

The Body Electric - Pulsing (1982)

Peter Blake: I was being inundated with cassette tapes from prospective bands with hundreds of fairly unpalatable punk/new wave songs where you couldn’t even hear the singer, let alone decipher a lyric. Every song often sounded the same, based often around the same three chords – what was one to do? You’d listen to the whole tape and try to find some semblance of order in one track or a melody or hook that would render the song interesting for television. In conjunction with my own recording experience, I attended a few record producer courses, one was with US producer Jay Lewis and another with Roy Thomas Baker who was Queen’s producer. I started producing records on my day off, being Sunday in Wellington. The motivation was really to help a little bit and get some of these bands sorted so that there was a quality-sounding recording which could then be used as the basis of a clip. There was a label in Wellington at the time called Bunk Records run by a guy called Mike Alexander. He would take some of the recordings and distribute them as singles for the respective bands. One example here would be Wellington guitar three-piece punk band The Steroids, a band who, after I popped some synth on their track, got me playing live with them a couple of times. [Laughs] I was sure I would collect a beer bottle on stage. Alan Jansson was the guitarist/writer who went on to be one of Auckland’s top record producers, recording the massive hit ‘How Bizarre’. The Steroids morphed from guitar punk to the synth electronica Body Electric for whom we also made videos. Others included The Mockers, Phil Judd and Dunedin group The Knobz. Their song was ‘Culture?’ and a dig at the then Prime Minister Robert Muldoon’s ... sales tax on music. I slapped a Muldoon voice impersonator on the recording which worked well with the message of the song. After our video played, the record received a lot of radio airplay and charted. As the industry and recording standards developed, I left it to the experts but I was trying to get some order into things from the audio side of things.

The Mockers - Forever Tuesday Morning (1984)

How the show was made

From 1981 to 1985, Radio With Pictures settled in to what many viewers would consider its classic era, with the show scheduled to precede the Sunday horrors (which began June 1981). This version of the show featured Karyn Hay hosting, Brent Hansen producing, Peter Blake overseeing, and direction duties shared among the likes of Simon Morris, Dave Brinkman, and Irene Gardiner. Each made important contributions to the look and feel of the show, and everybody got a say in determining the week’s playlist.

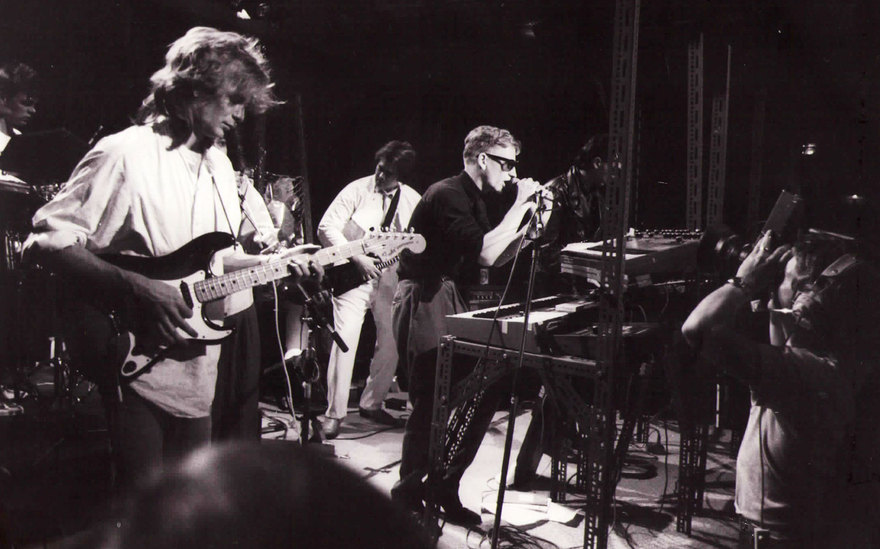

Car Crash Set: Simon Mark-Brown, Trevor Reekie, Ryan Monga, Nigel Russell, Dave Bulog – Radio With Pictures show, Quays, 1984

Brent Hansen: Even though I was a public service guy, I refused to have a set made by television people. I wanted the money to be able to use somewhere else and I contracted a guy called Malcolm Bennet to make the set. And I got Fane Flaws to make the titles and Peter Dasent [The Crocodiles] did the music. So I did that independently of TVNZ.

Karyn Hay: I wrote the scripts, so that was down to me … one of the drawcards for doing the show. I would go through it with Simon Morris and, later, with Brent Hansen when he came on board as a director. I really liked that because it gave me my own style; I wasn’t reading something that somebody else had written. I’d written it and so I was able to really be myself in that regard, even though a lot of people would say that my style was pretty laid back. That’s just me, I was actually just being myself.

Brent Hansen: We were cultural gatekeepers at a time when not much of this material was being seen anywhere else, so we tried to present as eclectic a mix as possible. It was important that the metallers and reggae guys and punks and psychobilly fans all got something they wanted in amongst other stuff they just might enjoy despite themselves.

Karyn Hay: We all gave it the ultimate sign-off. There’d be too much to play and so things would have to be dropped. We used to laugh about playing heavy metal. I think Simon and Peter liked heavy metal, they liked to tease me about it anyway. I’d be like “oh no”, groaning having to add that into the mix – but in hindsight it was a good cross section of music. Someone said to me recently they’ll never forget the line, “Here’s one for all the panel beaters out there.” We didn’t really veer into the pop area very much. I think we played Boy George the very first time that came out, ‘Karma Chameleon’. We might have played it once and then it went to Ready To Roll. We’d play it because it was a new video and the person was going to be huge but other than that we would play the stuff that Ready To Roll didn’t play and that was always a group discussion. It’s just how things evolve in an office, you know, “I like this and don’t like that”, so yes it was definitely a hands-on thing.

Radio With Pictures, 1982: Dylan Taite interviews The Clash at Auckland railway station.

Simon Morris: There was always a big screening each week. The directors would normally sort of roll them in. They would come in on separate tapes and things like that, we would compile them onto a viewing thing. And then I think Tuesday afternoon, we’d all sit around the place and watch these things and react one way or the other. There would be an instant reaction generally, say “this looks like complete shit; I won’t go and look at that thing there” you know. And Peter [Blake] to his credit would always keep an eye on whether the thing was shouting or not because after a few months of watching these clips you sort of lose all sense of objectivity about it completely. You know, just all you’re doing is instantly reacting to it on a personal level rather than thinking “well, we better play this cos it’s number one in America”.

Karyn Hay (on deciding which clip for which show): That was Peter Blake’s job really and he had an inherent feel for that, he knew what would work on RTR and what would work on RWP. I think he would sort of filter out anything that would be regarded as dross. He had really good taste. Even though his own music sense was in the jazz arena, he knew what would work on RWP. There was never a situation where he missed anything, so I think his filtering process must have been very good. And other stuff, we would all be bringing that information to the office. The years that Flying Nun started making their own videos, Chris Knox started making his own stuff, I championed that a lot and the New Zealand music end of it. We had a big focus on New Zealand music.

Chris Knox directed the Tall Dwarfs’ clip for Nothing’s Going To Happen using stop-motion animation (1981)

Simon Morris (on deciding which show a clip belonged on): Usually they pick themselves really. I mean, the fact was that if it’s a charting song then it would go on Ready To Roll, but sometimes it would be a thing that it was only going to chart if it turned up on Radio With Pictures to start with. And then I remember there was a song by a group called Freur called ‘Doot Doot’ and we absolutely fell in love with it, we just thought it was the world’s greatest clip. It was this psychedelic band from Wales. And it was only ever a hit in one country in the world and that was in New Zealand because we would thrash it, and we thrashed it cos it just looked so good as much as anything else so it was very much a Radio With Pictures-type clip but it crossed over because it was a big fat hit.

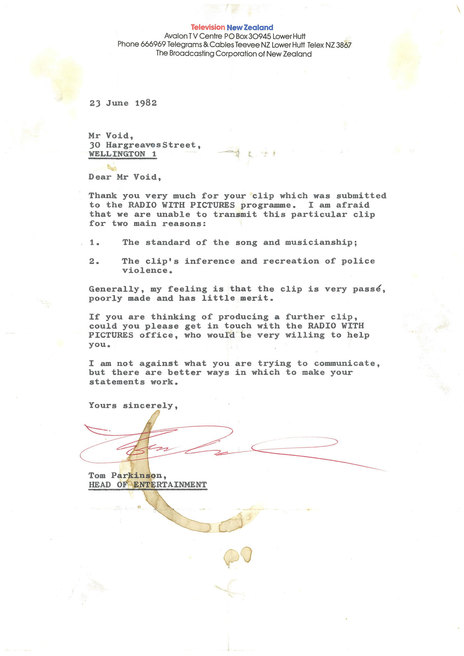

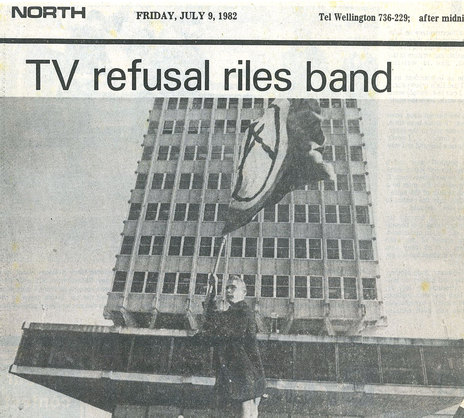

Peter Blake: There were technical standards, so clips – like all broadcast content – were vetted by TV’s technical people. There may have been a rejection or two. Obviously content was important as in if there was anything a bit dicey that would prevent it going on. Censorship was far more stringent in those days. One example here was a Wellington band named Riot 111 who had submitted a video. It portrayed violence against police and I made the decision not to screen it. The band responded by demonstrating outside of Avalon television complex. There was an entourage of media and associated friends gathered for the occasion. They parked outside my office on the second floor and spent the afternoon performing on the back of a truck in between loud hailer obscenities. Of course, that was the best publicity they could ever get [laughs]. I think we might have had a camera down there as well as the 6.30 news.

The letter from TVNZ to Riot 111’s Void. - Redmer Yska collection

Void in The Dominion, July 1982. - Redmer Yska collection

Simon Morris: But we didn’t give a shit you know; [if] it looked good or it sounded good or we liked it, it would go on.

Brent Hansen: And I was the only one who wasn’t a musician; Peter Blake and Simon Morris – those guys were musicians. I was a music fan who had been given a lucky job; like being a librarian at a great library. I mean that is what I was doing, so I just wanted to do the best job possible.

Peter Grattan: Brent Hansen and Peter Blake really enhanced the show. Their music knowledge and passion was second to none and they could do things in Avalon with its awesome facilities that we could only dream of in Auckland. Brent deservedly went on to become President of MTV Europe.

--

Read Radio With Pictures history 1 - here

Read Radio With Pictures history 3 - here

Read Radio With Pictures history 4 - here

--

Other sources

Thanks to our colleagues at NZ On Screen

Phil O’Brien interviewed by Chris Bourke, Wellington, 14 June 2018

Grant Smithies, “Radio With Pictures: forming the musical tastes of a generation”, Sunday Star-Times, 27 March 2016. Stuff.co.nz

Bill Roedy, What Makes Business Rock: building the world’s largest global networks, Wiley, Hoboken NJ: 2011

Michael Flint, “What the air was like up there: overseas music and local reception in the 1960s”, North Meets South: popular music in Aotearoa/New Zealand, edited by Philip Hayward, Tony Mitchell and Roy Shuker, Perfect Beat, Sydney: 1994

John Dix, Stranded in Paradise: New Zealand rock and roll 1955 to the modern era, Penguin, Auckland: 2005

Wikipedia entry on MTV