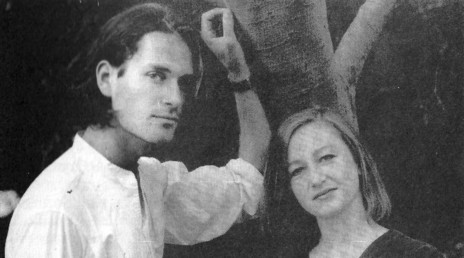

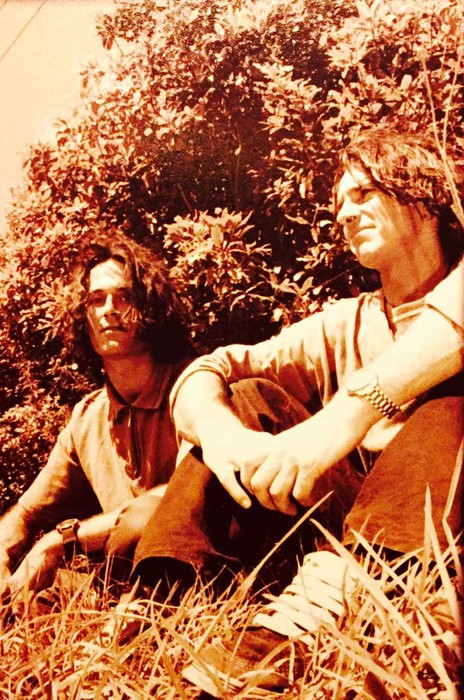

In the 1980s Dunedin’s hill suburbs were a place where you made your own entertainment. Andrew Spittle went to Logan Park High School, and so did I. We started playing some music together and formed a band. The highlight may have been a grandly imploding two-song set at school assembly where a pressganged drummer fled the stage and left the hall after the first song. Andrew fronted the show in aviator shades, a scarf wound around his head and an army surplus shirt. I lurked on bass.

By 1990, school was out. Andrew had settled on a distinctive “swarm of bees” guitar sound, courtesy of a small but loud 40-watt Ross practice amp with inbuilt distortion. A neighbouring friend, Tristan Jamieson, made a Flying V-style electric guitar from scratch and gave it to Andrew. Its large body was reputedly made from a boat rudder. Unreliable wiring was combined with massive dimensions to create uncontrollable feedback.

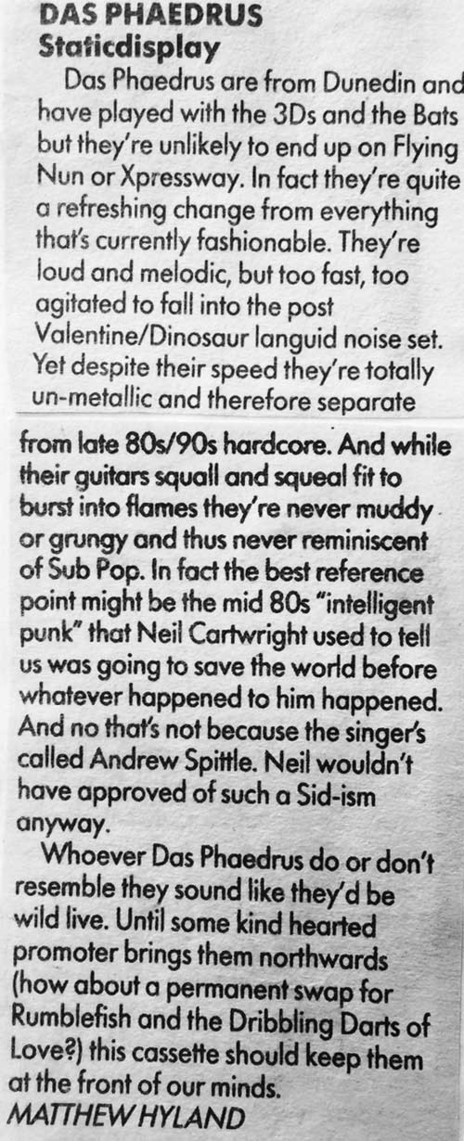

For Andrew, the sound was secondary to the songs. He says his early inspiration was from Hüsker Dü, The Smiths and Nick Cave, and anyone who has heard his music since then will certainly hear ghostly echoes of that sonically diverse trio of musical miserabilists.

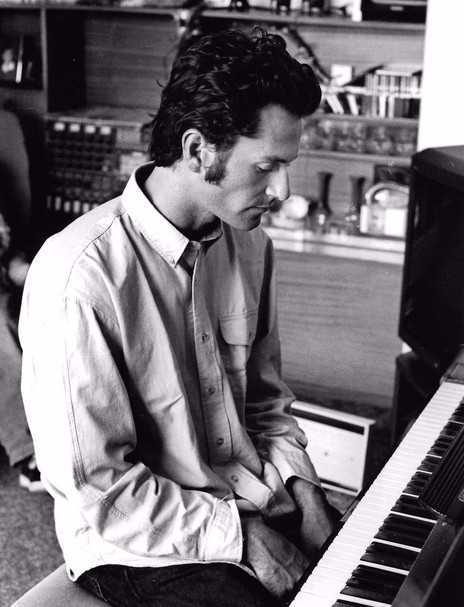

There was no shortage of volume dependent, post punk guitar bands in the local vicinity, but none shared his songwriting method. He was an excellent piano player and would often compose complex songs on that instrument, before transposing them to the guitar, something that he still does today.

A self taught guitarist, Andrew had a style that was simultaneously dextrous and rough and ready.

A self taught guitarist, Andrew had a style that was simultaneously dextrous and rough and ready, all translated through the hectic squall of his midget amp. This all combined with an earnestly literate lyrical style, drawing generously from stage one English Literature papers.

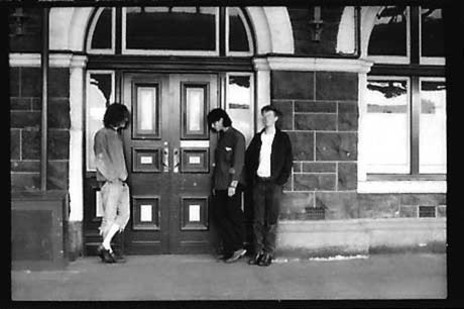

Thrown into university life on the nearby Otago campus, it wasn’t long before the bigger cultural Petri dish led to new developments. I was sitting staring at the wall at the library in the winter of 1990 when Andrew came up and announced he had (literally) found a drummer.

Piers Graham had been practising drums at his Union Street flat, when a face appeared at the window, attracted by the noise. After Piers opened the window to the gesturing stranger, a discussion ensued with Andrew, and a rehearsal time was set up for the new, improved Das Phaedrus.

Even then, Andrew had songs by the bucket load. We rehearsed solidly for a month or two and debuted at a party before playing a show at the Empire Tavern. I collected the door takings, which were quite reasonable. It was the most money I think any of us ever made in the music business. From here on in, it was all losses.

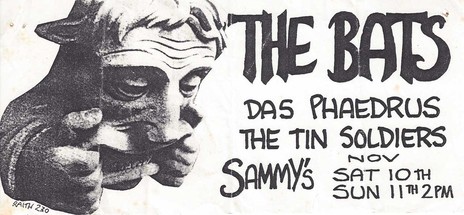

Paul Rose, who was working at Echo Records in Princes Street, set the group up with a support slot for The Bats at Sammy's – along with the (slightly younger) Otago Boys High based group Tin Soldiers, whom we would have more to do with in years to come.

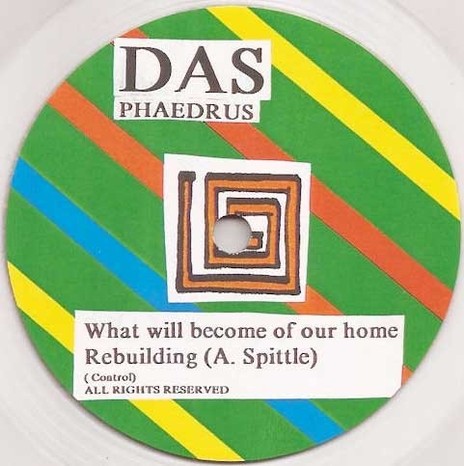

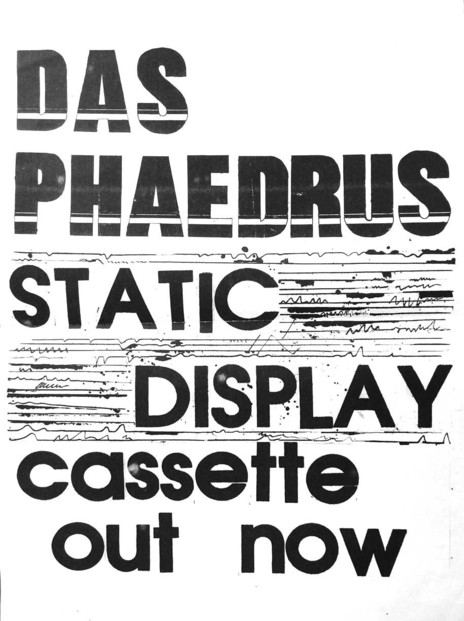

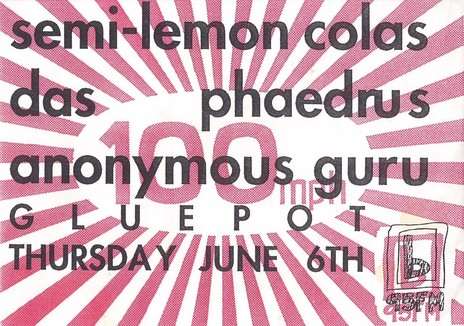

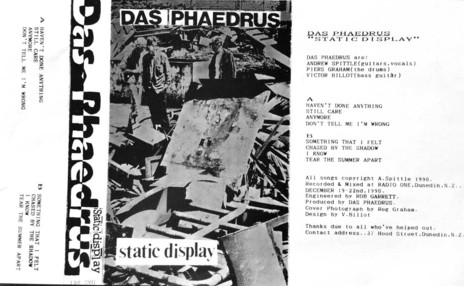

Das Phaedrus recorded a short album, Static Display, at Radio One over the summer and another one early in 1991, and found a practice room the size of a broom cupboard in Vogel Street. We embarked on a tour to Auckland in my Ford Escort, playing at the soon to vanish Gluepot, and at a nightclub in Hamilton where the trusting owner allowed us to sleep on the floor overnight.

Andrew’s single-minded vision and monstrous output of new songs proved too much for me and I soon bailed out, with the dissolution of Das Phaedrus.

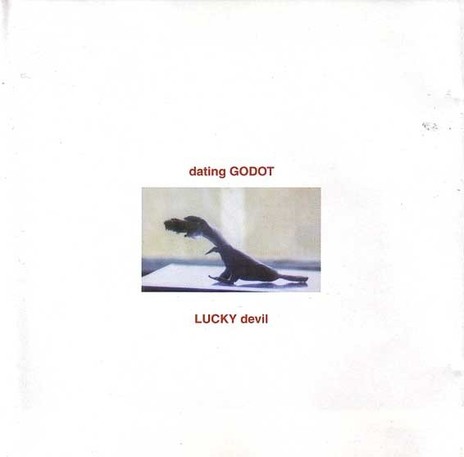

Andrew soon reinvented his musical persona as Dating Godot. He ventured out with bass player Gabrielle Ryan and a drum machine, which was in due course replaced by drummer Robbie Yeats, formerly of The Verlaines and The Dead C.

In true Dunedin fashion, a limited musical gene pool and close rehearsal spaces led to this connection, which as noted by Andrew, was a little unusual in that the collaboration leapt a generation gap in the local scene.

Andrew: “I think it was actually David Mitchell that suggested Robbie. I was down at the Vogel Street [practice] rooms hanging out with [local music group] My Deviant Daughter and we ran into The 3Ds and I mentioned I was looking for a drummer. I rang Robbie up and he turned up at Pioneer Crescent with his drum kit. I played him ‘Frayed’ from Flicker and he liked it. I was pretty excited to end up playing with Robbie, being something of an elder statesman of the Dunedin scene at the ripe old age of 28 – I would have been 19 then.”

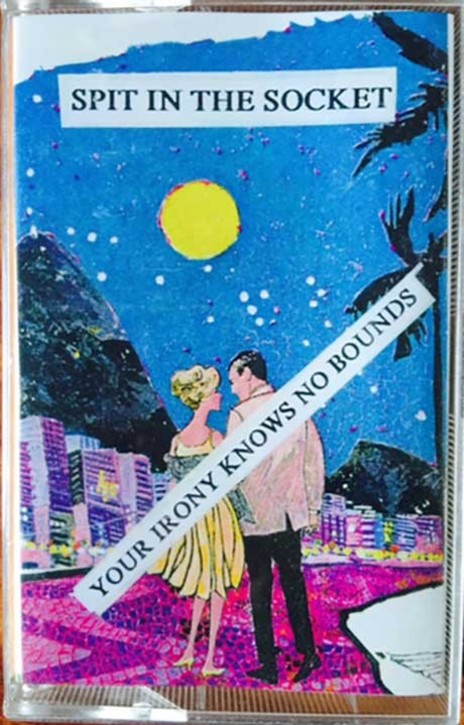

Andrew kept up his rate of recording and very limited run releases, including a number of cassettes and lathe cut albums from Canterbury based King Records.

Rare live performances of Dating Godot tended towards the shambolic: all the individual members were musicians of ability, but appeared to be travelling in parallel directions as opposed to functioning as a unit. But the recording continued, more and more, album after album, rapidly amassing.

Songs lost the frantic hardcore presentation and started to evolve into a more distinctive style.

The group recorded more material at the Spittle family beachfront crib at Ocean View, a quiet village on the coast south of Dunedin.

Andrew completed his studies and briefly relocated to Christchurch and then Wellington, where he recorded at his uncle’s home studio. Gordon Spittle is a well-known musician and writer, and an author of a book on Dunedin’s music history.

A new Dating Godot evolved when Andrew returned to Dunedin, with Piers reappearing as drummer, with Jesse Booher on bass, who also brought recording skills and equipment to the mix. Much of the material on Dating Godot’s first three albums was recorded at this time, at the beach crib.

In 1994, Das Phaedrus briefly reformed and recorded tracks at the short lived Volt Studios (attached to IMD Records) with Brendan Hoffman.

After training as a teacher, Andrew departed for Queenstown and completed a new album in lo-fi style.

After training as a teacher, Andrew departed for Queenstown and completed a new album in lo-fi style on the 4-track of former Tin Soldiers drummer Mark Orbell. He released this and three albums of his previous material on CD format in quick succession via the Delirious label, which he operated in an ostensible partnership with Jason Kerr of the group My Deviant Daughter.

At this time he met Shawn Hardy, an American. They married and later had a daughter.

Andrew relocated to Nelson as a teacher at Nayland College and recorded a series of new albums, with Shawn contributing on bass and new drummer Nigel Duncan creating a new, heavier sound.

At the same time, a much-needed boost to the arrangements and performances of Andrew’s music was delivered by two well-known faces in the independent music scene, one an old friend, and one a new contact in the Nelson music scene.

The first was Jeremy Taylor (formerly of Cinematic), a long time supporter of Andrew’s music, who contributed to recordings with 12-string guitar and vocals, creating some of the strongest Dating Godot tracks, including ‘Debutantes of the World’.

“Jeremy was actually the first and best Das Phaedrus fan. He wrote a letter [in 1990], like a snail mail letter with a stamp and words on paper, enclosing his ten bucks and requesting a copy of Static Display, which he had seen reviewed in RipItUp. He told me he was in a band called Throw.”

The connection firmed up later on. “I got to know him better when I moved to Christchurch. He lived just down the road and I'd see him there at Echo Records, where he worked. He introduced me to the Red House Painters, American Music Club, a bunch of stuff that expanded my horizons a bit. When I moved to Nelson and he had moved to Wellington, he flew over twice for a few days to record Destroyers and I Know Too Much. I had sent him demos of both and he worked out all his parts, harmonies, knew all the lyrics … probably the highlight of my recording career working with Jeezer, so supportive and talented and a rare advocate for quality control in the studio. Probably why those two records are the most palatable. I still keep in touch with Jeremy.”

Initially working with underground legend Dave White as engineer at Nelson’s Artery, Andrew then progressed onto new recordings with Ryan Beehre, a producer and member of the electronica group Minuit.

This brought an entirely new production style to Spittle’s music, using synths, loops and drum machines to great effect on tracks such as ‘For the Bloodhound’.

“That was a mutual decision,” says Andrew of the shift in sound. “Really with Bridle Songs we set out to bring more of Ryan’s background in the electronic stuff to the party. I guess the other stuff we did, before and after, was less that way inclined. Like Jeremy, Ryan was incredibly supportive and far more than an engineer. Very much spiritual advisor, life coach, etc. We had the Wednesday night club every week for a couple of years, where he'd call in for a couple of drinks on his way to his regular covers band gig in town. That was the thing with Ryan. He was an electronics whizz kid with Minuit, but he was also an amazing guitar player. He actually played on a couple of tracks on the Kamikaze album. It was nice on that song ‘Under Volcano Fields’ to pay tribute to some of those guys – Robbie, Jeremy, Ryan.”

After his marriage ended, Andrew stayed in Nelson, continuing to record. As a live entity, it was pretty much the end of the line for Dating Godot.

His strength lay in recording rather than the live rock and roll circuit, as he candidly admits.

His strength lay in recording rather than the live rock and roll circuit, as he candidly admits. “I always sucked live – apart from in the old days with Das Phaedrus. Dating Godot with Robbie and Gabrielle was a bit of a shambles. The last time I played with a band was 2001 in Nelson with Nigel and Sally. That was really good, but I had this terrible migraine and walked off stage at the end and went home and basically never saw Nigel again, which makes me sad.”

After Nigel Duncan’s departure, Aaron Plimmer stepped in on drums.

In 2004, Andrew and partner Sally Lonie relocated north to the remote Northland township of Taipa. The shift also signalled a new beginning artistically, as the Dating Godot name was retired in favour of All Red Cables, under which name he has recorded and released since that time.

Andrew continued to record, travelling to the Whangarei’s Big Door Studios, where he has been recorded by producer/ engineer Brendon White, and joined on drums by Clint Thoms. He has returned there ever since, even after moving to Hamilton in 2006, producing albums often with a more stripped back, acoustic approach.

Up until 2010, Andrew continued to release music at a steady rate of one or two albums a year. He then stopped recording music for several years, but engaged in other pursuits, including writing two (as yet unpublished) novels. 2015 saw a new album, and the release online of both two retrospective compilations of his music spanning 20 years (1990–2000, 2000–2010).

Andrew has also re-released most of his recordings in digital format, under the All Red Cables name, making them accessible to a wider audience for the first time ever.

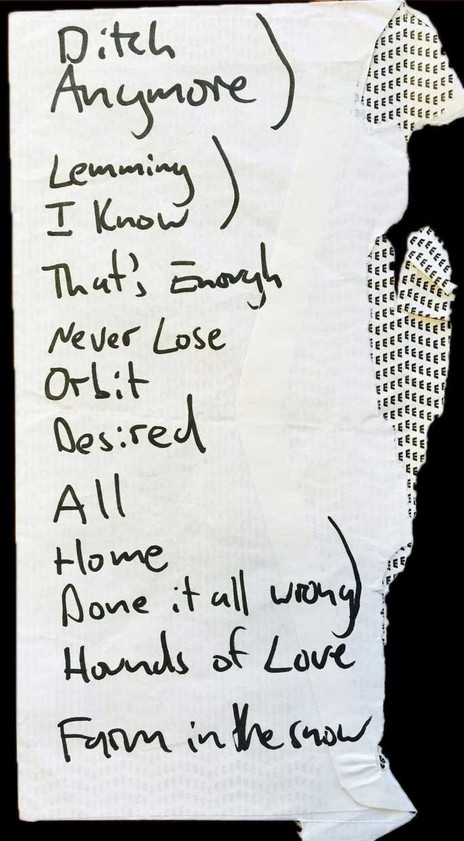

One of the most interesting aspects of Andrew’s career is the vast recorded output. The high water mark was 2000, with the recording and limited CD release of five albums and an EP in one year.

The positive or negative, depending on your perspective, is that this leads to a wide continuum of production values. Despite the complex nature of his songs, musically and lyrically, Andrew has always smashed out records in a series of one-take frenzies and late night mixdowns.

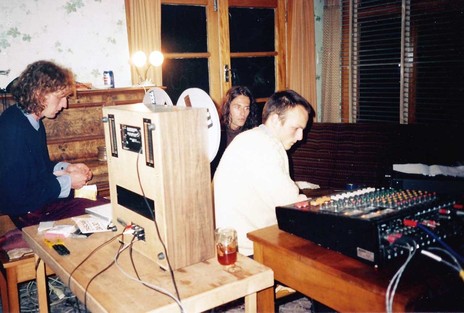

“They've all been pretty fast,” he says about his recording methodology. “Working with Brendon [White] in Whangarei, I'd drive up from Hamilton and we'd start around midday, work through and have the whole thing done and mixed by midnight. Certainly Ocean View, Pirate Heaven, Time Together were like that. Other albums have been two or three missions like that put together, three or four tracks at a time. I guess the most truly epic session I did was with Robbie [Yeats], Gabrielle [Ryan] and [sound engineer] Richard Baker at the beach house in 1992.

“We hired a 4-track reel to reel, and disappeared for three days with a lot of beer and equipment and 26 songs to record. That was harder because we were setting up a studio from scratch at the same time. It almost killed us. But I've got used to the hectic pace – for me, it's part of the buzz. I think Zen Arcade [Hüsker Dü album] kind of validated that approach, although my detractors would argue the music has suffered as a result. I don't know if that's true. Pig Hunt was pretty mental. That was 15 songs in one night with Nigel Duncan and Dave White. At least we mixed it the following night. Often it's the mixing, rather than the performances that suffer when you work fast.”

Andrew rarely plays live and has never performed outside New Zealand, a situation that seems to be unlikely to change in the near future.

“The last acoustic show I did was opening for Mark Kozelek [Red House Painters] in 2008, which Jeremy [Taylor] set up for me. I was so excited, but sadly it was soul crushingly bad. He's a pretty tall act to go head to head with in an acoustic guitar duel. I was nervous … it just didn't work. So I don't have plans for live stuff at the moment. Playing live with a band has greater appeal. I have zero profile in Hamilton, so I'm hardly going to turn up with an acoustic guitar and subject myself to social and artistic death in front of a handful of Waikato humans.”

Despite this blunt assessment of prospects on the local scene, there is no sign of creative implosion. Andrew says he is considering more recordings, albeit on a less zealous schedule.

“I'm pleased I did Time Together (2015) ‘cause it had been a long time, five years, and the lack of any music was making me feel like I was just tilting towards old age and certain death. I had spent that time trying to write novels, but that was getting frustrating and insular as well. I'm sure I will continue to do stuff, but not at the breakneck speed of old. Maybe one batch of new songs every couple of years, when I feel the need, something like that.”

Looking back, he says he prefers the “more idiosyncratic ones” in his back catalogue – “Pig Hunt, Pirate Heaven, Hated By Girls. But I can appreciate they don't offer the easiest pathway in.”

“In a way, I guess my favourite is Hamilton Jet, the acoustic one. I did that when I picked myself up off the floor after the Mark Kozelek support debacle, and I'm pretty proud of that one as a guitar and voice thing. I think my favourite ever song is ‘From a Transcript Undercover’. It has a can-do attitude and nothing – not loss, not death – will stop its cheeky protagonist. It has a real punk sentiment, despite sounding like something off After the Goldrush. A lot of folks seem to think Granity Mill is the best [album], the most coherent. Maybe they're right. When I say a lot of folks, I mean a couple.”

In terms of finding the easiest pathway into his music, he considers the double album digital compilation of 20 years of work he released in 2015 to be “a pretty solid artefact”.

Living in a state of internal exile, Andrew Spittle is a perennial musical outsider, driven by compulsive creative demons. What makes him stand out is his remarkable level of output, almost wilful invisibility, and a coherent artistic and musical vision that only becomes apparent after considering his entire body of work, which manages to be all at once flawed, ambivalent and grand in its scope.

His songs and lyrics could only have come from New Zealand, but they are really the product of an interior world: simultaneously self-obsessed, world-weary and wielding a sometimes devastating insight.