Promotion of New Zealand content

Radio With Pictures wasn’t just a repository for music videos; it was an active producer of music video content for New Zealand bands. Part three of this series focuses on the show’s role in promoting and producing New Zealand music, particularly Avalon’s emergence as a factory for making music videos.

Until the 1980s, most New Zealand music television shows relied heavily on local performers covering international hits live (or mimed) in the studio. The covers invariably paled in comparison to the originals and conveyed the notion that New Zealand cultural products were naturally inferior to those from overseas. This contributed to the country’s well-documented “cultural cringe” regarding home-grown products, an attitude that proved an obstacle to getting New Zealand music played on local commercial radio. One of the features of Peter Blake’s stewardship of TVNZ’s Rock Unit was its aim to alter the general perception of New Zealand music and in doing so stimulate original music making in the local scene.

Peter Blake (producer, Radio With Pictures): I always thought that in terms of promotion, television was in the best position to lead. I thought radio would have followed for the ride, but it was slow. It was my great wish that radio would start playing more local music as it really was the hit maker, television the hit breaker. As I said earlier, my career in broadcasting started in radio prior to television. Ironically, one of the people who I programmed for was Barry Jenkin, who was in the early stages of his broadcast career at the Palmerston North radio station. Anyway, that’s by and by. So I kind of knew my way around radio a little bit and I enjoyed listening to it and studying playlists. Occasionally, I’d be asked to talk at the induction of new radio programmers by Radio New Zealand, so I had a connection and I knew that their culture was American music and very little emphasis was given to New Zealand music. I’m not saying I was responsible for what’s happening today – there’s been a lot of water under the bridge since the 70s and 80s – but I certainly think things have picked up considerably locally and that’s great.

Brent Hansen (producer, RWP): The role of Radio With Pictures as a whole was as a public service. We took it really seriously and there was so much debate. We worked long hours trying to get things together for it, even though sometimes it looked a bit amateurish at times. We saw this as a channel of record. Not only for our local music but primarily to make local music work – [and] to have it sit in parallel to what was happening contemporarily. ‘Totally Wired’ by the Fall, then ‘Beatnik’ by The Clean – why not? It made total sense, and Accept’s ‘Midnight Mover’ – some German metal band – at the same time. Possibly Boz Scaggs, possibly Howard Green – a fantastic snapshot of what was there. And that is why the programme was so important. I am sure that people sat at home on Sunday night watching that programme and were just moaning and groaning about everything because we were all very subjective about what we like. But this programme tried very hard not to patronise and you had to make sure that you were giving everyone a decent crack of it.

Peter Blake: But an environment of public service did exist through all departments, whether it be drama, documentaries or music. During my 15 years in television, Grunt Machine started the tradition of being predominantly a New Zealand content series and record industry-based Ready to Roll came along with local pop cover versions. Yes, I and others carried it on into other series formats which developed into international/local shows as more clips arrived from overseas. In terms of an edict from above – “you must put local content on” – no, there wasn’t. I guess being a musician myself and understanding the power of television and how it can promote, I thought it important that the lion’s share of the budget went into promoting local music.

Simon Morris (director, RWP): The wonderful thing that Peter [Blake] did was that he decided he was going to try and get more New Zealand music on TV which meant getting video clips up.

Peter Blake: As mentioned, my knowledge of local music in the 70s and 80s was quite strong. I had toured and continued playing with various bands myself. After The Quincy Conserve it was The 1860 Band. I knew the scene, which enabled me to make talent decisions. Later, as bands began recording more, I would be supplied with demos or in some cases final products to assess suitability. Some would come via record companies and some via band management and promoters who were growing in numbers – a lot came directly from the bands. The late 70s and early 80s spawned a lot of punk music so you would end up with a cassette of about 100 demo songs to wade through.

Brent Hansen: I personally think we would have been better to have gone the route of the Old Grey Whistle Test and pulled the cycloramas away and just had the sound baffles on the wall and shot everybody the same, everybody in the same neutral space. Because at this time, unlike later in the 1980s, early on everybody who came into the studio could play. Everybody could stand up on stage. You had that tough music circuit here and, if you were lucky, Australia – which was even tougher. It was a hard-arse lifestyle and you had to be able to play against all odds and be quite together and quite proficient. So they were proficient. Some of them were successful and some of them weren’t successful, but every now and again we were able to shoot something on film.

¶ Although Radio With Pictures became more famous (or infamous, in some cases) for the music videos it featured, it frequently showcased live performances as well. These weren’t performed in an empty studio à la Britain’s Old Grey Whistle Test. Instead, they were recorded in front of braying live audiences at various notable live venues around the country. These occurred sporadically in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but under Peter Blake’s stewardship they became a regular feature of Radio With Pictures. Known as the Live at Mainstreet series, they featured professionally recorded performances by two bands at a time. Bands could later release the audio as an album.

Peter Blake: In the 1980s, Mainstreet was the largest live performance club venue in Auckland, at the top of Queen Street. While working in conjunction with promoters, I would decide on two professional-level bands such as DD Smash, Coconut Rough, Hello Sailor, who would give great performances. We would organise and publicise their public concert at the venue, covering it with our multi-cam outside broadcast gear. This included cams, additional television lighting and outside van with director and technical, etc. It was imperative from my point of view that we would get the best sound quality possible. So rather than just record it through TVNZ channels we would incorporate an independent Auckland recording studio who would multitrack the live sound. They would then mix sound back at their studios to the highest possible quality, sometimes in conjunction with the bands’ record producers. We would take that final stereo mix and transfer it back to video, which is what ended up going out on air. But there was more to it. The bands’ record companies would release the audio mix as a series of live albums called Live at Mainstreet. Further, in those days transmitted television audio was in mono, but how to transmit our audio in stereo? I set up what I believe to be New Zealand’s first stereo radio simulcasts. So on the night the concert screened on RWP, it could be heard in synch on FM radio stations around the country. That led to cross-promotion beneficial to all parties, including the bands. And importantly, the viewer benefitted from quality stereo sound. Over the series history, there were other concerts covered in locations such as The Christchurch Town Hall, Wellington’s St James Theatre, Auckland Town Hall and Sweetwaters music festivals. The beauty of the Mainstreet series was that the bands had more control over their final recorded sound.

Harlequin Studios' engineers (including Doug Rogers, centre, and Paul Streekstra, stripes) recording for the Live At Mainstreet series of albums.

Producing clips at Avalon

Production of Radio with Pictures moved to Avalon studios in 1980, around the time that music video was becoming increasingly central to the industry. Internationally, pre-packaged conceptual videos were beginning to take precedence over Old Grey Whistle Test-style live performance on television. After MTV’s introduction in 1981, music video was an indispensable part of music promotion, and increased the urgency for local music videos to be made.

Occasionally record labels paid for bands to have videos made, but this was rare. Producers of shows such as Shazam!, Ready To Roll and Radio With Pictures took it upon themselves to arrange for video clips to be made so there was local material to match the flood of MTV-inspired videos arriving from overseas. While Auckland-based Shazam! often outsourced production and relied on location shoots, by the 1980s RTR and RWP produced videos in-house at Avalon’s studio facilities. As a 1982 Listener article by Frank Stark wryly noted, “Avalon has had to become a part-time rock video production house – producing a volume of work that overseas companies would baulk at, on a budget they would laugh at.”

Peter Blake: As international record companies realised the power of video clips on record sales, they threw more and more money at them and production standards increased. And what were we to do in terms of our local input? I was determined to keep the genre and have New Zealand music represented the best it could be.

Simon Morris: That was Peter as much as anything, which is how we managed to get so many video clips through. He really pushed for it, saying, “look, so long as we don’t spend any money, we can make as many clips as we can physically do,” bearing in mind that we’ve got like one day every fortnight or something. But suddenly there was a whole lot more New Zealand music being made. In the old days you’d have to go through some sort of screening process whereby only professional bands would be there and they’d be given a pop song by EMI or something like that and do what the record company told them. But then Flying Nun turned up and had pretty much the same ethic that we had, which is you know, “we’ve got four hours, let’s make an album.” And once you can do that, once it stops being a stigma and you realise that this is no worse than something we spent a month on in a bloody professional studio with a whole lot of bored operators, then suddenly it became a lot more fun.

Peter Blake: Every year I would lobby TV’s head of entertainment, my boss, for an increase in above-the-line series budget funds, not only RWP but RTR and others. He would allocate these as he saw fit and it was usually a struggle, to be fair. Remember, the budgets covered not only in-house clips but other costs such as local concert production like the Mainstreet series, international concert purchase, independent filmmakers and crews, travel, office, general above-the-line expenses. I was always keen on a balance of local clip content, however, so the pressure did go on and generally we were under-resourced there. Sadly, music video production independent of TVNZ was slow in coming.

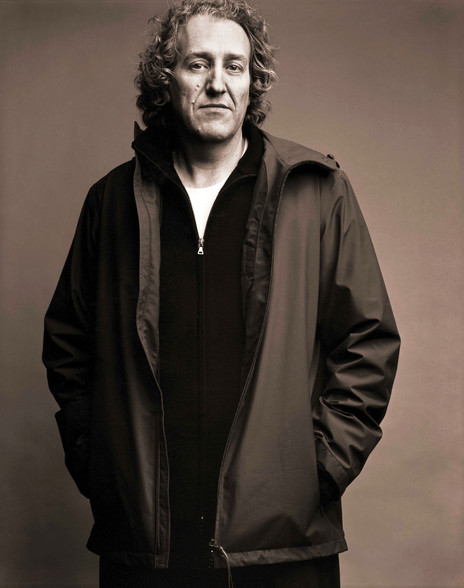

Brent Hansen in the 2000s, when he was head of MTV Europe. - Jonas Karlsson

Brent Hansen: [In the late 1970s] South Pacific Television itself had … there was a lot of time. You were paid to do an eight-hour shift, so if there was nothing on, obviously there was nothing to do. If you finished early in the studio you could go home, but those of us who were keen tended to stay around. And because we had some time quite often in Christchurch regularly, entrepreneurial bands would contact South Pacific Television and they would get slots to come and make music videos. I remember when I first started as a floor manager there was a DD Smash one, shot in one of the studios just down the road from here [in Christchurch city]. Citizen Band with Mike Chunn had sponsorship from Citizen Watches and it was full on. They got flights down here and they were doing stuff – so stuff could be fitted in here around other work, which was one of the ways in which product could be made. Sometimes the bands instigated it – sometimes the record labels were looking for space. I don’t know who made the decision because I was obviously at the end of the line in the break time but Television New Zealand essentially, for most bands, was an opportunity right through the time that I was working there. With the possible exception of Flying Nun who, even though we were huge fans of them, I always got the impression that they treated television with disdain and didn’t want anything to do with it. And consequently had better and much worse product that they produced themselves.

Ian Morris (Th’ Dudes, Tex Pistol): Back in Th’ Dudes’ days, all the videos were shot and paid for by the state. If you had a song you wanted a video for, you’d get flown down to Avalon studios in Wellington and the state would shoot your video for you.

Peter Blake: Funding for video or film clips came from the programme’s budgets. Often for Avalon-based video studio clip productions, I would tie-in with bands’ tour dates to save on travel costs. This in turn generated publicity for their tour, coupled with plugs on our tour news section. In most cases, we would pay a performance fee – minimal, but it helped the group or artist with personal costs.

Andrew Fagan (The Mockers): It wasn’t airfares; it was train. We did the trip from Auckland to Wellington, the overnight train without having any bed.

Peter Blake: We just paid general expenses to the band. Not in all cases were performance fees paid. It depended on the cost to us. If we were shooting a film clip on location it might not happen because the above-the-line expenses were more than putting a band in our Avalon studios.

Brent Hansen: I think we were still pretty much making them until I left at the end of 1986. So it was still there, it was low budget and it didn’t cost anybody anything and it wasn’t being funded by an outside party. It wasn’t being funded by NZ On Air. It was being funded by our budget that had already been paid for by the taxpayer. So budget was never a negotiation, unlike my world at MTV when it was hundreds of millions of pounds and that would make a difference in terms of potential and growth and expansion and [generating] division income. There was none of that. You just got given your time and off you went and “don’t stuff up”.

Andrew Fagan: The incentive from the system was very good. It was public service videos. It was public service broadcasting at its best – or at its worst – but with the best intentions.

Liam Ryan (The Narcs): But we were lucky. The band, in that early phase, had this mix of having videos paid for by the record company and if that didn’t happen – when the money ran out, as it kind of did – then there was a phenomenon that happened at Avalon. On Wednesdays, I think it was, Simon Morris had a team in there and they would bring bands in, spend an afternoon with you to record a couple of videos. Maybe a Narcs one between 1 and 3 o’clock and then between 3 o’clock and 5 o’clock they’d do the Mockers or something like that. The video to ‘Heart and Soul’ was done that way.

Simon Morris: Every couple of weeks we would have a studio booking, and there would be eight hours or something like that and we were allowed to do what we liked in that studio so long as we don’t spend any money. So we would get bands in and Peter would often pick the bands and he would sort of flick a couple of songs at us and say, “they want to do this as a single,” and Dave [Brinkman] would pick up a couple or I’d pick up a couple and we would just teach ourselves how to do it.

Brent Hansen: We would knock three of them off in a day and the bands would come in and do their piece and at the end of the time the band would leave. So it was pretty rough and ready. The shoots would last two and a half hours, max. Not much when you consider that part of that time was actually pointing and lighting. You would get a few passes at it so you would have to find a way to do it.

Alec Bathgate (The Enemy, Toy Love, Tall Dwarfs): You’d go down to Avalon and I think the first one I remember we were playing in New Plymouth, and we flew down to Wellington for the day and got taken out to Avalon, and we had no involvement in what they were doing. You’d just turn up and there would be a slot where they’d be filming your sequence, and we’d just mime for the recording. So you’d just get put into a room and there’d be a director and cameras and they’d be like, “stand here and do your thing”. So there was a clip for ‘Squeeze’ and it had an opening sequence, it was like red paint or something spilling out on the floor, it was supposed to look like blood, I think. I remember they kept us waiting in the break room, because they were filming this opening shot, it was probably a couple of seconds long but I think they spent all their time on that. So we just came in and mimed to the song, and I don’t know if it was the same occasion, because there was another song we did, it might have been ‘Rebel’. We did ‘Don’t Ask Me’ there, but when we were doing a Toy Love DVD a few years ago, we couldn’t find the video of ‘Don’t Ask Me’, I don’t know if that exists anymore.

Chris Knox (The Enemy, Toy Love, Tall Dwarfs): There were two that were made down at Avalon, which Tony Holden had a hand in, one for ‘Rebel’ and one for ‘Don’t Ask Me’. The ‘Rebel’ one was trying to emulate A Hard Day’s Night sort of thing, black and white but with a little bit of red or something. And I think there was one done for ‘Don’t Ask Me’, but my memory’s pretty loose for that period. Both of those were probably shown a couple of times and then the tapes were wiped or recorded over for a Nivea ad or something.

Alec Bathgate: We did a clip for ‘Rebel’ that they shot in black and white, and when we turned up they had made all these Beatle wigs for us to wear, because someone had listened to it said, “oh, it’s got a kind of 60s feel, we’ll get them to wear Beatle wigs.” Except they couldn’t find Beatle wigs so they just got some black wigs and cut them into like a pudding bowl, which we just refused to wear. I seem to recall the makeup lady was quite upset that we wouldn’t wear these wigs because they’d gone to so much trouble, but it was just ridiculous. That’s how it worked, they would have been producing these things super fast because it was a weekly show. It was probably shot on Wednesday or something and edited then shown that Saturday (RTR) or Sunday (RWP) night, and those things were only ever intended to be seen once, so they probably didn’t take a great deal of care over them.

Brent Hansen: Peter Blake, who was the producer when I arrived there, would just say to me, “next Tuesday you are doing Blam Blam Blam.” We would call up the artists and have a conversation with them. Some of them were ridiculously ambitious and you can usually tell that when you see them, and some of them were more straightforward. I had no experience, you know, you just do it. “You’re a creative type, go do it.” And I was learning to roll compilation tapes in the studio, learning about telecine and links and microwaves – there was a lot of stuff to learn. It was quite complicated and they expected you to know a lot. That’s what I’m talking about – no training at all. So I don’t know how the choice was made about how these bands were given the opportunity to come in but I am assuming through their labels.

Simon Morris [on whether he enjoyed being asked to make videos]: No I hated it but I mean you got thrown in to it, you know. Partly the reason I hated it is cos I was seeing all these kind of things from Godley and Creme and Russell Mulcahy and those guys, and thinking, “Jesus Christ!” I mean, no wonder they look good, they certainly had a lot of money chucked at them. I guess back in those days it seemed like a lot of money and I guess these days it wouldn’t be as much but it was still really good. Because we were doing them in the studio and we had to do them with multi cameras, it meant that you just have to cut away there and get it done. You had around about two hours to make them with no sets and you had a bunch of camera people, some of whom were keen on it, others who couldn’t wait for it to be over. And also the fact that I’d only just started out and I knew absolutely nothing about directing. And god no, we got no training, none of that. My background was music and writing, so I had nothing to do with any of that sort of stuff. I mean Brent [Hansen] to his credit had a really good eye, and I thought he made some really nice videos. The times that I enjoyed them most was when I was allowed to go and make a film clip [on location] because you’re dealing with one camera and you could do it shot by shot and you can actually concentrate a bit on it, whereas if you’re doing it multi camera you’ve got three minutes and half of these things are whizzing past you so quickly they’re going, “oh I don’t know, did that shot work?” ... “I have no idea.”

Brent Hansen: Well, first and foremost, the role of the director was get the damn thing done in the time so there was something in the can, that in my two hours of editing I could actually knock something together. So it had to be simple enough that I could stitch it together with a few bits of wiggle room that I could place. It was not highly ambitious in terms of the amount of stuff that I could shoot. I wanted to do a really good job and some of them were better than others. I played around with things and the byproduct was that I learnt some good creative things and learnt to think on my feet. Not to expose things I couldn’t do as the bands invariably wanted something more than we could actually deliver. But I didn’t want to let them down either. I thought – one, get it done and the second priority would be for the band to at least feel okay and that something had been worthwhile and they weren’t just being put through the mill in some kind of foreign environment. And third – it should have been the first thing – which was could I entertain the audience. But to be honest, with those constraints I think the most important thing was to get something done and keep it as simple and straight forward as possible so that you didn’t compromise the artist.

Liam Ryan: So actually the standard of stuff whether it was financed by the record company or by TVNZ tended to be pretty good, although when I look back at ‘Heart and Soul’ and see that shitty bloody triangle that they probably made out of scrim – what the hell that all means I don’t know, Andy staring into a triangle, big deal, you know. I mean, that was the thing that pissed me off in the end, that the songs always seemed to have “meaning” – you know, they wanted to have “meaning” with them.

Dave Dobbyn (Th’ Dudes; DD Smash): The art direction was already set: someone’s built a set, which usually resembled something out of Dr Who, and it wobbled. And there was smoke, always smoke, lots and lots of smoke. You’d be coughing your way through these sessions and go through this thing and rehearse for camera god knows how many times, so the band would always end up exhausted. You’d be dripping with sweat, and have gone through the song many times.

Simon Morris: We were allowed to edit later on after the shoot but editing was so primitive that half the time you couldn’t even see the shots going through. But you’d sort of vaguely think, “it should go there, it would go there,” and it wasn’t until you’d actually done it that you could play it back and have a look at it. I mean it was unbelievable, the fact that you were sort of editing blind basically in a lot of these things, which is fine for sport, because sport you can say, “here’s the action replay, it happened there,” just whiz back and do it, you don’t have to worry about what it looks like because you know what it looks like. Making a video clip like that was kind of nonsense. But every so often a special effect would turn up. I remember when a frame store [image memory] turned up which gives the whole thing a jerky sort of a look and you think, “oh wow that will be good,” and that got used on every single clip three or four months after that. And then there was another thing called “the white out” which is one of those things I associate with 1981, where you’d have incredibly bright lights and a very white set and so everything looked very flarey and 1981-ish. That got thrashed a lot too.

Brent Hansen: The idea was to be as different each time as possible given the limited scope that we could play and what was thrown at us in terms of studios. You can see if you look at my ‘Luxury Length’ video with Blam Blam Blam, it is just against a coloured site. I just didn’t want that stuff. In the end it was put to me that it would have been a good idea to use things that were available, so unfortunately it sets it close to home. So I would always lean towards the simple. The Mockers [‘A Winter’s Tale’], that was basically done on one camera. One shot. We just went around everybody and I thought, “forget it – let’s just get rid of all those things, try not to compromise too much on the ground rules of television.” I don’t know who did that but whoever did it was a brave guy. It was a big Marconi Mark 8 camera on a fat gas pedestal with his assistants on the floor pushing the camera around. It was serious. Those guys were brilliant – those studio cameramen, they are the unsung heroes – they saved my arse. So was I aiming for anything in particular? Not really. Could I come up with a Ralph Records copy of something like ‘Fish Heads’ or ‘Land of a Thousand Dances’ by The Residents? Well, I didn’t have the money. Even though it was done on a budget, three hours in the studio wasn’t going to get you much. The first hour is going to be blocking and lighting, people tapping the blondes and the redheads around. So television is essentially a practical thing; you have to be able to deliver it as well as be creative so we were pretty thwarted in creativity because of budget and time. So I always looked at it just to be sensible. But you would get a band who wanted a chroma key of fires and things that bleed out but I just let it go – I just let them run with it and we made it somehow over the tyranny of distance and time – it doesn’t look as bad now as it did at the time.

Simon Morris [on communicating with bands prior to the shoot]: You could ring them and tell them roughly what you planned to do or not. I mean mostly they would say, “oh whatever you like,” you know, or if they did have an idea it was something that was absolutely impossible. They were looking at video clips and we were saying, “well we can’t do that,” you know, “we can’t do that one either, trust me it will be fine,” lying furiously to these people! But I remember getting into trouble. Gosh, The Chills got really huffy because when I did a thing where I tried to turn them into a pop group, they bitterly resented that. They wanted to be grimier and grubbier and all that sort of stuff. Some of them worked out, sometimes it didn’t. The ones that worked out best are the ones where the performance is good, where the band just had a good feel for performing in front of the camera and it made it work.

Brent Hansen: Andrew Fagan was pretty good to deal with, to be honest. The poor guy got lumbered with me doing so many of his videos and reasonably cheap and nasty ones as well. But he was a good guy – he was keen. He would come into the office and sit there for hours on the floor and talk it over … so when that happened and people made themselves available, then your job was to harness that.

Liam Ryan: So we dropped in off the road, you drive in to Avalon for lunch, they’d put you in the green room and you’d just be called in and they’d say, “this is the set, you set up over there, you set up over there,” and that was it, you know. It was kind of like you just kind of did what you were told, it was funny. So we didn’t have any investment in that at all.

Dave Dobbyn: We’d all get out of there and cross our fingers, and have no real input as to how the thing turned out. Just sort of “take it or leave it”. The effect for us in Th’ Dudes anyway was, “well, there’s the video, there’s the radio play, there’s the band touring,” so it all connected, it worked. As horrendous as it was, it worked.

Simon Morris: Bands had no say in editing it; they had a bit of say going in. I mean the reason they didn’t have any say editing it is that half the time we had no idea when we were going to be editing, you’d do it and say, “can we have a bit of editing time?” They’d say, “yeah you can have an hour and a half on Tuesday night,” and no band wants to drop everything and come out here at that stage. I mean once the stuff started being shot on film I think that maybe the bands got involved in a little bit more after that, because it’s just down the road and it’s kind of quite handy. But Avalon’s such a bloody long way away and a lot of these bands would fly in that day, do a gig, do a thing for Radio With Pictures, fly back to Hamilton or Dunedin or Auckland or wherever they came from.

Brent Hansen: The last word was with the director but – the kind of people we were at Radio With Pictures – we weren’t just robotic types, we tended to be collaborative. And I think that it would generally be a conversation.

Karyn Hay (host, RWP): Often [the bands would] not be able to wear what they arrived in. They’d be taken down to the wardrobe department, which was huge, and I remember many a time going to the wardrobe department before a show, before Radio With Pictures, and being kitted out for what I was going to wear that night. Simon [Morris] was the worst; Simon would go, “alright everybody, down to the wardrobe department! Right, you’re wearing that, the drummer’s wearing this, and you’ll wear that,” and the poor bands are going, “Okay, but the jacket’s too big.” “Oh, it’ll be great, you’ll look great, we’ll just put some Vaseline on the lens, nothing will go wrong here!”

Simon Morris [on resources at Avalon]: You’d look at your watch basically, and say, “we’ve got 10 minutes; shall we pop down and see what they’ve got in the costume department?” I mean basically you walk out to Avalon and whatever you can see you could have, pretty much. “I’ll have that,” you know, you get in touch with the design people and they would maybe have three or four hours set aside to do something for us, “could you give us a background?” or something like that. “Could you get something that looks a little bit like a street scene, could you get something that looks a little bit like a stage, could you get something, I don’t know, sort of balloons maybe, can we do balloons?” And they’d say, “Well, I can give you some balloons or something.” But they rather enjoyed it too, I mean people like doing video clips after a bit, even if they did look a bit shabby, because it was fun, like a little party. In a sense it didn’t really matter what it ended up looking like, everybody did the best possible job you could in two and a half hours and, if you were lucky, maybe an hour and a half with some editing afterwards, or not.

Brent Hansen: For actors, I would either cast at the ballet school or I would cast at New Zealand School of Speech and Drama or Toi Whakaari, they were very helpful and would give me staff and I think I used Jon Brazier [Outrageous Fortune] on a couple of things.

Simon Morris: Most of the actors were people that I knew and I said, “do you want to make a video?” and they said, “oh alright then.” It was a bit like that; it was a bit, “hey mate, do you want to do something?” Like when we did ‘Victoria’ [by the Dance Exponents] down in Christchurch, which is a thing on film. Virtually everybody in that clip was essentially playing themselves, so we had, I don’t know, sort of a party girl sort of person, and her dodgy boyfriend and all that sort of stuff. They would just usually pop down and Alan Park [who played the pimp] was very handy for us on that sort of stuff because he knew all these people.

Brent Hansen: But my centre always was the closest thing to a performance was best, and if it wasn’t then it was always just going to show the lack of budget; it was a public service. You could go upstairs to the set designers and get an hour conversation maximum and you get whatever they could find and you threw it together. It was never exactly … it was hardly Russell Mulcahy or 16mm auteur-type people. So there was always a bit of a compromise but it got New Zealand music on television and that was a really good thing.

Peter Blake: RWP didn’t have to advertise for bands to appear. I think most bands aspired to appear on the shows as it was obviously a promotional vehicle for them. They made the approach in some instances. Having said that, if there was a band in town or indeed in another city I was visiting on business, I would check them out. I remember going to the Rock Theatre, an alternative venue in Wellington, and seeing Toy Love, who we videotaped in concert there. The support band was a Wellington all-girl group named the Wide Mouthed Frogs. An all-girl band was virtually unheard of in the 70s, and I thought, “what an opportunity.” They were not that musically experienced, so it meant producing a recording at Avalon’s sound studio that could eventually be mimed to. It was a long day and all members insisted on playing their own instruments, still they eventually got it together. The lead singer of that band was Jenny Morris and this track was her first television appearance. But the approaches were mainly from the bands, tour promoters or management which over time got more professional. In my opinion the greatest band manager in New Zealand was a guy called Charley Gray. I’ll never forget him, he was arrogant, obnoxious, aggressive, and that was unusual as most people were too damn nice – maybe band leader Russ le Roq [Russell Crowe] wasn’t. I remember Charley stormed down from Auckland insisting that I be at my desk at a certain time, slammed down a publicity kit including info booklet, professional photos and final mix tapes of a new band he was managing, telling me they would be New Zealand’s greatest. Initially I thought, “this pom is really a pain in the a---.” I played the tapes and couldn’t believe the music. “Okay, Charley, we’re sold.” The band was Th’ Dudes. We immediately launched into making a number of videos for them including the Barbara Gascoigne directed ‘Walking in Light’ and shot some live concerts. They were very much part of our early stable of artists and the rest is history, of course.

Brent Hansen: Peter Blake is a very fair-minded, thoughtful fellow and he was trying to make sure that the greatest possible breadth of New Zealand music got an opportunity, which you wouldn’t necessarily say was true with the overseas contemporary stuff that was coming in. The labels were under pressure trying to get some exposure because obviously things were starting to hone in on us because they had a more commercial world. But if a band came in, there was always the hope that they might get a hit and we could move them across to Ready To Roll. But I think if you were Chris Knox and you were making a video for Radio With Pictures, I think you would probably assume it was only going to go on Radio with Pictures so he was allowed to be more arty and specific. That was the world that he knew was there. But for a lot of people it was still a pipe dream for them that they might get some exposure. Radio wasn’t an issue I don’t think – I mean it was an emotional issue and I think it was wrong that they didn’t want to play New Zealand music.

Liam Ryan: I mean typically we’d release a single like ‘Heart and Soul’ as a radio hit, go on tour and as part of the tour you’d drop in to Avalon, record the clip on a Wednesday and the following Saturday it would be played on RTR or Sunday on Radio With Pictures. There was a kind of a machine there that worked. By the time we got into the second week of the tour – and they were long tours in those days – you were usually charting something massively, and that’s where ‘Heart and Soul’ went straight to around No.4. And then the rest of the tour went on the back of that. So there was a kind of a machinery at work there that was kind of interesting, where the song kind of got traction in its own right on radio and then later on, perhaps a week or two later, you’d be on tour supporting that and then the video would support the tour, so the whole thing gathered momentum. By the time we got to the Aranui pub [in Christchurch] on that tour, we did a Saturday night there and I remember us having $10,000 in cash on the door, $20 a head which was quite a high price at the time and we had 500 people in there and they shut the doors before we went on stage.

Brent Hansen: If I had been handed the money, would I have shot them in the studio? No way. I would have shot them all on location. Of course – why wouldn’t you? I might have shot them in the studio if I thought it suited that kind of band, but I think in general the studio was a terrible compromise. But it was a way of getting stuff done.

--

This is the third in a series of oral-history articles about Radio With Pictures. Dr Lee Borrie teaches art and music history and research at Ara Institute of Canterbury. He completed his PhD in 2007 on the rise of rock and roll and youth culture in the 1950s in the context of Cold War America's containment culture. The bulk of the material used is from interviews conducted as part of a research project examining music video production in New Zealand prior to the establishment of NZ On Air funding.

--

Read Radio With Pictures history 1 - here

Read Radio With Pictures history 2 - here

Read Radio With Pictures history 4 - here

Other sources

Frank Stark, NZ Listener

Michael Higgins (producer), Give It A Whirl TV series

Matthew Bannister, Positively George Street: A personal history of Sneaky Feelings and the Dunedin sound, Reed Books, Auckland, New Zealand.