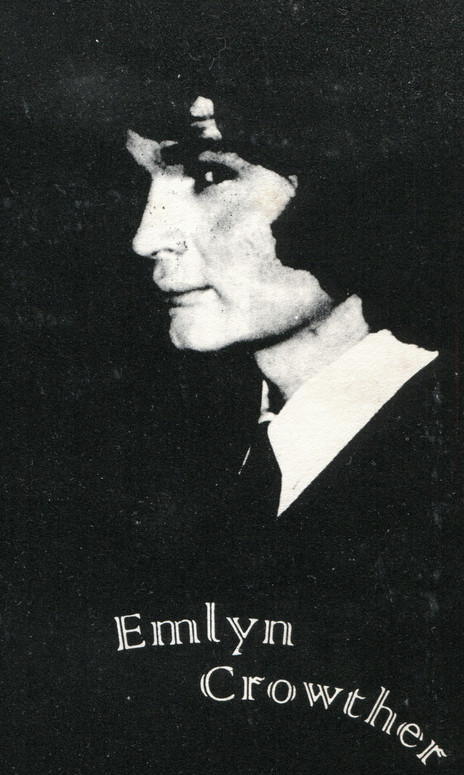

Paul Emlyn Crowther was born in 1949 and spent his early years in Dunedin. He joined Dunedin’s Saint Paul’s Cathedral choir as a boy soprano and was fascinated by the pipe organ in church.

“The huge pipe organ, I think that was what got me fascinated by sound, and from then on, I was always very interested in electronic organs and pipe organs.” On the way to choir practice, Paul started calling into the library, searching for more information on organs and electronics. “My bedtime reading was organ manuals.”

This fascination with sound and electronics led Paul to the Air Training Corps, aged 13. The members would meet each Friday night. Paul joined “mainly because I wanted to make crystal sets and pull old radios apart and study how they work.” The ATC band was also an attraction.

Disappointed to learn he couldn’t join the main ATC squad until he was 14, Paul was fortuitously advised by the bandmaster there was a way around the rule by joining up as a member of the training corps band. “I started on trumpet for a week, another guy took home [drum] sticks, but he soon asked if we could swap.”

“There was a chap above me called Graham Christie. He was a marvellous drummer – he was so inspiring. Later on, at school, he had a band called the Trendsetters. He had a Ludwig drumkit – it was all Beatles around at that time, so that was it! I had to have a drum kit! So I saved up all the money I had – I was 14 or 15 – and bought my kit one piece at a time.” (Beverly drums were a cheaper English kit you could buy one drum at a time, as you could afford, available at that time through Begg’s music shop in Dunedin).

Paul’s electronics obsession served him well.

Paul’s electronics obsession served him well. He left school as soon as he turned 15 and promptly gained employment with New Zealand Railways in communications, fixing telephones and working on the exchange. Meanwhile, the drum practice continued, and he celebrated his 16th birthday playing his first gig at a wedding in Balclutha with a three-piece dance band (piano, alto sax, and Paul on drums).

He stayed with the dance band for a year, playing waltzes, foxtrots, quick-steps, all the old-time dances still popular at the time. “After that, I was lucky enough to join a band called The Gentlemen, an excellent established pop band covering The Beatles, The Turtles, and The Hollies. At 17 years of age, I joined The Gentlemen and got my new sky-blue pearl Ludwig drum-kit. Everyone else at that time was getting Oyster Black kits, like Ringo’s.”

The year was 1967. The Gentlemen dressed sharply in Hardy Amies pin-striped suits, the look completed by two candy-apple pink Stratocasters and a pink Fender Precision bass. It was also the year that Paul first got his hands on a couple of Jansen organs and modified them to improve the sound.

In 1969 Paul took up an invitation to visit a friend who had moved to Auckland. He used his annual leave and travelled by train from Dunedin to Auckland – free travel was one of the perks of working with NZR.

On his arrival in Auckland, Paul’s first mission was to visit Begg’s music shop. There he bumped into Tony Walton, the drummer from Auckland blues band The Underdogs; Paul had met the band in Dunedin when they played there and often fixed equipment for them.

“Being a Tuesday I asked if there was anything on, and he said, well there is Embers nightclub in Chancery Lane. They were open seven nights a week. So I went to Embers, and it was folk night. I got talking to the singer Shelby Grant, there was a drum kit set up there, and he asked if I wanted to get up and have a play. So the first night in Auckland, I got to play the drums!”

Excited by the vibrant and busy Auckland music scene, he decided he wanted to follow the music. “I thought, I want to come and live here! There seemed to be so much going on musically.”

To stay in Auckland, he had a few things to sort out. Most importantly, how to make a living. “I applied for a temporary transfer with the Railways, and when my three-month term was nearly up, I wrote a cheeky letter asking for a permanent transfer to Auckland.”

The very day his application was approved, Paul received another work offer – an offer that was seemingly tailor-made and a dream job. Paul had previously taken a cassette recording of one of the Jansen organs he had modified into Sydney Eady’s music shop, and played it to Warwick Eady. After listening, Warwick asked if he could play the demo to his brother Bruce Eady. At that stage, Paul had no idea that Bruce was the owner-operator at Beverly Bruce & Goldie, the makers of Jansen products. “They made Jansen amplifiers! They offered me a job designing organs, they had already started a new one, and I just finished it off, I did all the circuit boards.”

The dream didn’t last too long; in 1970, along with a few other colleagues, he was made redundant. Paul found job security back at NZR, and although Jansen offered him his job back several times, he needed more incentive to take the risk to return to work for them.

Jansen offered Paul a job designing electric organs.

“Then Jansen got the agency for Lowrey organs. I knew a bit about those, having read all those manuals. I knew they were pretty good, and they were assembling them in New Zealand.”

Back then, because of import licensing restrictions, products from overseas had to be assembled in New Zealand to became local products. “The cabinets were all built here, so yes, I went back and worked for them, testing and repairing Lowry organs and still playing in bands in the meantime.”

By 1974, Crowther had developed strong friendships and enjoyed playing in bands around Auckland city. “I had been in a band called Orb with Alastair Riddell and Eddie Rayner [then known as Tony]. Eddie and I were good friends – I just loved his playing, and as he was also technically minded, we got on well. We had played together with Roger Skinner and The Motivation, and then we formed Orb.”

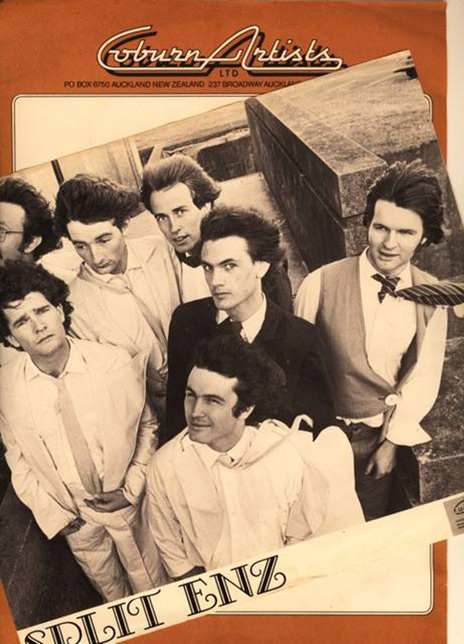

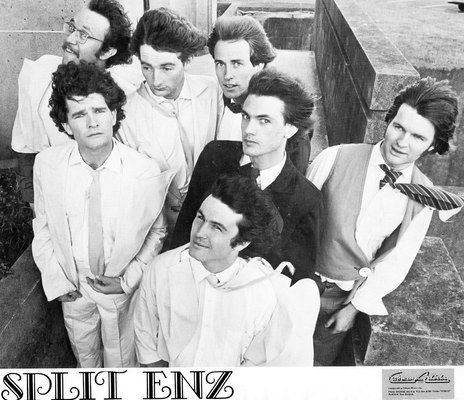

“We went to see Split Enz at the Peter Pan, which later became Mainstreet, and as soon as I saw the band I thought, ‘See you later Tony [Eddie]’, because I knew he just had to be in the band, it was obvious. Tim [Finn] was playing the piano, Geoff Chunn was playing drums, he had some nice ideas. The next time I saw them was a Buck A Head concert at His Majesty’s, and Eddie was playing with them.” Sunday nights at His Majesty’s were put on by Radio Hauraki. “I saw them playing and thought WOW! There was such a buzz about them – it was quite electric.”

Before long, Paul received a phone call from Eddie. “Geoff’s leaving, we are looking for a drummer, do you want to come and have a try?” “I thought, oh wow that would be fantastic. So I did, and when I got there it wasn’t like an audition where they were trying out a few drummers – we just had a play, and Tim said ‘okay, well we’ll practice next week’. So that is kind of how they did things.”

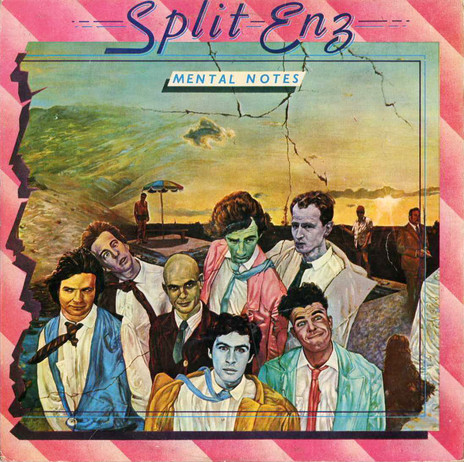

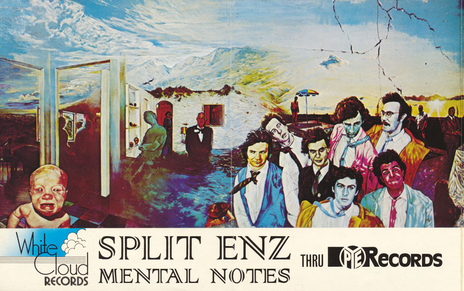

The next concert was to be in two weeks, so Paul quickly learned the songs – “basically everything on Mental Notes” – and drummed with Split Enz at another Buck A Head night, this time at the Mercury Theatre.

It was Roger Skinner who introduced Crowther and Rayner to Emerson, Lake & Palmer. They heard the synth played on ‘Lucky Man’ and, Crowther thought, “Well, I’ve got to make one of those!”

“I didn’t think, well I have to buy one, I just thought I had to make one. There was a lot of reading between the lines, and there was no technical data available on synthesisers – you couldn’t just Google it! I learned how they worked and sat and designed my own. It still isn’t finished, I’ve got things I need to add to it, but we used it in Split Enz [not the Mental Notes recording], and Dragon used it on their first album – Eddie used it live a lot. It wasn’t as tidy as you see it now.”

Paul built his own synthesiser, “probably the first synth with a keyboard in New Zealand.”

Paul built the synthesiser in 1972/73. “Mine was probably the first synth with a keyboard in New Zealand. I learned a lot by making that and tweaking it, and from the manufacturing notes, from the parts catalogues (Fairchild, etc). You could also get application notes, but the tricky thing was, I knew that the voltage controlled the keyboard output’s voltage, proportional to the note you are playing, and each time you move up by one octave, then that is a one-volt change. So it was one volt per octave, or 1/12th of a volt per semitone.

“The trick is: each time you move up one volt, the frequency of the oscillator has to double, so you have to have a thing called an exponential converter. It is two to the power of the control voltage – and then I had to work out how to do that! I found that out from a Motorola application note. I also had to make the envelope generator, with the attack time, and the decay time and sustain and release time. I had a recording called The Nonesuch Guide to Electronic Music (Beaver & Krause) which gave all the samples of the sounds – and descriptions of how modules on the synth worked – put out on an LP (I’ve still got it) and I just hung on to that stuff and just lived it, really immersed myself in it totally until I was able to build the thing!”

Crowther’s self-built synth is said to have been one of the more versatile synths around at the time. “I never got to make the filter, but there were two oscillators, each one had four waveforms – a sine wave, a sawtooth wave, a triangle wave, and a pulse wave. Mine had pulse with modulation, so it gave a nice fat sound, and the oscillators had everything in them, and you could combine the various waveforms as well, so it was pretty effective. It was a high note priority monophonic, and I had a glide control built into the keyboard. You could also vary the width of the keyboard so it could do one octave, or a few notes could cover an octave. It was pretty neat, and Eddie made use of all that, he figured it all out pretty quickly. I must get it going again.”

In 1975 Paul travelled to Australia, drumming with Split Enz, and it took some time to find the right shows to suit the band’s style and sound. Things started to change for them after a performance at a pub in Coogee Bay, when members of Skyhooks caught their set and mentioned them to Michael Gudinski. This lead to Split Enz landing the support slot for Roxy Music’s final show of their Australian tour, at Sydney’s Hordern Pavilion – the first time the New Zealand band got to play to a large appreciative audience.

Things were starting to happen for Split Enz. Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera showed interest in producing them. However, the timing wasn’t right, so they headed to Festival Studios and recorded Mental Notes with Dave Russell, former guitarist with Ray Columbus and the Invaders. He was, in Paul’s words, “acting as tour manager, mentor, and cool keeper” – as well as producing.

In Sydney, Roxy Music’s Phil Manzanera showed interest in producing Split Enz.

Paul’s description of that time is evocative and typical of young musicians living and breathing their art: “We were still living at the Squire Inn in Bondi Junction. They were exciting times, of course, we were totally broke, and I think our diet was pretty much bread with cottage cheese, and maybe a bit of jam on it or something. We had two weeks to record – after Mental Notes we got a deal with Island Records, and we were going to England to record and somehow that fell through.

“So we stayed in Australia and went to Perth for a while – we played to big audiences there. The first thing we did when we got to Perth was to support Frank Zappa at a big outdoor concert. We got a great reaction from that audience, played some more local shows, we had a marvellous time. We also supported Santana. Then it was back to Melbourne to play a farewell concert.”

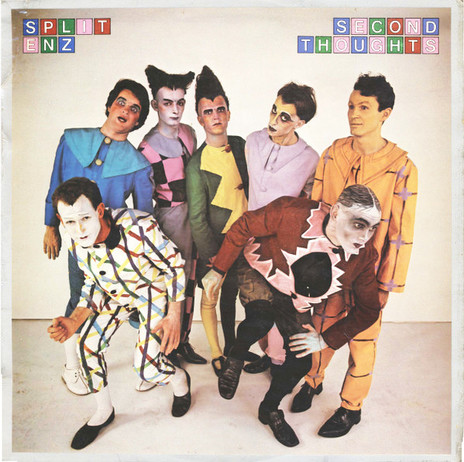

By now it was 1976 and, with the financial backing of Mushroom Records, Split Enz arrived in London. Due to a mix up in dates, they were stranded at the airport. After piling themselves and all of their gear into two cabs, and a stop off to check-in at the backpackers, they headed to Basing Street Studios in West London to start recording with Phil Manzanera producing. They re-recorded the songs from Mental Notes – and added ‘Late Last Night’ – for a new version of the album (released in Australasia as Second Thoughts).

After settling into a flat in London, Paul “still felt nine-to-five … I had always had a day job, you see.” He set up a small electronics workshop off to the side of the lounge in his flat, and in the mornings after dropping his wife Jo at work (Paul’s wife was working as a seamstress for British fashion designer Ossie Clark), he would go home and get to work on a few technical ideas he had been formulating. The Paul Crowther synth was not one of the six keyboards Eddie Rayner took to London, but Paul had another concept he wanted to pursue: creating his own fuzz pedal.

The pressure was on for Split Enz, with Mental Notes released in the UK in September 1976 to some positive reviews. Still, by November things were looking gloomy. A British winter was getting close, and the band had no airplay, no booking agent, and no shows in the pipeline.

In London, after leaving Split Enz, Paul started to make his first fuzz pedals.

Around this time, Paul left Split Enz: the decision was made for him and delivered by Mike Chunn. The news was crushing, but Paul Emlyn Crowther had so much to offer the world of music and audio. He started working at E-Zee Hire in Islington, repairing equipment. Before long he was making the fuzz pedals (then unnamed) for a few of the guitarists he met at the rehearsal space. “I played in a band called The Tidal Wave Band, and I made a pedal for the guitarist, so there are a couple of very early versions over in the UK.”

Jo and Paul returned to Auckland at the end of 1976, and soon Paul started working back at Jansen, testing and working on Lowry organs. A year later, Jansen put on a music showcase called EXPO 77, and it was there that one of the best sound techs in New Zealand began his career doing front-of-house sound.

In Auckland, Crowther embarked on another career, mixing live sound for bands. In 1979 he formed Livesound Ltd with two other Jansen employees, Paul John Carter and Russell Goodmanson. The company was dedicated to building and hiring out sound gear. With Auckland’s live scene booming, there was plenty of call for both the equipment, and proficient engineers to run it.

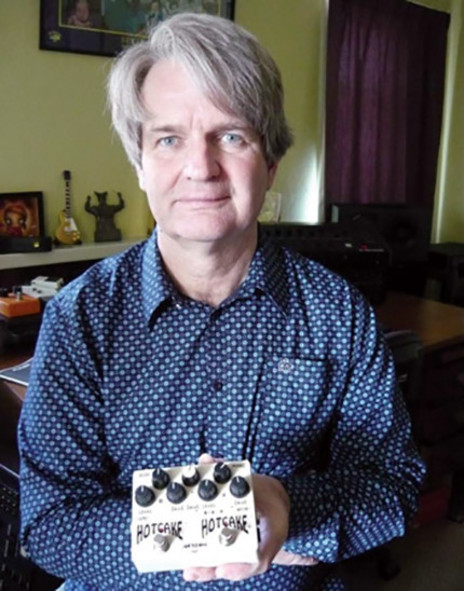

But Crowther also had a sideline, which emerged from his electronic tinkering. He began manufacturing his own guitar effects pedals, beginning with the best known: the Hotcake.

Read more: Paul Crowther’s Hotcake