Anyone who knows Jim Hall – composer, arranger, songwriter, business owner – knows he is a man of many parts. He is personable, multi-skilled, has a wry, sardonic wit, and knife-edge intelligence.

His life to date has been thick with detail, of national and international professional music experiences, social and business interchange, and creative collaborations and achievement. His anecdotes range from hilarious and spiced with the odd snide comment to tender, especially where his family, past and present, is concerned. His own passions – golf, performance vehicles, Formula One, boats, fishing and so on – take a close but second place.

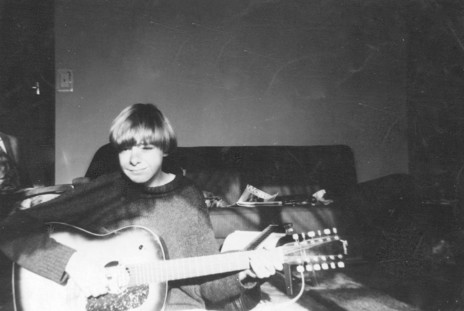

Jim Hall with his Framus Hootenanny 12-string guitar, circa 1966. - Jim Hall Collection

I first met Jim at the University of Canterbury in the late 60s; we were part of an arty group from various disciplines. He was one of the musically gifted among us with spidery fingers that could straddle electric, acoustic or nylon-string fretboards easily and negotiate piano or organ keys equally well.

He had a mental storehouse of many different styles, had taught himself to read music, and was already playing professionally by the time he finished high school. But apart from a few piano lessons he was limited in the classical music area. Nevertheless, he had signed up for a Bachelor of Music, the only serious course available (Jazz School did not exist then) for someone of musical potential – and Jim had more than most, as the years have proven.

“I was a stranger in a strange land,” he says. “Ultimately, it was a place for people to become a music teacher; that was the beginning and end of it. Every kind of music I liked – pop music, film music, jazz and any form of popular classical music – was either discouraged or totally avoided. It was a bastion of old-fashioned, academic dinosaurs. But a few people stood out, for instance [composer] Dorothy Buchanan, the late Murray Wood was there for a while, and so was Stu Buchanan.”

For Jim, the degree was a quick path to the technical heart of music, “learning about a musical style that I didn’t quite understand and the language of orchestral music, especially”.

“At the same time, through [drummer and pianist] Harry Voice and others I was getting into jazz and other things, and learning as much from that as from music school. I only went to university in the first place because my mum, who would have preferred me to be a doctor, would’ve been distraught if I hadn’t done a ‘proper’ job.”

When I caught up with Jim recently it was only the second time in about 50 years. He is the same Jim, except that over those decades he has amassed a truckload of career highlights and enough awards to paper his studio.

Apart from his native musical ability, some of his success in the creative industries has been down to his ability to recognise trends and stay ahead of the game. The “tinkering” gene he shared with his father has engendered an ability to experiment and innovate. At Soundtrax, the company he founded with Steve Robinson in Wellington in 1984, he rode the first Internet wave in New Zealand.

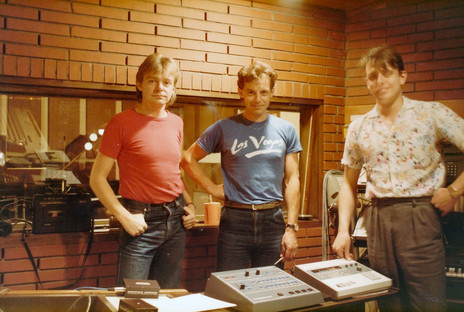

Jim Hall, Steve Robinson, Ian Morris at Marmalade Studios circa 1984. - Jim Hall Collection

“The minute that home computers came out I had a TRS80. I taught myself to write basic language and did a course in digital electronics. I never wanted to be behind the eight ball.”

Tech widgets and gizmos still make it into most corners of his life. “I do it with golf, too. I’m terrible [at it], but I have little sensors on my clubs and when I get back home my whole round appears on a map on my computer.”

Back in pre-digital days, the process of recording audio was intensive and often frustrating process. It is still intensive, but digitisation has many inbuilt shortcuts.

“To record anything, you needed a studio with a multi-track tape recorder that had to be aligned every morning, and tape was expensive. I have done a demo on a mark #1 iPad on a plane since and got it through, but that was at the end of my serious career and the beginning of computers.”

One of the early Soundtrax ads was for the launch of Lotto in New Zealand in 1987. A bit like a sequence from an old movie it featured a large troupe of dancers doing a Busby Berkley-esque routine to a remake of the song, ‘We’re in the Money’. His timely (and expensive) investment in a Fairlight CMI aided in the complex process of re-recording sections of it every time there was a change.

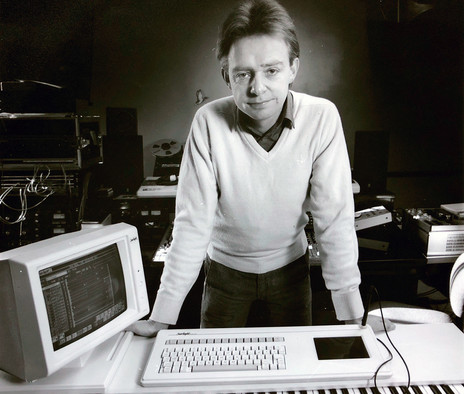

Jim Hall with the brand-new Fairlight CMI III, Soundtrax, Wellington 1988. - Jim Hall Collection

“It was shot and edited on film and recorded on tape,” Jim says. “We’d only just got the Fairlight. People thought that when we got that, everything was going to sound electronic. In fact, all the drums are Fairlight, because we were constantly having to change it, and on tape that meant you had to re-record everything. Now, you can change things in Pro Tools very quickly.

“In another country all of us would’ve been in the music industry, making records, producing artists, but in New Zealand then that was totally impossible. With no internet, there was no way you could be Lorde and three months later be picked up in America. There was no avenue for that to happen, no matter how good you were. Whatever you did as a record guaranteed that you were always going to stay in a low socio-economic bracket. It was pointless. You were just knocking your head against a brick wall.

“That’s how I, Steve Robinson and Ian Morris got into advertising. We were all way over-equipped when we started doing it. And, really, within a year of starting we were away.”

No sooner would they finish a stereo mix of a final product for a client than they were loading another 10½ inch reel for a job they had to finish the same day.

“It was an insane turnover of stuff. For the first three-quarters of the ’80s, sometimes we’d just do a job and send it. Someone would ring up and say, ‘I can’t quite understand the second-to-last word’. Nowadays, someone might ring and say, ‘There’s a note at seven seconds and we’re wondering what that would be like at the start’. There’s almost no emotional response to anything now – everything has just become a one and a zero.”

Soundtrax, both in Wellington and again after its move to Auckland, was acknowledged regularly by the industry with repeat orders and annual national and international awards.

“People think that we were really successful because we couldn’t be pigeonholed. I would make up a showreel and it would be so diverse, but now you can’t do that, because people just don’t trust versatility.”

Jim cites an experience he had after winning a Gold Clio for the sensuous, atmospheric French song he wrote for a Robert Harris coffee ad. After he had collected the award at the Leonard Bernstein Theatre in New York and been played onstage by Toots and the Maytals playing his tune he was introduced to top admen from the four biggest New York agencies.

“The award I’d won was for FCB New Zealand and I remember going into FCB, which was almost a block of Manhattan. I had my reel with me, so we ran it and at the end of it the head of TV, says, ‘That’s an amazing reel, man. Who does your music?’ And I say, ‘I do the music.’ And he says, ‘But who does those American Songbook kind of things?’ and I go, ‘I do those.’ ‘But,’ he says, ‘who does the kind of electronica stuff?’ I say, ‘I do that.’

“And I looked at his eyes and they said: ‘Liar!’ Because in New York, if you want something that sounds like it’s from the Great American Songbook you go to your man on 48th Street, and if you want electronica you go to those two dweeby guys up the road, but if you adopted specialisation here you had to have a day job.”

At Soundtrax they needed many skills overlaying the prime requisite of a keen musical ear in order to command the multitude of tempos and visual story-telling styles that agencies used for their clients’ products.

“In the early days, Steve Robinson would play drums and I would play guitar or bass, and then the two of us would swap instruments and record another lot. It’s easier to do that now with Pro Tools or Logic – you just rip through it and if you make a mistake you can fix it. On tape, you really do get good at not making mistakes.”

For the “re-imagined” Vivaldi Four Seasons compositions Jim wrote the music for the National Bank’s black stallion ads in the early 2000s, his orchestration skills came to the fore.

“The National Bank brand was huge in New Zealand. Before it ended overnight when the ANZ bought it, it was a kind of a treasured brand. I remember for the last Vivaldi session we were in York Street Studios, which was the rock ’n’ roll studio. The last time I’d been in there was recording The Feelers singing ‘Right Here, Right Now’ for the Rugby World Cup.

Recording Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for the National Bank TVC, York Street Recording Studios, Auckland, c 2007; the conductor is Peter Scholes. - Jim Hall Collection

“We had a crack 20-piece orchestra from the NZSO and I had Peter Scholes conducting, because my conducting is appalling, and we were trying not to do it to click tracks. I had everything clicked if need be, so if I had to push the red panic button we could go to click tracks, but were trying to get them as performances and Peter’s really good at that. You’d say, ‘That was 46 seconds and it needs to be 45’. He would get the tempo up and we’d get the performances.

“We were kind of doing an ‘Eleanor Rigby’; we had everything close-miked, so it sounded larger than life, edgy, and you could hear the rosin. When it comes down to it … your expectations have to be higher than the listening public. The Wellington agency was Chris Martin and Hugh Walsh, old-school advertising people and old friends, and Chris said, ‘We should soak this up. This is the kind of thing that may never happen again.’ He was very prophetic.”

One thing that stood out during the course of this conversation as Jim talked, was that he is not one to do anything by halves. If there’s something that grabs his interest, he will pursue it to the nth degree. “I don’t know how to not do it,” he says.

Take sailing, for example. He couldn’t put his head under water until he was 30, and then not till he had some swimming lessons. After managing to get his head under, he didn’t stop there. “All of a sudden it empowered me and I thought, ‘I wonder what it’s like sailing a boat’.” Six months later he was out on Cook Strait.

And at one time he won the New Zealand radio-controlled cars championship, but now he races against other Formula One buffs through the iRacing portal. Anyone can sign on, but you have to earn a licence by proving your racing skills. His most recent success on the “track” won him tickets to Wimbledon.

Jim Hall with the yellow car at the final of the 1979 NZ Radio Control Grand Prix. - Jim Hall Collection

“It’s incredibly well monitored. If you are in decent fields and everyone’s right around you, wheel to wheel, no-one wants to see cars flying in the air or anything. Everyone’s driving as though they’ve taken a mortgage out on their house for the car they’re driving.”

Not taking risks is possibly the opposite of Jim’s career trajectory, but hair-raising as some of his business steps might have been, they have all proven worthwhile.

“I didn’t have a lot of choice about moving to Auckland. I’d freeholded my house and had that amount of financial independence, but not much else in Wellington. The last year of running business there I was on planes all the time, and a couple of plane flights takes any money out of a job. It was disruptive and not good for the kids. Sometimes in the end you’ve just gotta do it.”