AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

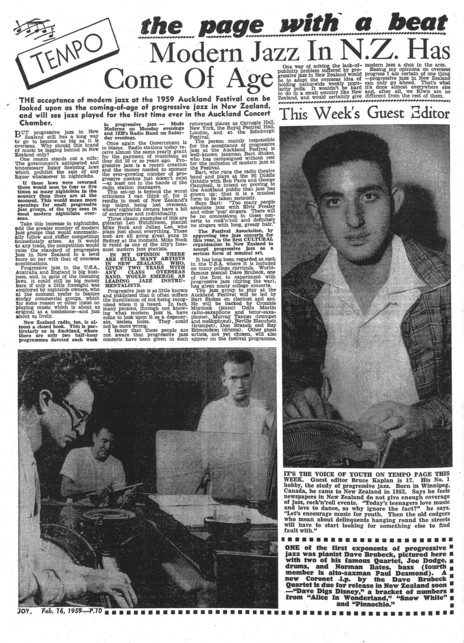

Bruce Kaplan

By day, he was a teenage cub reporter on the Auckland Star; by night a crew-cutted, jug-eared music fan and fly-on the-wall at “nitespots” like Auckland’s pulsating Jive Centre and its Picasso jazz basement, hangout of the beatniks.

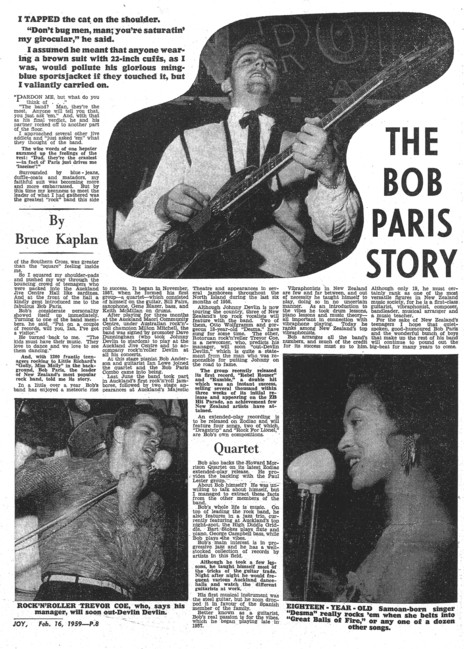

Kaplan’s cool-cat themed piece from 1959, about rock’n’roll guitar hero Bob Paris and his band wowing slick-backed audiences, remains a classic of its kind:

I tapped the cat on the shoulder.

“Don’t bug me man; you’re saturating my girocular,” he said.

I assumed he meant that anyone wearing a brown suit with 22-inch cuffs, as I was, would pollute his glorious ming-blue sports jacket if they touched it, but I valiantly carried on.

I approached several other jive addicts and “just asked ‘em” what they thought of the band.

The wise words of one hepster summed up the feelings of the rest: Dad, they’re the craziest – in fact ol’ Paris just drives me ‘inseine’.”

Kaplan’s Jive Centre report was one in a series published in music weekly Joy, about Auckland’s ‘cool’ music and fashion scene, with its American hipster lingo.

He depicted the Hobson Street venue as the place “where 1200 enthusiasts rock every weekend”, the venue where the “squares were helped to change their shape”.

“… the first New Zealand all-jive dance hit Auckland with an impact that the city won’t forget for some time to come. The venue … was packed to the seams till the cats were ‘crawling up the walls’.”

In his column he thundered that local newspapers failed to give enough coverage to today’s music: rock’n’roll and jazz.

During Kaplan’s moonlight stint with Joy, the 17-year-old guest contributed to its Tempo page as a guest editor. In his column he thundered that local newspapers failed to give enough coverage to today’s music: rock’n’roll and jazz. “Today’s teenagers love music and love to dance, so why ignore the facts? Let’s encourage music for youth. Then the old codgers who moan about delinquents hanging round the streets will have to start looking for something else to find fault with.”

Kaplan’s relationship with the music weekly, however, ended in tears, as he explained in an interview with Chris Bourke half a century later. “As a stroppy young man I wasn’t paid on time for an article. I phoned a couple of times and nothing happened.

“So I sent a letter, typed it out. It said, ‘I’ve asked three times for my money but you haven’t paid me. If this money is not paid within seven days, I should have written my last article for Joy’. I got a letter back saying ‘Dear Mr Kaplan, your cheque is enclosed, and by the way you have written your last article for Joy’.”

Kaplan would always have itchy feet. Hailing from Canada, his parents arrived in 1952, when he was 10, the family living in Mt Albert. He attended Avondale College, part of a jazz-loving generation whose world was upended in 1956 when Rock Around the Clock, with its brief but indelible performance by Bill Haley, screened locally.

And it was at Avondale that he first met an older pupil: jazz fan and music maestro Bob Paris, who by 1959 was a dominant force in both musical styles. Paris spent half of his time driving teen rockers wild at the Jive Centre with his guitar playing; the other playing vibes with a progressive jazz trio at the Picasso.

Kaplan recalled the beatnik crowd: “It was up somewhere behind the Town Hall, always crowded, it was a buzz, you had to queue to get in. It was an eclectic mix; a gay scene but also duffle coat territory. It was a place to be, it was a place to meet a girl or guy. But by god it was popular.

”I went along to watch Bob Paris perform there with a jazz trio, with talent head and shoulders above the rest. Bob was a pragmatist who embraced rock’n’roll but his real love was jazz.”

Kaplan also elbowed his way into our first tour by overseas rock’n’roll acts – the mythical 1959 visit of Gene Vincent and Johnny Cash. He met Vincent but has fonder memories of the “man in black”: “Here’s me, a young guy and Cash put aside maybe two hours of his time to talk to me. He was staying in a hotel with a bed too short for him on the corner of Shortland and Queen Streets. He was pretty unimpressed with it all, but said ‘come on down, let’s have a drink’. He didn’t have to do that, and he certainly didn’t need the publicity. He was great.”

Kaplan quit New Zealand as the 1960s arrived, briefly setting journalism aside for more strenuous work on oil tankers (after which he spent a relaxing year in Rarotonga). “I was always a roamer.” In 1964 he returned to Auckland and – with Joy long defunct – got a reporting job on the notorious weekly Truth.

He recalls the Queen City as eerily quiet: “If you wanted to eat on a Sunday in Queen Street, you could starve to death before you could find anywhere open. It was terrible. The pubs closed at 6pm; there was the feeling that Sodom and Gomorrah would take over if people drank until 10 at night.”

And young people faced incredible pressure to conform. “The look was conservative. You’d have your sports jacket, comb your hair and put on your probably one good pair of strides. The women would dress up nicely and it was all incredibly formal. You were still getting dressed up to go out.”

His features on the Jive Centre and Bob Paris meant he got close to the pioneering promoter Dave Dunningham.

New Zealand’s rock’n’roll scene was in its infancy. His features on the Jive Centre and Bob Paris meant he got close to the pioneering promoter Dave Dunningham, who ran the Jive Centre on Hobson Street and Surfside on the North Shore. Kaplan decided to give promotion a try, and asked Dunningham if he could book one of his top acts – Dinah Lee – for a dance in Papatoetoe. He put enormous energy into promotion, and had the hall booked out, but no confirmation from Lee. Forty years on, the memory still rankled; Kaplan was certain Dunningham led him up the garden path. A few days out from the gig, he realised he had no lead act. To save his shirt, he phoned Paris and called in a favour. “I said Bob, I’m in a real hole … he got his whole band out there on virtually no notice whatsoever and gave this fantastic concert. I warned the public in advance. I think Mike Nock was in the band.

“But Bob really bailed me out after Dunningham had beautifully shafted me, stopping me honing in on his territory. I don’t blame him, I was pretty naïve. I still made money out of it but I never tried anything again. I thought this isn’t for me.” Dunningham was “a tough operator, a wheeler-dealer, who always treated me well except for that episode.”

Phil Warren, on the other hand, “was just terrific. You could shoot the breeze with Phil and – tell you what – Phil always kept his word. A very likeable guy with a good reputation.” Warren was a music person, whereas with his competitor Harry Miller, it was “the hustle” he enjoyed. “Harry was about money – and that’s not a crime – I’m just saying Phil was driven by deeper motives I think.”

Kaplan enjoyed seeing Ricky May at the Picasso – “he arrived fully formed, he was head and shoulders above the others” – and Freddie Keil and the Keil Isles at the Orange (“a very classy rock group, who used to do a lot of Chuck Berry covers”). Another Auckland venue Kaplan recalls is the Embers, a central city club run by English expat and folk singer, Nick Villard. “It was extremely popular, we’d all go in there and, no matter what the weather was, we all had duffle coats on, with bottles of grog inside: scotch, gin or vodka. Everyone would sit all night ordering vast quantities of Coca-Cola. It was just … tragic really.”

Although rock’n’roll created a kind of moral panic among parents, and the Trades Hall/Jive Centre could be a “rough joint”, they were innocent times. A few musicians dabbled in pot or amphetamines in the early 1960s, but not Kaplan. The closest he got to a den of iniquity as a Truth reporter was Gleeson’s Hotel, an early opening/late closing pub on the waterfront, where men drank out of jam jars while sitting on crates, and on the rare occasions it shut, after-hours sales were always available.

He got friendly with all kinds of musicians, regularly going swimming with pop duo Bill & Boyd at the Point Erin baths, and also mingling with Bob Gillett, the US-born jazz saxophonist and arranger who settled in Auckland in the 1960s. “Whenever I would go round [to Gillett’s] there would be some jazz musician picking his brains or jamming with him. He was incredibly skilled and talented and he came out of the American jazz school. He was held in high esteem.”

By his early 20s, Kaplan was still in love with the music, especially the rhythm and blues pouring out of Britain: long-haired crews like the Rolling Stones, the Animals and the Pretty Things. The smiling Beatles were kind of ... square.

And when the infamous ’Things flew into New Zealand on a package tour with Sandie Shaw and Eden Kane in 1965, Kaplan was ready to use Truth as a vehicle for the hell-raising bad boys of rock. (See accompanying story, Fake News and The Pretty Things.)

Kaplan was then snapped up as entertainment reporter by Sunday News, the country’s first Sunday and a tough-minded paper keen to make its mark. He was sent out to spy on world famous opera diva Elizabeth Schwarzkopf after Sunday News editors dreamed up a story that her cold might ruin her Auckland Town Hall concert. It didn’t. He ended up being charmed by her.

“I’d gone from jazz and rock to doing ‘the show must go on’ interview with one of the world’s truly great opera singers, a gracious lady. It’s always part of the fun of being a journalist you know you just never know what’s going to happen or who you might run into.”

Kaplan left New Zealand in 1967, and worked for several years in Singapore until he and several other journalists were expelled from the country after their proprietor fell out with the hardline prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew. Since 1972 he has lived in Australia, based mostly in Melbourne. His love of music remains but the thrill of writing about it, born in the cauldron of 1950s New Zealand rock’n’roll, has gone.

“I did a terrific interview with Bette Midler about women’s rights, all kinds of fascinating stuff. At some stage she said she liked Australia. It was then rewritten with the intro ‘Bette Midler – I want to live in Australia’. I could have wept at the imbecility, the sheer rubbish you know: here they had an intelligent interview with an intelligent person and they'd reduced it to Sunday drivel.”

--

Kaplan on Paris - the Bob Paris story

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air