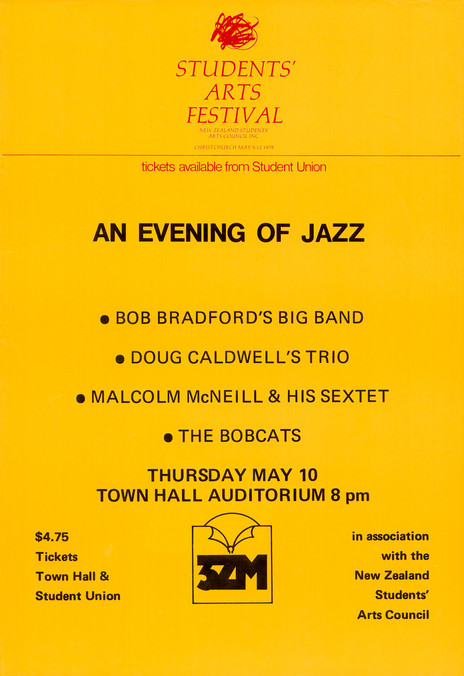

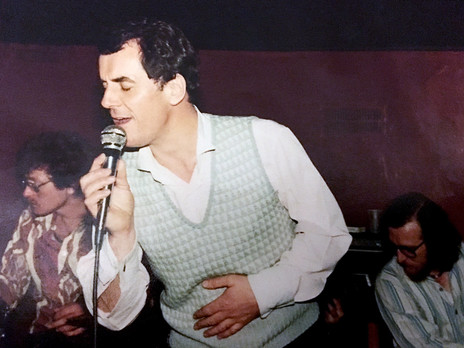

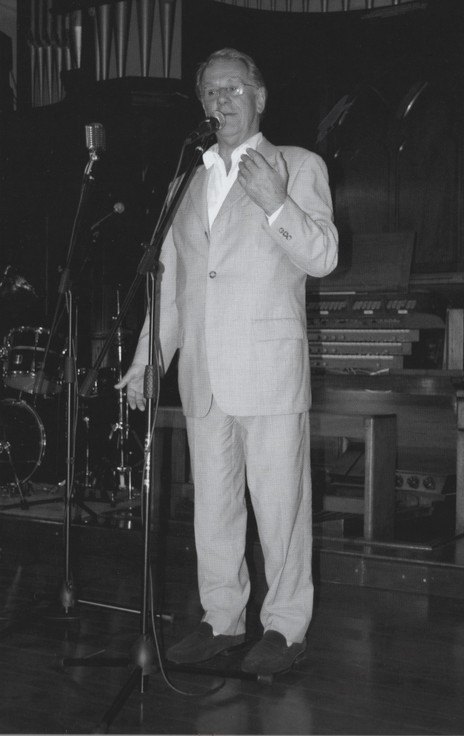

We spoke in Christchurch in early 2024 and he talked of jazz and arts festival performances; of concert, club, studio, broadcasting and international stage appearances with small ensembles or symphony orchestras, from New Zealand to London, Nice to the Netherlands, New York to Japan, Sydney and Paris to Ghana.

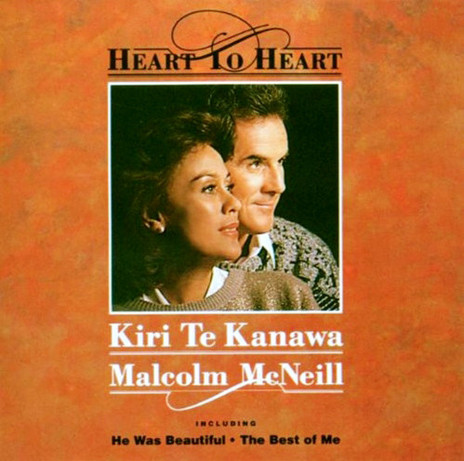

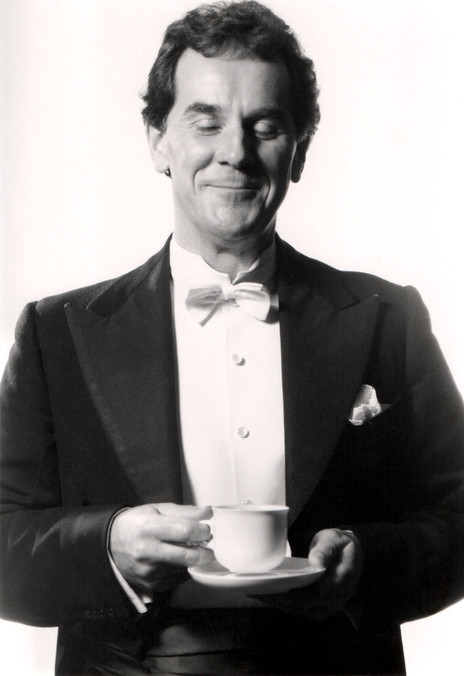

Along the way he amassed a loyal fan base, appeared some 70 times with the NZSO, and recorded nine albums, including the US Billboard-charting Heart to Heart duets album with Dame Kiri Te Kanawa. He also topped the charts in Japan and Australia with the single, ‘Melissa’ (written for his then wife), from his Songdance album.

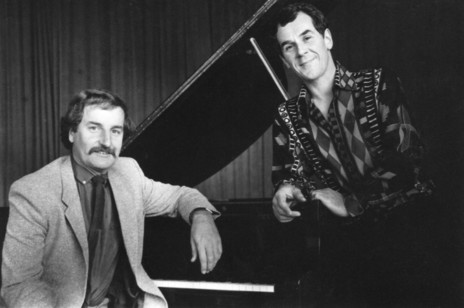

McNeill worked with and promoted other artists. He performed with the country’s jazz best – Julian Lee, Doug Caldwell, Rodger Fox, Mike Nock, and Dave Fraser, among many others – and was based in London for six years where he was lead tenor with vocal septet the Mike Sammes Singers. He worked in the UK, Europe, Australia and New Zealand with jazz royalty: the conductor and musical arranger Sir John Dankworth and wife, singer Dame Cleo Laine.

The Dankworths said of him: “[He was] one of our all-time favourite singers … one of the truly great practitioners of that increasingly rare art – singing quality songs as they should be sung.” Reputedly tough American critic Rex Reed wrote, after hearing him perform in New York: “He has sophistication and an intimate way with lyrics that is hard to surpass.”

Long before all the accolades and encores, Malcolm Ivan McNeill was born in Christchurch in 1945, and raised there. He scratched away at violin lessons as a boy and sang with his pitch-perfect sister Trish and friend at the evangelical church the family attended. There, devotional fervour sometimes rang with hints of Southern White-Baptist gospel, perhaps nudging his subconsciousness jazz-wise.

In those pre-TV days, when a Friday night family outing was going to Begg’s music store to hear its pianist play tunes from the latest sheet music, musical gatherings were commonplace in homes, and McNeill’s pianist mother played the hymns and popular songs for theirs.

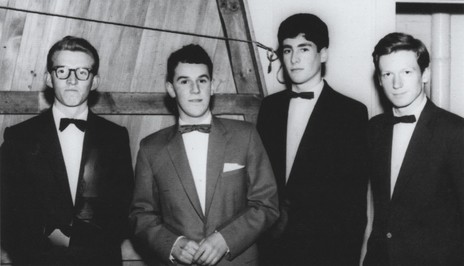

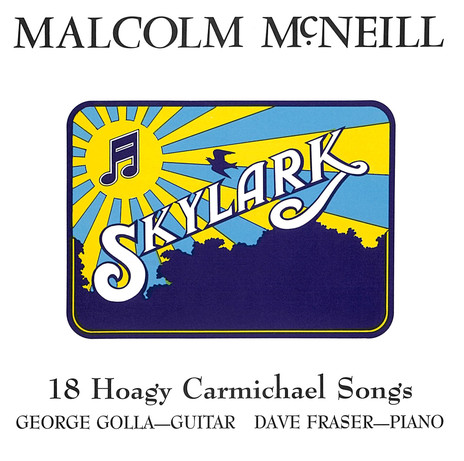

Later, at Christchurch Boys’ High School, where he enjoyed sparky rapport with his best mates David McPhail (actor-comedian) and Ken Ellis (writer-broadcaster), his taste in music started veered away tangentially from the choices of choirmaster Clifton Cook. By night he and older brother John would tune John’s crystal set to Australian broadcaster Arch McKirdy’s jazz programme on ABC radio, and songs and tunes from the likes of Duke Ellington, Cole Porter, Hoagy Carmichael, George Gershwin, and Mel Tormé lit a fire in him.

“I’d cycle through Hagley Park to school, singing ...”

He absorbed the songs osmotically, he says. “They came into the body without my having to think about it. I’d cycle through Hagley Park to school, singing in my head with a scarf around my mouth. I had a facility to improvise early. I could sort of scat sing and feel or intuit the harmonic changes.”

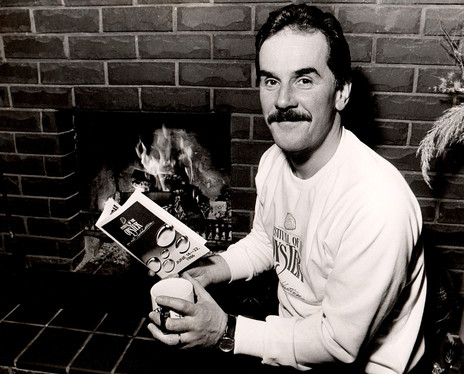

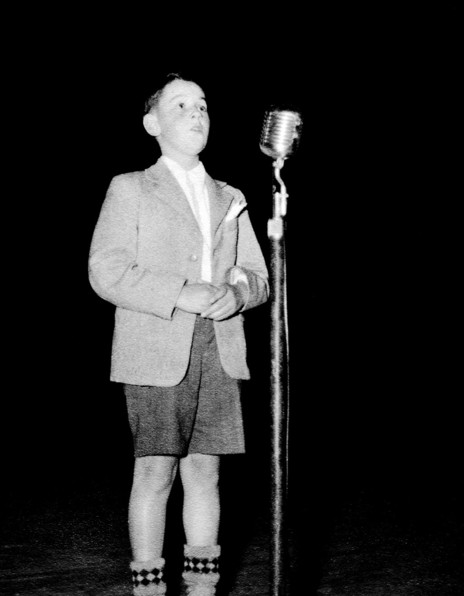

The passion was building and in his mid-teens he answered an advertisement by pianist Graeme Cooper seeking a singer for a new restaurant at Christchurch International Airport. He turned up to audition in his school-uniform short pants, sang ‘Lullaby of Birdland’ and landed the job, his first pro gig. Every Saturday he would sing in a suit of John’s and delight in his secret life outside of high school.

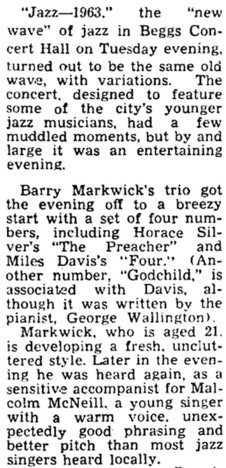

Back then, radio was king and to be on air was a realisable ambition. McNeill’s initial step towards this was, unexpectedly, through school. His history teacher was Pat Vincent, a former All Blacks captain and jazz vocalist. Vincent recognised his talent and introduced him to well-known national radio and bandstand pianist Doug Caldwell, who would become one of his favourite pianists and a musical mentor. McNeill would soon be among singers Vincent, Zarlene Todd and others, performing with Caldwell’s trio at the popular Malando, Christchurch’s first licensed restaurant (it opened in 1952).

The Malando was around the corner from the town hall and many of the international artists appearing there were post-show diners. When tipped that the Oscar Peterson Trio would be in for a meal one night, Caldwell wrote later, “that set the nerves rattling” (My Life in the Key of Jazz, CPIT, 2010). The trio dined there on each of their three nights in town, sitting in with the band, thoroughly enjoying themselves, a huge Peterson “half-wrecking the dainty piano”, according to Caldwell.

This was a rarefied atmosphere for someone in the early stages of a music career, but a closer example of the jazz life was just over the back fence from the McNeill’s house. Their neighbour was singer Coral Cummins, well-known on the national circuit. Her home was another hub for touring artists, including the Dave Brubeck Quartet and the Modern Jazz Quartet. McNeill met these musicians there, but one individual proved more directly important for him. This was esteemed pianist, producer, arranger and multi-instrumentalist Julian “Golden Ears” Lee. Blind from birth, Dunedin-born Lee was as influential as any other jazz musician of universal renown, and over the course of his career he worked with countless international artists, especially in Los Angeles, where he’d been summoned to work by Frank Sinatra.

Julian Lee turned to McNeill and said, “Sing, boy, sing”. So ordered, he sang.

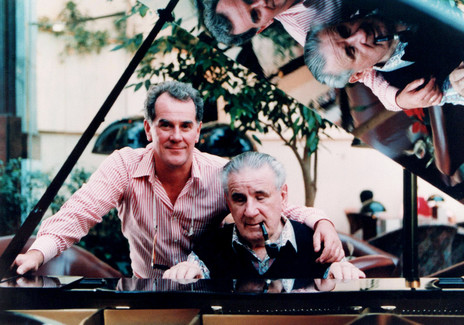

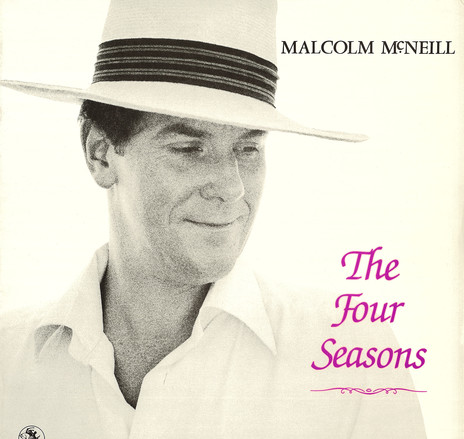

At one point in the evening Lee turned to McNeill and said, “Sing, boy, sing”. So ordered, he sang, and this was the beginning of their friendship and working relationship, with concerts and studio work in New Zealand and in Australia, where they recorded McNeill’s The Four Seasons album with the ABC orchestra.

After high school, McNeill drifted on to university, but eventually he dropped out with music on his mind. He sang his passage over to Britain in 1970 on the SS Northern Star liner. Among a group of girls also on the ship was Melissa, who would become his wife and mother of their three children.

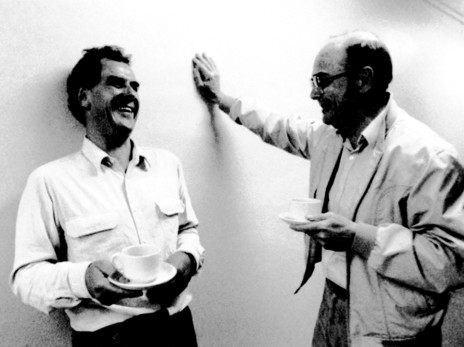

Soon after arriving in London, he began the grind of hawking his tapes around, doing whatever work he could while waiting. He was beginning to regret he’d forsaken America, the birthplace of jazz, for Britain, until a phone call out of the blue changed things abruptly. It was John Dankworth. Later Sir John, the first British jazz musician to be knighted, Dankworth needed someone to join his ensemble for a UK tour while Cleo Laine was away in Showboat. McNeill had been recommended and was offered the job over the phone. “I was sort of speechless and didn’t answer, because that was the top of the tree for me.”

Until then, McNeill’s mid-20s in London had been tough going. He shared a house with other musicians, sleeping in the hall, moving into a bedroom if someone was away and moving out again on their return. He worked as a cleaner to fill gaps between engagements. “One day I was cleaning someone’s beautiful oven. I had the radio on and there I was, singing on the BBC.”

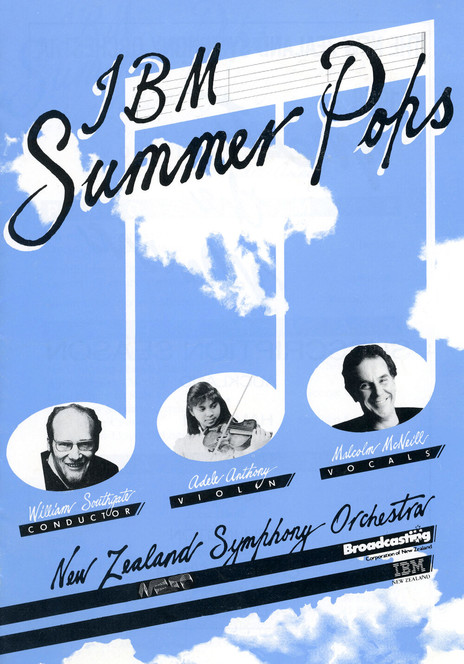

With the Dankworths he performed at Ronnie Scott’s in London and was a soloist with the BBC Orchestra, at New York’s Town Hall, and in Europe and Australia. There were also concerts in New Zealand with the NZSO, including wine festivals and well-attended summer pops, sometimes with the Dankworths’ daughter, Jacqui (“a fine singer and lovely young woman”).

“[Dankworth] had worked so closely with singers and knew where to give you room. It allowed you to spread your wings the best way you could. It was generous and musical, and he wanted your art.”

These years were musically fruitful for McNeill. He gained valuable experience with the Mike Sammes Singers, with them doing television, radio, shows at the London Palladium, and studio work, providing a wash of harmonic colour behind a diversity of performers, such as Barbra Streisand, Andy Williams, Bette Davis (“she was deeply moved by her own work”) and Gracie Fields (“a better, sweeter voice than you imagined”).

He sang in Ghana at the lavish wedding of the scion of an über-wealthy Lebanese family

There was also independent work, such as singing in a Gershwin concert in France with the Symphony of Nice, and an eccentric weekend’s gig in Accra, Ghana, to sing for the lavish wedding of the scion of an über-wealthy Lebanese family. Anything to escape the bleak London February, he thought, and he flew to Accra and the “extraordinary warmth and colour of Africa”.

His experiences there included seeing a baptismal service at the edge of the ocean and being the surprised recipient of a tinfoil twist of Ghanaian Gold that someone unseen pushed into his hand as he walked down the street. A large group of Ghanaian dancers and drummers was also entertaining at the wedding. “Their polyrhythms were like nothing I’d heard before – exuberant and joyous,” he says. The group was also exuberant behind the scenes, splattering the walls and floor of the green room in a wild food fight.

After half-a-dozen ultimately satisfying years in Britain, McNeill was jolted back into the realities of small-population life on his return to New Zealand, where the sounds of the day were showbands, saccharine pop, rock ’n’ roll, and country. He had to generate his own work, so he set to, writing and posting hundreds of letters of introduction, being promoter, publicist, and producer as well as performer. He and wife Melissa would organise the halls, shift the chairs, sell the interval wine and merchandise, and do the advertising. He and Biggles, his sheepdog, even wore sandwich boards around the city centre to advertise concerts, including in 1978 an anthology of Randy Newman songs, Rooting For Randy, which sold out in Christchurch, Wellington and Auckland.

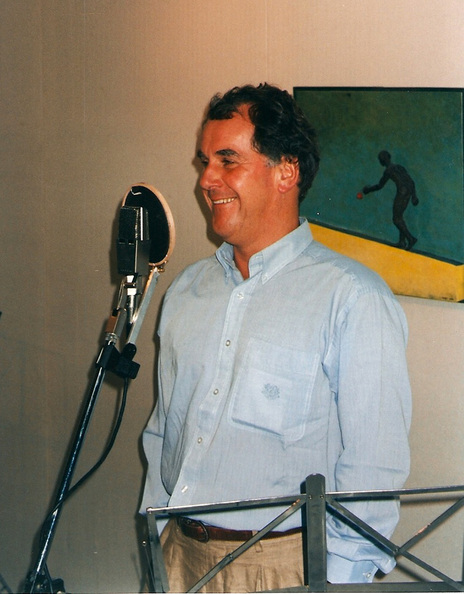

As he pursued the music this period led to more partnerships, creative work and an expanding fan base. He worked with pianist John Densem and had a long partnership on stage and in the studio with accompanist and arranger Dave Fraser. RNZ had been urging him to record, so he went into the studio with Fraser on piano, guitarists Kevin Watson and Martin Winch, Paul Dyne on bass, Frank Gibson Jr on drums, and Brian Smith on saxophone and flute. Dave Fraser co-produced this 1982 eponymous album with Kevin Oliff.

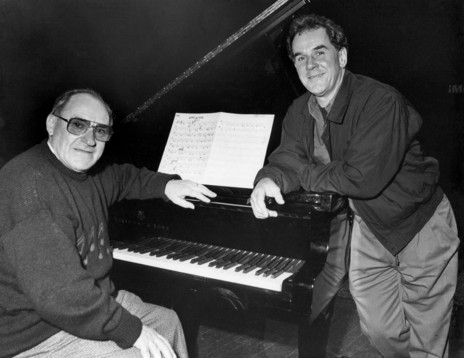

Much to his chagrin, there was never a recording with Doug Caldwell, however he continued appearing from time to time with Caldwell, who was still resident as an octogenarian at the Octagon, a bar-restaurant in a deconsecrated Victorian city church, until it was badly damaged in the quakes.

Singing in restaurants, “you can’t win against the knives and forks”

After returning from London, singing in restaurants became tired repetition (“I called myself the singing pot plant, because you can’t win against the knives and forks”). McNeill was keen to expand his range, get out of restaurants into the concert hall, and explore different genres, Elizabethan music being one. He realised as an experiential, largely self-taught singer that he needed tuition. A long-time friend and colleague in music – Christchurch-born, Wellington-based composer Dorothy Buchanan – provided the answer. She suggested he seek out singing teacher Mary Adams-Taylor, which he did. An Australian teaching at the University of Canterbury, Adams-Taylor had studied with Dame Joan Sutherland’s teacher in Sydney and later became opera singer Teddy Tahu Rhodes’s teacher.

“That wonderful relationship lasted 30, 35 years. Largely, we worked on one page of exercises, the same page, for that length of time. We never tried to change the idiom that I could do, but she helped me place my voice so there was no effort. We worked on Lieder … and I did the evangelist in [JS Bach’s] St. Matthew Passion, which is very difficult and high.”

Under Adams-Taylor he worked hard every day, often strapping his and Melissa’s firstborn to his chest (“wonderful for the baby”), and practising scales over and over. His work was diversifying incrementally, with performance as well as recording and producing. He also organised the vocal backing group for TVNZ’s long-running That’s Country series (1980–84), which featured national and international artists, and in the late 80s he produced and compered several sell-out themed shows – The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber, for example – for the Christchurch Symphony orchestra under conductor-arranger Wayne Senior. He appeared in some of these or selected the other singers to do so.

From his first studio album in 1982 McNeill went on to record eight more, choosing the material and working with various arrangers, from Dave Fraser to Julian Lee and others in Australia. He was also performing gigs from time to time with Christchurch pianist and singer Elizabeth Braggins, and co-produced her eponymous 1990 album with Nigel Stone, contributing lyrics on one track and duetting with her on ‘Hit That Jive, Jack’.

“She was lovely, so much fun … She’s a worker, she’s honourable and she’s damn good.”

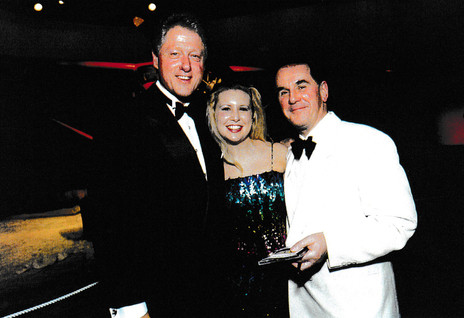

By the early 1990s, Malcolm McNeill’s name was widespread in jazz performance nationally and the plaudits kept accruing for him for setting the standard as, arguably, New Zealand’s best-known jazz vocalist. In 1990 he received a Commonwealth Medal for Services to Music and the Trust Bank Excellence Award, and when President Clinton was in Christchurch in 1999, McNeill organised the music for the presidential dinner, after which sax-playing Clinton commented, “That’s my kinda music. A terrific singer and a really great voice!”

Hearing McNeill sing, Bill Clinton said, “That’s my kinda music!”

Another project in the 90a had further underlined his musical status. This was Heart to Heart, the album of duets with Dame Kiri Te Kanawa for which he wrote the title track. It was recorded mostly in Auckland with orchestral tracks added later and Dame Kiri re-recording some vocals at Abbey Road Studios in London. Released in 1991, it features songs by various writers, among them Lennon-McCartney, Stephen Schwartz, Cleo Laine/Stanley Myers, and Boz Scaggs. McNeill enjoyed the process largely, but has some reservations.

“With Kiri, I would have liked it to be more fun, because she’s got a terrific sense of humour. Jeremy Lubbock [UK, 1931–2021], was the producer and wonderful arranger, but somewhat short on people skills. I think he wanted Kiri to be another Barbra Streisand, sort of, but she was already a big star in the classical world and didn’t need to.”

In later years, McNeill was the visiting tutor for jazz vocal studies at Massey University and he appeared in several Christchurch theatre productions: Jacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris for the Court Theatre; with columnist Helen Brown in a show they co-wrote, Words and Music; Kurt Weill’s The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny for the New Zealand Opera Company (director Raymond Hawthorne), and for the Repertory Theatre’s Twelfth Night in which he played Feste and composed new settings for Shakespeare’s songs. He worked for a time as an arts adviser and finally finished the degree he had started in the 60s, graduating in 2009 with a BA in art history.

Over his long career, there have been many highlights, among which include introducing the notion of adding jazz and contemporary music concerts to the NZSO’s repertoire.

“I remember first suggesting a concert of Gershwin and it seemed a far fetch. Ron Goodwin did the summer pops and that was that. The notion of including a jazz group in conjunction with the orchestra was a step too far for a long time. Eventually, I did 70 concerts with the NZSO, the best of them for me with the marvellous musical generosity of John Dankworth.”

McNeill lost most of his possessions in the Christchurch earthquakes, which effectively ended his career and coincided with his divorce. He spent the next decade or so travelling, living for some of the time in Thailand and spending long sojourns in Australia. He had sung with BLERTA from time to time in his late teens and one of the bandmembers in its character-filled musical soup was pianist and film composer, the late John Charles, who died in 2024. McNeill’s friendship with him and wife Judy stretched over 60 years, and it was to their place in Sydney he headed during recovery from a serious illness.

“I met John when I was about 18. He introduced me to Randy Newman songs, which we performed together over many years, both of us devoted to the musicality and wit of the songs, never tiring of them. Whenever I [went] to Sydney, John and I would retreat to the piano room for a session of Randy Newman and American songbook. He had a very loud piano, which I had to strain to sing above. Those sessions dwindled and died a few years ago, both of us ageing, but how fortunate to have had those years, all those wonderful songs.”

When McNeill looks back, some things are evident. To receive true recognition for achievement in this country can be difficult, especially for those in the finer arts. We have a good share of tall poppies here, as well as squadrons of naysayers ready with scythes.

“I think we’re cruel to our artists and regard the arts as a luxury. And the low-hanging fruit is the first to be cut. I grew up in the years of the six o’clock swill; I was not part of the macho culture, so I swam against the stream. I think that a lot of artists do, in various ways.”

As a New Zealand performer at the bottom of the world, with a small but dedicated following, McNeill did his utmost to introduce fresh material at every show, to maintain his own high standards and to deliver the same for his audiences. Fundamental have been the songs that speak to his heart, whether classics from the “great American Songbook”, musical theatre and art songs, or those from the jazz greats. “The songs are mythic for me,” he told Heath Lees of the NZ Herald in 1997. “They are intuitive ways of telling my story.”

And through both the joys and difficulties, one thing was always clear. “When I was trying to establish myself as a singer in London, I asked Cleo Laine how I could best further my career. Her reply was simple and straightforward: ‘Just keep doing it’. So I did; for 50 years I did … Financially, it wasn’t always a breeze, but I just knew I had to do it. Wild horses would not have stopped me.”